Humanity Uplifted: Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave

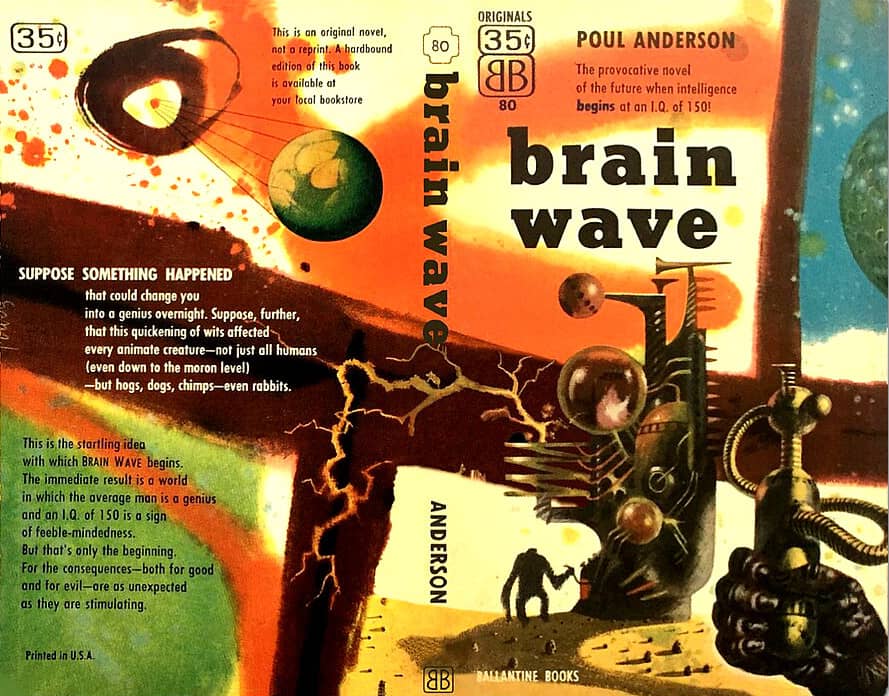

Brain Wave by Poul Anderson; First Edition: Ballantine Books, 1954

Cover art by Richard Powers

Brain Wave

by Poul Anderson

Ballantine Books (164 pages, $0.35, paperback, June 1954)

Cover by Richard Powers

Poul Anderson was a prolific writer of both science fiction and fantasy from the late 1940s to his death in 2001. He was especially known for a couple space opera series, one about the Psychotechnic League and others about Dominic Flandry and Nicholas Van Rijn (I have not read any of these). But his best novels, reputedly, were his singletons, like Brain Wave (1954), The High Crusade (1960), Three Hearts and Three Lions (1961), and Tau Zero (1970), and later works like The Avatar (1978) and The Boat of a Million Years (1989), from decades when everyone’s novels got much longer.

Brain Wave was Anderson’s third novel, after juvenile SF Vault of the Stars in 1952 and fantasy novel The Broken Sword earlier in 1954. The first part of Brain Wave appeared in Space Science Fiction in 1953, but the magazine went out of business before serializing the remainder.

I reread this book recently not to extend a series of reviews of first — or almost-first — novels, but because I wanted to revisit its striking premise. I think I’ll revisit Tau Zero soon, for the same reason.

