Recomplicated Realities: Philip K. Dick’s Eye In the Sky and Two Others

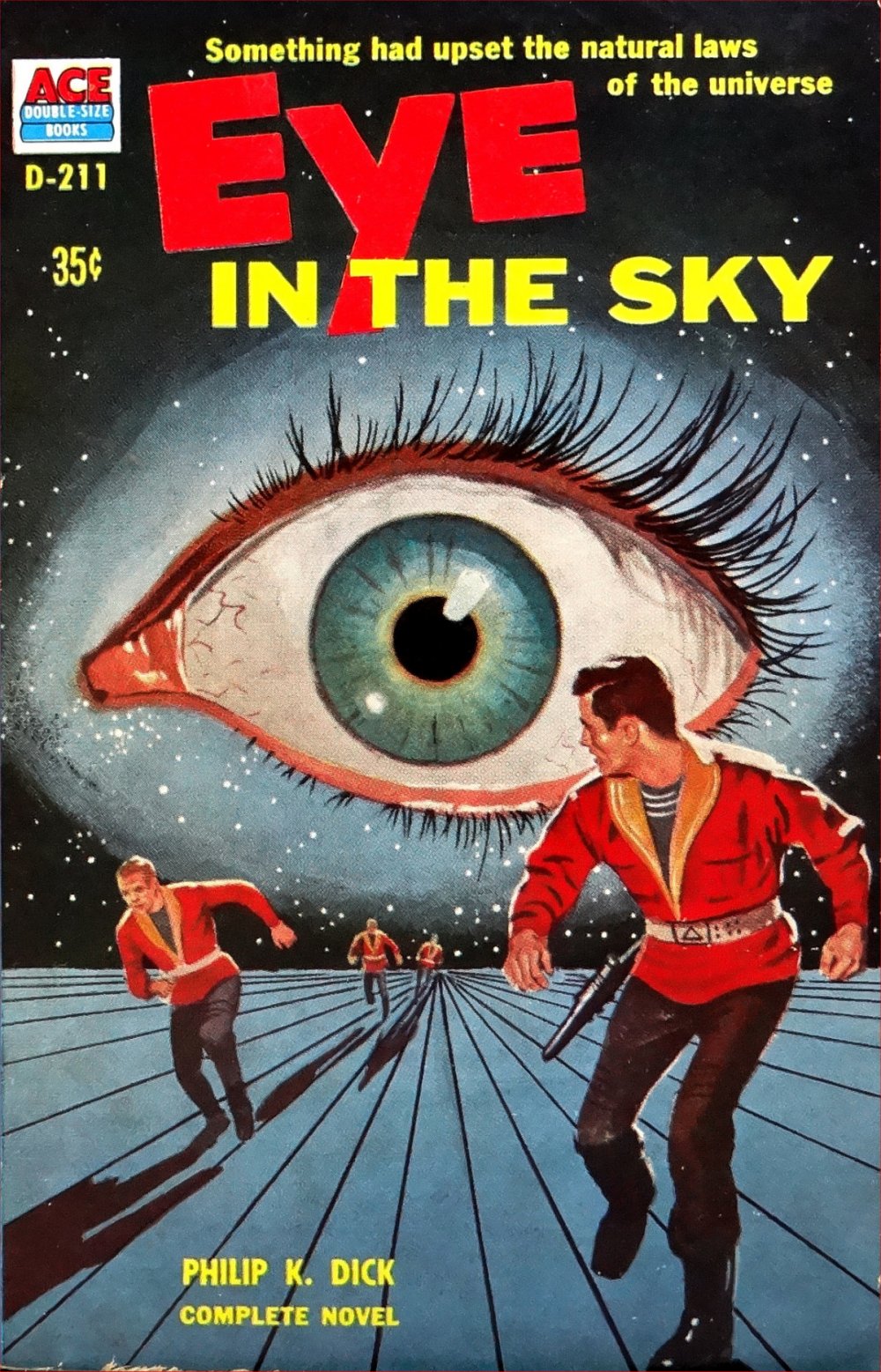

Eye in the Sky by Philip K. Dick; First Edition: Ace, 1957.

Cover art likely Ed Valigursky. (Click to enlarge)

Eye in the Sky

by Philip K. Dick

Ace (255 pages, $.35, paperback, 1957)

Cover art (likely) Ed Valigursky

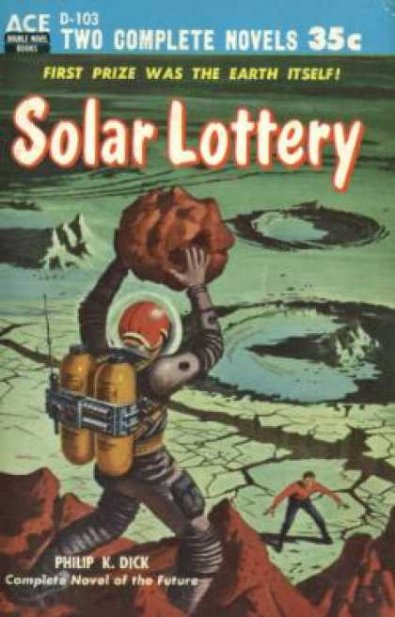

Solar Lottery

by Philip K. Dick

Ace (188 pages, $.35, paperback, 1955)

