The Stories We Tell: Bias in Research and Its Effects on Fiction

Hadrian’s Wall, from the ruins of a Milecastle. Image from publicdomainpictures.net.

Good morning, Readers!

Last week, I was watching a lecture on Hadrian’s Wall, as you do, hoping to learn something new about the situation in Britain during the Roman occupation. I did not, incidentally, learn anything I had not already known (if money was no object, I would have a doctorate in archaeology, specializing in the British Isles, and probably a few extra degrees in archaeogenetics and archaeolinguistics. I am fascinated by these things). The lecture did, however, serve as a stark reminder of the frustrating presence of bias that permeates even intellectual pursuits. This lecture, in particular, veered hard towards a Roman bias, something that has been so prevalent in the field I am so interested in, that I’ve often shut books and thrown journals across the room.

The constant referrals to the indigenous Britons as ‘barbarians’ grated on my nerves enough that I had to pause the video and come back to it at a later time. It is, of course, almost understandable. This adoration of the Classical world have long been a part of British identity. Some great pains were made by some early historians to connect the Island of Britain to the classical world, claiming that the island itself was named for Brutus of Troy (In the History Brittonum (c. 9th century), Brutus was a Roman consul, and in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th century treatise on the subject Historians Regum Britannae, Brutus freed a bunch of capture Trojan slaves, became their leader, and eventually came to and settled the island.

This is, of course, tosh of the highest kind. Britain is, near as most can tell, a bastardization of the name of the island as given to it by its original brythonic speakers (whose linguistic descendants can still be found in Wales and Cornwall, and whose language was very closely related to the original language of Gaul (now France)). The island was probably named Prydein or Prydain.

Still, this connection to the Classical world, held up as the gold standard of civilization in Europe even to this day, was responsible in large part for Britain’s attitude at the height of its colonial era. They were the descendants of Classical heroes (likely untrue), and thus the best of Europe. Nay, the world! Or something.

The attitude that Rome, in particular, was the ultimate culmination of European civilization, the peak of perfection, is something that was present in the Middle Ages and is still parroted by casual inquirers and serious academics alike today.

And it’s bullshit, in my humble opinion.

An illustration, depicting Ambrose observing the cause of the continued collapse

of Vortigern’s tower, from a 15th c. manuscript of Historians Regum Britannae.

Look, there’s no denying that Rome, and Greece before it, managed some incredible feats; impressive aqueducts carrying water to sprawling cities, paved roads, indoor plumbing. All these things and more are used as evidence of Rome’s supposed superiority. But we rarely see the same sort of academic adulation spared for the incredible works of the Egyptians, who build pyramids that stretch to the stars, or the gorgeous cities by the Nubian civilization, their predecessor. The stunning cities by the Meso-American cultures – the Olmec, Inca and Aztec empires – are observed with cold interest, admiration for their remarkable achievements and incredible innovations much more subdued. The same breathless awe is not spared for the era-straddling work of incredible mathematical and physical labor that is Stongehenge (construction of this complex began in the Neolithic and ended in the early Iron Age), or the stunning passage tombs of the Brugh ná Boinne (Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth), which are part of a much larger complex.

Indeed, while we’re not at all doubtful of the origins of Greek and Roman achievement, folks have spent a lot of time denigrating the achievements of peoples not from the Mediterranean, proclaiming those natives utterly too uncivilized, too ‘barbaric’ to be responsible for such magnificent works. No. Those were built by giants. Or aliens. Aliens, for heaven’s sake!

Newgrange, a Neolithic corballed passage tomb in the Brugh ná Boinne complex in Ireland. Every

winter solstice, the sunrises to shine directly into the tomb, striking the highly reflective

light stone at the back, and flooding the interior with sunlight. It is a remarkable achievement.

I’m not saying we ought to be downplaying the impact and achievements of Greece and Rome at all. That’s not the point. But I do want to make note of some of the strange blindness that people who so laud these cultures. They cannot see either the faults of their favoured culture, or the incredible contributions of the other cultures that existed before or after or in places other than Europe.

