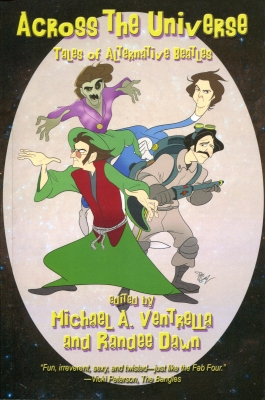

A Lasting Exploration of What the Beatles Mean: Across the Universe: Tales of Alternative Beatles edited by Michael A. Ventrella and Randee Dawn

Although the Beatles, as comprised of John, Paul, George, and Ringo, only existed as a band from August 1962 until April 1970, they left an indelible mark on the music and culture of the world that is constantly being discovered, explored, and reinvented. One of those reinventions occurred in 2019 with the release of the film Yesterday, in which singer Jack Malik discovers he is one of the few people in the world who remembers the Beatles and builds a career out of recreating their songs. Even before that film was released, however, editors Michael A. Ventrella and Randee Dawn were at work creating the anthology Across the Universe: Tales of Alternative Beatles.

At lunch in the executive dining room of Black Gate Tower a couple of weeks ago, our esteemed editor and I were finishing our desserts (wild honey pie for me, Savoy truffle for him), when he asked my opinion of Yesterday. I described what I liked about it, what I felt could have made it better, and explained that I viewed a world without the Beatles or Coke as essentially dystopian. I told him why the alternative ending would have improved the film and, at the same time, opened up other questions that it hadn’t addressed.

Two days later I was summoned into the presence of the giant, floating holographic head that gives Black Gate writers their assignments, and presented with a copy of Across the Universe. Our conversation at lunch had been sounding me out for my knowledge of all things Beatle.

Jody Lynn Nye has cast the Fab Four as powerful elemental wizards and follows the adventures of George, the water mage, as he strikes out on his own and finds himself face-to-face with a powerful enemy. The story explores the difficulties of making it on your own when you’re used to working in a group, but also points out how experiences continue to inform a person’s actions. Nye also looks beyond Harrison’s career with the Beatles and even his solo career for her source material.

Keith R.A. DeCandido has also cast the four in a traditional fantasy setting, assigning them the roles of bard, wizard, cleric, and barbarian. DeCandido tells the story of the adventurers’ breakup as a flashback, contrasting what is believed by what the four know to have actually happened, bringing in oblique references to characters in Beatles songs.

Carol Gyzander’s title, “Deal with the Devil,” hints at the outcome of her story about the Beatles in 1960 with a fifth member, Chas, sitting in for Stu Sutcliffe. When a couple of kids from forty years in their future reach through time to the Beatles, the band is given a hint about the direction that Black Sabbath will take rock, and gets visions of the size crowds Black Sabbath will play to, without an understanding of their own future.

An alternative version of George comes from Sally Weiner Grotta, who has him answer an invitation from Richard Nixon in late 1969. Nixon hopes to use the popularity of the Beatles to help him reach out to America’s protesting youth. What he gets is a George Harrison intent on bringing enlightenment to Richard Nixon through the use of Transcendental Meditation.

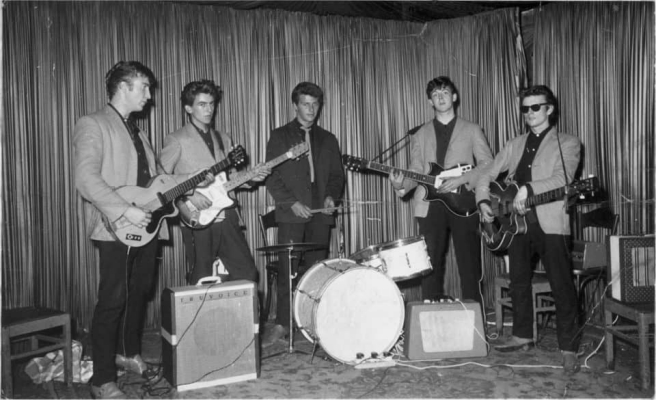

The Beatles: John Lennon, George Harrison, Pete Best, Paul McCartney, Stu Sutcliffe

Brenda W. Clough also takes a look at George, focusing on his desire to achieve a sense of nirvana, and tying his ultimate success in to the 1999 attack on the Beatle at his home. Clough reveals a far deeper and more sinister reason for the attack than the home invasion it was in our own world, with an interesting tie in to science fiction.

