Cycles of History and the Eternal Church: Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr. First Edition: J.B. Lippincott, 1959.

Cover by Milton Glaser (click to enlarge)

A Canticle for Leibowtiz

by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

J.B. Lippincott (320 pages, $4.95 in hardcover, 1959)

This 1959 novel is one of the most popular and celebrated science fiction novels of all time. It won a Hugo Award and has a long list of critical citations. It’s set in the years following an atomic war, it portrays religion in a relatively favorable way (in contrast to the dismissive attitude of much other SF), and it dwells on the theme of man’s destiny, and its possibly inevitable fate in cycles of building and self-destruction. It’s sober and deadly-serious in parts, and it’s also quite funny in parts, which I hadn’t remembered since reading it decades ago. Something else I discovered when rereading recently: it doesn’t end the way I remembered that it did.

As this book is so well-known, I’ll summarize the plot only briefly. The book is in three parts.

Summary

The first part, Fiat Homo (Let there be man), is set some 600 years after a ‘Flame Deluge’ has destroyed civilization. (Some years pass in this section, at the end of which it’s the year 3174, so the book’s nuclear war apparently doesn’t take place until the year 2500 or so.) In the desert southwest Brother Francis Gerard at the Leibowitz Abbey stumbles upon (what we recognize as) an ancient fallout shelter, and discovers artifacts which may have belonged to Leibowitz himself – including a shopping list (“Pound pastrami, can kraut, six bagels—bring home for Emma”) and what we realize are radio parts and a blueprint, but which no one at the abbey understands in the slightest. Messengers arrive from New Rome, somewhere in the East, because Leibowitz is under consideration for canonization, and there’s some concern that if the artifacts are fake they would jeopardize that process. Eventually New Rome approves, and Brother Gerard is allowed to attend the ceremony, though on his return journey (– spoiler –) he is killed by mutant ‘sport’.

The second part, Fiat Lux (Let there be light) is set 600 years later. Society is recovering, as a political leader in Texarkana is anxious to unite the continent, dealing with various local tribes to do so – planning to wipe them out with cattle plagues if necessary. A secular scholar, Thon Taddeo, still curious about the authenticity of the Leibowitz documents, travels to the abbey, where the brothers have managed to re-invent a dynamo and an arc lamp. Taddeo studies the documents and reports his findings, careful not to offend the brothers’ religious sensibilities. News come of another war, and a message that the surviving mayor of Texarkana has broken with the church.

The third part, Fiat Voluntas Tua (Thy will be done) is set another 600 years later. Technological society has recovered, and there are spaceships again, and even colonies on worlds of several stars. This section reads like a contemporary political thriller, with rumors about use of atomic weapons. A secret plan of the church goes into effect – to launch its own starship to Alpha Centauri, with a sufficient number and kind of volunteers to establish a new church hierarchy. As the bombs fall and the abbey is destroyed, priests at the launch site in New Rome lift children into the rocket ship, and the ship takes off, escaping the earth.

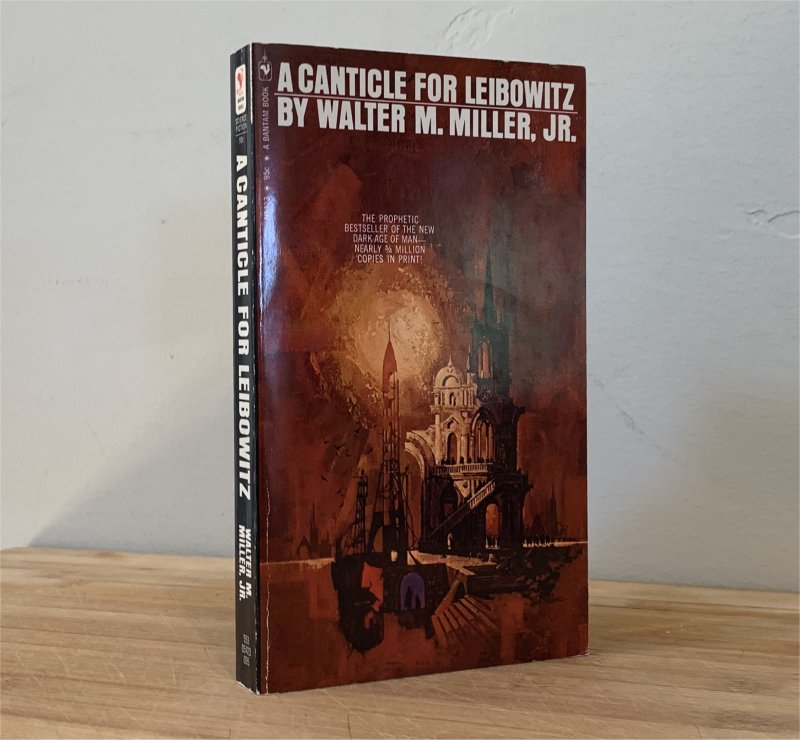

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr. Bantam, 16 printing July, 1972.