Sure, Rome displayed its might in the conquests of Europe, and Alexander of Macedonia before that. But while those achievements are held up as a symbol of proud achievement, other peoples similarly contesting are denied praise, and labelled barbarians. Where is the worship of the Mongol hordes, whose conquests outclasses Rome even at its height? Can we not spare some admiration for the Ottoman Empire? Why is it that Rome’s conquests were clever and heroic, but when the Gaulish chieftain (the Gauls were Celts, just as the Britons were) Brennos sacked Rome, this feat was not celebrated? No, the Celts, Mongols and Ottomans were then, and now, barbarians at the gate.

And don’t get me started on how poorly we’ve neglected Indigenous American achievements.

As much as conquest, particularly of the Roman variety, is celebrated and admired so, I would also like to remind people that it is monstrous. Julius Caesar, spoke of with reverence spared for few else, was responsible for terrible acts of genocide. The Eburones, for example, were obliterated by Caesar’s own admission. The entire tribe.

Side note: it is likely that individuals did manage to escape and survive, but tribe itself was gone, as many other tribes of the same region (current-day Netherlands) as many of them slaughtered at Caesar’s command as possible.

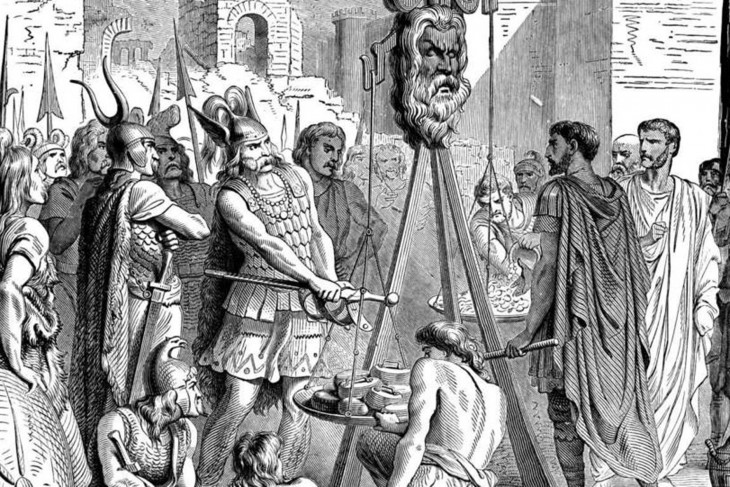

Artist’s impression of Brennos demanding tribute from Rome.

And yes, the Republic of Rome was a democracy. Which is great. If you were a man. For all the credit Rome is given for democracy, little attention is paid to the cultures outside of Rome, and how much better they were for, say, women. Women were permitted to rule (the British queens Boudicca and Cartimandua so prove, and there is ample archaeological evidence of high-status women), participated in battle (as several chariot burials, Viking warrior burials, as well as considerable references to female warriors support), were also judges and mediators (Plutarch mentions their importance during the dispute between Hannibal and the Gauls), and held important religious positions, their number being noted in the scourging of the Druidic sanctuary on the Isle of Môna (now Anglesey). The Brehon Laws of Ireland note that women have the power to divorce their husbands for a whole host of reasons (his inability to sexually satisfy her resulted in the payment of a fine… which I find hilarious), and getting a woman drunk in order to sleep with her was punished severely (clue: because that’s rape).

So yes, Rome was democratic – if by democracy you mean the participation of citizens only, and women were not considered citizens. Very civilized. If, however, you use a different metric, that which considers the involvement of both genders in the running of society, Rome was less equal by far that it’s ‘barbaric’ neighbours. In some ways, more equal than even today.

The deliberate ignorance of the lives and contributions of women is another bias that infects historical analysis.

And don’t get me started on medical contributions. We’re talking about a people who thought strapping fox testicles to one’s head would cure a headache (genuine Roman prescription), and we’ve lost all record of how cultures outside of the Classical world dealt with healing, so we’ve nothing to compare it to.

Orcs, probably on their way to Helm’s Deep. Because the whole species is unthinking in their evil.

All of the ranting about historical bias has a purpose, I swear.

This bias in our academic or intellectual pursuits has far-reaching consequences, showing up in things we might not give much thought to, like the fiction we consume.

