Hercules: Hero and Victim, Part 1

One of the greatest and probably the most famous hero in Greek mythology is Heracles, whom the Romans called Hercules, the name I first heard, thanks to certain films, when I was a kid. Some scholars call him by his original Greek name, others by the Roman version. Forgive me if I bounce back and forth between the two.

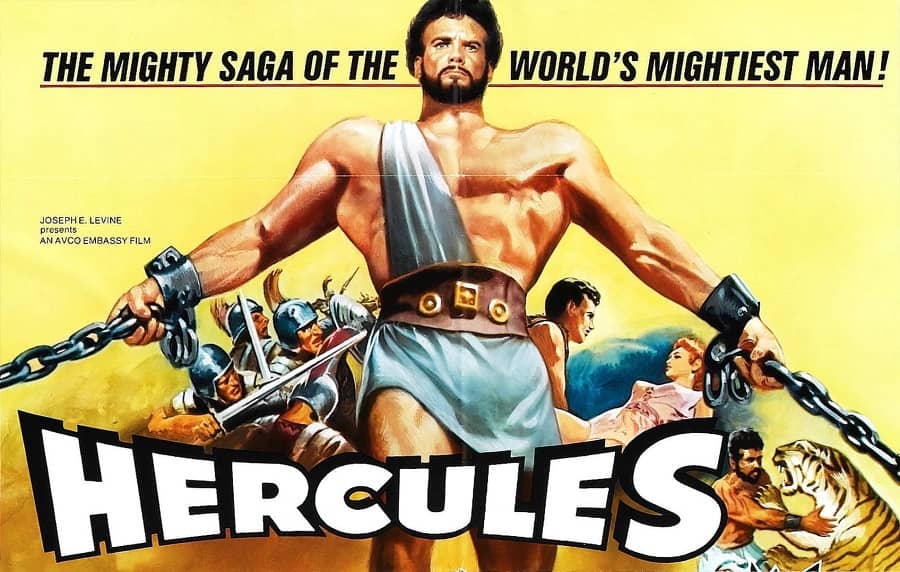

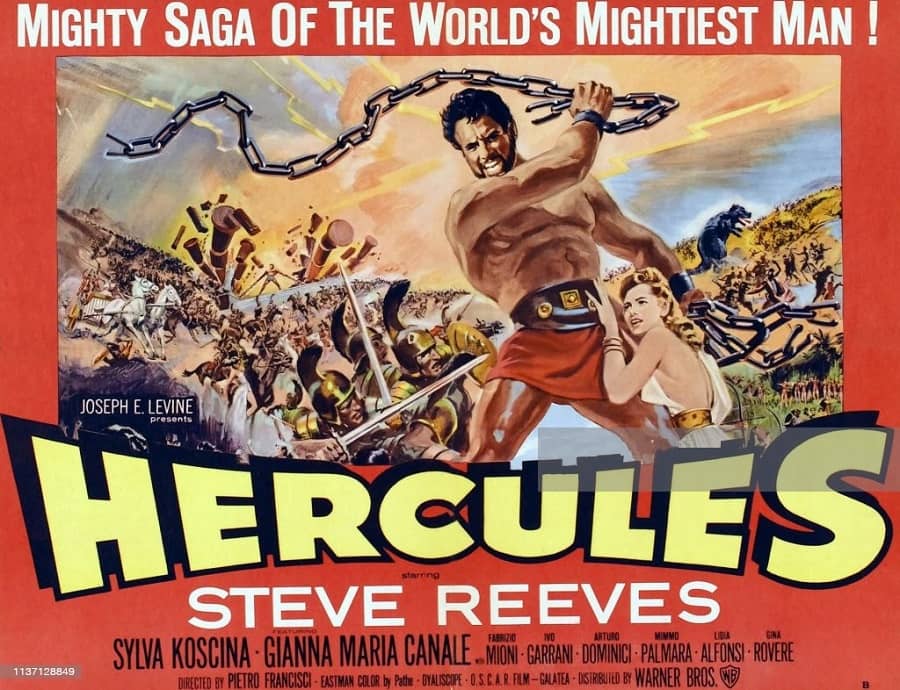

A while back, I decided to revisit three films which had a great impact on me when I was a kid, especially since I had the good fortune of seeing all three at the theater, during their first run: Hercules (1958) and Hercules Unchained (1959), both starring former body-builder and Mr. America, Steve Reeves; and Ray Harryhausen’s classic, Jason and the Argonauts (1963), where Hercules was played by Nigel Green. These led me to my grade school library, where I borrowed and devoured every book on Greek and Roman mythology I could find. In high school and afterwards, I discovered such books as Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, Bulfinch’s Mythology, by Thomas Bulfinch, God, Heroes and Men of Ancient Greece, by W.H.D. Rouse, as well as those by Norma Lorre Goodrich, Michael Grant, Carl Fischer, and Sir Richard Burton — not to forget Homer, Euripides, Ovid, and so many others too numerous to name.

Those books and those films, including the pepla films of the 1960s, had quite an effect on me. And lest I forgot, three other films also played a major part in my life: Harryhausen’s The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958), Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960), and Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949); incidentally, Steve Reeves was originally cast to play Samson, but then, as things in Hollywood often go, Victor Mature eventually secured the role.

There have been many novels about Hercules, and many captured the essence of this demigod, portrayed him as he is in myth and legend. As to all the films made about Hercules over the years, all deviated greatly from his story, as it was first set down by Ovid, and then later Euripides, Sophocles, Pindar, and Theocritus. Not one told his entire, dramatic tale, the complete myth from his birth to manhood, covering his Twelve Labors and all his trials, tribulations and tragedies. Pure fun and adventure, that’s what they mostly were, never showing much of the flawed human side of Hercules: he was usually portrayed as stalwart and heroic.

All that being said, I thought I’d take a different look at Hercules, a look at his character, his faults and virtues, his strengths and weaknesses.