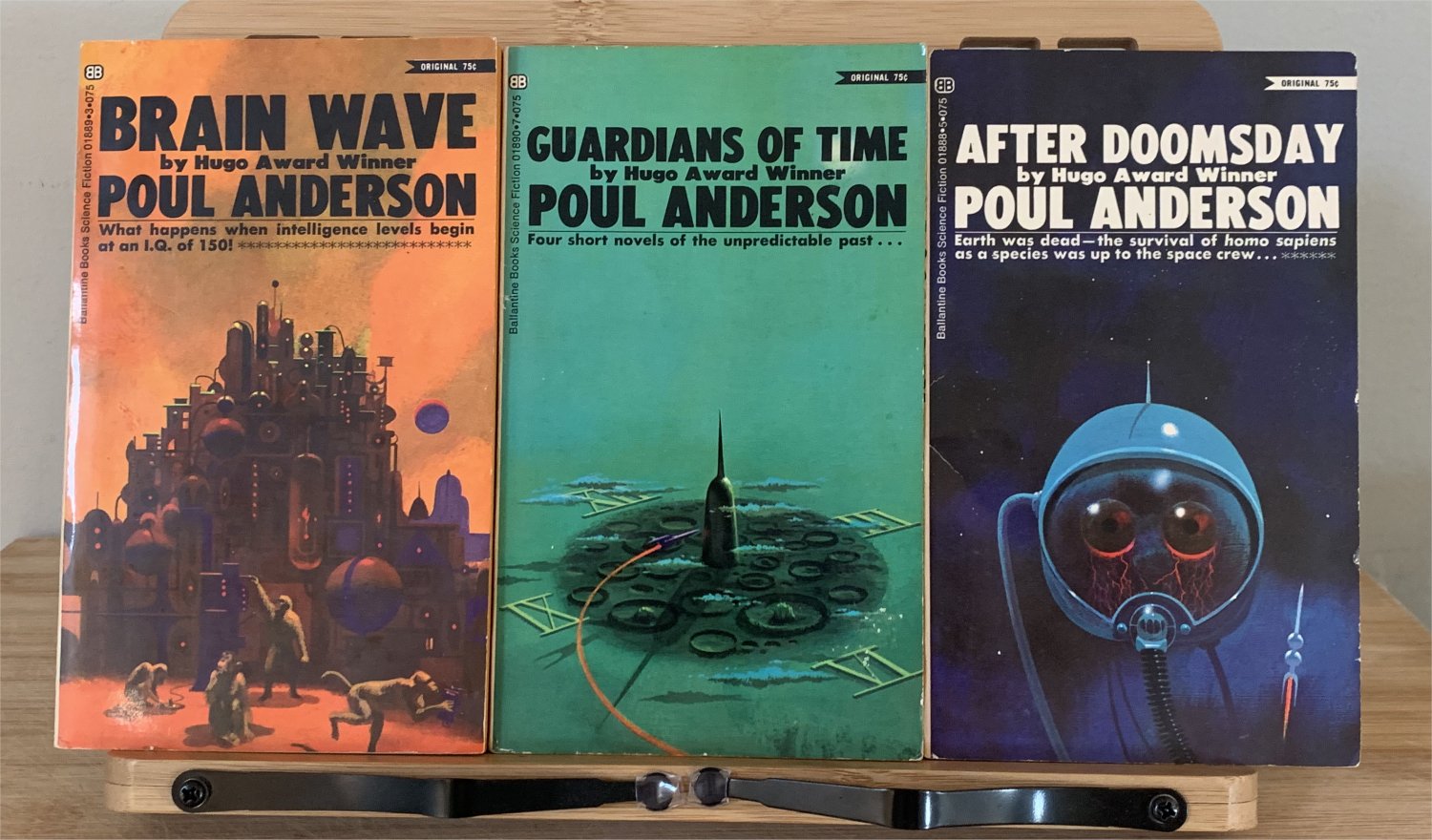

I remember this book’s premise even though not having read the book since… literally 50 years ago, in April 1970, in the triplet of Ballantine reprints with matching cover designs and art by Paul Lehr (photo below). The premise is this: something happens to cause, all over the world, both people and animals to become smarter. Ordinary people become geniuses.

