The Ground Rules Have Been Put in Place: Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery, by Brian Murphy

|

|

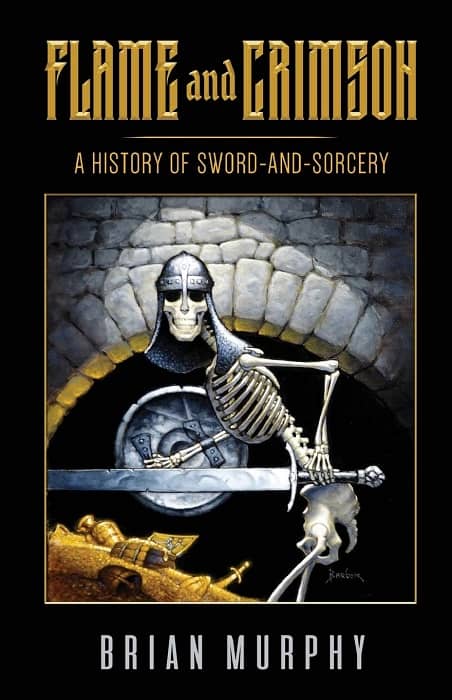

Cover by Tom Barber

Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword-and-Sorcery

By Brian Murphy

Pulp Hero Press (282 pages, $19.95 in trade paperback/$7.99 digital, January 16, 2020)

At long last, we have a history of the sword-and-sorcery genre, and a very welcome and erudite study it is. Brian Murphy is to be commended for his honest appreciation of our frequently dismissed and often mocked genre. He intelligently surveys the expanse of the sword-and-sorcery field warts and all, low points and high, putting the genre into its proper literary perspective.

To present a linear history of the sword-and-sorcery genre is in fact to dissect an Yggdrasil of many branches, which is precisely what Murphy has done here. His challenge in undertaking Flame and Crimson was great—confronting a century of work and reducing discussion of it to the reasonable length of about 250 pages. He has risen to the challenge.

(Full disclosure: I am mentioned a few times in Flame and Crimson and am cited in a pull-quote in the header to chapter 1. I am also published by Pulp Hero Press, the imprint that has brought out Flame and Crimson.)

[Click the images for Conan-sized versions.]

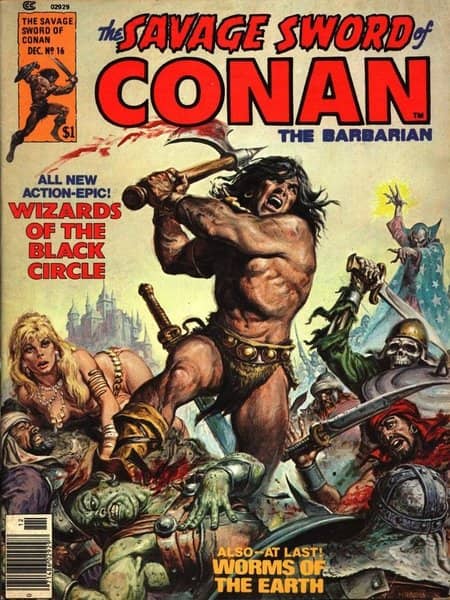

Savage Sword of Conan 16

In a brief introduction, Murphy tells us that he came to appreciate the genre by way of first reading high fantasy, getting to the red meat later when he found a copy of Marvel’s Savage Sword of Conan, a magazine “both dangerous and adult,” and so moved on from The Sword of Shannara to the harder stuff, dark and violent fiction in which “the blue blades flame and crimson.” (I like his using those words as verbs. They beckon the primitive.)

He bookends his study with two important chapters, with his initial question “What is Sword-and-Sorcery?” ultimately addressed in the final chapter, “Why Sword-and-Sorcery?” In between, he takes us on a journey beginning with the roots of what is to come, discussing Edgar Rice Burroughs and early fantasy — proto-sword-and-sorcery — as that written by Lord Dunsany and A. Merritt.

Then we are on to Weird Tales and Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith and such successors as Henry Kuttner, thence into the postwar trough in which the fires were kept burning, despite commercial malaise, by Fritz Leiber and Michael Moorcock, just this side of the Lancer series of Conan volumes and the landslide that would follow, which Murphy labels a renaissance. Here we had such artists as Jack Vance, Poul Anderson, and Karl Edward Wagner in the heady days of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as younger writers just breaking in, succeeded by a decline and fall — the “Clonans” and paperback hackwork and Lin Carter’s endless parade of derivative fiction, so many titles that filled the wire book racks in a glut of stupidity. Add to that the many movies, most of them even more superficial than the worst of the word works.