Cover art unidentified

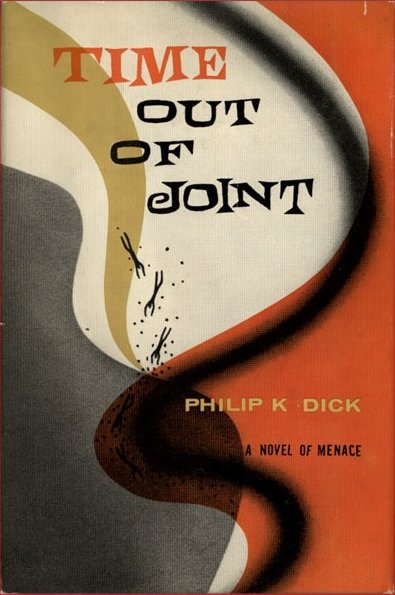

Time Out of Joint

by Philip K. Dick

Lippincott (221 pages, $3.50, paperback, 1959)

Cover art Arthur Hawkins

I confess I’ve never warmed to Philip K. Dick. His stories can be dazzling in their ways, in their reversals of premises, in their recursiveness, in their variations on overturning the assumptions we make about the nature of reality. It’s been a while since I’ve read much PKD, but I read three of the early novels in the past two weeks: his first, Solar Lottery (1955); his fourth-published, Eye in the Sky (1957), and his seventh-published, Time Out of Joint (1959). And my impression from these three early novels is that despite PKD’s characteristic virtues just mentioned, his characters are rarely sympathetic, his pacing and plotting are uneven to the point of being haphazard, and his science-fictional components are standard SF furniture at best, comic book nonsense at worst. And these are three of his best early novels — the best three, apparently, until he published The Man in the High Castle in 1962.