Of course, I don’t remember plot details over 50 years, and often not even the broad strokes of the plot arc. I don’t have an eidetic memory like Isaac Asimov did! And that’s why I’m rereading many of these classic novels. Every time I pick up a book (whether fiction or nonfiction), I try to pose to myself questions about what I expect and what I expect to be answered, if possible, given the book’s premise. So with this book’s premise, of course, you are curious to know, so what happens? How does increased intelligence change the world? What’s the cause? Does it last? At the risk of spoiling some significant results, I’ll follow my usual pattern here:

Gist

Humans and animals all over Earth become super-intelligent; ordinary people perceive solutions to problems that have plagued them; animals learn how to break out of their cages. Society crumbles, because it’s not needed. A minority cabal who thinks life was better before the change tries to install an “inhibitor” field over the Earth to reverse it, but — SPOILER — it fails.

Take

This is a remarkably concise and sophisticated take on the premise of how advanced human intelligence would play out culturally. Intelligence doesn’t overcome other features of human nature. In its conclusion, it’s a prime example of how science fiction depicts such change as progress, in contrast to the theme of thrillers (e.g. the novels of Michael Crichton) that presume that scientific advances are dangerous and must be defeated.

Summary with Quotes and [[ Comments ]]

2018 Open Road trade paperback edition of Brain Wave by Poul Anderson;

cover design by Mauricio Diaz. (Click to enlarge.)

The novel alternates scenes set on a farm (somewhere in the Eastern US), and scenes at in a scientific institute in New York City, whose wealthy benefactor, Rossman, is the same guy who owns the farm. Page references are to the 2018 Open Road trade paperback, edition, shown here.

- The first of 21 chapters sets the stage, at a rural farm: A rabbit breaks out of its trap. Archie Brock, a farm worker digging stumps, has a sudden appreciation for how far away the stars in the sky must be. And an unnamed boy, in the nearby town, extrapolating from his algebra homework, gets halfway to differential calculus.

- Immediately we are exposed to an Anderson trademark: he was given to evocative prose, pastoral passages verging on the purple:

The moon rose higher, swinging through a sky full of stars. An owl hooted, and the rabbit froze into movelessness as its wings ghosted overhead. There was fear and bewilderment and a new kind of pain in the owl’s voice, too. Presently it was gone, and only the many little murmurs and smells of night were around him. And he sat for a long time looking at the gate and remembering how it had fallen.

The moon began to fall too, into a paling western heaven.

- Chapter 2 introduces us to Peter Corinth, a scientist in New York, who as he gets ready for work realizes he has a sudden insight into a technical problem at work. His wife Sheila, instead of picking up a mystery novel, picks up [Joseph Conrad’s] Lord Jim instead. Peter’s neighbor Felix Mandelbaum mentions having an idea for a new reorg plan. The elevator operator wonders about taking a course.

- Corinth heads to work at the Rossman Institute. (Rossman is the wealthy benefactor of the institute, who owns the farm.) His staff there have some new ideas. He has lunch with coworker Nathan Lewis about how everyone is jumpy today, and full of ideas. What’s going on? Something cellular? No, some of the instruments are measuring slightly different than the day before. Electro-magnetic phenomena have changed…!

- Chapter 3: On the farm, most of the hens have escaped the henhouse. Archie tries to hitch a horse to a plow, but the horse deliberately breaks the plow. One of farmhands swears he saw a pig open a gate. They realize, somehow everyone, even the animals, are getting smarter. Archie, who’d always considered himself a bit dim, feels it in himself. He goes to talk to Mr. Rossman, who happens to be on site that day; they both feel it. Rossman says, pages 32-33, “I’d always imagined myself as a quick, capable, logical thinker. Now something is coming to life within me that I don’t understand at all. Sometimes my whole life seems to have been a petty and meaningless scramble… ”

- Chapters 4 and 5 open with newspaper headlines, as the effect is worldwide, e.g. “PRESIDENT DENIES DANGER IN BRAIN SPEEDUP” and “Communist Government Declares Emergency / NEW RELIGION FOUNDED IN LOS ANGELES” and “Sawyer Proclaims Self ‘Third Ba’al’ — Thousands Attend Mass Meeting / FESSENDEN CALLS FOR WORLD GOVERNMENT.”