Cover art by Lou Feck (click to enlarge)

Bantam used this cover art on 29 printings from 1961 to 1982.

Major points

- What I had misremembered from reading this novel decades ago was the nature of the escape at the end. The novel’s arc goes from destruction to civilization to destruction again – with the rocket launched by the Church implicitly saving the last gasp of humanity to survive on another world. But – humanity has already settled other planets! (We’re told this at the beginning of Part Three.) The only thing being saved at the end here is the church itself. That’s why there’s such concern in the final weeks about the proper composition of the crew on the rocket—they need the correct church officials on the new planet so they can perpetuate church hierarchy. The book leaves you with the flavor that the church has saved humanity. But it hasn’t.

- Given that understanding, the novel still gives great credit to the church for preserving knowledge over hundreds of years that otherwise would be lost. But—it’s always “the” church, the Catholic Church of course, and there’s never the slightest acknowledgement that there might be other religions in the world, or even protestant churches. (Ironically, it was Islam in Europe’s Dark Ages that preserved knowledge of the Greeks that the Christian church condemned.)

- At the same time, while the author takes this church business very seriously – for example, the passionate debate about euthanasia for those poisoned by radiation (Chapter 27) — he surely is wise to the ways of human culture and how stories grow in the telling, how other species might think the world was created for themselves, and so on.

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr. HarperCollins Eos, 2006.

Cover illustration by John Picacio (click to enlarge)

Other interesting notes and quotes

- (Page references are to the HarperCollins Eos edition shown in the photo above.)

- P62, how after the first atomic war, the populists strike out at the elites [to use modern terms] to destroy what’s left:

So it was that, after the Deluge, the Fallout, and plagues, the madness, the confusion of tongues, the rate, there began the bloodletting of the Simplification, when remnants of mankind had torn other remnants limb from limb, killing rulers, scientists, leaders, technicians, teachers, and whatever person the leaders of the maddened mobs said deserved death for having helped to make the Earth what it had become. Nothing had been so hateful in the sight of these mobs as the man of learning, at first because they had served the princes, but then later because they refused to join in the bloodletting and tries to oppose the mobs, calling the crowds ‘bloodthirsty simpletons.’

- Is it odd that Brother Francis takes it upon himself to create an illuminated copy of the ancient blueprint he’s found? Perhaps, like the medieval monks, these later brothers have little else better to do.

- There’s a fantasy element in the novel in the implication that the pilgrim at the beginning is the actual Leibowitz – or is he the famed Wandering Jew? Note, p168b, how the hermit seems to remember thirty-two centuries.

- There is occasional broad humor. How Brother Francis is dimwitted; the battle with the Autoscribe machine in Chapter 24; the story of the brother’s discovery grows in the telling, p88:

Brother Francis closed his eyes and rubbed his forehead. He had told the simple truth to fellow novices. Fellow novices had whispered among themselves. Novices had told the story to travelers. Travelers had repeated it to travelers. Until finally—this!

“No halo?” “No heavenly choir?” “What about the carpet of roses that grew up where he walked?”

- On the responsibility of academicians to control the power they give rulers: p220.8

But you promise to begin restoring Man’s control over Nature. But who will govern he use of the power to control natural forces? Who will use it? To what end? How will you hold him in check?

- In Chapter 22 (p228) the scholar discovers a book that suggests the man is not descended from Adam, but is a servant species created by the original humanity. Others reply that what he is reading is just a play, and speculate on his motives. (After enough time has passed, how can you tell between history, myth, and fiction?)

“I only offer the conjecture that the pre-Deluge race, which called itself Man, succeeded in creating life. Shortly before the fall of their civilization, they successfully created the ancestors of present humanity—‘after their own image’—as a servant species.”

“But even if you totally reject Revelation, that’s a completely unnecessary complication under plain common sense,” Gault complained.

- Ch 12, a scholar and a politician debate why civilizations fall.

“How can a great and wise civilization have destroyed itself so completely?”

“Perhaps by being materially great and materially wise, and nothing else.”

“…during the time of the anti-popes, how many schismatic Orders were fabricating their own versions of things, and passing off their versions as the work of earlier men. You can’t know, you can’t really know. … But where is the evidence of the kind of machines your historians tell us they had in those days? Where are the remains of self-moving carts, of flying machines?”

“Beaten into plowshares and hoes.”

