These Two Books Are Not the Same: John Wyndham’s The Kraken Wakes and Out of the Deeps

The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham; First Edition: Michael Joseph, 1953

Cover art uncredited

The Kraken Wakes

by John Wyndham

Michael Joseph (288 pages, 10/6, hardcover, 1953)

Cover art uncredited

Out of the Deeps

by John Wyndham

Ballantine (182 pages, $2.00, hardcover, 1953)

Cover by Richard Powers

John Wyndham was an English author, popular for five or six major novels published in the 1950s and 1960s, among numerous other books. The first of his famous novels was The Day of the Triffids (1951), about murderous walking plants and a meteor shower than causes most of humanity to go blind. Several following novels were also catastrophes of various sorts, and were published both in the UK and the US, though sometimes with variant titles. The second of these was The Kraken Wakes (UK 1953), about aliens who settle into Earth’s oceans, attack cruise liners, and subsequently wreck the climate and the world economy. It was published in the US by Ballantine as Out of the Deeps (also 1953). What I discovered only recently was that the two books are of course very similar but not identical, and nothing in either edition (in particular the US edition, presumably the second published), indicates any such differences. In fact Ballantine’s copyright page claims “This novel was published in England under the title The Kraken Wakes” which is, in fact, not literally true.

Title changes from UK to US editions were not frequent, but weren’t unusual either. A later Wyndham novel appeared in the US as Re-Birth, and then in the UK as The Chrysalids. The most famous UK/US retitled book of all time is likely the first Harry Potter novel, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone in the US. Some of these cases can be understood due to variants in the language between the two countries; kraken, and philosopher’s stone, e.g., are presumably less familiar to Americans than to Brits. Yet whether editions of such re-titled novels are actually, essentially, the same book is generally not evident from copyright pages. Some changes are well-known but anecdotal, like the changes in the text of the Harry Potter books (all of them? At least the early ones), again to substitute American colloquialisms for British ones.

Out of the Deeps by John Wyndham; First Edition: Ballantine 1953

Cover art Richard Powers

As it happens, I first read Wyndham’s Out of the Deeps in 1971, I think perhaps in the paperback Hitchcock anthology Slay Ride (www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?1845), but didn’t own a separate copy of the book until the December 1977 Ballantine fifth printing. (As it turned out, this was Ballantine’s last printing of the book, and so the last edition of the US version of this novel.) Some years later, I think perhaps at a Worldcon (it was September 1988), I bought a copy of the UK version, The Kraken Wakes, not because I thought it was a different book, but to revisit the novel under its British title, which I did later that month. But I did not exam the two versions side by side.