- At the institute Corinth and Mandelbaum discuss how IQs are increasing. Yet — here’s the first indication that Anderson is expressing a thoughtful consideration of all aspects of human nature, and not just enhanced intelligence per se — there is discussion about the flaws of IQ tests:

If you’re a Caucasian of West European-American cultural background. That’s who the test was designed for, Pete. A Kalahari bushman would laugh if he knew it omitted water-finding ability. That’s more important to him than the ability of juggle numbers. Me, I don’t underrate the logic and visualization aspect of personality, but I don’t have your touching faith in it, either. There’s more to a man that that, and a garage mechanic may be a better survivor type than a mathematician.

- And then follows some speculation (on rather thin grounds it seems to me) about the how the whole solar system has come into, or has left, some kind of force-field, that has for millennia been inhibiting native intelligence. They wonder what will happen as people become smarter: Page 44:

Basic personality does not change. And intelligent people have always done some pretty evil or stupid things from time to time.

- Chapters 6 and 7 describe further changes in the city. Many flee to the country; others riot; people with ordinary, dull jobs refuse to do them. The scientists at the institute come to speak in a clipped manner, meaning clear by context and implication. Emotions are more intense. People are smarter, but not necessarily more sensible [[ This reflects how in our own time even some smart people can be sucked into conspiracy theories or crazy religions; because smart people are especially good at rationalizing conclusions they’ve reached on emotional grounds. ]]

You’ve taken millions of people who’ve never had an original thought in their lives and suddenly thrown their brains into high gear. They start thinking—but what basis have they got? They still retain the old superstitions, prejudices, hates and fears and greeds, and most of their new mental energy goes to elaborate rationalization of these. Then someone like this Third Ba’al comes along and offers an anodyne to frightened and confused people…

- Two months after “the change” Archie heads into town, where most stores are closed, while a man at the A&P describes how things have changed, with little need for formal government, though it’s not exactly socialist, p79:

That’s hardly the right label for it, since socialism was still founded on the idea of property. But what does ownership or property actually mean? It means only that you may do just what you choose with the thing. By that definition, there was very little complete ownership anywhere in the world. It was more a question of symbolism.

- Archie is invited to join this community, but declines, returning to the farm.

- Supplementing the earlier headlines are occasional sidebar scenes showing effects around the world: An African witch doctor plotting some kind of revenge, in collaboration with now-smarter chimps and elephants; Red Army troops use a priest, and a “sensitive” (telepath, of which there are some 10,000) to help Ukraine. Later in Chapter 14, a Chinese village, where a stranger arrives offering to teach them not to be cold; it’s about use of the mind.

- Felix Mendelbaum works his way into city government, becoming first a fixer, then the city’s chief administrator. The institute works on developing an inhibitor field. They reflect on science and art: “Scientists—like artists of all kinds, I suppose—have by and large kept their sanity through the change because they had a purpose in life to start with, something outside themselves to which they could give all they had.” (p96). They speculate about building an FTL drive, and how they now know that some telepathy is possible.

- Meanwhile Corinth’s wife Sheila is not handling the change well; she’s suffering a nervous breakdown. Corinth has dinner with Helga, a staff member at the Institute. [[ I noticed about this point that Anderson routinely refers to female characters, once they’ve been introduced, by their first names, and male characters by their last. Except for Archie, the dimwit. At the same time, there are only two female characters in the book. ]]

- Chapter 11 is a kind of sidebar scene (it has no influence on the outer story), as Rossman and Mendelbaum sit in the lab wondering if their defense will work. They’ve calculated that the Soviets are about to make a last-ditch attack on the US. A device has been mounted at the top of the Empire State Building, a force field. As they wait they wonder what people will do, sent back to an animal plane. Is it the end of science, of arts? Or does the universe await? (On prayer, p107.3: “If there was to be a religion in the future, it could not be the animism which had sufficed for the blind years.”) The moment comes; four bursts (nuclear bombs) go off; the shield holds.