- Each section ends with an appearance by buzzards. Section 2, p239:

As always the wild black scavengers of the skies laid their eggs in season and lovingly bed their young. They soared high over prairies and mountains and plains, searching for the fulfillment of that share of life’s destiny which was theirs according to the plan of Nature. Their philosophers demonstrated by unaided reason alone that the Supreme Cathartes aura regnans had created the world especially for buzzards. They worshiped him with hearty appetites for many centuries.

- And the book ends with haunting lines that might just as well suit Earth Abides.

A wind came across the ocean, sweeping with it a pall of fine white ash. The ash fell into the sea and into the breakers. The breakers washed dead shrimp ashore with the driftwood. Then they washed up the whiting. The shark swam out to his deepest waters and brooded in the cold clean currents. He was very hungry that season.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared at Views from Crestmont Drive.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was Collision Course by Robert Silverberg. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive.

I read it in 1960, when I was in high school, and thought it was just so-so. Obviously, I didn’t have your insight.

My memories of this book are pretty dim. All I took away from it was the cyclical nature of history – ie, post apocalypse, recovery, apocalypse – with the church surviving throughout. Plus a certain black humour. I only discovered afterwards that it was an amalgam of three discrete stories, which makes sense, as the narrative thread connecting the three sections is tenuous at best.

I reckon the Catholicism is modified to some extent by how Leibowitz is a Jewish convert motivated by a desire to preserve knowledge rather than by a religious epiphany – ie, that his subsequent canonisation is a sort of black joke, as he is hardly representative of the church which venerates him. Maybe the corollaries with Christ only emphasise this irony?

A great book! True story, I was attending WisCon in 2008 and staying at a youth hostel. The hostel’s library had a beat up copy of “Canticle” and I swapped it out with my crisp new “Red Mars” book that I had bought at the con.

I have always liked the line about the buzzard philosophers.

> True story, I was attending WisCon in 2008 and staying at a youth hostel. The hostel’s

> library had a beat up copy of “Canticle” and I swapped it out with my crisp new “Red Mars”

Adrian,

Great story! Was that the same Wison we attended a midnight group reading with C.S.E. Cooney, Jason M. Waltz, Amal El-Mohtar, and Shveta Thakrar?

I still remember your reading! There were half a dozen young women offering constructive criticism on your sex scene. Good times, good tines.

“(Some years pass in this section, at the end of which it’s the year 3174, so the book’s nuclear war apparently doesn’t take place until the year 2500 or so.)”

I think you’re misreading the end of the chapter. I took “Eventually it was the Year of Our Lord 3174” as indicating when Fiat Lux is set. The shelter documents, contemporary with Leibowitz, date from the 1950s and 1960s:

“The dates ranged through the latter part of the fifth decade, and earlier part of the sixth decade, twentieth century. Again it was affirmed! — the contents of the shelter came from the twilight period of the Age of Enlightenment. An important discovery indeed.”

A quibble:

“preserved knowledge of the Greeks that the Christian church condemned”

Not exactly. Medieval Islam did do a lot with classical philosophy and astronomy, but the Western Church didn’t condemn that stuff; they used it, needed it. But unless it was written in Latin, few if any people in the West could read it. The more that changes, the nearer the west is to the Renaissance. (And, in the Eastern Church, that Greek stuff had never been lost.)

Less quibbly:

Thanks for this thoughtful and detailed review. I haven’t read this book in a long time, and I think I’ve been misremembering the ending the same way you mention.

I first read the book in the mass-market Bantam edition with the gorgeous bronze-gold-black cover by Lou Feck (says ISFDb). My current edition is a trade paperback with the original cover by Milton Glaser. For sentimental reasons, I’d like to lay hands on that old Bantam, but I see that it’s running for $1,150.33 on ABE Books, so that seems a little unlikely.

I have the April 1955 Fantasy and Science Fiction issue that contains Mr. Miller’s original story, “A Canticle for Leibowitz”, and it is essentially the opening section of the novel, “Fiat Homo”, the story of Brother Francis Gerard discovering the Leibowitz cache and devoting his life to making an illuminated circuit diagram. In the story, the Blessed Leibowitz lives through the Deluge of Flame, which is the reason he becomes a monastic founder. And the story is set 6 centuries later than Leibowitz’s time, which dates to 1956 (the date on his circuit blueprint). Of course, the dating could be changed from story to novel version.

And the mysterious pilgrim is given a connection to Leibowitz, as he is described wearing a burlap loincloth, a detail that troubles the abbot, who recalls a legend that Leibowitz had been hooded with a burlap bag when he was lynched for being a scientist.

Thanks for the comments. I’m glad this is a book still alive for many readers. James Davis Nicoll, I’ll re-examine the end of that chapter. James Enge, point taken; I’m over-accounting for my early amateur astronomy phase, when I learned why so many star names are of Arabic derivation…