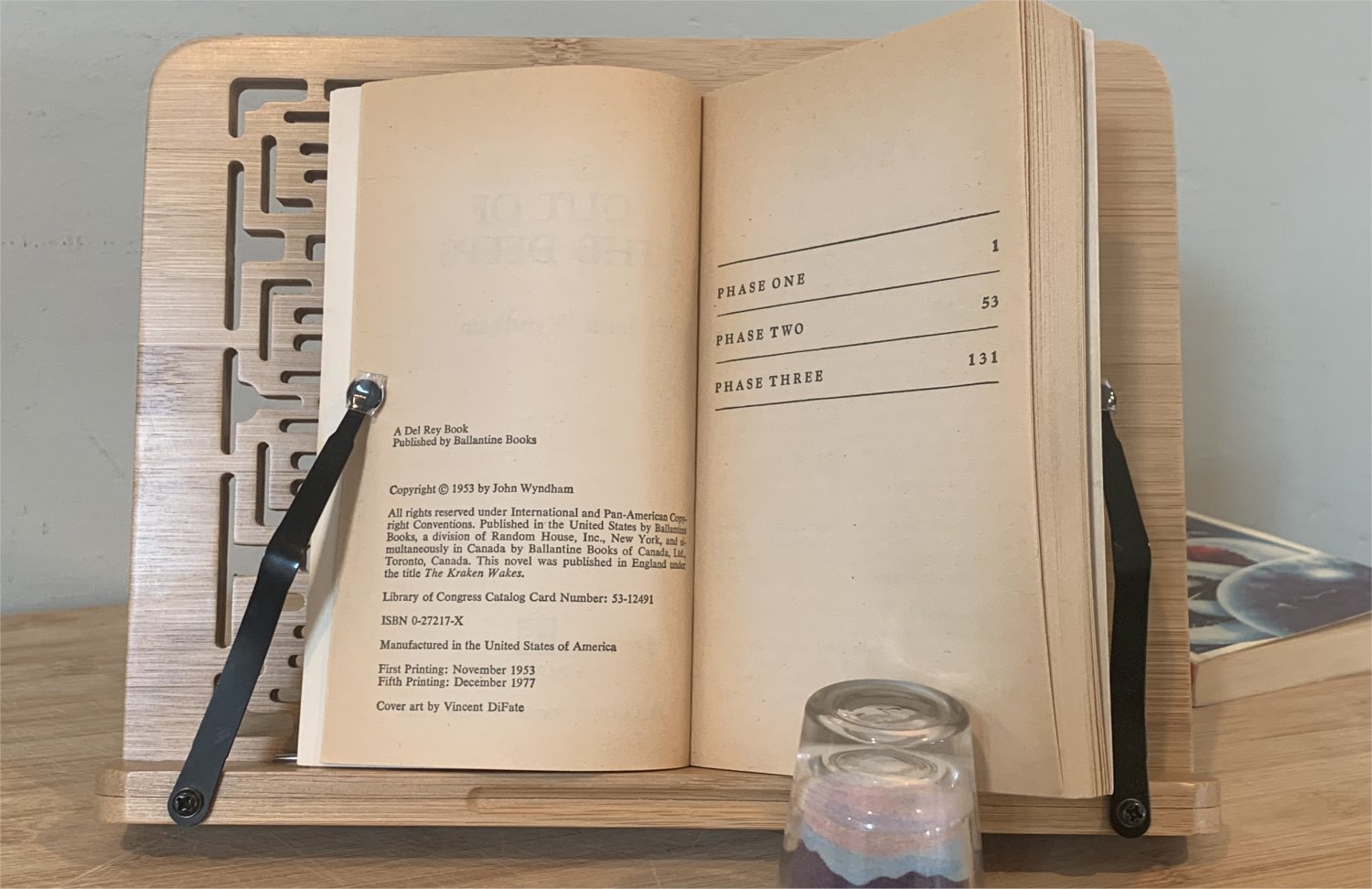

Rereading many of the classic 1950s novels over the past couple of years, I reread Triffids last year, having only a US paperback edition, and then early this year picked up my copies of Out of the Deeps and The Kraken Wakes. The point of this elaborate introduction is because it was now evident, at a glance, that there was some discrepancy between the two. Out of the Deeps in the Ballantine edition is 182 pages of medium-sized print. The Kraken Wakes, in the 1980s Penguin edition I’d purchased, is 240 pages of smaller print. And opening the books shows an immediate textual difference: the UK edition has an introductory “Rationale” completely missing from the US edition.

So this time I reread both books, side by side, noting differences between the two.

Of course this is an academic issue, since the US version hasn’t been in print since 1977; anyone looking for old Wyndham novels to read would find only the UK version with the Kraken title.

And in either version it’s a substantial, suspenseful novel, in part a “cozy catastrophe” and in part an alluring tale about mysterious, inexplicable aliens. And also, from a contemporary perspective, a novel about climate change and existential threats.

