Fantasia 2020, Part XXIV: Milocrorze – A Love Story

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

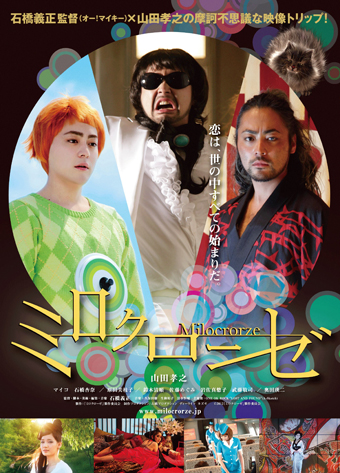

Thus Milocrorze – A Love Story (Mirokurôze, ミロクローゼ), a 2011 film written and directed by video and performance artist Yoshimasa Ishibashi. The winner of Fantasia’s awards for best director and most innovative feature film in the year it premiered, it was revived for this year’s festival, where I saw it for the first time. It is not like most other films, for both better and worse.

It begins by following a boy named Ovreneli Vreneligare who lives in a brightly-coloured eye-popping wonderland with a talking cat, and who falls in love with a woman named Milocrorze (Maiko). He hatches a plan to seduce her, it briefly works, and then things go astray. This leads to a dramatic shift in tone, as the movie leaves him to follow a TV huckster named Besson Kumagai claiming to give young men infallible relationship advice; the first of three roles played by Takayuki Yamada, Kumagai’s a 70’s lounge lizard who bursts into dance routines at odd moments. While dancing behind the wheel of a car, he blows into a group of people, and then we leave Kumagai and start following one of them.

Specifically, we follow a wandering samurai named Tamon (Yamada) who is seeking his lost true love. This becomes the longest part of the film, as we follow Tamon in and out of flashbacks (and through a tattoo studio featuring renowned director Seijun Suzuki in an extended cameo part) to a climactic fight sequence in a brothel and gambling den. Then we return to Ovreneli Vreneligare, now an adult played by Yamada, as he finds Milocrorze again.

You can look at the connections between these stories in a number of ways, but the first thing that has to be said is that the movie is consistently pleasurable to look at, in at least three different tones. Ovreneli Vreneligare’s candy-coloured dreamland is the most striking. The hyperactive modern world of Kumagai is a needed burst of energy. Then that’s followed by the melodramatic, weirdly-lit, deeply artificial world of Tamon, centred around its extended fight scene that drops in and out of slow and fast motion. There’s always something happening in this movie.

Whether it’s too much of a weird thing is another question. The film’s only 90 minutes long, but it’s difficult to relate to the characters as characters except in fleeting moments. They’re not so much cartoons as they are postmodern quotations of characters we’ve seen elsewhere. Two of the central figures express deep love for a woman, and indeed are driven by their love; but it’s difficult to take them seriously given the overwhelming irony of so much of the film. By comparison the straightforward aggressive sexuality and doctrine of dominance proclaimed by Kumagai the pick-up artist at least feels like a clearer object of mockery.

Whether it’s too much of a weird thing is another question. The film’s only 90 minutes long, but it’s difficult to relate to the characters as characters except in fleeting moments. They’re not so much cartoons as they are postmodern quotations of characters we’ve seen elsewhere. Two of the central figures express deep love for a woman, and indeed are driven by their love; but it’s difficult to take them seriously given the overwhelming irony of so much of the film. By comparison the straightforward aggressive sexuality and doctrine of dominance proclaimed by Kumagai the pick-up artist at least feels like a clearer object of mockery.

Narratively, the different sub-stories of the film barely relate. We wander from one to another, and it’s difficult to find any parallel or way in which one informs another. Kumagai’s section of the film can barely be said to be a story at all, more an extended showcase for the character and his perspective. Which of course may be the point.

The movie’s about love, and different characters experiencing love. My impression is it’s more specifically about the way one’s idea of love changes over time. Ovreneli Vreneligare begins with a child’s-eye view of highly romantic love that’s also game-like — build a nice enough house and you can attract the woman that you have fallen in love with at first sight. Besson Kumagai is an adolescent in a world of sex, in which what’s called love is predatory. Tamon’s an adult who has a more adult relationship, but is unable to let that relationship go. The fact he ends up in a brothel feels relevant, but in the end we return to Ovreneli Vreneligare as an older adult who must learn to let go of childish things.

At least, that’s how I read it. I’m not sure I’m wholly right, though the focus on love as a theme is clear. My interpretation is that there’s some cynicism here, and a certain amount of consolation. I think it’s about moving on from the idea of love as the be-all and end-all; moving past a juvenile ignorance of other people, past adolescent obsession with sex and competitiveness, even past the melodrama that puts a single relationship at the heart of one’s life.

At least, that’s how I read it. I’m not sure I’m wholly right, though the focus on love as a theme is clear. My interpretation is that there’s some cynicism here, and a certain amount of consolation. I think it’s about moving on from the idea of love as the be-all and end-all; moving past a juvenile ignorance of other people, past adolescent obsession with sex and competitiveness, even past the melodrama that puts a single relationship at the heart of one’s life.

The problem is, I could be wrong. I appreciate ambiguity, but I’m not sure that the way I’m connecting the dots is creating the shape the film has in mind. I’m not sure there’s enough coherence here beyond the weirdness, and come to that I’m not sure there’s enough depth under the surface of the weirdness. Yamada does a very good job crafting three different characters, two of which are superficially similar (in that Tamon and the adult Vreneligare are both driven by love affairs). But this isn’t really a character-centred film. His performance as Kumagai is more dynamic, and feels more central to the film as a result of its superficiality. It’s also faster, and overall I thought the pace of the film was slower than it could have been. The central fight scene in the Tamon sequence, for example, was shot nicely but went on for a long time with little variation in its visuals, so that it ultimately became repetitive in a way I’m not sure was intentional.

At least once a year in these reviews I feel it necessary to repeat that I’m a single critic from a specific culture (or set of overlapping cultures, if you like), and cannot know the ins and outs and references of other cultures. And can’t even know what I don’t know. I do know that, for example, I don’t know what the precise place of samurai melodramas is in Japanese culture, and how that passage of the film might be read. So it’s quite possible that the difficulties I have with the film would not be had by someone more knowledgeable about the movie’s background. But at least for a general North American audience this is a weird movie that moves through multiple weird tones, and the overall effect will be too weird, too ironic, or simply too distanced for a lot of viewers.

At least once a year in these reviews I feel it necessary to repeat that I’m a single critic from a specific culture (or set of overlapping cultures, if you like), and cannot know the ins and outs and references of other cultures. And can’t even know what I don’t know. I do know that, for example, I don’t know what the precise place of samurai melodramas is in Japanese culture, and how that passage of the film might be read. So it’s quite possible that the difficulties I have with the film would not be had by someone more knowledgeable about the movie’s background. But at least for a general North American audience this is a weird movie that moves through multiple weird tones, and the overall effect will be too weird, too ironic, or simply too distanced for a lot of viewers.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.