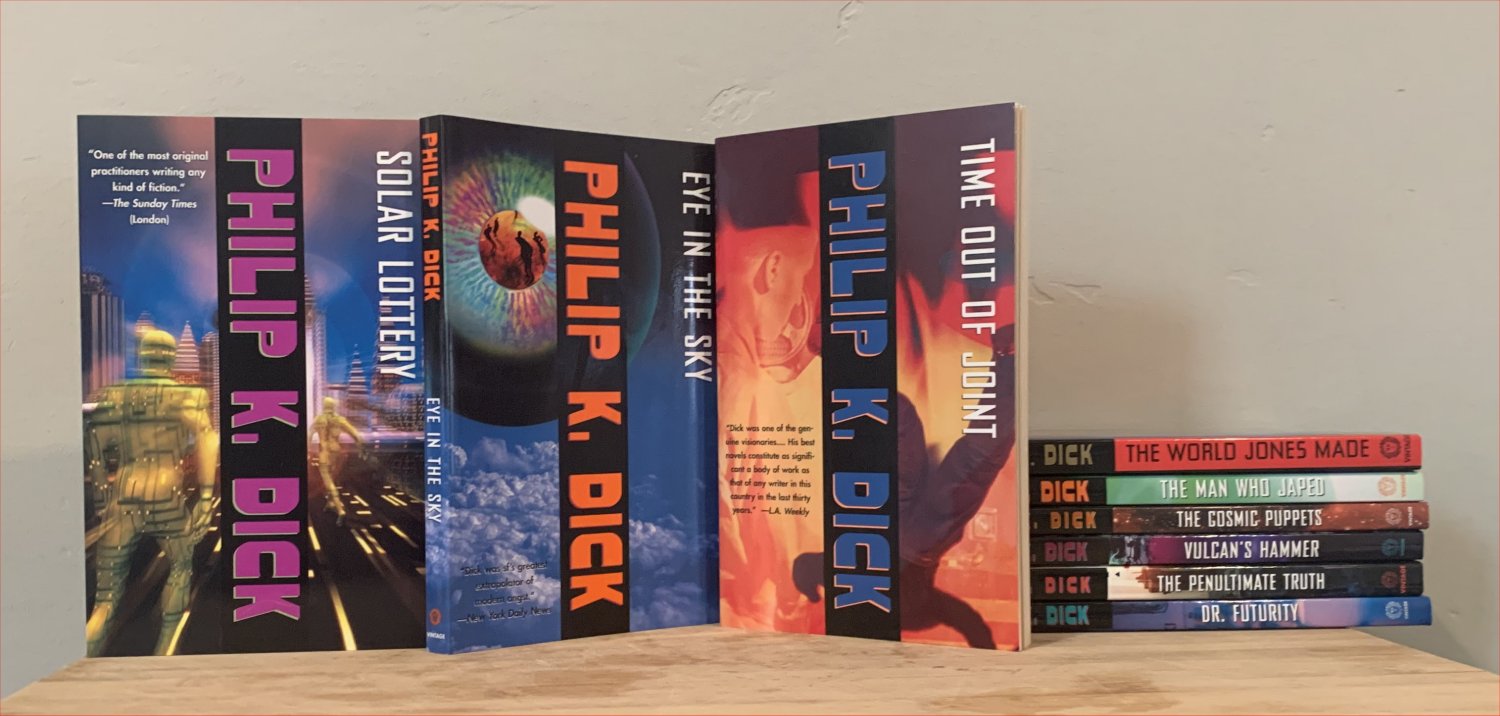

And herein is an issue for the casual PKD reader. Where to start? It’s commendable that publishers have returned his work to print over the past couple decades, but for Vintage, as it did in the early 2000s, to release 34 of Dick’s SF novels in matching covers implied that they were all of roughly even quality, and one distinction of PKD compared to other popular writers of the ‘50s and ‘60s is that his work was highly erratic. (In fact, I did read two of the early novels when Vintage reissued them back then, The Man Who Japed and The World Jones Made, and read no further.) More recently, Mariner issued the same batch in 2011 and 2012, again in matching covers.

Vintage Books editions of several PKD novels, including

Solar Lottery (2003), Eye in the Sky (2003), and Time Out of Joint (2002)

All cover designs Heidi North (Click to enlarge)

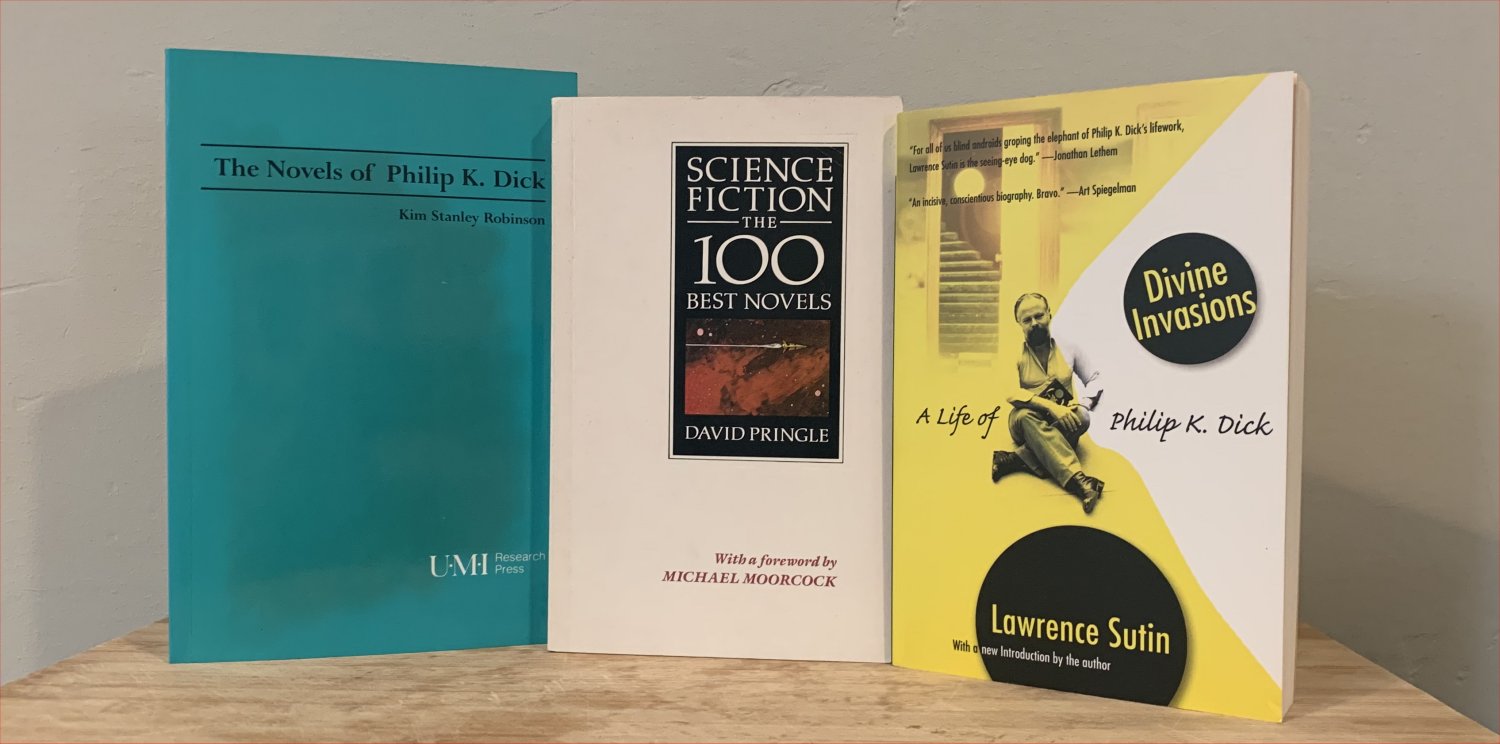

Fortunately I’ve accumulated a dozen or so nonfiction books by or about PKD over the years, and two in particular were helpful in orienting me to where to start this time. (Not that I’m relying on their analyses or insights; I’ve tried to formulate my own reactions.) These are Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Novels of Philip K. Dick (which began as a university dissertation!), and Lawrence Sutin’s biography Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. The latter in particular rates all of PKDs books, including non-SF novels and short story collections, on a scale of 1 to 10. Thus I chose the three I did, which Sutin rates 5, 7, and 7 respectively, while Japed rates 2 and Jones 4. (At the extremes, Sutin rates Dr. Futurity and Vulcan’s Hammer, both from 1960, 1, while four titles are ranked 10: The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965), Ubik (1969), The Best of Philip K. Dick (1977), and VALIS (1981).)