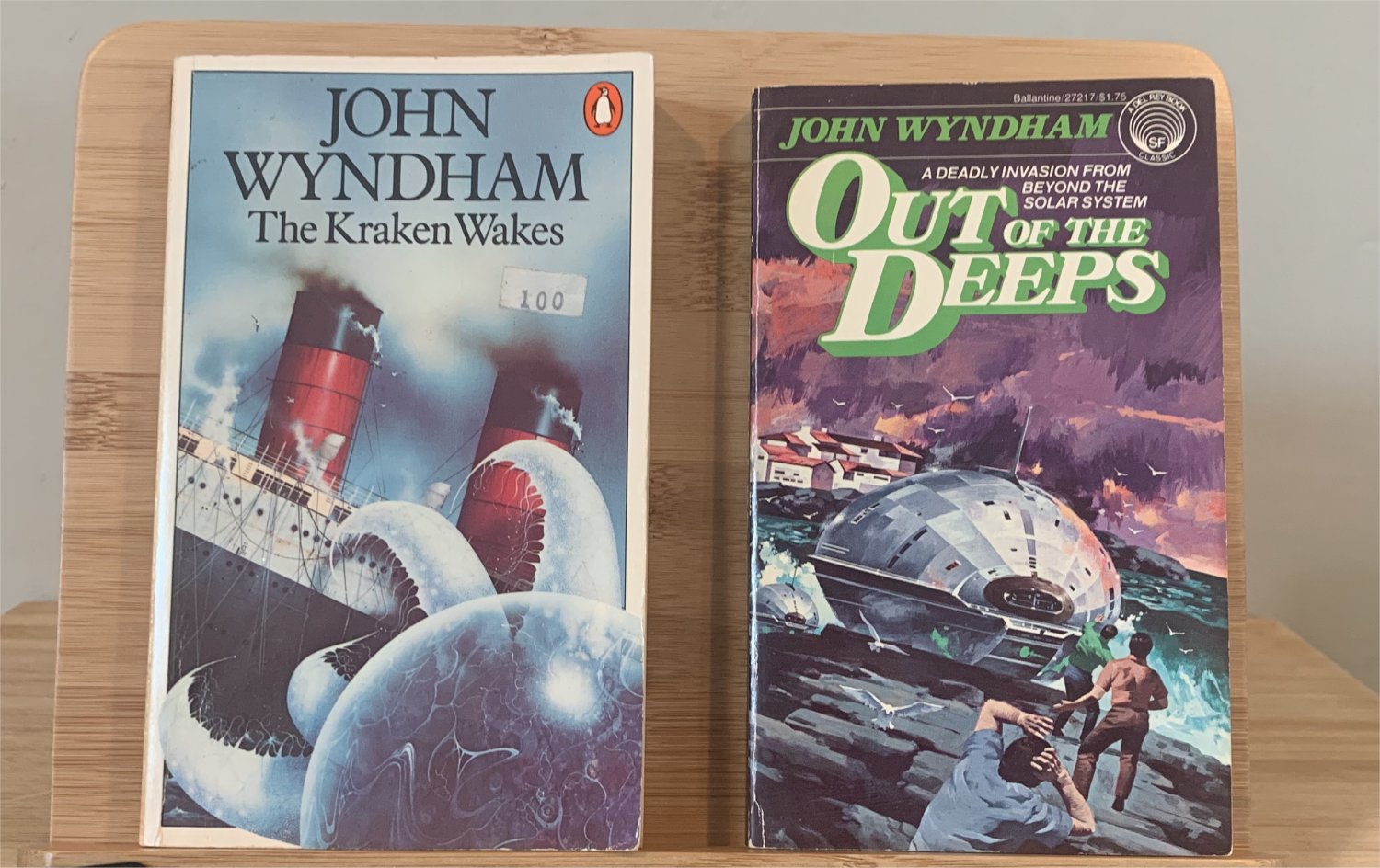

The two editions read for this review:

The Kraken Wakes, Penguin 1981 printing, cover illustration Peter Lord;

Out of the Deeps, Ballantine 5th printing, December 1977, cover art Vincent DiFate. (Click to enlarge.)