Eric Avedissian offers an alternative history where the Beatles broke up in Hamburg in 1961. Twenty-one years later, a down-on-his-luck John Lennon tries to put the band back together only to be met with ambivalence by the other Beatles. Told in a flashback, the ultimate outcome, if not the details, are known to the reader and undercut the effectiveness of the story.

The idea that a John Lennon who didn’t make it big in the Beatles would be a failure is also explored in Christian H. Smith’s “Through a Glass Onion,” in which a John Lennon living in 1988 is given a glass onion paperweight that shows him what life in our timeline would be like. Working on his third marriage, Lennon grasps at the idea that it isn’t too late to achieve that dream, despite the lack of interest from a Paul McCartney who is successful in insurance. The story ends on a hopeful note for Lennon.

All too often in theme anthologies, many of the authors rely on “high concepts” based on the theme in which the story doesn’t stand up to any real rational scrutiny, and often even lacks any real plot to go along with the concept. In Across the Universe, Bev Vincent casts the Beatles as members of a Canadian hockey team improbably going up against other Canadian hockey teams also made up of British band members. While these may make for entertaining vignettes, the reader is left wondering how the very real Beatles wound up in these situations.

R. Jean Mathieu offers a very short piece in which John Lennon’s martyrdom results in a new religion, but when one of its adherents, Richard Francis, finds himself questioning how the religion follows John’s teaching, he is decried as an heretic. The story is, once again, a high concept that does feel fully fleshed out in the brief span the author has.

An easy form of humor in many of the stories is the wink to the reader in the titles and lyrics of Beatles songs that find their way into the stories. This isn’t particularly a negative thing, and the Beatles themselves were not above self-referencing their own lyrics (see for instance “Glass Onion,” or John Lennon’s solo diatribe “How Do You Sleep”). It only becomes a problem when a story is more full of allusions than it is of original work, as is the case in David Gerrold’s “The Fabtastic Four,” which replaces the members of the Fantastic Four with the final lineup of the Fab Four, or Gordon Linzner’s “The Hey! Team,” which casts the quartet as a version of “The A-Team.”

The book is full of other stories which imagine the Beatles as other famous foursomes. Gregory Frost’s “A Hard Day’s Night at the Opera,” as the name suggests, is a mash-up of the opening sequences of the Beatles’ first film and the Marx Brother’s sixth film, although the characters are more true to the Marxes than the Beatles. Gail Z. Martin’s “The Walrus Returns” offers the Beatles as versions of the Scooby Doo gang looking for the Mersey Monster and pirate ghosts. The most effective recasting of the Beatles is by Ken Schneyer, who starts out by depicting them as the Three Musketeers, but eventually turns the story into a contemplation of reality vs. legend.

One story which doesn’t use the obvious Beatles quote is Patrick Barb’s “When I’m #64,” which could easily have quoted the opening lines from the Beatles song “She Said She Said.” In this story, Paul McCartney dies over and over again. Barb looks at the way Paul’s inability to remain dead impacts those around him, particularly John and Linda, and Barb offers an unforeseen ending as Paul comes back to life one last time in the story.

Another take on Paul being dead is Lawrence Watt-Evans’ “Paul Is Dead.” In his story, Fred Eberhart travels between realities to find an alternative version of Paul to take his place so there can continue to be original Beatles music after 1966. Although Eberhart gets his wish, he isn’t as successful as he had hoped, as Paul comes to terms with working with a different and more mature John Lennon than the one he had known in his own 1961.

Alan Goldsher takes the Paul is dead rumor in a different direction, offering a story more inspired by Frankenstein and only tangentially related to the Beatles in that the narrator is a zombie Paul writing to a zombie John. Just as Goldsher notes that his Dr. Frank Victor had little use for the Beatles, it seems the story could have been written without invoking the Fab Four.

