Viewpoint Intimacy Through a Third Person Lens

|

|

|

Cordelia’s Honor by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen 1996, cover by Gary Ruddell), The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison (Tor 2014,

cover by Anna Balbusso and Elena Balbusso), and A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine (Tor 2019, cover by Jaime Jones)

Since quarantine has brought an unexpected windfall of time for me, I’ve been beta-reading more than usual, and from sources beyond my immediate network of writer-friends. With these new novels, however, I’ve noticed this trend of a lack of intimacy with third person viewpoint characters.

I’m not sure if this is a discomfort with diving deeper into their character’s viewpoint, not knowing how to deep-dive into PoV, or taking the “show-don’t-tell” adage a step too far, to the point where the prose only “shows” action and all moments of interiority and reflection are seen as “telling.”

Or perhaps it’s that some writers watch more films, or play more video games, than they read, and recycle techniques borrowed from visual media that don’t have the same impact in prose? This is not to disparage visual and/or interactive entertainment, nor writers who learn how to tell stories in that media. However, visual media uses a different skill-set to convey emotion, and there are things that can be done with prose that can’t be done as well in film.

Whatever the root cause, I’ve read multi-viewpoint novels where the writers specifically stated that the plot was deeply character driven, and yet, for the life of me, I couldn’t tell you anything about the characters that wasn’t directly tied to the plot. It’s as if the writer feared to bog down the narrative with character backstory, either as a result of excessive edits or an unwillingness to include it in the first place. By the end, all that was left was what was introduced in Chapter 1. The characters had no past, and their only future derived from events in the story. I felt so removed, like I was watching things unfold from a distance, and while the plot escalated and had the necessary dramatic beats, I simply didn’t feel anything. I wasn’t experiencing, I wasn’t sinking into the prose and being transported.

While I can recognize the problem and describe the effect (or lack) it has on me, I honestly have no idea how to outline a solution in a way a writer could actionably apply. It isn’t like grammar or spelling, where there’s a generally accepted “standard.” I know it’s missing, I can point it out, but I have no concrete approach to retrofitting emotional intimacy with a viewpoint character into a completed novel.

Since I can’t define how to fix it, I thought I could at least present a few examples (within the genre range of science fiction and fantasy) of writers whose writing does facilitate that deep connection between me and the viewpoint character: Lois McMaster Bujold, Terry Pratchett, Robert Jackson Bennett, Katherine Addison, Arkady Martine, Tamsyn Muir, Scott Lynch, S. A. Chakraborty, George R. R. Martin — these are just ones I see glancing at my shelves.

Each has written third person viewpoint novels with such a depth of character, an intimacy of narrative scope, that I understood not only who the character was, but who they could become. A three-dimensional character, I argue, is not only one that has an almost physical presence on the page, but one that creates the illusion of time — through backstory, complex emotional landscapes, opinions and goals, defeats and successes.

|

|

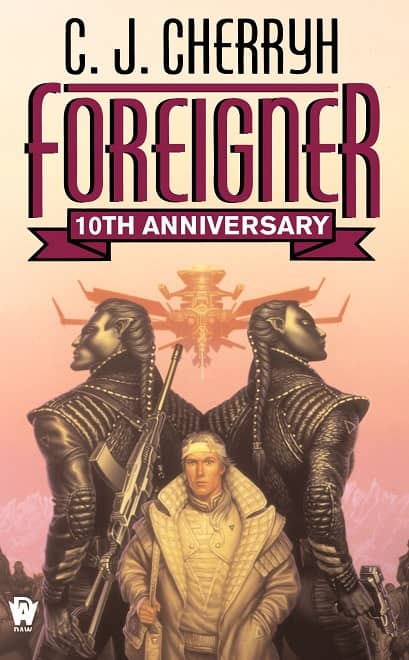

The Priory of the Orange Tree (Bloomsbury 2019, cover by Ivan Belikov), and Foreigner (DAW 1994, cover by Michael Whelan)

There is a caveat: not all stories need be told from a deep, intimate dive into the mind of their point of view character. Some stories are served by a more distant, even dispassionate narrative style, such as Samantha Shannon’s The Priory of the Orange Tree or the opening of C. J. Cherryh’s Foreigner, where the scope of the narrative’s voice implies the scope of the story itself, and intimate third person would be a limitation. This, however, requires the narrative voice to carry the brunt of the reader emotional engagement.

Writing that speaks and connects to me may not do so for you. Not everyone experiences fiction the same way (and wouldn’t it be a bland world if we did?)

So on that note, I encourage writers to seriously think about those books where you felt so deeply immersed in the viewpoint character it was as if your heart beat in tandem with the prose, where the third person narration infringed so closely on first person, you forgot the pronoun being used.

Let those writers be your guide.

A Chicago native, R. J. Howell has a BA in Fiction Writing and an MFA in Creative Writing: Popular Fiction. Her fiction has been published in Arsenika Issue 6 and Beyond the Stars: Rocking Space, among others. You can find her online at rjhowell.com and at her blog.