By the time it was all done with, anything worthy or serious, such as Charles Saunders’ Imaro titles, was nearly lost under the landslide. Replacing these muscular volumes on the shelves was a surge of Tolkeinesque fantasies, a parade of world-building tomes the thickness of medieval Bibles — epics and soap operas nearly as indistinguishable en masse, with their high fantasy covers of dragons and deep forests and ladies in white robes, as had been the plethora of naked barbarians and wenches and tentacled things that preceded them.

Return to the “days of high adventure” came, not in a return of mass corporate commercialism, but in a variety of ways, which Murphy details with care. Gaming was, and is, paramount to the new generation of writers and readers, as was, and is, heavy metal music — a refuge for what is soul-deep in the sword-and-sorcery sensibility. David Gemmell largely managed to keep to his sword-and-sorcery roots, making it through the tide of soap operas, and then came Joe Abercrombie, Richard Morgan, Mark Lawrence, and Glen Cook, as well as novels based on war gaming and tabletop games.

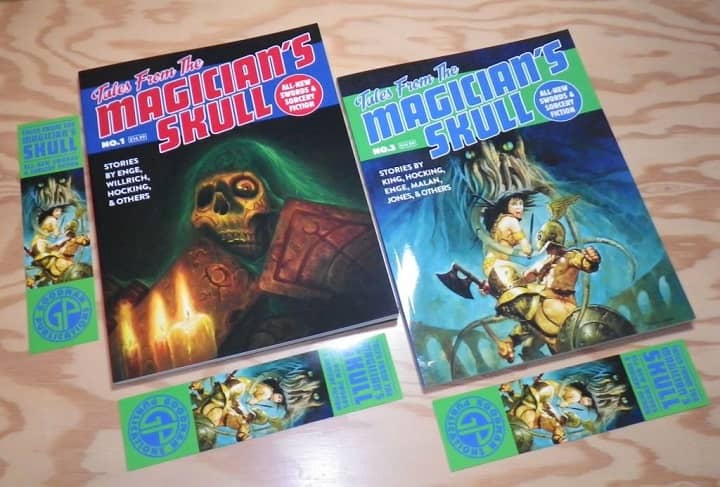

Tales From the Magician’s Skull, issues 1 & 3 (Goodman Games)

Thus the branches of the tree grew and spread and continue to do so, specifically through many online publications as well as continuing efforts to keep such fiction in print in magazines, as with Tales From the Magician’s Skull. Robert E. Howard tapped into something deep in us when he crafted the first of these stories, and what is elemental and ever ripe in the genre has continued, with the best authors striving to create good work despite the many dead ends and debacles we have endured.

Of value to me is that Murphy is a generation younger than I, meaning that he brings a perspective to this field different from that of the writers of my generation, those of us who started out in the fanzines of the 1970s and contributed to the paperback racks during the decline and fall, the late period of sword-and-sorcery’s long run that had begun in the 1960s. Murphy came of age surrounded by fantasy and sword-and-sorcery; it was in the air, and on the gaming tables, in the paperbacks, in the movies, in the music.

The writers of my generation had books and the occasional Ray Harryhausen movie. It strikes me that writers of my generation may have therefore grown up feeling somewhat protective of our genre; it was uncommon, and those of us who read what we could of it and who wrote it were eccentric, speaking a language few others understood. The idea that fantasy, that science fiction, that comic magazines and movies would, within twenty years, dominate popular culture and lead, for example, to traffic-stopping national conventions filled to overflowing with eccentrics like us was unimaginable.

But Murphy’s having grown up in a time when eccentricities and artistry are the norm and are, in many ways, encouraged allows him valuable insight into both the history of the sword-and-sorcery genre and its possibilities. I find his long view educational. He is at home with the fact that, for instance, there are many more women writing fantasy today, some of them hard fantasy, than there ever were in the days of the fanzines. And he is comfortable with fiction written by writers who have come to the field by way of comic books and Dungeons and Dragons. The fact that dark fantasy is now mainstream and that eccentricities are now regarded simply as matters of choice or personal attitude are things that only those who grew up recently could have experienced. And to have imaginative fiction be taken seriously by students and academics and scholars? Remarkable.