Gist

Mysterious aliens, arriving on spaceships that fall into the oceans, attack ocean-going vessels and send “sea-tanks” onto island shores (perhaps to collect specimens) that kill people and leave coatings of slime in their wakes. (These two themes are illustrated on the paperbacks above.) The aliens remain unseen, and their tactics change as they cause ocean levels to rise, flooding cities and wrecking the world economy. Radio reporters Mike and Phyllis Watson follow news from around the world, and witness one island attack, before fleeing London for their isolated Cornwall cottage. A deus ex machina solution appears to kill the unseen creatures, and our heroes are confidant humanity will recover.

Gist of UK vs US differences:

The bulk of differences are cuts from the UK to the US edition of sections of dialogue, many arch and full of Britishisms, that the Ballantine editors (Ian and Betty, remember), presumably felt US readers would not understand, or warm to. There are a great many of these, sometimes pages at a time, only a few noted in the summary below. Or perhaps these passages were cut simply to tighten the novel, which they do effectively. More substantially, the US edition omits from the UK edition an introduction (“Rationale”) and a flash-forward at the beginning of the third section; these have the effect of leaving matters in suspense throughout the book, while the UK edition’s “Rationale” reveals the characters have survived and are happy, making that version much more a “cozy catastrophe” then the US. Finally, the US edition expands the perfunctory UK ending.

Take

This is a first-class world disaster novel told as a mix of conversations, second-hand news reports, and scientific speculations; most of the action is off-stage, with three major exceptions. It’s partly also a story about mysterious aliens, though the apparently intelligent invaders who take up dwelling in Earth’s deep oceans remain inexplicable and are never contacted. The principle theme, then, is how humanity deals with an existential crisis. Writing this in July 2020, it’s hard not to see the similarity of the novel’s reactions of the British public, to the degree they realize this alien invasion is truly a problem and not a manufactured hoax, with the current American coronavirus response.

Summary

Our main characters are Mike Watson (the first-person narrator), a journalist for the EBC (not the BBC, he clarifies), and his wife Phyllis, who writes radio documentary scripts. The book is divided into three “Phases,” with an introductory “Rationale” in the UK version.

Rationale

Mike and Phyllis watch icebergs in the English Channel (!); we’re in the future looking back on the events of the novel. Mike ponders writing a book about this whole affair. He’s concerned about a proper epigraph, and settles on a passage from Tennyson, shown on page 10, about the Kraken. These three pages are full of banter between husband and wife, virtually all of which, throughout the book, were cut in the US edition. I’ll quote just one little sample:

“Now, if I were you I should divide the whole thing into three phases. It falls naturally that way. Phase One would be—”

“Darling, whose book is this to be?”

“Ostensibly yours, my sweet.”

“I see — rather like my life since I met you?”

“Yes, darling. Now, Phase One — Gosh! Look at that!”

As they see an iceberg. You can see how the deletion of many passages of such dialogue changes the nature of the US edition.

Phase One

- Mike and Phyllis are on a honeymoon cruise in the Atlantic when, late at night, five glowing lights appear in the sky and fall into the sea, causing great bursts of steam. The ship circles back, looking for survivors, but finds no one. Captain Winters declines to speculate. Mike returns to work, submits a report, and gets correspondence from radio listeners back. He reflects on them, UK page 16:

There must, I think, be a great many people who go around just longing to be baffled, and who, moreover, feel a kind of immediate kin to anyone else who admits bafflement along roughly similar lines. I say ‘roughly’ because it became clear to me as I read the mail that classifications are possible. There are strata of bafflement. A friend of mine, after giving a talk on a spooky experience, was showered with correspondence on levitation, telepathy, materialization, and faith-healing. I, however, had struck a different layer. Most of my correspondents assumed that the sight of the fireballs must have roused me to a corollary interest not only in saucers, but showers of frogs, mysterious falls of cinders, all kinds of lights seen in the sky, and also sea-monsters.