Great piece! Something I’ve realized lately, as I’m working on my latest novel: The more you have your CHARACTERS reflect, the more your READER will reflect. In other words, the more time your viewpoint characters spend thinking about themselves, their ideas, and their past experiences, the more the reader will come to know and understand this character. A good example from the cinematic world is Quentin Tarantino–he’s known for two things mainly: 1. Lots of action/violence and 2. Lots of extended conversations that go on “tangents” that end up humanizing his characters. So when Vincent Vega spends five minutes talking about Burger Kings in France, he’s not just “going on a tangent,” he’s displaying character. So in my latest work, I’ve been trying to provide for reflective time for my characters–one of the things p-o-v characters MUST do is THINK. “Reflecting” is a better word. Some authors have characters that reflect SO much, I end up losing interest. Other authors have NO inner reflection from their p-o-v characters, which also makes me lose interest. As with so many things in writing (and other arts), the key is to strive for a proper balance of reflective prose and action-based prose. Give your characters plenty of time to reflect/think/muse/ponder/sulk/cogitate/remember/dream…then later when they “spring into action” they will seem more realistic and the dangers they face will seem more convincing. As characters reflect more, readers reflect more, and the whole experience gets deeper. Cheers!

John,

Very true. Character reflection is just as much a part of narrative pacing as action and dialogue, and can be used to not only slow down a scene, but also slow down the reader, allowing details and concepts to be fully digested. On the one side, it deepens the reader’s understanding of the character, and on the other, allows those moments of character change to feel appropriately life-changing and profound. Good point about Quentin Tarantino. When I was researching how to deepen dialogue, I studied Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, analyzing the conversations and how dialogue can be used to characterize the speaker, characterize the listener, develop the world, and lend that air of realism, of true experience, within a fictional context. And I agree entirely with the need for balance. Balance is key. Too much of one breaks the “narrative dream” and reminds me I’m reading. Too much of the other, same problem. A just-right balance that oscillates between the two, and I’m a happy reader. Genre expectations, I think, also play a huge role in this, too. If I’m reading a thriller, I expect little reflection. If I’m reading a romance, I expect pages of reflection. If these are flipped…I admit, I’d struggle as a reader, though I’m sure there’s examples of reflection-heavy thrillers and reflection-less romances.

I think maybe some writers want to appeal to as broad an audience as possible and reckon this is more likely if information about the mc is kept to a minimum (ie, it gives readers of all persuasions room to project their own values onto the character). Personally I prefer the sort of books you describe, although you can have too much of a good thing – I seem to remember Thomas Convenant’s reveries going on for so long that – some ten pages later – I’d largely forgotten the context. Where was he again? What was he doing? What provoked the reverie in the first place?

It’s funny that you should mention Tarantino, John. I was just saying to my brother the other night that ‘Kill Bill’ (not a bad movie per se) marked Tarantino’s transition from scripts that were dialogue driven to scripts that were focussed on visual spectacle.

Aonghus,

There is definitely the flip-side of this, where characters ruminate so long in one room, that you forget there was a room, or that the characters where doing something prior to the ruminating. Too much of one is just as much of a potential issue as too little. It’s finding the balance between them that’s tricky, and even if a writer does find that balance, there’s still the subjectivity of art.

There are characters where the lack of reflectiveness, of any kind of interior life, is the point – Richard Stark’s Parker, for example. His mind is all wheels and gears.

Thomas,

That is an excellent point. While I haven’t read Richard Stark’s Parker novels, I perused the Amazon sample of one (The Hunter), and I tentatively hazard that, based on that sample, it’s the strong narrative voice that’s carrying it, making the need for character viewpoint intimacy moot. It’s also a good point that not all characters are reflective and/or the sharing type when it comes to their viewpoint, and in multi-viewpoint novels, that difference can definitely be used to define/characterize viewpoint characters and differentiate narrative styles.

I admit I haven’t read any of her Foreigner books, but I’ve read some Cherryh books (Heavy Time/Hellburner, Rimrunners and Finity’s End leap immediately to mind) that were from such a tightly-focused third person POV that they felt almost claustrophobic.

Joe,

Admittedly, I’m a newcomer to Cherryh’s books and I’ve just started with Foreigner, so it was on my mind. Also admittedly, that over-arching, epic-proportions narrative style is used primarily in the beginning. It switches to that more almost-claustrophobic tight third person once Bren is introduced. So in a way, Foreigner is an example of both.

During the last couple of decades, I’ve noticed a seeming trend of more and more novels reading practically like screenplays — action, dialogue, action, dialogue, little else, etc.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, I suppose, but yeah, it doesn’t immerse the reader as much into the characters or even the story.

Then again, the likes of Lee Child (for example) are quite popular, so at least a segment of readership must be finding what they’re looking for.

Ty,

That’s very true. Dialogue and pure actions scenes are inherently fast, and the eye zips through them fairly quickly, creating the fast pace of fast-paced thrillers. There might also be more than a little bleed-over from the thriller genre to speculative fiction, which could explain that screenplay-like appearance. Good point!