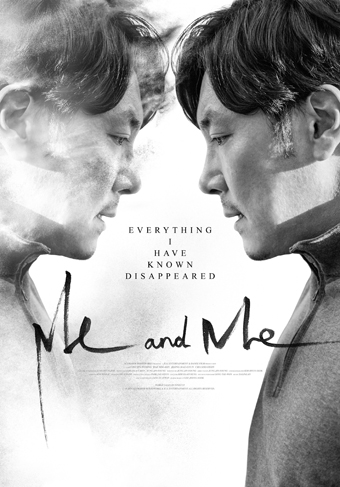

Fantasia 2020, Part XVI: Me And Me

One of the genuinely wonderful things about covering a film festival is occasionally getting to be among the first audiences for a movie trying something new. That is, being an early viewer of a movie that does things unlike other movies, and getting to make one’s own mind up on whether those things work. Movies at a festival have often not had a critical consensus formed around them, and have not yet been defined by other writers or had their influences mapped out. You as the viewer are alone with the thing, almost contextless, in a way that’s rare these days.

One of the genuinely wonderful things about covering a film festival is occasionally getting to be among the first audiences for a movie trying something new. That is, being an early viewer of a movie that does things unlike other movies, and getting to make one’s own mind up on whether those things work. Movies at a festival have often not had a critical consensus formed around them, and have not yet been defined by other writers or had their influences mapped out. You as the viewer are alone with the thing, almost contextless, in a way that’s rare these days.

I feel this most vividly with movies I don’t fully understand. Not movies I think are bad, or movies I’m wholly sure are good, but movies into which I must feel my way slowly even after seeing them. Like or dislike a blockbuster tentpole, a Marvel film or Star Wars film, I understand what they’re trying to do and how. It’s when watching a movie that gives me clues but baffles me, a movie that clearly is animated by wisdom and intelligence but which I can’t quite assemble into a coherent whole, that I’m aware of being among the first to try to articulate what I’m seeing.

To say all this is to give an idea of the effect of Me And Me (Sarajin Sigan, 사라진 시간). It’s the debut feature from Jung Jin-young, who also wrote the picture. Jung’s a veteran actor, and he’s clearly thought through what he wants to do with his movie. At one viewing, I will not claim to fully understand it. But then, it’s fair to say that understanding is not always necessary to appreciate art.

The movie starts in a small village in Korea, with a young teacher, Soo-hyuk (Bae Soo-bin), and his wife Yi-young (Cha Su-yeon). It soon becomes clear that Yi-young has a problem: at nightfall she’s possessed by a spirit of a dead person. Not necessarily the same dead person every night, either. News of this spreads through the village, and leads to tragedy, which brings a police detective, Hyung-gu (Cho Jin-woong) to town. (Cho’s also the star of Jesters: The Game Changers, an example of a film that does what it does in a much more linear manner.)

With Hyung-gu’s entrance on the scene the story shifts to follow him as he investigates the rustics of the town. By about the middle of the film all the mysteries seem to be cleared up, and we at least think we know what’s happened. Then there’s a swerve. Without wanting to give away too much, it may be said that Hyung-gu wakes up to a very different life. As he, and we, try to work out what’s happened, unexpected connections come to light; the movie does some odd structural things; finally it ends, with the plot apparently not resolved as we might have looked for, but with a circularity (and a shot repeated from the opening) that implies things have worked their way around to a slightly better state.

Jung told a Forbes interviewer that “I deliberately eliminated detailed explanations, which a lot of commercial films normally have, but planted the clues here and there, which I intended to help the audience think for themselves. … Audiences have no choice but to think for themselves after watching this movie. Thus, diverse levels of interpretations could be made and they’re all correct interpretations. What I’ve wanted as a director and a writer was not one fixed correct answer to this story, but to give people time to seek their own answers.” And: “In zen dialogue, there is no such thing as an answer. … If a questioner and a respondent have some spiritual and emotional communication, it makes both question and answer the proper ones. However, if there is no such communication, the question becomes meaningless, as well as the following answer.”