There are also the six PKD titles chosen by David Pringle to be among his Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels (1985, compiled here): Time Out of Joint, The Man In the High Castle, Martian Time-Slip (1964), Dr. Bloodmoney (1965), The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968).

Nonfiction about Philip K. Dick, all or in part:

The Novels of Philip K. Dick, Kim Stanley Robinson (UMI Research Press, 1984)

Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels, David Pringle (Xanadu, 1985)

Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick, Lawrence Sutin (Carroll & Graf, 2005)

(Click to enlarge)

I came away preferring Eye in the Sky slightly to Time Out of Joint, and didn’t care much for Solar Lottery. I’ll discuss Eye in detail, and then mention the other two more briefly.

Gist

An accident at a nuclear facility leaves a tour guide and seven tourists in a heap on the floor. As they wake they find themselves inhabiting the private realities of one after another of the seven, before they manage to escape back into the real world.

Take

This is a good example of PKD’s recurring theme of “what is real?”, and the book has a lot of fun extrapolating the details of a world as imagined by a religious fanatic, a prim lady, a paranoid shopkeeper, and so on, with an ending that unexpectedly wraps things up nicely.

Summary

Page references are to the Vintage edition.

Chapter 1:

- We’re told right away about an accident at the Belmont Bevatron on Oct 2 1959, causing 8 people on a platform to plunge to a floor 60 feet below. (Belmont is a small city south of San Francisco, on the peninsula.)

- Then we back up in time just a bit to Jack Hamilton, who works in a missile research lab and has a security clearance. He and his wife Marsha are summoned by his boss, Colonel T.E. Edwards, to a meeting with security chief McFeyffe, who expresses concern that Marsha has been attending certain meetings, reading certain magazines, that suggest communist sympathies. Hamilton defends her: she reads plenty of other things too! But he can’t disprove their suspicions; and so, because of security clearance issues, Hamilton is fired.

Chapter 2

- Nevertheless, Hamilton and his wife are eager to visit the nearby Bevatron, which is about to start up its new equipment. They drive to the site and join a group led by a Negro tour guide, who provides expert info on the physics of the device [[ PKD seems to have done some research; there’s even mention of a Cockroft Walton generator, a real thing, p14b. ]] Then something goes wrong, the guide yells at them to stand back, the platform dissolves, and they all fall to the floor and experience great pain.

Chapter 3

- Hamilton and his wife wake in the hospital, feeling something is somehow out of place. Hamilton muses about needing a new job, perhaps his dream of designing new “tape recorder circuits… be a big name in high fidelity” (this is a crafty foreshadowing of the novel’s conclusion).

- They are driven home from the hospital with one of the other victims, Joan Reiss, who runs a book and art supply shop on El Camino. As they are driven home, a bee stings Hamilton’s calf (he’s just told a white lie). They reach the Hamilton’s home, and invite Miss Reiss inside for coffee. She reacts badly to their cat, Ninny Numbcat, and Hamilton finds her sufficiently annoying that he teases her about the cat’s habits — dragging in birds, snakes, gophers — until a shower of locusts descends from the ceiling. They clear them out, but Hamilton recognizes that this confirms that something strange is happening

- Here’s a list of the eight people who suffered in the accident:

- Bill Laws, a Negro grad student in physics working as a tour guide

- Jack Hamilton, an engineer and inventor

- McFeyffe, the security chief at Hamilton’s company

- Hamilton’s wife Marsha, whom McFeyffe suspects of being a communist

- Joan Reiss, a paranoid shopkeeper

- Arthur Silvester, a retired soldier and religious fanatic

- Edith Pritchet, a prim older woman very concerned about beauty and the arts

- Her son David, interested in studying nature

Chapter 4

- In the morning, Hamilton recognizes that perhaps some kind of divine judgement has descended upon him, for telling lies — Biblical judgments, bee sting and locusts. So he kneels down to pray, to ask forgiveness, even though he felt Miss Reiss deserved his mockery for her anti-cat attitudes.

- Bill Laws shows up and uses a metal charm to heal Hamilton’s bee sting — somehow such things work in this universe. Marsha wakes, describing a dream that suggests this isn’t real—that they’re really all lying on the floor of the Bevatron. They wonder what else works in this universe — is there really a Heaven?

- But Hamilton needs a new job. He drives up the peninsula to South San Francisco, to EDA, the Electronics Development Agency, to see an old friend, Tillingford, who welcomes him; it’s been years. Tillingford is happy to give Hamilton a job, but Hamilton is amazed as Tillingford pulls out a prayer wheel, then asks if Hamilton drinks or ever practiced “free love.” Tillingford pulls out a copy of the Bayan of the Second Bab, asking if Hamilton has “found the One True Gate to blessed salvation” p44.8. Hamilton pretends he’s been out of touch and asks Tillingford to explain the situation. Tillingford says EDA’s mission is one of communication, to ensure a wire open between Earth and Heaven, p46. Referring to Norbert Wiener and also to Enrico Destini’s work in theophonics — communication between man and God, of course.