It is the scholarly attention that Murphy brings to Flame and Crimson that will prove to be most worthwhile in the long run, for it gives us a foundation for further discussion. The ground rules, as it were, have now been put in place — an important milestone for continuing engagement with sword-and-sorcery by critics, thinkers, and writers from now on.

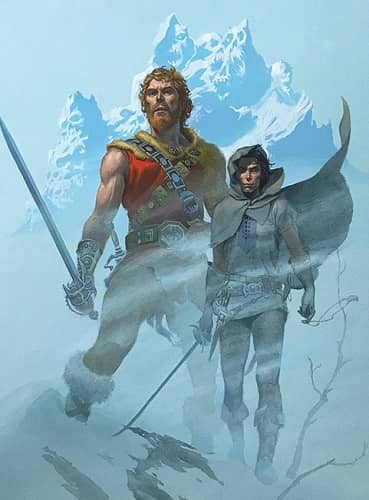

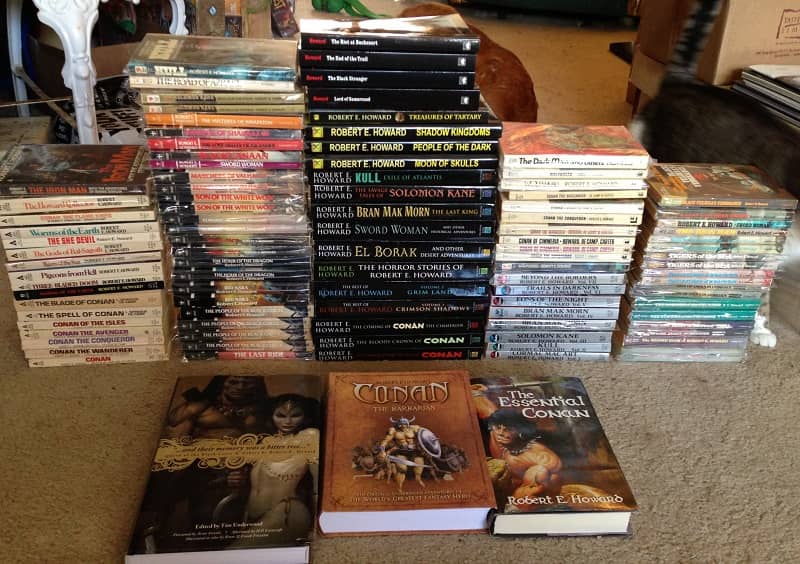

Some of the collected fiction of Robert E. Howard

For example, Murphy’s appreciation of what Robert E. Howard was up to as a writer is precise and accurate:

Howard relished literary experimentation and genre-mixing…. He was also a first-rate talent, a natural storyteller who worked with an effortless, muscular prose style that propelled the reader along.

Regarding the creation of the Hyborian Age, essential to Howard’s development of sword and sorcery, Murphy quotes Jeffrey Shanks: “[H]e created a fictional setting that was steeped in realism unprecedented within the genre of speculative fiction up to that point.”

It is this sense of realism, of verisimilitude, that sets sword-and-sorcery apart from its cousin high fantasy — that, and the sense of personal integrity and the need for freedom in its protagonists, qualities evident in Howard himself. And these are the qualities that define the sword-and-sorcery template, as Murphy defines it, so familiar to readers of the genre. The template gives us, in the best stories, romantic echoes of the frontier in deeply experienced, melancholy, morally ambivalent men and women making their way as best they can in their violent, dangerous worlds, but also gives us, in the worst stories, ogres content to smash, grab, kill, and wench in predictable storylines on the level of old Saturday morning cartoons.

There is the template. More deeply, What is sword-and-sorcery? In his first chapter, Murphy discusses the basic elements in detail. They are the ingredients known to all of us: men and women of action, typically with personal or mercenary motives; dark and dangerous magic and, most importantly, the breath of horror; and the inspiration of history or historical fiction. Murphy emphasizes that sword-and-sorcery fiction is often presented in short, episodic stories — and the argument can be made, in fact, the genre is best served by work done in short form. Critically, Murphy also points out two truisms: “The subgenre is rooted in realism” and the plain fact that most sword-and-sorcery protagonists are outsiders. “Many of sword-and-sorcery’s iconic authors were themselves outsiders,” he points out, something frequently overlooked but no doubt reflecting the eccentricity of true artists as opposed to the mundane personas of more commercially astute writers.

