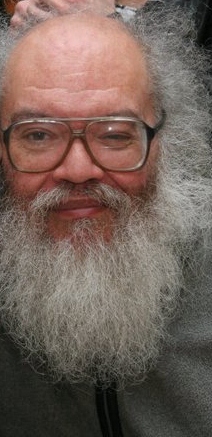

Charles Saunders, Father of Sword & Soul, July 1946 – May 2020

“I started reading more about the history and culture of Africa. And I began to realise that in the SF and fantasy genre, blacks were, with only few exceptions, either left out or depicted in racist and stereotypic ways. I had a choice: I could either stop reading SF and fantasy, or try to do something about my dissatisfaction with it by writing my own stories and trying to get them published. I chose the latter course.”

–Charles R. Saunders

Sword & Sorcery is one of Fantasy’s (or perhaps, to call it by its other term, Weird Fiction) oldest sub-genres, reaching back to the first decades of the 20th Century, as a “weird” outgrowth of the fantasy historical adventure fiction that had flourished in the 1880s – 1920s.

A great deal has been written about the the antecedents of Sword & Sorcery (especially by the tireless Deuce Richardson) and the first generation of writers (giants like Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, CL Moore, and Henry Kuttner), and those who carried the flickering torch forward during the dark days of the mid-century — writers like Fritz Leiber, Michael Moorcock, Poul Anderson and the loved-hated Lin Carter — and brought that legacy to the second great wave of S&S that flourished in the 60s and 70s, where we met the likes of John Jakes, David C. Smith, Richard Tierney, and Keith Taylor.

Today I want to talk about a man from that second flourishing of the Third Generation who, in my opinion, stands apart, because he was also the father of an entire genre only now beginning to see its potential — Sword and Soul.

Charles R. Saunders was born at the start of the Baby Boom in Elizabeth, PA, a small town near Pittsburgh, moved to the Philadelphia suburbs, and was educated at Lincoln University, a historically black institution in Pennsylvania from which he graduated in 1968 with a degree in Psychology. The next year he moved to Canada, where his life as a writer began, primarily, as fate would have it, as a journalist — both as an editor, but also as an editorialist and columnist.

With a somewhat restless intellect, he didn’t just fall into journalism and stick — his life was a wandering, as writers often do, from lowly cut-and-paste editor, to scholarly writer, to teacher, and then at last to columnist. He slowly worked his way east through Canada, settling at last in Nova Scotia in 1985.

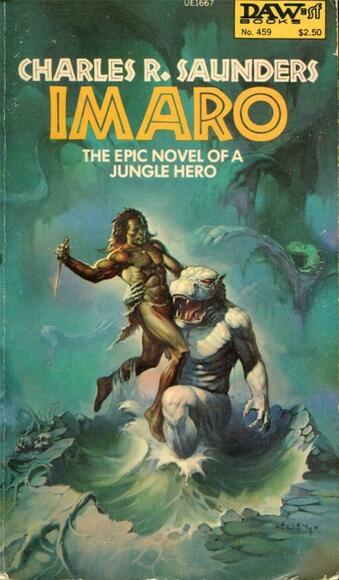

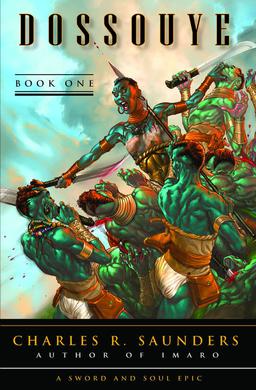

Imaro (DAW, 1981, cover by Ken Kelly), with the original “Black Tarzan”

cover blurb that brought the threat of a lawsuit and forced a reissue

With a deep love of scifi and fantasy, Saunders, a man living through the Civil Rights-era, was painfully aware that Black characters in the genre were either absent, “the buddy or henchman,” or stereotyped cartoons, especially when portraying Africa or African-based settings. Having developed a keen interest in African history, culture and folklore, he combined those passions with an urge to write fantasy fiction and invented his own Hyborian Age, drawing from the diverse tapestry of Africa.

