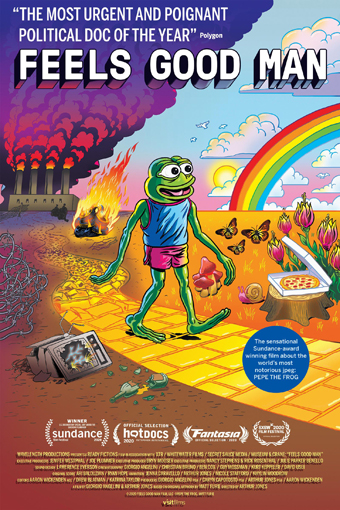

Fantasia 2020, Part XVII: Feels Good Man

I try to keep an eye on comics, but like many people my first exposure to Pepe the Frog was as a poorly-drawn meme spouting racism. I remember reading about Pepe’s comics origin, but the name of Matt Furie, the cartoonist who created him, remained a piece of trivia. As did his comic Boy’s Club, where the frog first appeared. Now there’s a documentary telling the whole story of Furie, Pepe, and Boy’s Club — a tale of politics, appropriation, and how art can be used in ways the artist could not imagine, for worse and for better.

I try to keep an eye on comics, but like many people my first exposure to Pepe the Frog was as a poorly-drawn meme spouting racism. I remember reading about Pepe’s comics origin, but the name of Matt Furie, the cartoonist who created him, remained a piece of trivia. As did his comic Boy’s Club, where the frog first appeared. Now there’s a documentary telling the whole story of Furie, Pepe, and Boy’s Club — a tale of politics, appropriation, and how art can be used in ways the artist could not imagine, for worse and for better.

Feels Good Man is the debut film from director Arthur Jones, and it’s solid work, starting with its structure. It begins with Furie, a soft-spoken man who discusses his early life and work up through the creation of Boy’s Club. The cast of the comic were four anthropomorphic animals loosely representing parts of himself, and Pepe the Frog was one of the less important of the four. Furie has no problem in saying that the book was full of lowbrow humour — Pepe’s name was chosen, he says, because it sounded a little like pee-pee.

One page would turn out to be more important than he could dream, with a sequence in which one of Pepe’s roommates accidentally walks in on the frog in the bathroom, and sees him pissing with his pants and underwear all the way down to his ankles. Later the roommate asks Pepe why he lowers his pants so far and Pepe says “Feels good man.” That catchphrase spread as a joke, first among Furie’s friends, and then beyond, and then to the internet in the form of a meme.

Here the film moves away from Furie to discuss memes, and the 4chan message board, and its culture of offensiveness and self-loathing, and how Pepe fit into all of that. Much of the film from this point on shows Pepe and his image mutating further and further, joined in memes with characters like Wojak, co-opted by the racists of the alt-right, used by nihilists to push the election of Donald Trump — used even by Trump himself. Pepe was listed as a symbol of hate by the Anti-Defamation League, despite the best efforts of Furie to regain control of the image. Internet tech-bros paid ridiculous sums for ‘rare Pepes’ on the blockchain. Then, out of nowhere, an improbably happy ending, as pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong come across the frog online and use him as a symbol of their movement.

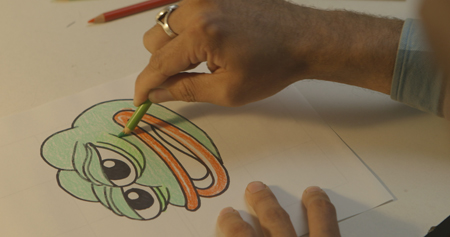

Furie remains a constant throughout the film, and he makes a satisfying if soft-spoken protagonist. You have to feel sympathy for him — his artistic creation was used without his permission in a way he abhorred but was powerless to stop. We see that Furie’s more than Pepe, and get a sense of his other work; we also see the difference between the Pepe he draws and the Pepe redrawn in memes, how Furie’s warm, thick ink line is more inviting, how his graphic sensibility recalls underground cartoonists and through them classic animation.

Feels Good Man is mostly not about comics, though, for better or worse. While it might have been interesting to compare Furie’s situation to the struggles of previous cartoonists — Crumb and “Keep On Trucking” and Fritz the Cat, Steve Gerber and Howard the Duck, Bill Watterson and the pissing Calvin, the saga of Skippy and Skippy Peanut Butter — there’s an awful lot to get through to explain Pepe over the past few years. There’s a lot about the internet, about memes, about message board culture, about American politics, and about how all these things interrelate.