The bias against women in the historical record, for example, has lead to a dearth of popular books which feature women as the central hero. It has become so pervasive that any books that do centre women as the hero are unjustly derided as having a ‘Mary Sue’ of a main character. It has led to angry claims that the exclusion of women as affecting the narrative in any meaningful way is entirely ‘historically accurate.’ Which is nonsense. Women and their actions have been central to history, even if acknowledgement of their contributions has not (Boudicca’s rebellion, for example, is completely excluded from a book about the history of Britain that I own. That book was published in 1991. 1991. And they excluded a woman who united three tribes, obliterated an auxiliary, and razed three cities to the ground. A woman who has an entire archaeological layer of blood, ash and bone in the south-east of Britain named after her). Women have fought in wars for as long as men have (even into modernity, and I highly recommend Rejected Princesses for a pretty decent resource about women and their contributions).

The framing of non-Mediterranean cultures as barbaric, a foil to the civilization and greatness of the Classic world is not just inaccurate, it has led to unexamined portrayals of entire cultures as part of a wholly unbelievable binary (this group = good, others = bad), that divides along, dare I say it, racial lines.

Let’s take orcs, for example. In Tolkien’s works, which I still love, orcs are evil creatures. Twisted, hateful barbarians. They’re a race painted with the broadest possible brush; barbarians set against civilizations, as the Celts were against Rome, the Mongols against Europe, the Vikings or Ottomans against Christendom.

Funny story about orcs. The accepted etymology of the word is derived from the latin deity Orcus, a god of the underworld, punisher of broken vows. The orcs as demon-type characters are prevalent in Italian folklore.

But orcs – not the Tolkien kind, but the actual kind – were, in fact, a people. A tribe. They were Celts living in what we know today as Orkney. They were, we think, Picts – a Brythonic people (until fairly recently in history, when their language and custom switched to Goidelic) who lived in the islands north of mainland Britain. The name is believed to derive from a Pictish tribal name related to pigs (young pig, to be more precise), literally ‘Orc.’ That’s it. That’s the word. Boars, for the record, were long celebrated symbols of warriors, as they are vicious, and difficult to kill. A whole herd of young boars would be a nightmare to face. The islands were annexed by Vikings, before being absorbed by Scotland in the 15th century.

There is an orcish woman quite popular in British folklore, by the by. Morgause, their queen, and an antagonist to King Arthur.

Skara Brae, in Orkney, another remarkable Neolithic achievement. What I wouldn’t give to walk around these stones.

The bias in fiction has now rightly fallen under a critical eye, just as many historians are pushing for a more whole view of history; that is, including the contributions and highlighting the lives and actions of women, demanding recognition and inclusion in history, just as their male peers were. Much discussion has been leant to the presence of people of colour in Medieval Europe. Yes, for the last time, there were, no matter how much we wish to white-wash the continent (Jesus was a brown man, and so was Saint Nicholas, even if we prefer to conflate him with images of a Christianized Odin) and its cultural life. Still more historians are bringing to light the existence and contributions of the LGBTQA+ community. All these things were previously missing in the academic spheres.

Their absence in our primary resources has undoubtedly directly resulted in their absence in our fiction; whom we consider heroes, whom we label as villains, and for what reason. The two absences are intricately linked, and it behooves any fiction writer doing research to bear these biases in mind.

Anyway, thanks for reading my rant.

I’m off to write about heroic orcs, now.

When S.M. Carrière isn’t brutally killing your favorite characters, she spends her time teaching martial arts, live streaming video games, and cuddling her cats. In other words, she spends her time teaching others to kill, streaming her digital kills, and cuddling furry murderers. Her most recent titles include ‘Daughters of Britain’ and ‘Skylark.’

https://www.smcarriere.com/

I believe the name of Tolkien’s Orcs is derived from a word in Beowulf referring to demons.

Do you read reviews in the Times Literary Supplement, the New York Review of Books, etc. and also notice the advertisements? There is an abundance of writing (and has been for decades) that would not fit into the Classical=good, barbarian=bad model, or the notion that women’s role in history is being suppressed.

When I taught college freshman composition and gave an assignment in which they were to choose some historical figure, I was struck by how little the students seemed to know about once-typical famous folk. But they did seem to know about Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Amelia Earhart. (I retired two years ago. I taught in rural North Dakota.)

Here’s something we can bewail together, the immense ignorance of American students about Jews. Almost all they seem to know about Jews is that 6 million of them were killed in the Holocaust.

Myself, I would say that’s even more to be deplored than ignorance about the ancient Celts.

While I wholeheartedly agree, that is well beyond the scope of this particular rant. Though, it might be something to think about this othering and how the biases in our study of ancient history contribute to that, no?