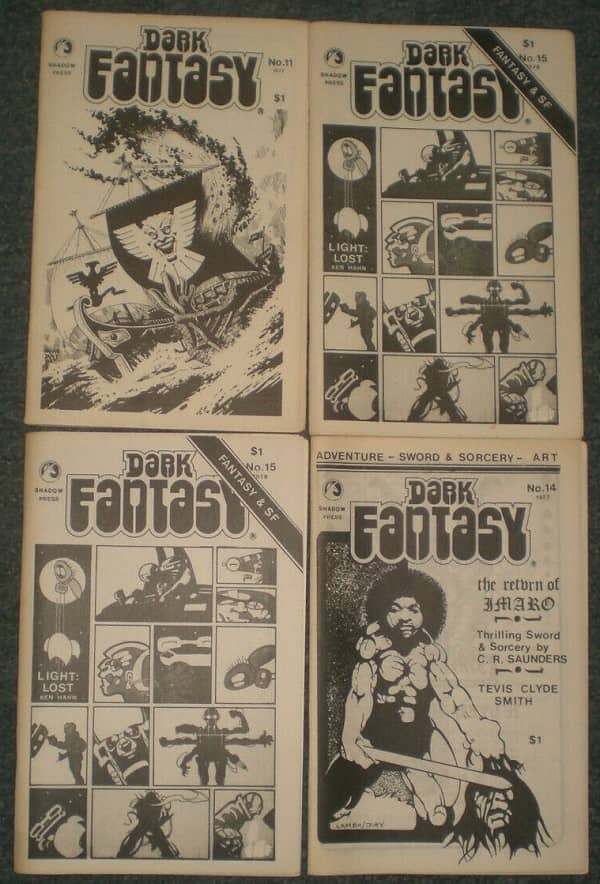

Dark Fantasy fanzine, 1977-78, featuring Charles Saunders’ Imaro; back covers here

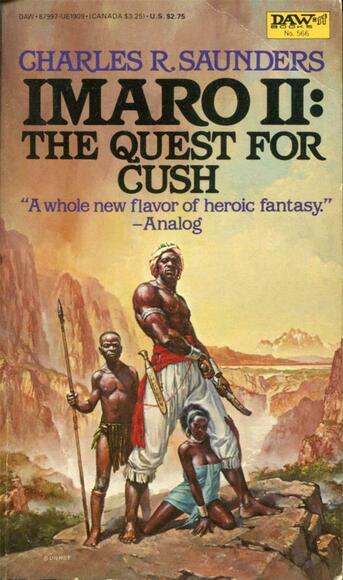

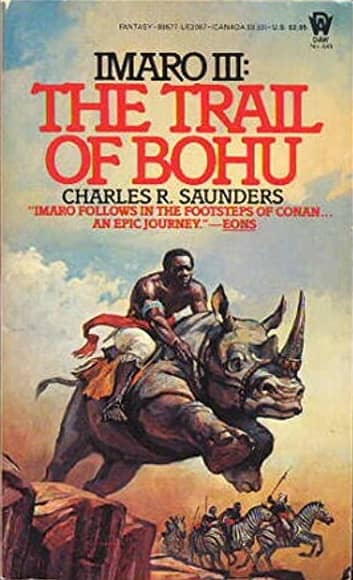

Hither came Imaro, a warrior of the lion-hunting Ilyassai, of unknown paternity, self-exiled to tread the vast savannahs, deep rainforests, and jeweled thrones of Nyumbani beneath his sandaled feet, loyal Bambuti pygmy scholar, Pomphis at his side. The original cycle of six short stories (“Mawanzo,” “Turkhana Knives,” “The Place of Stones,” “Slaves of the Giant Kings,” “Horror in the Black Hills,” and “The City of Madness”) first appeared in Dark Fantasy, a Canadian fanzine published during the 1970s, before being issued by DAW as Imaro, the stories lightly massaged to create an episodic novel. This was 1981, and two more titles followed, The Quest for Cush in 1984 and The Trail of Bohu in 1985.

|

|

|

Imaro (reissue edition, note the new blurb), Imaro II: The Quest for Cush (1984), and

Imaro III: The Trail of Boho (1985). DAW paperback originals; covers by Ken Kelly, James Gurney, and James Gurney

Dwindling sales led to the series being canceled without a resolution, but blessedly, self-publishing rescued Imaro, and Saunders, from obscurity. In 2009, Saunders released The Naama War, the fourth and latest Imaro novel through Lulu.

