Back to the Books for the Theater of the Mind

I came to Old Time Radio late in life. My parents were born in 1940 and 1942, respectively. They remembered radio shows from their childhood, but the advent of television made more of an impact on them. During my teen years, one of our local UHF stations briefly picked up reruns of the jazz noir detective series Peter Gunn (1958-1961) in the mid-1980s and I was instantly hooked. A set of Peter Gunn episodes on VHS followed in 1989 from Rhino Records. Before long, I was hunting for Henry Kane’s well-written paperback tie-in and the goofy Dell Comic (where Pete tracks down villains trafficking in counterfeit collectible postage stamps). 2002 would bring the first DVD sets of Peter Gunn. By the time the entire series was on DVD, so was its companion series, Mr. Lucky (1959-1960); and then I discovered the imitation series, Johnny Staccato (1959-1960) which successfully blended concepts from both series before adding a healthy dose of angst-ridden method acting to the mix.

I came to Old Time Radio late in life. My parents were born in 1940 and 1942, respectively. They remembered radio shows from their childhood, but the advent of television made more of an impact on them. During my teen years, one of our local UHF stations briefly picked up reruns of the jazz noir detective series Peter Gunn (1958-1961) in the mid-1980s and I was instantly hooked. A set of Peter Gunn episodes on VHS followed in 1989 from Rhino Records. Before long, I was hunting for Henry Kane’s well-written paperback tie-in and the goofy Dell Comic (where Pete tracks down villains trafficking in counterfeit collectible postage stamps). 2002 would bring the first DVD sets of Peter Gunn. By the time the entire series was on DVD, so was its companion series, Mr. Lucky (1959-1960); and then I discovered the imitation series, Johnny Staccato (1959-1960) which successfully blended concepts from both series before adding a healthy dose of angst-ridden method acting to the mix.

I couldn’t stop there of course, not with gray market sets of Peter Gunn‘s progenitor, Richard Diamond (1957-1960) and Mr. Lucky‘s successor, Dante (1960-1961) circulating among collectors. Eventually, I discovered a terrific, but nearly forgotten television adventure series, Hong Kong (1960-1961) and reached back to find Dante had actually preceded Mr. Lucky via an earlier series, Dante’s Inferno (1956). Having reached the end of the line for the uniquely sophisticated and stylish Golden Age of Television detective and adventure series that appealed most to me, I decided to venture into the largely unknown waters of Old Time Radio.

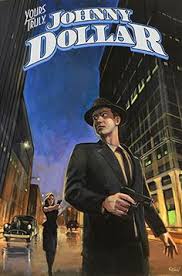

I soon plunged from cheap MP3 CDRs deep into the pricey remastered deluxe sets from Radio Archives. I soon thrilled to countless episodes of the first iteration of Richard Diamond (1949-1953) for radio as well as the greatest detective series of them all, Johnny Dollar (1949-1962). After that, Tommy Hancock recommended I sample the adventure series that would quickly become my favorite dramatic series in any medium, Rocky Jordan (1945-1951). I’ve been commuting to work daily again after many years of life on the road as a contractor. Old Time Radio, the Theater of the Mind, has become an essential part of each morning and evening, particularly during daylight savings when I leave for work in pitch darkness and return home the same way 12 hours later.

Having collected vintage paperback originals like Henry Kane’s aforementioned Peter Gunn novel, Albert Conroy’s (Marvin Albert under one of his many guises) rather sleazy Mr. Lucky novel, and Frank Boyd’s entertaining Johnny Staccato novel, it was with some trepidation I approached recent efforts to bring the Theater of the Mind back to the printed page courtesy of Alan King (no, not that Alan King as Amazon initially suggested, but rather a self-published writer also known alternately as Alan Drew Thompson and Ricardo Tantos) and his curious and completely unauthorized Richard Diamond collection.

Having collected vintage paperback originals like Henry Kane’s aforementioned Peter Gunn novel, Albert Conroy’s (Marvin Albert under one of his many guises) rather sleazy Mr. Lucky novel, and Frank Boyd’s entertaining Johnny Staccato novel, it was with some trepidation I approached recent efforts to bring the Theater of the Mind back to the printed page courtesy of Alan King (no, not that Alan King as Amazon initially suggested, but rather a self-published writer also known alternately as Alan Drew Thompson and Ricardo Tantos) and his curious and completely unauthorized Richard Diamond collection.