- The news story fades until more sightings come in — now larger groups of passing fireballs over northern European countries, slowing as if heading for the Atlantic — and by implication, having come from Asia. The Soviets only respond that they’ve shot some down. There are more sightings of fireballs and eventually people take them for granted, as if some kind of natural phenomenon. Maps of sightings are compiled, all in areas of deep water. If it’s not the Russians, are they… extraterrestrials? Mike is invited on an expedition to investigate one of the deep-water sites.

- (Here’s the first of three big action scenes in the book.) The expedition arrives at the Cayman Trench, where a Bathyscope is sent down with two technicians aboard. The men see fish; a whale?!; they stop at 1200 fathoms. They see nothing. As they ascend they do see something… something big. It passes above them — and then their voices, and the screen, go dead. When the winch comes up, the strands at the end are fused together. Another device is sent down; they see a vague oval shaped thing, and the screens go blank.

- Phyllis writes a documentary script about the incident, but the government won’t let it be released. The issue about the fused cable suggests some inconceivable hazard. The Americans send a second expedition — and lose their entire ship. A witness tells about seeing the ship surrounded by lightning, before it blew up. Other expeditions follow, but again, after a while, the subject fades from public interest.

- Three years pass. Mike and Phyllis have a baby that dies at 18 months. They travel.

- Ships still occasionally disappear. An American cruiser goes down; a Russian ship sinks. Norway loses a survey vessel. Others. Then an American destroyer. One country drops an atomic bomb underwater.

- Mike and Phyllis meet a renegade scientist, Alastair Bocker, who speculates that some alien intelligence, from a high-pressure world, perhaps Jupiter, has invaded and is taking refuge in our oceans. He suggests an amicable contact should be made. But his paper on the matter is rejected by the government and by all the newspapers. And he refuses to be printed by the tabloids. A nice characterization of Bocker, UK edition page 49.7:

He’s a civilized, liberal-minded man — with the usual trouble of liberal-minded men; that they think other are, too. He has never grasped that the average mind when it encounters something new is scared, and says, “Better smash it, or suppress, it, quick.” Well, he’s just had another demonstration of the average mind at work.

- By this time the public puts pieces together and demands action. The British drop their own atomic bomb. Suspicions swing back toward the Russians.

- Phyllis gets an interview with an oceanographer, Dr Matet, who talks about ocean currents, and oozes, and how sediments from the greatest depths are appearing. Not caused the bombs, and not by earthquakes. He’s not worried, just puzzled.

- Phyllis and Mike meet Bocker again; he extends his theory: the creatures are adjusting their new environment to their taste. Perhaps they are mining for metals themselves. An atomic bomb that originally didn’t go off does go off, 1200 miles from where it was lost. (Oddly, these three are unfamiliar with the words ecology and tsunami, e.g. UK p56.8, “They’ve been blaming the bombs for upsetting the ecology, whatever that is…”)

- The US edition rearranges some of these scenes; Bocker initially conducts a press conference to summarize his ideas, and takes questions. Calling it an invasion, he discusses HG Wells explicitly, but speculates that if even the invasion wasn’t initially hostile, it’s turned hostile now. Then, the US edition continues with a much shorter interview with Matet, and shorter meeting between Mike, Phyllis, and and Bocker. Six full pages of the UK edition at the end of Phase One are omitted in US.

Phase Two

- Some time has passed. Mike and Phyllis set off early one morning from London, heading for a cottage in Cornwall (establishing that they have a place to go to outside London). They plan to write for a few weeks and then return to London. There’s news that a Japanese liner has sunk, near the Mindanao Trench, and how it went down without warning, in one minute. Next day explanations focus on the issue of metal fatigue, of some specific alloy used in this one ship.