- Hamilton is sent to Personnel, where his qualification test consists of opening the BSB at random to see whether a propitious verse is found, p49.8. Hamilton wonders about salary, and is told he can pray for, say, 400 a week. Hamilton wonders out loud if he should see a psychiatrist — and Tillingford reacts in horror, as if Hamilton blasphemed, and suggests instead he should see the prophet Horace Clamp, in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Chapter 5

- Outside in the parking lot several men in white lab smocks converge upon Hamilton threateningly, asking about his N-rating and wondering if he’s a heathen. They challenge him to stick his thumb in a flame. Hamilton calls them sadists, and Moslems (!) p55.0. He challenges them about electronics: what’s Ohm’s law?, before he realizes even he can’t quite remember it. Then an angel (!) floats down and speaks into one of the men’s ear. Hamilton becomes cynical, questioning the men’s’ motivations, until the landscape changes and everything becomes… damned.

- He manages to get into his car, using a prayer to get it started, and drives out of the damned zone… back into normal reality.

- He stops at his favorite bar, the Safe Harbor. McFeyffe is there, who also realizes the world has changed—but he’s adapting. He’s already collected a bunch of charms. When Hamilton suddenly has a pain in his gut — appendicitis? — holy water is fetched to heal him. McFeyffe is determined to “get on the inside” of this system, but Hamilton is still freaked out by where this “archaic system” has come from.

Chapter 6

- Laws is also there, and shows Hamilton the cigarette machine — there’s nothing inside! It magically replicates the sample in the window. They open up the machine and find the operative panel, and discover it will duplicate anything, even brandy. They could make a killing. Except that they really don’t want to stay in this universe.

- Hamilton meets a blonde barfly, Silky and prays for a drink for her, which appears.

- McFeyffe drives them both north into the city, San Francisco, to a Non-Babist Church. The church McFeyffe thought was there is now only a decrepit building. Inside McFeyffe asks Father O’Farrel to convert Hamilton. Hamilton presses him — how did everything get like this? The father has them hold an umbrella, sprinkles holy water on it, and recites some Latin. The umbrella lifts them up, through a skylight, and up into the sky.

Chapter 7

- They rise into the dark night sky, and into space, looking down on Earth; they pass tiny little objects that are the sun, the moon, the planets, as if Earth really is at the center of everything. Is this what’s true? Looking down, they see that far below the Earth… is Hell. And looking up, far above is what must be Heaven, with flitting specks that must be angels. They come to stop, and look down to see an enormous lake… and a lake with a lake. It’s an eye, no question whose. The eye causes the umbrella to pop, and they fall. All the way down to Earth, and land in the desert near… Cheyenne, Wyoming.

- Hamilton and McFeyffe walk toward town, seeing a big temple in the distance. They pray for cash and are showered with coins. McFeyffe plans to fly back to Belmont, and finds himself afflicted with boils and an abscessed wisdom tooth. So he stays. They board a bus for the temple.

- They meet the Prophet Horace Clamp in a vulgarly ornate temple. Clamp was informed of their coming by “(Tetragrammaton)”. [[ The parenthesized word seems to be PKD’s way to avoid using the word God. ]] Clamp explains about the One True Faith. Its history: how the first Bab was executed in 1850, etc. p94. Clamp suggests they get in touch with T.E. Edwards, to launch rockets to convert all the world’s people to the True Faith.

- They look around, hear monotonous hymns, are shown a wall plaque with a roll call of the faithful. Hamilton’s name isn’t there, nor are various heroes of history (Einstein, Lincoln, Gandhi); but Arthur Silvester’s name is there! Hamilton realizes what’s going on; now it makes sense.

- They return to Belmont (using the coins showered upon them for money, apparently) where Marsha has turned into a deformed monster — what Silvester imagines a radical college woman would look like, p101.

Chapter 8

- Several of accident victims meet Sunday morning, as all the TVs play loud sermons that can’t be turned off, and they head for the hospital where Silvester likes in bed.

- Hamilton explains: of the eight of them Silvester never lost consciousness. P105: “The free energy of the beam turned Silvester’s personal world into a public universe. We’re subject to the logic of a religious crank, an old man who picked up a screwball cult in Chicago in the ‘thirties. We’re in his universe, where all his ignorant and pious superstitions function.” And he’s probably not even aware of what’s happened; it’s the private fantasy-world where he’s lived in all his life.

- They find Silvester’s room; Mrs. Pritchet and her son David are there, and Laws. Mrs. Pritchet is concerned with giving her son a good education, about the classics and beauties of life, asks about museums and recites her favorite operas; Hamilton thinks she’s a bore. Laws speaks in primitive dialect as Silvester imagines Negros talk.

- Silvester, who wonders why they aren’t all praying, insists providence and faith saved him; the “accident” was a method by which Providence was testing them. The One True God is a stern God, 109. He insists that colored person (Laws) step outside. Hamilton replies angrily. Angels emerge from the TV and begin fighting them, until Silvester is knocked out — and the angels vanish.

- Have they won? They seem to be still in the hospital room. Or are they back at the Bevatron?