Again, though, not the topic at hand, and certainly not something that is within my academic purview, so I can’t speak more on the subject.

I do read, and so I’ve noted that there have been recent efforts to correct the horrifically colonialist bias in the study of history and it’s correlations, the aforementioned pro-Classical bias, as evidenced by the lecture I watched, remains dishearteningly persistent to this day.

And those biases, still in circulation, and certainly rife in primary sources, are what influences both how fiction is written, read and critiqued.

It is something worth commenting on.

Another good source for you to check would be the Chronicle of Higher Education, and perhaps in particular its Review (a magazine insert), where you will see plenty of evidence of the academic quest for the kind of diversity you call for. In the paper version, at least, you will find pages of announcements for new academic books — ! Take a look and I will need to say no more.

Just a quick comment that actually has little to do with the thrust of your rant, which is basically spot on, but a lot to do with the first image you chose to illustrate your column and drew me into it.

Back in the 1970s I spent a summer doing archaeology in the UK, and half the time I worked on various sites in the city of York. One weekend four of us rented a car and followed Hadrian’s Wall, camping out and sleeping on it at night. It was one of the best weekends I’d ever spent. If I’d stayed working within the UK I still might be an archaeologist, but my life eventually took another path. I do miss it, still, particularly the fieldwork.

That sounds heavenly to me, John!

It was great. York remains one of my all time favorite cities. Any place that has pubs with glass-topped tables that let you see down into Roman ruins is tops in my book.

Just to veer back into fiction — for what it’s worth, Robert Howard pretty much hated the Romans, fictionally speaking, at least. I don’t know if he took this stance to be a contrarian or just a plot hook to hang some of his stories on or it was an actual passion of his, but it’s clear in a number of stories and really stands out in “Worms of the Earth” (One of my favorites.)

Personally, I have mixed feelings about the Roman civilization, but I could say that about pretty much all of them. And, given our own current status (and, yeah, past)as Americans we should look to our own house.

Won’t a minor but significant factor in the initial bias towards Rome have been Latin? the ‘written word’, in an understood language, arriving with the blessing of the religious head of the dominant culture.

Though, obviously, other connections for Britain by the 18th century will have held even more sway; ‘Roman Empire = Christian Civilization = Our Civilization = Good’, however erroneous those connections were.

Talbot Mundy, at least in his Tros of Samothrace, was also no great fan of the Romans.

Although to an extent, I think both Howard and Mundy would’ve bought into the broad thrust of what you described above, with the “civilized” Romans vs. the “barbarian” natives — they just came down on the other side of the conflict.

Certainly, E. Lynden-Bell. And for Medieval chroniclers, it’s entirely understandable. For modern historians, the uncritical way in which that bias is transmitted gets on my nerves a great deal.

I’m honestly the same, Joe.

Academically, I do think Greece and Rome were remarkable. I do take umbrage, however, at the way they’re idolised in academic circles, to the point that other cultures are denigrated or have their achievements flat-out ignored. It is all, of course, in service to a hideous colonial history and outlook.

I do have to say that, on a personal level, my heart will always lie with the tribes of central and northern Europe, and the Atlantic Façade. I can, at least, recognise when they’re being horrific in the way many Classical admirers (particularly the more casual ‘academic’) seem unable with their chosen.

I guess the problem – which you touch on in your piece – is that the Roman Empire has been appropriated by some countries as an example of a ‘good’ empire (and therefore, as an oblique justification of imperialism) – e.g. Britian and more recently, the US.

Thanks for an enjoyable rant, which as you say at the end is more about heart than head. However, from a professional point of view I believe that the challenges are more practical than ideological. There are very few academic Classics departments in the UK, about twenty: the situation is much the same in archaeology. There are thus few academic posts. The holders of these posts must have very high linguistic and technical masteries: the disciplines are shaped by those masteries.

I remember reading what I think was a Choose Your Own Adventure style book as a teenager where the goal was to travel through time to discover the truth about King Arthur. In one choice, you end up watching Britons cheering for Boudicca’s rebellion. My knowledge of 5th century Britain at that point mainly came from Mary Stewart’s THE CRYSTAL CAVE, so I didn’t know who this woman warrior was, but I had the feeling I was too far back in time, since I thought I would know if there were any historical woman rulers in Britain around the time of King Arthur, I was also intrigued, because she seemed like a major historical figure I had never heard of, and why hadn’t I?