- And soon a starship is under construction.

- Meanwhile, at the farm, some hands have packed up and left, while various loners find refuge there, including an imbecile. Archie realizes he needs to slaughter a sheep, and wonders how the other sheep will react, if they see the slaughter. He reflects on how animals react to this change, 124b:

But the other beasts had lived in a harmony, driven by their instincts through the great rhythm of the world, with no more intelligence than was needed for survival. They were mute, but did not know it; no ghosts haunted them, of longing or loneliness or puzzled wonder. Only now they had been thrown into that abstract immensity for which they had never been intended, and it was overbalancing them. Instinct, stronger than in man, revolted at the strangeness, and a brain untuned to communication could not even express what was wrong.

- And then the starship is done and Corinth and Lewis are out in space on its maiden voyage. Abruptly, something changes; they realize they’ve hit the edge of the field! (Re-entering it, apparently.) Immediately they feel their new intelligence fading…

- Sheila undergoes an extensive psychiatric evaluation, and is put up in a beach house, where she waits as the deadline for the starship’s return passes. (There’s a mention here of general semantics, which I keep seeing references to in works from this era, but have only the vaguest understanding of; p140.9: “The triumphant discovery of the obvious” says Sheila).

- Corinth and Lewis manage to turn their ship around — the FTL drive allows them to easily do that — and exit the field, their intelligence returning. And so they survey Earth-like planets, surprised to find so many, 14 of 19, inhabited by intelligent life. But perhaps significantly, none seem more advanced than humans were. Is there some limit on intelligence? Why did all this happen?

- [[ Now here I thought there might be a suggestion that humanity had been deliberately suppressed? Where did this force-field come from, after all? If this were a Campbellian story, there would have been some malevolent force beaming the field over Earth to keep humans from reaching their full potential, which naturally would have been superior to all these other intelligent races… as the situation now seems to be the case. But Anderson doesn’t go there. ]]

- Meanwhile back in New York Mendelbaum gets reports from “Observers” — undercover government spies, apparently — of supplies going missing, as if some secret project is underway.

- Summer comes. Sheila, having never recovered from or adjusted to the change, visits in the Institute, walks through Pete’s lab, where early equipment for doing electroshock therapy still sits. Sheila waits until Helga and the others leave for lunch, then hooks herself up to the equipment and turns it on — feeling PAIN!

- Months late, the starship returns. Landing, Corinth learns his wife… isn’t dead. Rather her self-treatment had the effect of reverting herself to her original, pre-change state. He visits her in hospital; she’s happy, but she tells him he’s not the Pete she knew.

- The climax of the novel approaches. On a Pacific atoll — whose history of its original Polynesian settlers and how white men came and overtook them, is told in two pages that demonstrate Anderson’s skill at evoking big history and broad historical trends — a group of international people meet, page 180: “A Russian officer, a Hindu mystic, a French philosopher and religious writer, an Irish politician, a Chinese commissar, an Australian engineer, a Swedish financier.” They’ve come here to address a “yearning” for the past, and we gather they are about to launch a field generator into orbit, which will re-inhibit mankind into its former state.

- But — another ship, a starship!, arrives overhead, bringing Felix Mendelbaum, Pete Corinth, and Helga. This more advanced ship uses weapons to destroy the launch ship, and Mendelbaum declares the others insane — “If the delusion that you few have the right to make decisions for all the race, and force them through, isn’t megalomania, then what is?” p184.2

- Here’s the thematic core of the novel, played out in dialogue. Is there progress, or does humanity need to cling to a glorious past?

- The Hindu replies: “The world has been blinded. It can no longer see the truth. I myself have lost the feeble glimpse of the ultimate I once had, though at least I know it was lost.”

- And Mandelbaum replies, “What you mean is that your mind’s become too strong for you to go into the kind of trance which was your particular fetalization, but you still feel the need for it.”

