An Ode to Robert E. Howard, from a Rogue Blades author

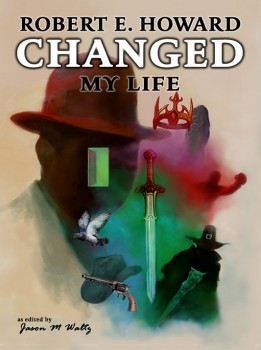

This excerpt from author Cecelia Holland is taken from her essay for the upcoming book, Robert E. Howard Changed My Life, from publisher Rogue Blades Foundation.

This excerpt from author Cecelia Holland is taken from her essay for the upcoming book, Robert E. Howard Changed My Life, from publisher Rogue Blades Foundation.

You have to understand, being a girl in the 1950s was a complete dead end. I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t play Little League or football; I couldn’t even play full court basketball. I couldn’t take shop instead of home ec. I couldn’t ride in the rumble seat of my uncle’s new car because I was too young, although my male cousin who was a week older than I got to ride in it a lot. When I asked for an erector set for Christmas, they laughed and gave me a doll.

I was gently dissuaded from thinking about having a real life when I grew up, since I would of course find some nice man to marry me and take care of me and I would spend my life raising children and washing dishes (and probably drinking like a fish, as all my aunts did, drowning their personal ambitions), so why should I even bother with college?

I did have one aunt (I had many aunts) who did have a career, for which she was broadly pitied.

I escaped. Robert E. Howard helped me escape.

|

|

|

When I was around 12 in the basement of a friend’s house, I found an old copy of Weird Tales (I’m not sure about the magazine, but it must have been a pulp) and read my first Conan story. I loved it; not just for the action—I was a big fan of action stories—but because Conan was a barbarian. He was outside the settled boundaries of propriety and decorum. He made himself up as he went along. He wasn’t a woman, but I was already so sunk into the abhorrence of womanhood that that actually worked in his favor. Conan was outlaw fiction. I knew my own path forward was to be an outlaw.

(I’ve given some thought lately to the notion I might have been suffering from some sort of gender dysphoria. But that’s another story.)

(I’ve given some thought lately to the notion I might have been suffering from some sort of gender dysphoria. But that’s another story.)

In school, of course, we were supposed to read literature, and I liked Kipling and I loved Bulfinch’s mythology, but from then on I looked for all the outlaw fiction I could find. Harold Lamb became a particular favorite, but my heart belonged to Conan. To me, he didn’t look like Arnold Scwarzenegger, more like my dad, with bigger muscles.

Being on the outside was not such a bad thing. Freedom was being a barbarian.

I was trying to write my own stories, not well. Everything seemed to come out flat and boring. But when I tried to imitate Howard’s grandiose epic prose, it got even worse, phony and pedantic. I didn’t dare show any of this to anybody else; a blow from Conan’s sword was no less wounding than being laughed at. I didn’t know it, would not know for years, but I was struggling for my own voice.

Howard’s magnificent overreach of words worked in the Conan stories because of the shimmer of magic. But I didn’t want magic. I wasn’t sure what I wanted. I was a teenager in the 50’s. Everybody was telling me to shut up, sit down and listen. Conform. Be who I was told to be, a girl in a dress. What mattered was what men thought of me.

As Valeria says, in Red Nails—

“Why won’t men let me live a man’s life?”

“That’s obvious!” [Conan replies]. Again his eager eyes devoured her.

I could live without devoured, metaphorically or otherwise. Maybe I would be a nun.

Cecelia Holland has been writing all her life, mostly historical fiction, but also fantasy and science fiction. She lives in Northern California with her children and grandchildren, writing and gardening, and teaches writing two days a week at Pelican Bay State Prison.

Ty Johnston is vice president of the  Rogue Blades Foundation, a non-profit organization focused upon bringing heroic literature to all readers. A former newspaper editor, he is the author of several fantasy trilogies and individual novels.

Rogue Blades Foundation, a non-profit organization focused upon bringing heroic literature to all readers. A former newspaper editor, he is the author of several fantasy trilogies and individual novels.

[…] E. Howard (Black Gate): When I was around 12 in the basement of a friend’s house, I found an old copy of Weird Tales […]

[…] E. Howard (Black Gate): When I was around 12 in the basement of a friend’s house, I found an old copy of Weird Tales […]