Neverwhens, Where History & Fantasy Collide: Witcherian Swordplay and…. er… 14th century Mullets?

OK, this is just STUPID, assuming one likes their fingers. (If, you are also angry that a guy in vaguely

Renaissance clothing is swinging a Roman gladius at a man with a medieval longsword,

I salute your attention to detail, but you’re probably watching the wrong show.)

There’s an interesting side-effect to being a researcher and author on historical, European martial arts (HEMA), especially when you also own a large, full-time school for the same in a major city. I wish I could say that side-effect is vast wealth and fame (someone pass a Kleenex to my wife, she always tears up when she laughs), but instead it is that, every time there is a major media event involving something sword-like, a well-meaning reporter wants your take on its authenticity. This happened almost every season during Game of Thrones, until I quipped “the show is so much more exciting when everyone keeps their swords sheathed,” and perhaps the funniest one was when The Force Awakens came out and the interviewer wanted my take on Kylo Ren’s new lightsaber style with its cross-guard/vent thing. I tried to give an honest answer:

Well, that seems a great way to cut your own arms off, but it sure looks neat. As to how they fight with the saber… I have to be honest, I have no idea how a psychic, telekinetic space-wizard uses a very light, edgeless plasma-beam trapped inside a force-field.** But it was fun!

**If I bungled some detail of lightsaber technology in that reply, don’t tell me. Ignorance is bliss, and honestly, it won’t change the point — a lightsaber isn’t a real sword, doesn’t behave like a sword, nor are Jedi normal people. Consequently, the fights can pretty much be whatever the director wants. If you’re looking for “realism” in Star Wars, and have zeroed in on critiquing the lightsaber fights, you’re so far down the rabbit hole, I can’t save you.

That brings me to the first point: a feature film, TV show, videogame, etc., especially one in a fictitious, secondary world, isn’t a documentary. A theatrical fight-director (or “violence designer”) and a martial arts instructor have entirely different objectives. My job is to teach people efficiency, and how to, ideally, hit the other person before they even know they’ve been attacked. A fight choreographer is trying to create action that enhances a story: the fight needs to express the character’s personality, tell us who’s good or bad, advance a narrative, etc. Obviously, I prefer to see a fight director do that with more realistic techniques – and in this article we’ll see a couple of video clips that show that – but I get that is not their job.

But, some fantasy, for all its dragons and elves, seeks to be “historicalish.” Such is the world of The Witcher, a more-or-less parallel Eastern Europe. Since the new Netflix show is a huge hit, it only made sense that I’d be asked, this time by Polygon, to analyze the fights. What follows here is an expansion and (I hope) improvement on that interview.

Now, full disclosure: I’m not a big authority on The Witcher. I’ve read the first short story collection, I played the first video game, and that’s it. So I get the general gist and the feel is sort of late medieval central-eastern Europe, with elves, etc. (The medieval history nerd in me will add that it’s a little depressing that the video game was decidedly better at capturing time and place in its visual design that the very expensive TV show, but whatevs.) In order to do the original interview I had to go watch the show, since I hadn’t seen it yet. My understanding is that Witchers are stronger and faster than normal humans, and that means that, creatively a) the show needs to demonstrate that in its fights and b) our hero should get to do things that exceed realism.

Anyway, on to the swordfights!

Geralt (in the show) is armed with a fairly short longsword, a fantasy equivalent to a form of the sword that might have existed around 1400 ad – two-handed hilt on a blade no longer, or not much longer, than a one-handed sword, creating a weapon that is suited to use in one or two hands, which means you can also use in on horseback, or, if you must, with a shield. I think the blade is still a touch short, but as fantasy swords go, it’s reasonably realistic.

What about the fight techniques themselves? Well, this seems to be a season favorite:

As does this:

In both of them you can see that they have designed a “style” for Geralt: powerful slashes, usually made after he parries (what is called a hanging parry), straight thrusts and then quick transitions to a reverse grip, often holding the sword by the forte (base of the blade), with his hand wrapped around the guard. From here, he uses thrusts and in-close slashes. He usually moves from one grip to the other in conjunction with pirouettes. But does any of that have any basis in reality?

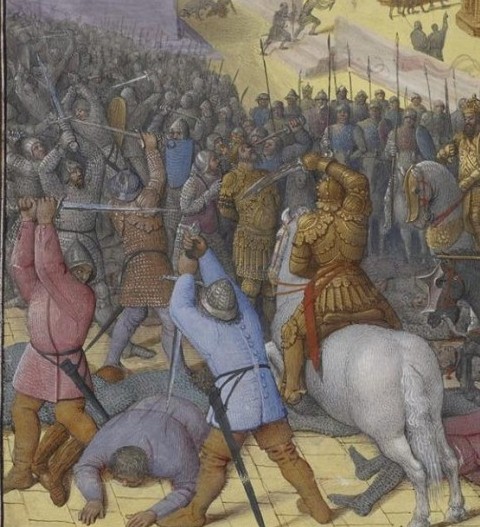

Reverse grip vs man on ground. Manuscript BNF Français 247

Les Antiquités judaïques Folio 213v Dating 1410-1420

So the hanging parry and cuts – you’ve seen that plenty and every sword or stick-fighting art uses such techniques. Likewise, one and two-handed cuts and thrusts with a sword of this size is fine.