Feels Good Man is mostly not about comics, though, for better or worse. While it might have been interesting to compare Furie’s situation to the struggles of previous cartoonists — Crumb and “Keep On Trucking” and Fritz the Cat, Steve Gerber and Howard the Duck, Bill Watterson and the pissing Calvin, the saga of Skippy and Skippy Peanut Butter — there’s an awful lot to get through to explain Pepe over the past few years. There’s a lot about the internet, about memes, about message board culture, about American politics, and about how all these things interrelate.

This is not easy to do, always, especially when it comes to politics and the nihilism of the Trump supporters who weaponised Pepe in the last American presidential election: young people, mostly men, who wanted to see Trump win just because he wasn’t supposed to. Pepe was used here just as, the film shows us, he or his meme version was used on 4chan as a defense against the normies. Pepe became an in-group signifier, and the in-group grew more and more radical.

Feels Good Man is less a comics documentary, then, than it is an examination of online spaces and a documentation of just how weird American politics became in the second decade of this century. An occultist, John Michael Greer, discusses the occult power of Pepe as a sigil and seems relatively logical. In fairness, Greer’s an intelligent man; his New Encyclopedia of Occultism is a useful reference work (though dating as it does from 2003 it’s sadly deficient in its examination of cartoon frog memes). Here, he gives a solid analysis of how the monosyllable ‘kek’ became associated with Pepe, and its various other meanings, and how it was linked to the Egyptian deity Kek, and how by extension Pepe became the god of memes. I invite you to consider the previous sentence, and ponder the nature of political iconography in the internet age.

Feels Good Man is less a comics documentary, then, than it is an examination of online spaces and a documentation of just how weird American politics became in the second decade of this century. An occultist, John Michael Greer, discusses the occult power of Pepe as a sigil and seems relatively logical. In fairness, Greer’s an intelligent man; his New Encyclopedia of Occultism is a useful reference work (though dating as it does from 2003 it’s sadly deficient in its examination of cartoon frog memes). Here, he gives a solid analysis of how the monosyllable ‘kek’ became associated with Pepe, and its various other meanings, and how it was linked to the Egyptian deity Kek, and how by extension Pepe became the god of memes. I invite you to consider the previous sentence, and ponder the nature of political iconography in the internet age.

The point the movie makes is that there’s an unpredictability to the way the nebulous crowds of the internet will use and transform a meme. Hillary Clinton tried to undercut the pro-Trump Pepe memes with an ‘explainer,’ which couldn’t help but be ludicrous. Furie tried to kill Pepe off, to take him back by launching a ‘#SavePepe’ campaign recasting him as a force for good, and finally to assert control of his creation by suing alt-right figures using the frog for their own gain. Furie’s story is a good way to tie all this together, and the ending feels logical: the inherent randomness of the internet acting for good, as pro-democracy protesters use the image for their own struggles. “I believe that one day his frowning face will smile,” one of them says, and you hope this is so.

Feels Good Man is a story about art and its effects. No artist can control how their art affects the world, and this is one of the most extreme examples of that fact. Whatever meaning Pepe originally had was hollowed out, the image reduced to a kind of shell repurposed by others. The documentary’s disturbing and engaging, but I wonder if it’s not also a warning. If the memeification of Pepe followed a path specific to what the internet looked like at that exact moment a few years ago, how different is the technology now? Will other creators see their work taken from them in the same way? It’s one thing to understand what happened to Pepe. I wish there were steps to take if this sort of thing happens again, something beyond merely hoping that what’s used for vicious purposes also ends up being used for the good.

Feels Good Man is a story about art and its effects. No artist can control how their art affects the world, and this is one of the most extreme examples of that fact. Whatever meaning Pepe originally had was hollowed out, the image reduced to a kind of shell repurposed by others. The documentary’s disturbing and engaging, but I wonder if it’s not also a warning. If the memeification of Pepe followed a path specific to what the internet looked like at that exact moment a few years ago, how different is the technology now? Will other creators see their work taken from them in the same way? It’s one thing to understand what happened to Pepe. I wish there were steps to take if this sort of thing happens again, something beyond merely hoping that what’s used for vicious purposes also ends up being used for the good.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.