Jung told a Forbes interviewer that “I deliberately eliminated detailed explanations, which a lot of commercial films normally have, but planted the clues here and there, which I intended to help the audience think for themselves. … Audiences have no choice but to think for themselves after watching this movie. Thus, diverse levels of interpretations could be made and they’re all correct interpretations. What I’ve wanted as a director and a writer was not one fixed correct answer to this story, but to give people time to seek their own answers.” And: “In zen dialogue, there is no such thing as an answer. … If a questioner and a respondent have some spiritual and emotional communication, it makes both question and answer the proper ones. However, if there is no such communication, the question becomes meaningless, as well as the following answer.”

For me, the film succeeds in leading me to seek answers. That is, while I’m confused by some aspects of it, I believe there is meaning to it, and that it is a focussed artistic exploration of certain themes, especially that of identity. (From the interview again: “How different is the person I think I am and the person others think I am? Who is the real me among them? What is the existential essence of myself? These are the questions I’ve wanted to ask.”) I would also say this is a movie that requires a lot from its audience, in terms of active engagement, maybe more than the first half or so would suggest.

There’s nothing superficially ‘difficult’ about the film. It looks nice, with an understated realism. The acting’s strong; even when facing fantastic situations, the actors give their characters a warm humanity. Cho goes through a long journey as Hyung-gu, with some wrenching emotional sequences of fear, grief, and anger, as well as learning to drop a certain wariness to accept human communication. You understand and feel all these things as he does. But the first half of the film seems to be setting up a different shape to its second half; and seems to promise a more obvious narrative, with a more closed shape, than we actually get.

This is not really a criticism. By the end of the movie we can look back and see themes and symbols have worked their way into the narrative in ways we did not expect. Families and family bonds of different shapes are investigated in different ways. Fire and burning things recur. Keys are mentioned at significant moments; so are deer.

This is not really a criticism. By the end of the movie we can look back and see themes and symbols have worked their way into the narrative in ways we did not expect. Families and family bonds of different shapes are investigated in different ways. Fire and burning things recur. Keys are mentioned at significant moments; so are deer.

But narratively the film seems to move through different stories, leaving old ones behind like a snake’s shed skins. The last scenes in particular, set at a spa and temple, suggest a new shape for the film even as characters return from a previous section. Is there a Buddhist implication? Does the film hint at some unity of spirit under an apparent individuality?

I don’t know. But it is certainly focussed on dreams, and the other world that comes as we sleep. We are told dreams are “like incinerating the unneeded trash of our memory” — fire again. And yet the movie’s naturalistic, as much as it can be when dealing with the subjects and plot points it is. The symbols are worked naturalistically into the story.

It’s a film that moves between comedy and tragedy, not so much changing tones as using each as undertones for the other. As we watch comically bumbling villagers we know how severe their actions can be. As we watch Cho mourn things he’s lost we’re also struck by the absurdity of his situation. Me And Me is uncommon in its ability to balance laughter and tears so that one predominates but the other’s present, and so instill in a viewer the knowledge that soon it will be the other way around.

This is not a movie I claim to wholly understand on more than the simplest level. That happens from time to time. My rule of thumb for judging movies like that is this: am I interested enough by this movie to watch it again in order to understand it better? For Me And Me the answer is yes, but I’d have to be in a fairly specific frame of mind. It’s not the fastest movie, and for much of its running time it presents a kind of naturalism that does not personally interest me. But there’s enough of the fantastic in it, and enough of the gnomic, that I can’t help but be intrigued. This is not a movie for every day. But it’s a movie that has much in it worth pondering.

This is not a movie I claim to wholly understand on more than the simplest level. That happens from time to time. My rule of thumb for judging movies like that is this: am I interested enough by this movie to watch it again in order to understand it better? For Me And Me the answer is yes, but I’d have to be in a fairly specific frame of mind. It’s not the fastest movie, and for much of its running time it presents a kind of naturalism that does not personally interest me. But there’s enough of the fantastic in it, and enough of the gnomic, that I can’t help but be intrigued. This is not a movie for every day. But it’s a movie that has much in it worth pondering.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.