“Authenticity” in Sword & Sorcery Fiction

Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?

These days, in intersection with my Conan gaming (I enjoy both Monolith’s board game and Modiphius’s roleplaying game), I have been reading a lot of two things: weird fiction from the turn of last century into, maybe, the 1940s; and sword & sorcery — anything that, on its cover, features a muscled male wielding medieval weaponry — predominantly from the ‘70s or ‘80s. (This latter does the double duty of encouraging me to work out.)

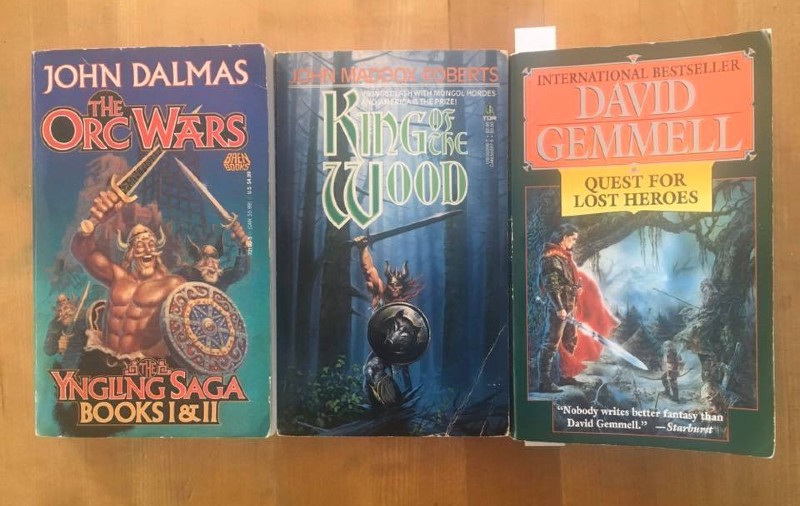

As is to be expected, these works offer various levels of quality. Early-last-century weird fiction is in a class of its own, and, though writers of that era freely borrowed tropes, themes and elements from each other (they very much appear to have been in conversation, literally or otherwise), the form of the weird tale is not as calcified as that of sword & sorcery appears to be by the ‘80s. Even within this latter’s straitjacket, however, I have encountered some standouts, including John Dalmas’s The Orc Wars (beginning with The Yngling, 1971), Gordon Dickson’s and Roland Green’s Jamie the Red (an unofficial Thieves’ World novel, 1984), and John Maddox Robert’s The King of the Wood (1983). Why I like these is for the reasons that one would like any work of fiction, of course, but with one addition: they present a sense of verisimilitude. I should add here, for anyone who might not be privy to how sword & sorcery is supposed to be subdivided from its parent genre of fantasy, that sword & sorcery is supposed to be more “realistic.” The world presented in such tales is premodern. Life is hard. The cultures do not have our present technology (nor magic — magic, in this subgenre, if not “low,” is rare and mysterious and terrifying and usually very, very “wrong”) with which to ease the drudgery of existence. In other words, the characters in such stories live in the way that folks in the Middle Ages lived, possibly in the way that many of our grandparents or great-grandparents lived, if they were homesteading somewhere.

This is why I no longer write sword & sorcery. I am a city boy. I am modern. I have no idea what “real life” is like. And yet I somehow have enough of one to know — intuitively or otherwise — when a writer knows even less than I do. To catalog the many errors of some of our most famous current fantasy writers is outside of the scope of these observations, but I’ll point to the occasion that spurred me finally to write on this topic here.

I recently picked up one of David Gemmell’s highly regarded installments in his Drenai Saga, specifically Quest for Lost Heroes (1990). First, I must insist that the book is good. I particularly like the characters and the drama and tensions that are developing around them. Most of this is “believable.” What is taxing, however, are some of Gemmell’s representations of a premodern world. Most of these are present in throwaway lines, which usually amount to an eyebrow raise or a cringe, but nothing profoundly deal-breaking. His representation of a certain smithy was a little tougher. First, there was more than one smith in the town, and by that I mean more than one smith that, specifically, made weapons. Second, this guy had whole selections of armaments just hanging on his walls, in more than one room. This is a little more than cringe-worthy, but I let it go with a shrug. Oh, well. This is a fantasy world, I thought. Maybe they have a whole lot of ore around here, and maybe this smith is independently wealthy enough to just have a whole department store of weapons for customers to browse.

I don’t know if I can forgive what comes next, though. In chapter three, two bowmen drop a deer and no sooner set about “butchering” it when (in what seems within a pretty fleet passage of time) some ruffians arrive. They also want the deer. After a bow fight, the original deer hunters make off with their prize, fleeing bandits who have survived the battle:

Hastily the two men dragged the butchered deer back out of range, stacked the choicest cuts of meat inside the skin, and faded into the woods.

To independently account for this, to forgive this, I must add to this world’s immense amount of iron ore a species of deer that all but butchers itself and packs itself in its own skin within minutes of being pierced by an arrow. Though I’m a city boy, I come from a family of dairy farmers, and, while I was growing up, every year, every available man (and some women) gathered themselves into parties for deer hunting. So I know that what Gemmell describes here just isn’t possible. First, one is not likely to “butcher” a deer where it falls. It’s dirty there. What are you going to do with the meat? More likely, you’d hoist the carcass up somehow on a rope — perhaps up on a tree limb. In this way you could work more easily, and maybe spread something out underneath to catch the cuts of meat.