- One night their friends Harold and Tuny show up at the cottage. As they eat they titter about the metal fatigue idea. Tuny especially; you can’t believe official explanations. She goes on about how Bocker must be a tool of the Russians. Just like they tried with flying saucers. How the government is playing up the metal fatigue story to avoid taking action against the Russians. Talk in town echoes the official theory. The story is affecting Harold’s shipping business. What’s really going on? [ This entire section, from 81b to 88b in UK, omitted in US. ]

- Later, the Queen Anne (a large passenger liner) is lost at sea. Devastating news. Mike gets a call from work demanding a half hour story on the invasion menace, to ward off growing anger about the Russians. He works until five in the morning; they visit bars in Falmouth to hear the latest rumors; then they head back to London, just as news of two more ships lost. [ Most of the middle of this is cut in US ]

- Americans decide to bomb the Cayman Trench. Everyone listens live to the radio broadcast of the event, and hear the announcer say that two ships have blown up; others in the flotilla flee, as the bomb is set to go off 5 miles down… he prattles on in panic… until he’s cut off.

- Arguments stop; everyone is convinced there is a real menace. Governments agree to cooperate. Panic hits the markets.

- An international conference is held in London to discuss counter weapons. Different delegates speak. Russians claim credit and won’t deal with capitalist war-mongers, and withdraw.

- Reports come in from Saphira, a remote Brazilian island, where a visiting ship finds the island deserted. And from April Island, populated by Indonesian malcontents. Responding to an escapee, an official ship arrives. The landing party finds tracks in the beach sand, as if from objects coming ashore. Everything has a coating of slime. No one is found. They find a handful of survivors, on a hilltop, who say the sea isn’t safe, claiming they were attacked by whales, and jellyfish.

- This news seeps out, just as officials suggest avoiding deep seas altogether — and two more ships are lost. [ Long para about how various UK newspapers differently report the news, cut in US ] Mike phones Phyllis, at their cottage, and summons her back to London. Their boss at the EBC wants to send them on an expedition to gather photos, evidence.

- So Mike and Phyllis come to the island of Escondida, where they sit on the beach for five weeks, waiting for something to happen, as reports come in of visitations on nearby islands.

- — And then we come to the biggest action scene in the book, the second of three. One night there’s commotion on their beach. Phyllis won’t let Mike leave their room, but they see and hear people scream, run. They hear a scraping sound. They see a ‘sea-tank,’ like half an elongated egg. Two more follow. A priest ventures forth, and disappears. Then the objects extrude spherical things on necks (cilia), expanding. They float into the air, then they bloom into filaments that spread over the town. One grabs Phyllis, and strips her arm of skin, before Mike drags her back inside. Outside the cilia drag people toward the bubble. A plane flies overhead, fires at them, and they withdraw.

- The survivors gather next morning. They abandon the town, covered in slime. They got a sample of a tentacle. They conclude the devices were on a specimen gathering expedition, like shrimping. They got photos.

- Back home Mike reads The Beholder, with a scandalous story about Bocker’s trip, expressing sympathy but rejecting cause for alarm, as if Bocker is trying to put something over on them. Rejecting the idea to embattle the west coast of Britain.

- More newspapers become scornful. Mike and wife finish their scripts, and head for their cottage in Cornwall, where Mike discovers that Phyllis has built an arbor (arbour in UK). They settle in. In the outside world, cargo is now shipped by air, raising the cost of living by 200% and upsetting the economy. Clipper ships are built. Raids by sea-tanks continue around the world. Phyllis wonders why the government won’t let people have arms. She’s tired of the humbug and propaganda. Government action will be too late. How many people must die…?

- They visit a doctor; apparently Mike’s been talking in his sleep. (The suggestion Mike is subconsciously suicidal is mostly removed in the US edition.) He’s referred to a man in London, and sent to Yorkshire to be away from everything. For six weeks.

- More reports come in of attacks around the world — Spain, Australia, Chile. Then Ireland. Mike returns to London, joining Phyllis to check out the attacks in Ireland. Minefields are installed along beaches to kill the “coelenterates” and warn townspeople.

- Then the attacks stop, as if giving up. Bocker warns against complacency. Humans still must strike back. Now he thinks no peace was ever possible. They must exterminate. Before they strike again.