These are the basic elements of sword-and-sorcery fiction’s What is it? Yet, as is true of the best art anywhere, the best sword-and-sorcery fiction is more than the sum of its parts, as Murphy makes clear in his last chapter, “Why Sword-and-Sorcery?”

|

|

|

Max Weber, H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard

Murphy begins his answer by quoting Max Weber’s famous observation regarding the disenchantment of the world: “The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world.” Howard and Lovecraft both railed against the “Machine Age” into which they had been born and envisioned other times likely better suited to their temperaments. We now know that the disenchantment of the world that Weber identified was the reality for the Twentieth Century and beyond; we live with this sensibility still. So one important function of sword-and-sorcery is an intellectual exercise that it offers the reader:

Few fates are more enervating than an inability to change one’s circumstances, and being a cog in an uncaring mechanical universe. Sword-and-sorcery rages against this machine. It offers the modern reader an alternative, posing the question: Which is the superior? The old barbaric ways, in which life was nasty, brutish, and short, but men and women were at least masters of their own fate, operating with a heightened awareness borne of daily struggles for survival? Or the modern industrialized state, in which we accept security and civility and predictability in exchange for hyper-specialized, disconnected jobs, purposelessness, and widespread anxiety and depression?

These are not irrelevant questions; they go back as far as we do, to the choice our ancestors had to make between remaining hunter-gatherers or compromising their autonomy to live within walls. Even today, many of us choose to live off the grid, just as some of our forebears went up into the mountains or out into the hinterlands to live life on their own terms. If it is the call of the wild that these people were answering, it is not a foolish one but one rooted in our history, and it echoes still in passages in sword-and-sorcery stories.

|

|

|

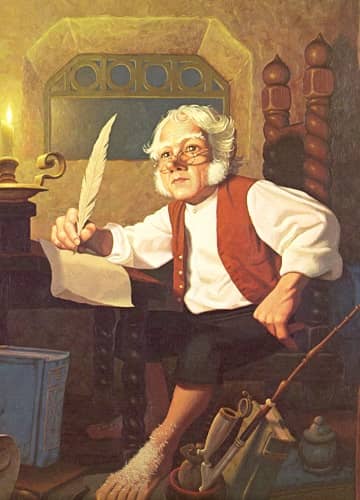

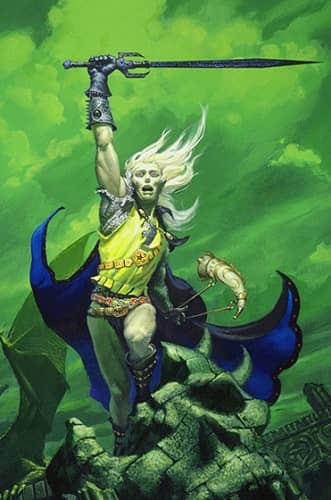

Bilbo Baggins, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, and Elric of Melniboné. Art by Greg and Tim Hildebrandt, and Michael Whelan

Artistically, even as Murphy concedes that much sword-and-sorcery fiction is written for and read as entertainment, he notes that it

fills an aesthetic void left by high fantasy. It brings to center stage the outsider, the hero on the periphery. Instead of the king-in-waiting Aragorn, or the conservative, lover of hearth-and-home Bilbo, sword-and-sorcery offers the likes of Gray Mouser and Elric of Melniboné — lusty nonconformists, disaffected political anarchists, wanderers, and wayfarers. Its heroes offer a voice for the disaffected.

The genre also acknowledges “our species’ fascination with and predilection for violence”— no small thing.

Most importantly,

[t]he barbaric template offered by sword-and-sorcery fiction is a myth. In almost all instances it ignores historical barbarism’s gross inequalities and abhorrent traditions. But historical fidelity is not its intent. Its heroes are a facet of our humanity, a reminder of the potency of individual sovereignty and human agency.