As to the reverse grip. So, there IS some documentation for using a longsword in a reverse grip. More often this was done on horseback, where the sword was drawn when the lance broke and then just thrust into someone (and forgotten) like a giant dagger, or as a coup de-gras for a downed combatant (see the lovely battle scene to your left).

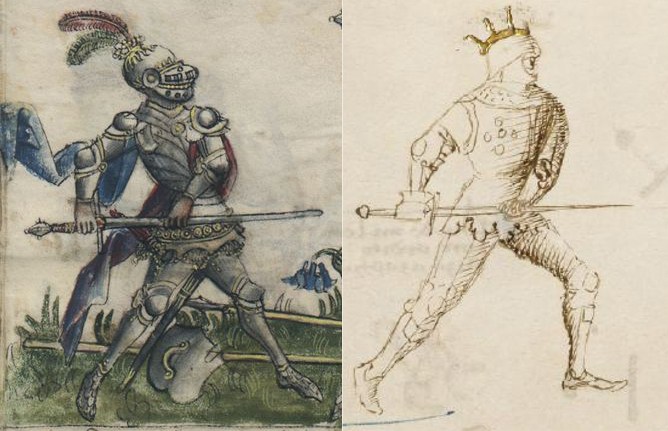

The Two-Horned Guard with a reverse grip,

shown by Fiore dei Liberi fl. late 14th c).

Note the purpose of the guard is to make the

sword strong in straight, linear thrusts.

But there are a few techniques where the longsword is actually used in a reverse grip – found primarily in 15th c German sources, and usually, only the rear hand is reversed. The earliest example, is Italian, however, where

This is Posta Bicorno (Two Horned Guard) which is closed so the point is always in the middle of the line. And what I can do with Posta Longa, I can do with this. And similarly I say for Posta di Fenestra and Posta Frontale.

That’s a bit obtuse if you don’t study the art, but basically it means that he uses this grip to create a thrusting guard that is very strong, making it difficult to displace his thrusts, while he can thrust straight through the opponent’s blow.

While rare, this isn’t a one-off, the same technique. It’s won again by Peter Falkner, a captain of the Marxbruder fencing guild in the 1480s, then crops up in fencing manuscripts 70 years later, and is even shown in non-technical artwork, such as this painting by the famed Brueghel. The purpose is always the same: strong, center-line thrusts, often used to intercept an incoming-cut.

A technique using the reverse grip from Peter

Falkner’s fencing book (1480s). Ms. KK5012 12v

The same grip in the Ars Athletica, a

vast compendium of martial arts texts,

created by Paulus Hector Mair in the mid-16th c.

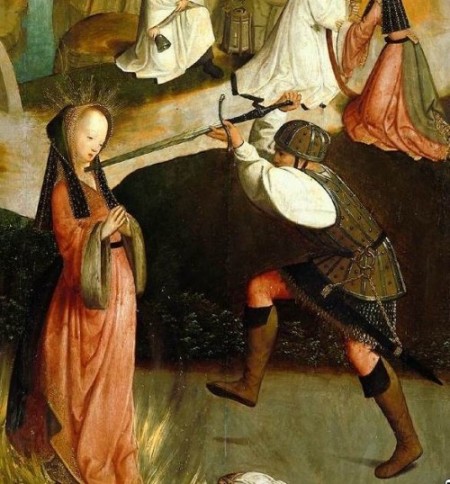

Leaving aside the brutal murder of an unarmed woman,

here we see the attack that actually comes out of

the reversed grip — an overhand thrust.

So I’m afraid, for our friend, Geralt, although there IS a reversed grip, this is probably 1% of technical material we have on medieval swordsmanship, definitely NOT something a swordsman would build a style around. It is also used rather differently as you can see described here by a pair of my American and German colleagues:

Doesn’t look very familiar to what our Witchery friend does, eh?

What’s more, Geralt periodically uses the sword in a reverse grip to slash rather than thrust, a technique that would be largely useless against the fairly heavy clothing of medieval Eastern Europe (or shown in the show). Medieval swords are sharp, but not razor sharp, nor does holding the blade in such a fashion really use the leverage of a long blade properly to cut. Even with super-strength, cutting heavy fabric isn’t really about *strength*; but rather is a combination of strength, speed, leverage, blade curvature and blade sharpness. Obviously, there is more leverage with a normal grip, rather than choking up (if you don’t understand why, ask yourself how you swing a bat to hit a line-drive vs. to bunt). Likewise, the longsword is a straight blade so no curve. While the last handsbreadth can be very very sharp, the sword overall was not a razor-blade, as the sharper the blade the more brittle its edge, meaning it will be badly damaged encountering other swords or armour. So, even if our Witcher has the strength to slice through fabric garments, choking up on the blade is a dumb reason to do so.