Phase Three

- Mike and Phyllis are out in a dinghy, night, in a flooded London. (This is the third action scene.) The river ahead is blocked by locals; they take refuge in the top floor of a submerged house. He hears bumps in the middle of the night, sees a boat drift pass the house. Mike chases it, finds a dead woman inside. He secures the boat and returns to their refuge; perhaps the boat can get them to Cornwall?

- (This entire section, a flash forward of eight pages about trying to leave a flooded London and finding the boat, cut in US.)

- Here US edition begins, continuing the chronology of Phase Two: After six months the next method of attack is apparent. It began with heavy fogs in many areas. The Soviets note a large patch of persistent fog near the pole, in their territory, and accuse the Americans. Greenland reports increased water flows. Icebergs. Greenland glaciers calving.

- The public finds all this merely curious. Some still suspect the Russians. News comes of ice breaking up in the Antarctic. Then one of the papers publishes an article by Bocker, warning that this is latest method of attack — melting of the arctic ice. The effect will be to raise sea levels, perhaps by 100 feet. Sea level has already risen by two and a half inches.

- Alarmed, Mike and Phyllis visit Bocker, who feels demonized. Phyllis says his conclusion was anti-climactic — two and half inches! To the public, that will sound like nothing, another exaggeration of danger by authorities.

- [[ Here the book anticipates climate change, of course, but in general the entire novel is about resistance to an existential threat. In the UK edition, at this point, we’ve already seen that the worst has happened, with a flooded London. The US edition by omitting both that flash-forward and the introduction, leaves the outcome of the alien invasion open-ended in a way the UK version did not. ]]

- A rich comment, p201.6, about how the Government doesn’t want to “alarm people unnecessarily” and about the Americans: “Same attitude — if anything a bit more so. Business is their national sport, and, like most national sports, semi-sacred.“ [[ Re-open the economy! ]]

- What can be done? Salvage art and important people? Personal advice: find a self-sufficient hilltop and fortify it.

- But response is slow. A Bomb-the-Bathies movement begins. Spring tides overflow the Embankment. Water trickles through sandbags until they collapse, flooding central London.

- There’s a mention of how the US suffers trouble along its southern coasts. Mike and Phyllis agree to stay at their jobs; the EBC leases two top floors of a department store.

- Eventually orders are given to evacuate London. Evacuees encounter resistance, e.g. roadblocks, in outer areas. Order breaks down. Looting begins. The government moves to Harrowgate. Bombing is discussed.

- A year follows. Things decay, armed bands rove, gangs fight. The government takes over radio. Only a few remain by summer. Tides reach 50 feet. Mike and Phyllis contemplate heading north, but are advised to stay. Winter comes; London is mostly deserted. They carry guns. They worry about food. Water reaches 75 feet, and floods their basement.

- In May, Phyllis wants to retreat to the cottage. They find a dinghy, and head up-river. Then they’ve found a motor-boat [ This is where the flash-forward would go, greatly condensed and put into chronological sequence in the US text ]. Now they head down-river. In a month, they reach their cottage, emptied of all supplies. But remember Phyllis built an arbor? She stocked it with food!

- Sea levels rise and their cottage on its hill becomes an island. Their radio goes out. They live off their stocks and are unbothered.

- There are more sea-tanks. It gets cold. The sea freezes. They decide they’ll need to leave.

- At this point the endings of the two versions diverge. UK ending, in 4 ½ pages: On May 24th, a man rows up with news — their names are on the radio, they’re wanted by a Council for Reconstruction. In London. Bocker’s been on; the water has stopped rising. Between 1/5 and 1/8 the world population has died, most of pneumonia. Bocker claims ultrasonics will kill them underwater. The Japs did it! Working on it four or five years. Jelly washes to the surface, that’s all. The man departs, and Mike and Phyllis contemplate, how once the waters drowned the plains; they’ve been here before. (A Biblical reference, I suppose.)