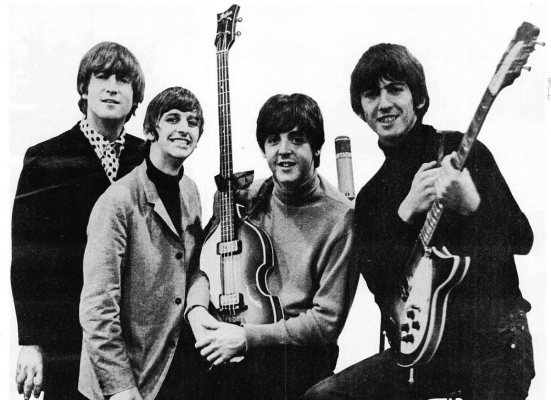

The Beatles: John Lennon, Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney, George Harrison

Beth W. Patterson’s story opens interestingly with the idea that instead of the Beatles from Liverpool leading a British invasion, there is a band, Les Écrevisses, from Louisiana leading a Cajun invasion. Unfortunately, rather than exploring what a world in which Cajun and zydeco are the primary forms of pop music, the story veers into a monster tale as the band is sent in search of a loup garou that is damaging the tabasco crop.

Allen Steele’s “Come Together” doesn’t deal with the Beatles at all, but rather four AIs on an interstellar spacecraft that have been programmed to emulate the Beatles’ speech patterns after the AIs were named for the members of the band. Unfortunately, as the AIs develop sentience, they also begin to emulate the Beatles’ personalities, including the final years of their collaboration as they became less willing to cooperate, thereby endangering the success of the mission. The remove from the actual Beatles makes Steele’s story one of the strongest in the volume.

Another futuristic tale is Cat Rambo’s “All You Need,” set in a Seattle after a climate apocalypse when a barter system exists and people live in fear of the vicissitudes of their climate. When a boy brings four robots representing the Beatles into a trading post, he suddenly finds himself with a lot of leverage, but the behavior of the robots, particularly Paul, leads him to an understanding of empathy rare in the cut throat world in which he lives.

Another, more traditional apocalyptic tale is Matthew F. Amati’s “Apocalypse Rock,” which envisions a post-Cuban Missile crisis world in which bands, mostly playing brass instruments with drums, travel the barren landscape to provide entertainment for warlords. As with many of the higher concept stories, this one requires a higher level of suspension of disbelief as the band, made up of Jean-Paul, Jorge, and Wrongo, are Americans rather than British. Amati has created an interesting setting, which would have worked better if he hadn’t being trying to work in Beatles references or jokes on other bands.

Pat Cadigan offers what may be the most personal story in the anthology with a narrator who is clearly based on herself, although it is always problematic to read too much into an author’s fiction. Cadigan’s character is visited by the spirit of a friend who insists the two have to travel through time to save the Beatles, although it is never clear what they are being saved from. Instead, the story offers Cadigan’s character and her friend to vicariously become John and George during the infamous August 12, 1966 concert at the Cleveland Stadium that had to be stopped when the fans rushed the stage.

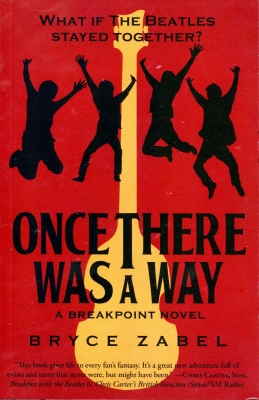

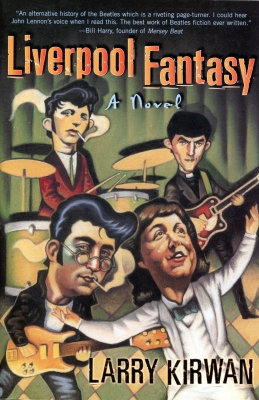

Across the Universe opens and closes with reprint stories: Spider Robinson’s “Rubber Soul” and Gregory Benford’s “Doing Lennon,” both classics in the alternative Beatles genre, which also includes Bryce Zabel’s Sidewise Award winning novel Once There Was a Way, Stephen Baxter’s “The Twelfth Album,” Ian R. MacLeod’s “Snodgrass,” and Larry Kirwan’s Liverpool Fantasy. It is quite possible that some of the stories in Across the Universe will join these stories as lasting explorations of what the Beatles and their work mean.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Dont’ forget “With a Little Help from Her Friends” by Michael Bishop, F&SF February 1984…