Hercules (1958)

The Strongest Man on Earth

To the ancient Greeks, Hercules was the embodiment of what they most valued and admired: honor and courage, physical strength and beauty. He was the symbol of the Olympian Ideal. However, for all his god-like attributes and heroic stature, he was all too human.

Hercules was the strongest man in the world, and he possessed the supreme self-assurance that magnificent strength gives. To quote Edith Hamilton,

Throughout his life Hercules had this perfect confidence that no matter who was against him he could never be defeated, and facts bore him out. Whenever he fought someone the outcome was certain at the outset. Nothing of the natural world could ever best him. He could only be overcome by supernatural force.

He considered himself equal to the gods, and with good reason: he was the son of the Father of Gods — Zeus (called Jupiter by the Romans.) His mother was a mortal woman named Alcmene, Princess of Thebes. Hera, (called Juno by the Romans) was Zeus’ wife; she hated Hercules and was jealous of Alcmene. According to Thomas Bulfinch,

As Juno was always hostile to the offspring of her husband by mortal mothers, she declared war against Hercules from his birth.

Hera sent a pair of serpents to destroy the infant Hercules as he lay in his cradle, but the precocious babe strangled them with his own hands, thus foiling her plot.

Steve Reeves and Sylva Koscina in Hercules (1958)

Later, driven mad by Hera, Hercules slew his own children. To expiate the crime, Hercules was required to carry out ten labors set by his archenemy, Eurystheus, who had become King of Mycenae in Hercules’ place; both were of the House of Perseus, and had Hera not interfered, causing Eurystheus to be born prematurely, Hercules would have been king, instead. Now, if Hercules succeeded in the labors he’d been tasked to undertake, he would be purified of his sin and, as myth says, he would become a god, and be granted immortality.

According to the 1870 Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, edited by W. Smith, “Other traditions place Heracles’ madness at a later time, and relate the circumstances differently.” In some traditions there was only a divine reason for Hercules’ twelve labors:

Zeus, in his desire not to leave Heracles the victim of Hera’s jealousy, made her promise, that if Heracles executed twelve great works in the service of Eurystheus, he should become immortal.

In the play Heracles Mad, by Euripides, Hercules is driven to madness by Hera and kills his children after his ten labors. It was through her doing that King Eurystheus then added two more labors to the list.