Imaro was finished, but Saunders was not. The world was changing, and digital printing made small publishing far more viable. Likewise, there was a slow-growing understanding of the need for more representation, and Saunders, the old griot (an African bard), was ready to sing Sword & Soul back to life.

|

|

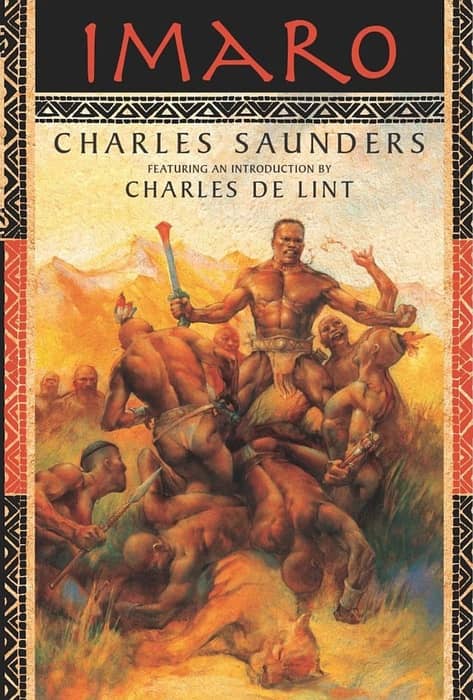

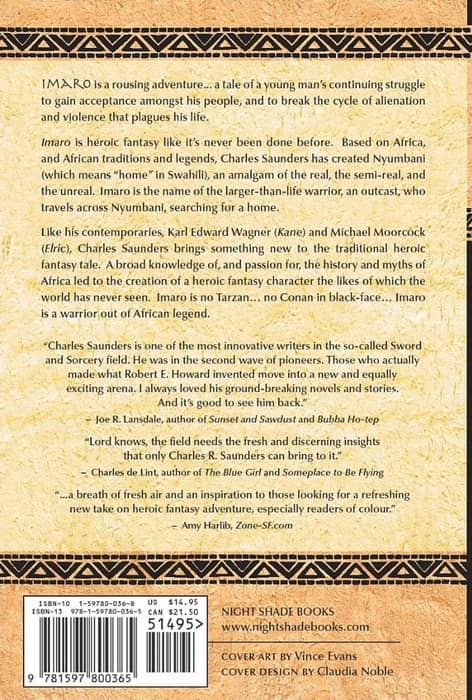

Imaro by Charles Saunders (Night Shade Books reprint, 2006), cover by Vince Evans

Besides The Naama War, he responded with the adventures of Dossouye in 2008. Based on the real Dahomey warrior women, Dossouye had also seen life in short-story anthologies of the 70s and 80 (“Agbewe’s Sword,” “Gimmile’s Songs,” “Shiminege’s Mask,” “Marwe’s Forest,” and “Obenga’s Drum”), reworked as a fix-up novel. In 2012, Saunders published a sequel Dossouye: The Dancers of Mulukau.

Sword & Soul was back!

Working with Milton Davis, who has pushed Sword & Soul in various directions (short stories, novels, an RPG), Charles was there with both contributions of his own, and his editorial pen. He also returned to Nyumbani with the subtly named Nyumbani Tales, which Fletcher Vredenburgh reviewed for Black Gate.

Working with Milton Davis, who has pushed Sword & Soul in various directions (short stories, novels, an RPG), Charles was there with both contributions of his own, and his editorial pen. He also returned to Nyumbani with the subtly named Nyumbani Tales, which Fletcher Vredenburgh reviewed for Black Gate.

For a decade, Saunders has been the griot singing the song of Sword & Soul to new audiences, but this May, the bard fell silent, and it is only now, we are learning the terrible news in this most terrible of years.

So, here I sit, a middle-aged white man talking about the Father of Sword & Soul, feeling very self-conscious about this in a year of BLM protests, the loss of Chadwick Boseman and the sometimes painful reminders of the ugly history of racism in America — and in pulp literature — provided by HBO’s adaptation of Lovecraft Country. But then, you see, I think that is the beauty of what Marvel’s Black Panther, or Saunders’ Nyumbani really teach us: Good fiction and good secondary worlds are there for all of us.