The best sword-and-sorcery fiction gives us the sensation of our having experienced something we have lived through. It removes the space or distancing of high fantasy, the pretense, the performance. Good sword-and-sorcery fiction can shock us awake; it gets into the trenches, traverses the swampland, climbs the mountainsides, enters the cold tombs, explores the ruins, and enjoys lusty free-for-alls, the combat and the soft flesh and the stinging wine, with senses keen at every step, with the immediacy of life lived. And frequently the sword-and-sorcery protagonist is confronted with a problem many of us might find at least as troubling as confronting a monster with tentacles: What do we do when we are out there on our own? How do we manage when we are utterly alone?

We know that genre fiction can provide us environments and milieus as exact as life, can give us characters that become as true to reality as anyone we know, and can wrestle meaningfully with ideas and concepts and values. Westerns have done this; detective stories and science fiction have, too. So has sword-and-sorcery. It’s the verisimilitude that does it, the author giving us something that we felt was there all along and needed only the words to bring out. Paint-by-number fiction cannot rise to this level; well-done fiction can, and sword-and-sorcery fiction, the best of it, has done it.

Flame and Crimson not only provides a history of the genre but also establishes its credentials as worthy of further study. For myself, I wish that an index had been provided; it would have been invaluable, given the plethora of information Murphy provides. But as further branches on the tree, many chapters feature sidebars at the end, thereby making room for discussion of such topics as Jack London’s influence on Robert E. Howard, heroic versus anti-heroic sword-and-sorcery, and paperback cover art, the forward face of the genre. Additionally, the author gives us “A Probable Timeline of Sword-and-Sorcery” in an appendix. And the presentation is excellent; it’s a good-looking, sturdy Pulp Hero Press volume with an unsettling Tom Barber cover, to boot.

Brian Murphy has given us a job well done; to quibble with some of his assertions would be beside the point: come up with your own, and let’s keep the conversation going.

Flame and Crimson belongs on your shelf right now.

Buy this book.

David C. Smith (born August 10, 1952, in Youngstown, Ohio) is an editor, writer, and author, recently retired after working nearly thirty years as a medical editor and managing editor of a peer-reviewed orthopaedic journal. He is the author of twenty-six novels and collections and of many short stories and articles, as well as of a post-secondary English grammar textbook.

David C. Smith (born August 10, 1952, in Youngstown, Ohio) is an editor, writer, and author, recently retired after working nearly thirty years as a medical editor and managing editor of a peer-reviewed orthopaedic journal. He is the author of twenty-six novels and collections and of many short stories and articles, as well as of a post-secondary English grammar textbook.

He loves writing and editing and the English language and is available as a freelance editor. Smith lives in Palatine, Illinois, with his wife, Janine, and their daughter, Lily, and their cats, Rosebud and Corabelle. He is on the web at blog.davidcsmith.net and on Wikipedia at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ David_C._Smith_(author).

His last article for Black Gate was The Genesis of The Fall of the First World.

Its on the wishlist. Does the book go into more unknown S&S authors?

I loved FLAME & CRIMSON! You can read my review here: http://georgekelley.org/fridays-forgotten-books-585/

Thanks for the outstanding review David! This means a lot coming from the author of Oron and the Red Sonja series. I’m glad in particular you enjoyed the “Why sword-and-sorcery” chapter. I put a lot of my heart into that one. Thank you for your contributions to the genre.

Glenn: I’m not sure what you would consider obscure. I spent most of the book covering the foundational authors—Howard, Leiber, Moorcock, Smith, Moore, Kuttner, then Vance, Anderson, Wagner. Elsewhere folks have said that Chapter 8 covered some of the 80s authors (Gemmell, Cook, etc.) that typically don’t get as much ink. I do als spend some time on Saunders, Campbell, and of course De Camp and Carter.

Last commenter: Thanks for the review and I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Thanks for the review David. As usual, your thoughts are incisive and interesting to read. I’d love to see you post more here at BG.

By the way, we met last summer at Howard Days. I have the privilege of hearing your guest of honor talk live. Too bad we can’t have Howard Days this year. Hopefully in 2021 we can all return to Cross Plains.

This is a most excellent review, Dave! My copy of the book is coming to me. Looking forward to reading it.

[…] everything clicked for me. Of course, a story that holds all of Jones’ 4 ingredients and Murphy’s 7 parameters should be a S&S tale — but it is not a guarantee, for there are many that are not. And […]