- But then Hamilton notices his wife change, from a monster, to a slender sexless figure. They’re in someone else’s world! How many times will this happen??

Chapter 9

- By Monday morning everything seems returned to normal. Marsha is quick to guess they’re in Mrs. Pritchet’s world, her Victorian view of the world, where women are sexless.

- Hamilton takes the train to his new job at the EDA, meeting Tillingford, who asks him how the contest went. What contest? Tillingford seems to think Hamilton took Friday off to enter his cat in a pet show. Hamilton hides his confusion by pretending stress and asks for a refresher about his new job p122. Tillingford explain, it’s to bring culture to the masses: “to turn the immense resources and talents of the electronics industry to the task of raising the cultural standards of the masses. To bring art to the great of mankind.” Hamilton is flabbergasted for a few moments… then gives in. He can’t fight it.

- He notices a magazine about Freud; Tillingford explains that Freud found there’s a sex drive only when the natural opportunities for artistic activity are suppressed, p125b.

- At the end of the day the barfly, Silky, is there to pick him up. She explains that she’s talked to his wife, they had a nice chat, and she’s driving him home! (Along the way he notes that in this world cars don’t have horns; Mrs. P would disapprove of them.)

- They stop at the bar, now redecorated with white tablecloths. The beer is great, through. Hamilton mentions wanting a steak, and Silky reacts in horror — he’s a savage!

Chapter 10

- They arrive home. Hamilton asks his wife if she knows what Silky does…? Marsha doesn’t believe what he tells her. In the newspaper there’s no news about Russia. Marsha thinks maybe this world isn’t so bad, which makes Hamilton angry. He realizes they can’t have sex; she’s not equipped. He decides to have sex with Silky, and takes her down to this basement stereo room, and finds his Bartok records gone. Doesn’t she want sex? He gives up. She feels odd…

- Pritchet arrives, and makes Silky simply vanished — and not just Silky, but “that category.”

Chapter 11

- The others arrive. Laws doesn’t mind this change, p148; he used to be a tour guide, and now he heads research in a soap factory. He goes on quite bitterly about his “real” life as a colored man subservient to whites, 148-9. Why would he want to go back?

- They gather for dinner; Mrs. Pritchet is annoyed by the cat, and makes all cats disappear. Silvester tries bashing her with a pitcher; both him and the pitcher disappear. Hamilton is still determined to knock her out somehow.

- [[ This section is of course very reminiscent of Jerome Bixby’s famous story (adapted into a Twilight Zone episode) “It’s a Good Life,” published four years earlier. ]]

Chapter 12

- Next day Hamilton drives the entire group south, for a picnic near Cone Peak. McFeyffe lights a cigar; Mrs. P makes it vanish.

- They reach Cone Peak, where insects and weeds have been removed; David is worried he’ll have nothing to study. They set up the picnic. Hamilton pours chloroform on a cloth and tries to sneak up behind Mrs P — but she smells it, makes the cloth vanish. So they eat.

- [[ PKD lived in the Bay Area for a while, and the place names are real: Belmont, El Camino Highway, South San Francisco, etc. Even Cone Peak. But the distances aren’t feasible; it’s 175 miles from Belmont to Cone Peak, which is half-way down the California coast. Bit far for a picnic! ]]

- They hear a plane; she makes planes vanish. Then dampness. Birds. Money. The woods. Shoes… This section becomes absurdist, as the others goad Mrs. Pritchet into making one thing after another disappear. Clothes! The elements! The air! And so the universe vanishes around them… But somehow they are still there. A voice speaks, the next person in charge: It’s Joan Reiss.

Chapter 13

- They’re still in Big Sur, on the hillside, everything apparently normal. Joan Reiss says she wants everything back to normal, the way things were, p176. She’s been planning this — she knew she was next, because the sequence of who’s in charge has been the order in which they regained consciousness after the accident. So she’s created the real world for them.

- They drive back to Belmont and are all dropped off at their homes.

- But the Hamiltons find their cat, in the kitchen, turned inside out, still alive.

- Joan Reiss is paranoid, they realize, 182m, convinced that everything is out to get her.

- Hamilton wants to listen to music, but as he descends to the basement finds himself engulfed by some huge web; Bill Laws and others arrive to free him. Whatever that thing is, it’s what used to be the barfly, who was vanished in the basement.

Chapter 14

- They agree they need to kill Joan Reiss. But will there be five worlds left? Perhaps they don’t all live in fantasy worlds… Bill takes offense. What about Marsha being a communist?

- Marsha tries to get a can of peaches, but it falls to the floor. When they get it open, it tastes of acid. These are all the things Joan Reiss is afraid of, that may be dangerous. The lights go out. The house seems alive; they struggle to get out, as the living room turns into a mouth… they make it outside, except for Mrs. Pritchet.

- Outside Joan Reiss awaits. See! They’re conspiring to kill her — she was right! She tells them that they’re not actually human beings. Indeed, they are all now giant insects, and attack Joan Reiss. Laws stings her. Silvestri binds her in some kind of wet cement web. David attacks and feeds off her. These are their real shapes, they realize, p205.