Saunders wanted heroes that looked like him, but he wanted everyone to see why Africa was a rich, beautiful setting for fantasy that everyone could love, just as he, a Black man, had loved the works of Howard or Bradbury. Because of him, I have books on African Arms and Armour, the history of Ethiopia and the great empires of Benin and Ghana; I have investigated African martial arts and learned about heroes like Sundiata. Imaro opened that world up for me, and I will be forever grateful.

Long before we were celebrating Marlon James’s Black Leopard-Red Wolf and its portrayal of mythic Africa, Saunders was doing it better, first. He is one of the towering figures of that third generation of Sword & Sorcery, but he is also the Father of Sword & Soul, an innovator and fine writer, who deserves to remain in print, and be long remembered. The world has grown a little dimmer, the path to Nyumbani more tenuous… the griots calls for others to take up torches and light the way.

Charles Saunders was partly responsible for my love of fantasy.

When I was a young teenager (or maybe even pre-teen) I came across the Year’s Best Fantasy Stories anthologies edited by Lin Carter in a used bookstore. I think every year that was edited by Lin had a Charles Saunders story which I greatly enjoyed.

I kept an eye out for books that had a Charles Saunders story such as Amazons!, Sword and Sorceress and Hecate’s Cauldron. I purchased the Imaro book but was slightly disappointed that it was a fix up instead the original stories.

But then Charles seemed to stop writing fiction. I was delighted when a Blackgate article highlighted a new (old) Charles Saunders book Nyumbani Tales. I purchased the book that day. I think it was a damn shame that Nyumbani Tales did not win a World Fantasy Award for best collection. It was that good. I purchased the anthology The Mighty Warriors partly because it contained a new Imaro story by Charles Saunders.

I am saddened that Charles Saunders is no longer with us but his stories will be immortal.

RIP, Mister Saunders…!

Believe it or not, I like his works too.

I just grabbed Quest For Cush, it’s getting rare now. Hope to start the first book soon.

[…] to Black spec-fic. On the other hand, Sword & Soul founding father George R. Saunders passed away without fandom noticing for […]

[…] through the efforts of many of his fans. Salutes to his memory have appeared from Jon Tattrie, Greg Mele, Brian Murphy, and David C. […]

I am a huge fan for his work, I really miss them now.

I just grabbed Quest For Cush, it’s getting rare now. Hope to start the first book soon.

Sad to hear that he passed. I’ve started reading his work and found it to fill a hole I didn’t know I had. It really goes to show representation is important and I’ll always be thankful to Saunders for showing me that.

[…] everyone could love, just as he, a Black man, had loved the works of Howard or Bradbury,” wrote Black Gate Magazine’s Greg Mele after learning of the passing of “the Godfather of Sword & […]

What a beautiful tribute to a true legend. Charles R. Saunders didn’t just write stories—he opened a whole new world in fantasy. His Imaro and Dossouye tales weren’t just adventurous; they wove African culture, folklore, and history into something fresh and vital. “Sword & Soul” stands as a testament to creativity and representation. Thanks to Saunders, fantasy became more than escapism—it became a richer, more inclusive place.

Thank you for sharing this heartfelt tribute to Charles R. Saunders. I feel humbled learning how he reshaped fantasy and created Sword & Soul a genre rooted in African myth and culture. Imaro’s stories are powerful and vivid, and I appreciate how Saunders brought representation and depth to a genre that lacked it. His work inspires me, and it’s clear his legacy will continue to grow in readers’ hearts.

Just picked up Quest For Cush — hard to find now. Can’t wait to start with the first book.

Managed to grab Quest For Cush before it gets any rarer. Looking forward to starting the series from book one.

A great tribute to Charles R. Saunders. His work and the sword & soul genre left a lasting mark on fantasy. Thank you for honoring his legacy.

Thank you for this moving and informative tribute. Charles R. Saunders’ work opened doors that fantasy readers didn’t even realize were closed, and Imaro remains powerful and relevant decades later. His vision, persistence, and imagination helped reshape the genre in lasting ways. He will be deeply missed, but his legacy lives on through Sword & Soul and the writers he inspired.