Consequently, I’m afraid that a central part of Geralt’s fighting style owes far more to 1980s Ninja movies than it does historical European swordsmanship.

Now, about all that blade grabbing. Gripping the blade to use the sword like a short spear is definitely a thing, and formed a central part of fighting against full plate armour. (I am just going to assume our readers KNOW that you can’t cut through plate armour with a sword, and we’ll attribute all of that armour murder in The Witcher to Gerald’s super-strength. Yeah, let’s go with Witcher Super-strength.) Blade grabs do also occur sometimes out of armour, usually either as a way to counter a weapon with superior mass like a polearm, when it might even be grabbed by the forte, right above the cross, rather than the middle.

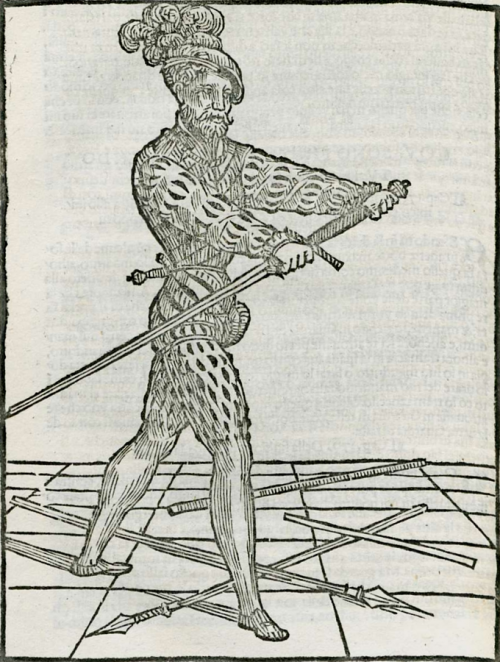

Use of the shortened sword in the anonymous German ms Gladiatoria

Using the shortened grip to close distance against

a cut. Peter Falkners fencing book, late 15th c.

Guard for defending with the two-handed sword against

polearms. Achille Marozzo, 1536. This is about as

close to the Witcher grip you are going to get.

But grabbing it ONLY by the blade, and with your hand half-wrapped around the cross. To be blunt, that’s just stupid. Really, worse than stupid – a good way to mangle your hands.

Even so, I stand by what I told Polygon:

Overall the fights are fast and furious… I suspect 15-year old Greg would have loved it! 40-something Greg… I can appreciate what they are trying to do – make Geralt’s fighting unusual and dynamic – and at least the fights are fast-paced and competent.

As I said, it isn’t the fight director’s job to be “historically accurate,” however, unless that is what the director specifically wanted. I think for the show’s purpose, the fights are fine.

Having said that, here is what some examples of real, medieval swordsmanship SHOULD look like:

You probably noticed that after one or two passes, the fight is over, which is not always desirable for a film. So here’s an example of how you can create an exciting, dynamic choreographed swordfight, with a number of film tropes (falls, throws, etc) using all historical techniques:

The take-away? This is a fantasy show, and not a “heavy” one at that; a 2020 version of Xena, with more blood and plenty more nudity. In creating Geralt, they found an actor who can sell physicality and developed a fighting style for him that has a few believable elements, plenty of flashy ones, but it is decidedly a *style* and one that nods at his supernatural abilities. I wouldn’t point to it to demo historical swordplay, but that wasn’t it’s purpose.

Addendum: What’s That on Matt Damon’s Head?

Now, HISTORICAL fiction is another kettle of fish, and one that I might tackle in a future column. Imagine, if you will, that you are watching a film on the Cuban Missile Crisis and JFK whips out his cell-phone; or perhaps in a WWII film you see a British officer walk into THE TRENCH, wearing a red-coat and shako… yet that’s what happens in films depicting the Middle Ages all of the time. Considering the reams of visual imagery and expertise that can tell us how someone dressed, what they fought with, what their homes looked like, and so forth, it’s really inexcusable to not get at least a general impression right.

As I was writing this column, the first stills from the The Last Duel, about an incredibly lurid and bloody tale of real events that occurred in the late 14th century and starring Matt Damon, Judy Comer, Adam Driver and Ben Affleck, just started to appear. Let’s just say that they don’t inspire confidence.

How so?

Do you remember those word games of “cat is to dog, as ball is to…”? Let’s play one:

This:

Yes, Virginia, that is a

bona-fide, 1980s mullet

is to this:

or this:

As this:

is to this:

Let’s just say I suspect that fidelity to historical swordsmanship is NOT going to be a priority! (yes, I sense a future column….)

In two weeks we come back for what was supposed to be my second column, with someone for whom such fidelity IS a priority, and hopefully an explanation as to why.

In all fairness to the mullet, once you reach a certain age, it does feel like the ’80s were 600 years ago. Or maybe it’s just my body that feels that way. 🙂

Wow, that was thorough and enlightening. Great post! I’ll still enjoy the Witcher for its story and soundtrack.

Glad you enjoyed! As to enjoying the show — you should! It’s good popcorn material.