Hercules Unchained (1959)

The Last of the Twelve Labors

Since most people are at least somewhat familiar with the Twelve Labors of Hercules, I won’t delve into each one. But as a reminder of these deeds he was commanded to perform, here are the first eleven; not all versions and writers give the labors in the same order. The Bibliotheca (2.5.1–2.5.12) gives the following order: Slay the Nemean Lion; Slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra; Capture the Golden Hind of Artemis; Capture the Erymanthian Boar; Clean the Augean Stables; Slay the Stymphalian Birds; Capture the Cretan Bull; Steal the Mares of Diomedes; Obtain the Girdle of Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons; Obtain the cattle of the monster Geryon; Steal the famous Golden Apples of the Hesperides.

Of these Twelve Labors, the last proved to be the ultimate challenge for this Son of Zeus, testing both his strength and his courage. King Eurystheus demanded that Hercules fetch for him Cerberus, the three-headed dog of Tartarus. This was a dangerous task, for Tartarus was the Land of the Dead and was ruled by the dark god, Hades. Not only did Hercules have to brave all the horrors of the Underworld, he had to risk his life battling that monstrous dog. Hades gave him permission to take Cerberus, provided he could so without the aid of weapons. As W.H.D. Rouse tells it,

Heracles therefore seized the dog with his hands, and crushed him tight until his spirit was tamed; then he carried him up into the world, and showed him to Eurystheus, after which he brought him back to remain as the watch-dog of Hades.

Not once, but twice Hercules had to walk the landscape of Death. Later in his life, he would do so again.

Having no intention to offend anyone of any Christian faith, and I hope I don’t, I will tell you this: I spent nine years in Catholic grade school, from kindergarten through all eight grades. Before I graduated, I spoke with one of my nuns about what I saw as parallels between Hercules and Christ. For instance, both were the sons of a god, and had been born to mortal women. Both were tutored by “scholars” — Christ by rabbis, Hercules by Chiron the Centaur — and each performed a set of miracles and labors. Both were also betrayed by one close to them: Judas, and by way of Nessus the Centaur, Hercules’ own wife, Deianira. Both Christ and Hercules died, and both were resurrected, the former ascending to Heaven, the latter to Mount Olympus. The nun found this interesting, and she suggested to me that many such myths, predating the Birth of Christ, were visions and prophecies of what was to come. I thought that idea was interesting.

Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

The Wisdom of Hercules

In his early youth Hercules was confused about his future and his destiny. When he was about 18 years old, he was approached by two women. The first was painted with make-up, wore gaudy jewels and was gaily attired. The other woman was stately and dignified, and her clothing was all of white. The flamboyant woman, familiar with the indecisiveness of youth and knowing of Hercules’ self-doubt, tempted him. “I invite you to follow me; you shall have the easiest and pleasantest life in the world, no hard work and no dangers; you shall eat, drink and be merry,” wrote W.H.D. Rouse. Other promises did she make the young hero, offering him a life free of care, if he but followed her. This woman said her name was Pleasure.

Then the noble-looking woman gave Hercules her advice, knowing something of his lineage and destiny.

I will not deceive you with promises of pleasant things, but I will tell you the truth. Nothing that is really good can be got without labor and hardship, for so the gods have ordained.

She told him if he wished the gods to serve him, he must first serve the gods; if he wished honor from his native land he must go forth and work for its benefit; the man who chooses the hard road and performs many noble deeds will attain everlasting glory and happiness. This woman was named Virtue.

Jason and the Argonauts

Though young, Hercules displayed a realistic insight into the nature of things, showing wisdom beyond his years. In the end he resolved to follow the path of Virtue, putting from his mind all craving for easy pleasure. “But his first task was to master himself before he could do great deeds with his own strength; for he had a violent temper.”

The son of Zeus, for all his awesome strength, often found it difficult to control his emotions. This was one labor in which he did not always triumph.

Next time, in Part 2, I’ll talk about the temper, tragedy and passing of Hercules. Thanks for joining me today. I appreciate it!