But even this proposed method is unlikely. It’s not so simple to skin a deer. When “fresh,” that skin holds tightly to the muscles. It’s almost glued on. This is why hunters typically “hang” their deer in a cool place for usually a week or more. Natural decomposition produces enzymes under the skin that help separate the hide from the meat. Even after this process, though, it takes a lot of strength — a lot of braced, two-fisted strength — to seize that hard, rubbery stuff and yank to tear it down off the muscles.

Okay, so I’ve revealed myself as a “nerd” about deer hunting. So what. It’s fair to ask about my “point.” My point might be that our collective experience within the natural world has drifted so far that we no longer understand it. As a result, our fantasies are even more fantastical than many of us might even realize. The presence of “magic,” in such works, might be the least of it. It reminds me of an anecdote about the animator and film maker Hayao Miyazaki. When confronted with artists who were unable to produce believable flames, Miyazaki raged, “Go outside and build a fire, for once!”

My grandfather, Trygve Orlando Dybing (1915-1996), was a great reader of Westerns, particularly of those penned by the ubiquitous Louis L’amour. I picked one up, once, and was very impressed. It read like a visceral pulp. I wonder what those stories were like in the mind of my grandfather; he certainly lived a life that could determine the veracity of L’amour’s fancies. I likewise wonder how much direct experience L’amour had with his subject matter. I know that many writers do have this expertise: Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, Herman Melville. Is it perhaps too much to ask that our writers of adventure fiction be adventurers themselves? Maybe so. But can’t they, at the very least, take a blacksmithing class, plant a garden, participate in a harvest, weave some fabric, preserve some food, and — if they don’t want to hunt and kill an animal for themselves — at least talk to someone who has?

Kind of a likeminded follow up to “Neverwhens.”

Great to see Sword & Sorcery return to Black Gate. Seems like it has been a really long time.

Though I am wondering if this maybe just was an elaborate way to say “Do your research!”, which obviously applies to all fiction writing.

A great sister-article!

About Gemmel and smiths…depends on time and place. In the late Middle Ages, cities like Milan and Nuremberg had multiple armour shops, multiple cutlers (armourers don’t make weapons, and blade-smiths don’t make swords — they sell them to cutlers who hilt and balance the weapon) and multiple blade smiths. Water-wheel tech meant that blades were mass-produced. There were villages in which the principle craft was mail-making as early as the 1200s…Then there were totally separate guilds making padded armour.

OTOH, plate armour, beyond helmets, gauntlets and breastplates, is largely one size fits a few — and the idea of open show-rooms is pretty off.

There was also a HUGE market of used clothes, weapons and armour, especially after campaigns, when mercenaries would divest themselves of gear.

The Merchant of Prato, written by a real, 14th c Tuscan merchant, really provides fascinating insight into this.

And of course, this assumes 1400s level technology. An early medieval setting is quite different, as is a high medieval one.

So nice to see someone mention King of the Wood. I just read it this past year — what a little forgotten gem, as was the quirky Orc Wars.

Greg, you are an info god! Thanks so much for reading!

Greg, it suddenly occurred to me to check with you about the veracity of these gorgeous passages in _King of the Wood_. They strike me as very cool and evocative. I shared them at the Conan 2d20 forum in interest of “gamifying” them.

“A few of the men were donning jackets covered with scales of horn, but Hring had little faith in such protection. His mail shirt would drag him to the bottom if he should fall in. Except for his helm he wore only his sailor’s loincloth. He knew that, unless armored, it was unwise to wear a shirt or trousers into a fight. A cut from a sharp blade was likely to be clean, but if bits of cloth or leather were carried into the wound, it would fester.”

And…

“The spears had stone heads, and along the sides were rows of shark’s teeth, set in pitch-filled grooves and laced with rawhide thongs, pointing backward. Those teeth could drag a man’s guts out when the spear was withdrawn.”

https://forums.modiphius.com/t/armor-and-infection-and-shark-tooth-spears/9806

So, the Carib spears are quite accurate, and shark-tooth lined weapons are also found throughout Polynesia.

Roberts (quite the history nerd himself) is also accurate that one of the problems with medieval wound infection was fabric, broken mail links, etc., being driven into the wound.

The horn scale armour…well, such things did/do exist in various cultures, but the Norse were using little scale armour by the time the “Vikings” in this setting move to North America, and the lamellar armour they used seems to have been mostly ferrous or leather. Having said that, a number of native peoples were using bone armours going back to the Neolithic, so I was able to just see that as a “Skraeling” influence.

Greg Mele, you are awesome. Thanks for the answers! I think I definitely have a sense for who are the “history nerds” writing S&S. That’s the stuff I like best!

[…] (Black Gate): These days, in intersection with my Conan gaming (I enjoy both Monolith’s board game and […]

[…] (Black Gate): These days, in intersection with my Conan gaming (I enjoy both Monolith’s board game and […]