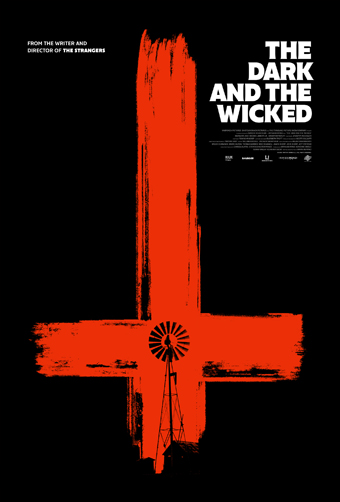

Fantasia 2020, Part XXIII: The Dark and the Wicked

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in Detention), but there were a lot of stories this year about people trapped in a structure, often with family, perhaps in a family home they’d returned to. Which strikes me as resonating with many situations I’ve heard about these past few months. The first movie I saw on Day 9 of the festival, The Block Island Sound, was an example of this trend. So was the second.

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in Detention), but there were a lot of stories this year about people trapped in a structure, often with family, perhaps in a family home they’d returned to. Which strikes me as resonating with many situations I’ve heard about these past few months. The first movie I saw on Day 9 of the festival, The Block Island Sound, was an example of this trend. So was the second.

The Dark and the Wicked was written and directed by Bryan Bertino, and set on an isolated farm in Texas (Bertino’s own family home, in fact) where an old man (Michael Zagst) is dying. His wife (Julie Oliver-Touchstone) tries to tend him, with the assistance of a visiting nurse (Lynn Andrews). But he’s going to die soon, and his adult children Louise (Marin Ireland) and Michael (Michael Abbott Jr.) have returned to be with him. Only to find some other supernatural force also lurks in the dark farm. Horrible things happen. An old priest (Xander Berkeley) comes by to offer assistance, but is rejected. Louise and Michael will have to find the power to deal with the darkness on their own. If they can even understand what they’re dealing with.

The first thing to understand about this movie is that it is purely a horror movie. It’s not horror mediated by some other aspect (like the dark-fantasy fairy-tale feel of Detention, or the family drama of The Block Island Sound). This is a movie about a place that has become the locus for clearly supernatural evil, and the story and look of the film follow from that. It’s drenched in lovely dark shadows. Natural vistas have an element of the sublime in the last light of the sun, but are empty of human life. We watch the characters flail about in this landscape, and know there will be no happy endings here.

There is in fact a good sense of balance to the mystery and the rules by which the supernatural evil operates. The dreamlike half-understood logic of the wickedness is a specific and effective horror on its own. We have, in fact, almost no idea what that logic is. But it does exist, and the characters’ refusal to try to understand it, their reluctance to accept anything supernatural is happening, is terrifying on its own. I would say that this feel fades a bit at the end, as the effect of the supernatural crescendos and the feel of rules that limit it fades. For much of the movie, though, there is a sense that the evil cannot simply wipe the characters out at any moment; that it can be fought, and indeed that it can be understood, but that the characters are choosing not to do either.

Along those lines, I will quibble that some of the actions — in particular the end of Michael’s arc — derive more from horror-movie logic than from credible human emotions. To an extent that’s fair, as this is so clearly a horror movie. But it’s a good enough horror movie, so true-to-life in its depiction of family ties and sibling bonds and emotions around the death of parents, that you wish it hadn’t given in so easily to convention.

Along those lines, I will quibble that some of the actions — in particular the end of Michael’s arc — derive more from horror-movie logic than from credible human emotions. To an extent that’s fair, as this is so clearly a horror movie. But it’s a good enough horror movie, so true-to-life in its depiction of family ties and sibling bonds and emotions around the death of parents, that you wish it hadn’t given in so easily to convention.

My main issue with the film, though, is the way that religion’s used. In a question-and-answer panel after the film Abbott observed that Bertino wanted to portray religion in the film not so much as a specific belief but a kind of context or communal structure which the parents failed to pass on to their children and which could have been useful to them (my paraphrase). I think I understand what he means, but it didn’t come out in the film. The story as presented felt to me as though it was arguing that religion was a necessary way to deal with the horrors of life, and was making that argument without supporting it in the story. (To be clear, I disagree with the idea, but think that stories that believe it can at least be interesting if they know what they’re doing; that’s not the case here.)

Mostly, this thematic concern’s separate from the presentation of the story, which is quite skillful. The pacing’s strong, and there are a lot of wonderful horrifying moments. The film’s able to find good reasons to regularly present disturbing images that aren’t just scenes of gore or maiming (there are some of those, too, and they’re also powerful and disturbing). Purely as a horror movie this is effective.

But you do wonder why Louise and Michael are slow to realise what’s going on around them and slow to turn to a possible solution. There needed to be more detail about their relationship to religion, I think, and why they might not accept it. This would be tricky, as part of the pleasure of the film is the strong sense of a sibling relationship between the two of them with all the unspoken history they share. But something more in some way was needed. At the very least, the logic behind the priest and his story and how it unfolds might have been clearer.

But you do wonder why Louise and Michael are slow to realise what’s going on around them and slow to turn to a possible solution. There needed to be more detail about their relationship to religion, I think, and why they might not accept it. This would be tricky, as part of the pleasure of the film is the strong sense of a sibling relationship between the two of them with all the unspoken history they share. But something more in some way was needed. At the very least, the logic behind the priest and his story and how it unfolds might have been clearer.

So The Dark and the Wicked is in the end cinematically very strong, and narratively very strong, but needs refining thematically. If it’s point were clearer I suspect the character beats would been clearer as well, and the horror would have been more coherent. As it is, the nature of the wickedness is oddly ambiguous — Louise and Michael put themselves in danger by returning to the farm, we’re told, but then once they’re there it seems the evil exists outside the farmhouse’s threshold. Is the evil external or internal? Is it the darkness inside the house and the despair it holds? Or is it a horror that needs to be invited inside? The movie’s worth thinking about in these terms, which is not nothing. But I can’t shake the sense that more clarity on these points would make it not just stronger thematically, but stronger as a story.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.