- US ending, in 10 pages: As they prepare to leave, on May 4th, a helicopter arrives, hovers, lets a man down a rope ladder — it’s Bocker. He explains. “This isn’t Noah’s world”; they’ll recover. Perhaps 5 million have survived, of 46 million (in Britain). They will rebuild. There are jobs for them — building morale. He explains how they’ll build small radios, drop them from the air, begin reorganizing. Bocker explains about the ultrasonics. And there are reasons to expect the climate to improve. Phyllis feels there’s reason to live. Again the line about the plains and the water. The copter returns and takes Bocker away.

Concluding Thoughts

So the UK edition ends with the Deus Ex Machina being described second-hand; the US improves this somewhat with the unexpected appearance of Bocker on their cottage-island to explain developments more completely.

Still, the gist of the ending is… the threat simply goes away. It’s defeated without ever learning where the aliens came from or what they were trying to accomplish.

Copyright page of the Ballantine 5th printing, December 1977. (Click to enlarge.)

Finally, to return to the opening theme: I suspect, without having an easy way to research this, is that it was more common than most readers realized for there to be differences, sometimes substantial, between UK and US editions of some books. Via SFE’s annotations, this was apparently true of most of Wyndham’s major novels. Was it true for Clarke in the 1950s? Ballard in the ’60s? Only wondering; I have no evidence either way. And I suspect the publishers never tell you. Certainly Ballantine’s copyright page gives no clue about the substantial difference in the texts of the two versions of this novel.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

Very interesting article Mark. When John posted his Out of the Deeps article some time back it inspired me to read my Kraken Wakes, which I really enjoyed, only kicked myself I had left it gathering dust on my shelf for so many years.

Can’t really decide re the Rationale bit. It did tend to damp down the suspense a hit, kind of that old chestnut about TV series “They can’t die because they have to be here for next week’s episode”.

Thank you, Mr. Kelly.

I had no idea the differences between the two books were this substantial. Time for a reread.

As you say, an academic issue, but nevertheless endlessly fascinating to some of us lost souls! Thanks!

Wow, I remember looking at this a dozen times on my dad’s bookshelf but never cracking it. I’ll have to look into it because Triffids is triffic.

News to me! I know I read the US edition, but now I do have the UK e-book, so time to re-read.

Are you familiar with the radio drama versions? There is an excellent BBC version as well as a longer and drier CBC version. Both are worth hearing.

I don’t remember the exact details, but there’s an explanation for why this happened in Amy Binns’ “Hidden Wyndham”

Thanks for the comment, Charles. Actually I ordered the Amy Binns book before I did my post, and looked up the titles of these two books, but didn’t see an explanation. I admit I didn’t read through the entire book. Perhaps the explanation is there somewhere?

As I said elsewhere, discovered the differences when I picked up a copy of the UK edition at a convention, read it through. Apparently there are also differences between the UK and US editions of DAY OF THE TRIFFIDS.

This is good Cold War sci fi.lit. Western democracies threatened by some unseen ,foreign power.Note,the scientific heroes are the Japanese under the influence of western powers—remember this book was written only eight years after the end of WW2.Those wily untrustworthy Russians only serve their own ends and the Chinese are inscrutable . Good stuff ,right up there with the walking plants.

The reason that Wyndham’s early novels have different US and UK editions is that he had two sets of literary agents for the two markets. The US agent selling to US publishers was the same agent he used for his early si-fi magazine short stories. When he needed a UK agent to sell his grown-up novels he kept his US agent due to loyalty and friendship.

Both the UK and US publishers edited the novels (or asked for changes) to suit their markets – hence the differences.

Well I always assumed it was something like that. What struck me, when I revisited those books, was how the US edition implied it was a simple reprint of the UK edition. There was nothing about “adapting” it for the US audience or anything like that. But then, as I think I suggested, that was probably done for most books in the ’50s, and for all I know even today, when novels are published in both the US and UK.