- Then the world expires; they’ve killed Joan Reiss. They’re still on the lawn in front of Hamilton’s house. And men in a black car are there, led by Dr. Tillingford.

Chapter 15

- The car dissolves. Bricks are thrown from the darkness, and they find themselves in the middle of some kind of street battle. It’s a world full of Communists; is this Marsha’s world? But this vision is a parody of what Communists believe of Americans, p217, a fantasy. They flee the battle, running into town, again seeing a Communist idea of America, with lavish restaurants and shops along with slums and refugees in the streets.

- They come to the bar, Safe Harbor, now occupied by young kids. Silky is now hugely endowed. Outside is a battle between “bloodsucking vampires of Wall Street versus heroic, clear-eyed, joyfully-singing workmen.” 223top. This kind of talk goes on and on. Finally, Hamilton knocks Marsha out — and nothing changes. It’s not her world!

Chapter 16

- It’s McFeyffe’s! He’s the one paranoid about Communist takeover, complete with the Communists’ fantasies of corrupt American life. Here we get some pointed political commentary from PKD. Hamilton: “You’re not a bad guy, in a way. But you certainly are twisted around inside. You’re more insane than Miss Reiss. You’re more of a Victorian than Mrs. Pritchet. You’re more of a father-worshiper than Silvester. You’re the worst parts of all of them rolled together.” P230b

- And yet McFeyffe truly believes Marsha is the dangerous one: he understands “lunatic patriots,” but not people like Marsha, those who attend suspect meetings but also read the Chicago Tribune. He tells Hamilton: “The cult of individualism. The idealist with his own law, his own ethics. Refusing to accept authority. It undermines society. It topples the whole structure. Nothing lasting can be built on it. People like your wife just won’t take orders.” P231.

- And so Hamilton attacks him…

- Until they all wake up back in the Bevatron. [[ And implicitly in the “real” world, since Hamilton himself, wife Marsha, Bill Laws, and the boy David don’t believe in some kind of fantasy version of reality? Or perhaps the novel was long enough and PKD decided to wrap it up? ]]

- A week later, Hamilton speaks to T.E. Edwards, giving new testimony about McFeyffe, how he’s been using his position to weed out opponents to the Communist party. But he has no evidence, no case, and Edwards dismisses him. What will Hamilton do with his life now?

- Hamilton meets Bill Laws where they are building a business to create high-end phonographs!

- And Mrs. Pritchet, patron of the arts, arrives, ready to invest, and writes them a check. Bill yells, “What are we waiting for? Let’s get to work!”

Comments

- The end wraps things up more neatly than I’d expected from PKD’s make-it-up-as-you-go-along plotting, even if you never learn what happened to some of other characters.

- Despite the somewhat arbitrariness of the plot, PKD is quite inventive in imagining details of these various worldviews, especially the vision of the Biblical fundamentalist’s conception of the universe.

- Yet as in Time Out of Joint, the novel just sorta keeps going until it’s long enough to be a novel, then wraps up. There could easily have been less, or more.

- As in most other ‘50s novels, men are referred to by their last names, women by their first, or via a title, e.g. “Miss Reiss.”

- In all three books, especially the two below, PKD is frank to the point of bluntness about sexual needs (without in any way setting them in the context of love or romance).

- I think it pays not to think about the premise of a PKD story too much. In this one, it’s what? Something weird has taken place because of nuclear energy, or perhaps radiation: “The free energy of the beam turned Silvester’s personal world into a public universe.” Does this make sense? Probably not. Radiation was a go-to danger in 1950s SF books and movies; think Matheson’s The Shrinking Man, and that movie about giant ants.

- And yet — here is how PKD redeems his shoddy science: the situation is powerfully metaphorical. Perhaps especially so today — or has it always been thus? Now we can reflect on the fractured state of culture in the US and other nations, with divides between right and left, between science and religion, so wide it’s as if the opposite camps are living in alternate universes, operating to completely different rules than those on the other side, simultaneously.

The Other Two Books

Solar Lottery–

Solar Lottery by Philip K. Dick; First Edition: Ace, 1955.

Cover art uncredited. (Click to enlarge)

I found Solar Lottery a difficult read. The opening chapter is almost incomprehensible. (I read it a second time before moving on.) PKD throws everything about this future society — with its Quizmaster, its teeps, its Hills, its assassin challengers, its principal of Minimax, all at once in the first few pages… and then as the plot unfolds, has his characters discuss these matters over and over.

Unlike Eye in the Sky, which maintains a consistent point of view from Jack Hamilton, the POV in this once bounces around. Initially with Ted Benteley, who’s been in effect laid off from Oiseau-Lyre Hill and attempts to make at oath to the Quizmaster, but then switching POVs to other characters, some of them relatively minor. Is this deliberate, a way of keeping the reader off-balance? Or just a pulp writer’s hasty solution to explaining an intricate premise?

The science is that out of a Superman comic. A central plot concern is an assassin named Pellig, who is actually a “synthetic,” operated remotely by various operators (in order to foil the teep [telepathic] corps protecting the Quizmaster), and since he’s a synthetic, why, he can launch himself into space, just like Superman, for a quick trip to the Moon, or even deep space…

Time Out of Joint—

Time Out of Joint by Philip K. Dick; First Edition: Lippincott, 1959.