Joe Bonadonna is the author of the heroic fantasies Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser (winner of the 2017 Golden Book Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy); Mad Shadows II: Dorgo the Dowser and the Order of the Serpent; the space opera Three Against The Stars; the Sword-and-Planet space adventure, The MechMen of Canis-9; and the Sword & Sorcery adventure, Waters of Darkness, in collaboration with David C. Smith. With co-writer Erika M Szabo, he wrote Three Ghosts in a Black Pumpkin (winner of the 2017 Golden Books Judge’s Choice Award for Children’s Fantasy), and The Power of the Sapphire Wand. He also has stories appearing in: Azieran—Artifacts and Relics, GRIOTS 2: Sisters of the Spear, Heroika: Dragon Eaters, Poets in Hell, Doctors in Hell, Pirates in Hell, Lovers in Hell, and the upcoming Mystics in Hell; Sinbad: The New Voyages, Volume 4; and most recently, in collaboration with author Shebat Legion, he wrote Samuel Meant Well and the Little Black Cloud of the Apocalypse. In addition to his fiction, he has written a number of articles and book reviews for Black Gate online magazine.

Visit his Amazon Author or his Facebook Author’s page: Bonadonna’s Bookshelf

Joe Bonadonna has been a contributor to Black Gate since 2011. His most recent piece for us was a review of Hell Gate by Andrew P. Weston.

Steve Reeves is The Man.

Have you read Howard Waldrop’s “Twelve Tough Jobs”? A must for anyone interested in the Hercules legend.

John Miller – no, I have not read Waldrop’s book. Thanks for the tip!

John O’Neil – thank you once again for posting one of my articles – and for another great-looking layout!

Let me check myself on that — it should be A DOZEN TOUGH JOBS. Even though Twelve is more alliterative.

Epic review. I have not seen the Steve Reeve films. Usually, the Lou Ferrigno film is evoked for me (not that I remember much of it). Love your blend of movie/myth perspectives.

John Miller – yes, A Dozen Tough Jobs. I prefer Twelve Tough Jobs as a title. It has a better ring to it.

Seth Lindberg – The Steve Reeves Hercules are available, but as I said in part one – or maybe part 2 . . . I cannot find a good, clean/clear copy of Hercules. I have a crisp-looking copy of Hercules Unchained – but it was never remastered and put out in HD widescreen. I’ll have to check Reeves’ website. He made a great pirate film, too – Morgan the Pirate. But it’s rare: Dave Smith found a copy, dubbed in French!

I have a copy of Morgan the Pirate somewhere around here, in English. I can’t remember where I got it. THE BLUE ROSE is also quite good.

Yeah, I looked up the Waldrop story just to make sure that I got it right, and my eyes read A DOZEN TOUGH JOBS but somehow my brain turned it into TWELVE. It was nominated for a Nebula for best novella in 1990. Hard to believe it was that long ago.

John Miller – I’ll keep my search going. The Blue Rose – wasn’t that The Thief of Baghdad? Not a bad film at all, as I remember it. In fact, in a Sinbad story I wrote for one of Airship 27’s Sinbad volumes, the Blue Rose figures into the beginning and the climax of the story. I found the Waldrop book on Amazon – trade paperback, same with HUNTERS and SANDWORMS of Dune. But I have to make a trip to Office-Max soon, and there’s both a Barnes-Noble, and Half-Price Books right near there. So I’ll check those out before I order.

I seem to be having trouble with titles lately, but, yes, THIEF OF BAGHDAD. Blame that one on my memory. DOZEN TOUGH JOBS probably won’t be in a bookstore anymore. It was a Zeising original hardback. There are copies up on ABE very cheap, around $20, but not sure of the condition of those. On-line bookbuying has became pretty hit or miss nowadays.

John Miller – I have that problem a lot, but with more recent things. I remember the past, but recent events, forget about it. TOUGH JOBS hardcover from Amazon, quite expensive. Maybe “Almost Full-Price Books” will have a used copy. The search goes on!

Check out this link: https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&cm_sp=SearchF-_-home-_-Results&an=&tn=A+Dozen+Tough+Jobs&kn=&isbn=

John Miller – thanks for the link. I haven’t visited Abe Books in a long time!