- The Frenchman complains, “Are all the glories man has won in the past to go for nothing? Before he has even found God, you will turn God into a nursery tale? What have you given him in return for the splendors of his art, the creation in his hands, and the warm little pleasures when his day’s work is done? You have turned him into a calculating machine, and the body and the soul can wither amidst his new equations.”

- Mandelbaum replies: “The change wasn’t my idea. If you believe in God, then this looks rather like His handiwork, His way of taking the next step forward.”

- And further: “The trouble with all of you is that one way or another, you’re all afraid to face life. Instead of trying to shape the future, you’ve been wanting a past which is already a million years behind us. You’ve lost your old illusions and you haven’t got what it takes to make new and better ones for yourselves.”

- And further: “Sure, all our past has been stripped from us. Sure, it’s a terrible feeling, bare and lonely like this. But do you think man can’t strike a new balance? Do you think we can’t build a new culture, with its own beauty and delight and dreams, now that we’ve broken out of the old cocoon? … Now we have a chance to get off that wheel of history and go somewhere — nobody knows where, nobody can even guess, but our eyes have been opened and you wanted to close them again!” (p186)

- [[ These trials between tradition and comfort on the one hand, and exploration and reality on the other, are not new. Anderson does the debate justice. ]]

- And we learn, in a much more emotional exchange, that Sheila will be sent to a “moron colony,” where those like her who’ve gone insane trying to adjust can live together.

- The final chapter is set back on the farm, where the book opened. Anderson’s pastoral prose:

Autumn again, and winter in the air. The fallen leaves lay in heaps under the bare dark trees and hissed and rattled across the ground with every wind. Only a few splashes of color remained in the woods, yellow or bronze or scarlet against grayness.

- The human community at the farm has expanded, and there’s even a girl there, Ella Mae, but she’s not suitable for Archie, who still feels lonely. An airship arrives! It brings Nat Lewis, an associate of Rossman’s, and he wonders if Archie has a wife…? No. So he explains to Archie that “their kind” will not remain on Earth; Archie’s kind will be left to inherit it. And a new member will come to his farm… The new member later arrives. Sheila. No last name, just Sheila.

March 1970 Ballantine reprint editions of three Poul Anderson books,

with cover art by Paul Lehr:

Brain Wave (first published 1954), Guardians of Time (1960), and After Doomsday (1962). (Click to enlarge.)

Conclusion

This is a sophisticated and relatively ambitious novel from a young writer who did much later relatively unambitious work (deriving this conclusion in part from SFE). Except for certain sexist attitudes, it holds up well, and its theme about tradition vs. progress is as relevant as ever.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Arthur C. Clarke’s Prelude to Space. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

Great review! Thanks for all the effort you put into these.

This is a fun book. I’m not sure if I would have read it as a youngster, had it not been included in the massive Boucher collection A Treasury of Great Science Fiction.

Personally, I enjoy Anderson’s brawling Planet Stories period, but I can see why it wouldn’t appeal to the refined tastes of the SFE.

His big series are very uneven in quality, which is rough for people who feel like they have to read the whole series or nothing. The Psychotechnic League stories are almost unbearably lecture-y–not sure any of them are on my reread list. But Satan’s World is a ripping yarn about a rogue planet that becomes the flashpoint for a struggle between two very different starfaring civilizations. It’s part of the van Rijn/Falkayn sub-series. The other sf book by him that I really like is A Circus of Hells. It’s a spy story–a chess story–a novel of psychological struggle–wonderful worldbuilding–and it’s weirdly and lumpily constructed.

And, of course, The Broken Sword is one of the great heroic fantasies.

[…] and awarded sf/f writer, Poul Anderson, over on Blackgate.com, Mark R. Kelly provides another of his lovingly detailed re-reads of a sf/f classic, in this case, Mr. Anderson’s early novel about an intelligence booster affecting all life on […]