Cover art Arthur Hawkins. (Click to enlarge)

This much better PKD novel is about a 45-year-old man with the unlikely name of Ragle Gumm, who lives with his sister and brother-in-law in a small town in (apparently) 1959. Ragle doesn’t have a job; he spends his days solving daily puzzles in the local paper, and is the all-time winner. His reality starts to break down, in classic PKD fashion, one day during a visit to a park where a vending cart shimmers and disappears, to be replaced by a strip of paper with the words: “Soft-drink stand.”

It develops that this 1959 town is a fiction; outside the town, it’s 1998, and Ragle’s talent for choosing the right square in a grid in this daily contest corresponds to (in a frankly fantasy premise) the actual locations of missile strikes on Earth from Lunar attacks, in an ongoing war between Earth and Luna. (Had Orson Scott Card read this novel, I wonder?) The novel proceeds as Ragle detects discrepancies in his world, escapes the town, and gradually discovers the truth. (The film The Truman Show is analogous, to a point.) In an ironic conclusion, we’re given to understand that, were it not for Ragle’s ability to detect the attacks, the war would have been concluded long before.

My problems with this book are two. We’re told by the end that the town where Ragle lives is a real place in Idaho, dressed up to look like a 1950s town (to avoid some trauma of Ragle’s by placing him in a reassuring childhood environment), and that most of its residents have been conditioned to behave like 1950s adults (while a few like the neighbor Bill Black, are in on the conspiracy). So, it’s a real, physical town. Then why the dissolving drink stand, and later a bus, as if the town is some sort of conditioned hallucination? (My guess is that PKD charged along writing much of the book before figuring out quite how he was going to explain it.)

My second issue is that it’s baggy in its middle, with an extended escape sequence and highway pursuit that doesn’t seem to serve any purpose other than filling the story out to novel length.

Generalizations?

While it’s risky to generalize about PKD’s themes and the attraction of his stories on the basis of just three novels, what occurs to me is that they are all about recomplication. They take a premise and steadily undermine it or change its parameters. The earliest book here isn’t about what’s real, it’s about a complicated social order and about who rules and who is oath-bound to whom else, but the novel barely begins before the rug is pulled from under the main character, and the roles the characters play change again and again. It took a few books before PKD’s reality-bending themes appeared, but they too involve rugs being pulled from under characters in more profound ways.

A Surprising Theme

One more idea is surprising and perhaps significant. In both Solar Lottery and Time Out of Joint, there are final passages that affirm humanity’s need to explore and expand into the universe.

Solar Lottery ends with a subplot about the exploration of a 10th planet. Last lines:

“it’s the highest goal of man — the need to grow and advance… to find new things… to expand. To spread out, reach areas, experiences, comprehend and live in an evolving fashion. To push aside routine and repetition, to break out of mindless monotony and thrust forward. To keep moving on…”

And Time Out of Joint ends with Ragle realizing that the expansionists on Luna are right (not the Earthers whose motto is “One Happy World”) and about to switch sides, defecting to join the “lunatics.” Why? P245:

No migration had ever been like this. For any species, any race. From one planet to another. How could it be surpassed? They made now, in these ships, the final leap. Every variety of life made its migration, traveled on. It was the universal need, a universal experience. But these people had found the ultimate stage, and as far as they knew, no other species or race had found that.

…And the ironic thing, he thought, is that people say God never meant for us to travel in space.

These sentiments were commonplace in the 1950s, of course, but they seem oddly out of place amidst PKD’s paranoid worlds in which reality can’t be trusted. So I’ll keep reading PKD novels (but probably not all of them) and see how these themes develop. PKD strikes me as a writer, like J.G. Ballard, who in his obsessive reworking of a handful of themes, created a body of work more significant than any particular titles.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

That PKD’s characters are rarely sympathetic is a statement that goes contrary to my reading of him, that’s for sure.

OK I’ll walk that comment back a bit. Ragle Gumm is sympathetic. Jack Hamilton is sympathetic, and so is Bill Laws. But the overriding impression I had from all three books, especially Eye in the Sky, is how unpleasant most of the characters are.

I think part of the contradiction may come from the fact that while many of PKD’s characters might be objectively unsympathetic, Dick himself had great sympathy for them, no matter how big a train wreck they were. He’s different in this way from someone like Heinlein, who clearly reserves all of his esteem for the strong and competent winners of the world.

There is something dazzling about PKD – not just the whole gnostic thing – but how he expresses his ideas. He has a great knack for the telling detail – the vending machine in ‘Eye in the Sky’ is a good case in point. He also has the same flair for setting up a character and a situation. But most of his books don’t have a second act, or even a middle act. It’s kind of weird that an author who’s able to establish believable characters from the get-go, then has no idea what to do with them.

I liked TIME OUT OF JOINT a lot more than you did, and I disliked SOLAR LOTTERY to about the same degree you did.

My reviews: TIME OUT OF JOINT: http://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2019/05/a-lesser-known-philip-k-dick-novel-time.html

SOLAR LOTTERY: https://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2019/10/ace-double-reviews-115-solar-lottery-by.html