This is actually just a slim anthology of two of King’s Richard Diamond short stories set in 1948 coupled with a reprint of a completely unrelated detective story featuring an original character created by King/Thompson/Tantos. King’s Diamond bears little resemblance to the television detective played by David Janssen and even less to the radio detective voiced by Dick Powell. The pair of stories are highly derivative and completely lacking in any sign of editing or even proofreading. They could have easily been about any generic hard-boiled detective.

Moonstone Books editor/publisher Joe Gentile has much to answer for in the world of New Pulp. He may not have coined the phrase, but he certainly laid the groundwork for the publishers who have followed in his wake mixing public domain characters and licensed properties with original works in the classic mode. Moonstone found a winning formula coupled with quality product and a business model that not only succeeds, but prospers in niche publishing. Whether he intended it or not, Gentile has become the Godfather of New Pulp and served as a mentor to those who followed in his wake. The ones that didn’t pay attention likely didn’t survive.

Moonstone Books editor/publisher Joe Gentile has much to answer for in the world of New Pulp. He may not have coined the phrase, but he certainly laid the groundwork for the publishers who have followed in his wake mixing public domain characters and licensed properties with original works in the classic mode. Moonstone found a winning formula coupled with quality product and a business model that not only succeeds, but prospers in niche publishing. Whether he intended it or not, Gentile has become the Godfather of New Pulp and served as a mentor to those who followed in his wake. The ones that didn’t pay attention likely didn’t survive.

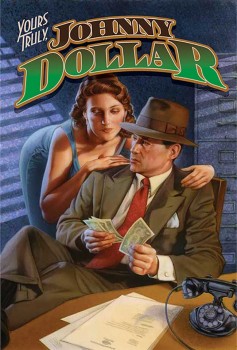

Moonstone’s first foray with Johnny Dollar, the “freelance insurance investigator with the action-packed expense account,” was in the form of a humble graphic novel over 15 years ago. That increasingly rare comic adaptation has been reprinted in the hardcover edition of Moonstone’s new prose anthology. As expected, Gentile has assembled a stellar collection of talent who succeed in delivering faithful well-written pastiches of the radio series. This book has not received the attention it deserves and is worth every penny. The stories by Eric Fein, Ron Fortier, Tommy Hancock, Bobby Nash, Gary Phillips, Barry Reese, Joshua Reynolds, and Joe Gentile himself are uniformly excellent. The collection is highly recommended.

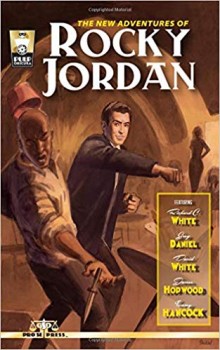

Tommy Hancock and his Pro Se Press and Pulp Obscura imprints have proven to be the most faithful of Gentile’s apprentices. Likewise, the Pro Se Press and Pulp Obscura catalogs have grown to very nearly match Moonstone in terms of quality product and reverent fidelity to classic properties such as Rocky Jordan. While Gentile, a reserved figure content to stay largely in the background, strikes a successful balance between bohemian artist and canny businessman; Hancock follows (like Ron Fortier of Airship 27 Publications) the Stan Lee model of infectious hyperbole that makes readers feel they are Close Personal Friends to the editor/publisher and therefore feel an even greater affinity for their works.

Tommy Hancock and his Pro Se Press and Pulp Obscura imprints have proven to be the most faithful of Gentile’s apprentices. Likewise, the Pro Se Press and Pulp Obscura catalogs have grown to very nearly match Moonstone in terms of quality product and reverent fidelity to classic properties such as Rocky Jordan. While Gentile, a reserved figure content to stay largely in the background, strikes a successful balance between bohemian artist and canny businessman; Hancock follows (like Ron Fortier of Airship 27 Publications) the Stan Lee model of infectious hyperbole that makes readers feel they are Close Personal Friends to the editor/publisher and therefore feel an even greater affinity for their works.

Hancock’s ever-present fedora highlights both his self-deprecating humor and endearing eccentricities. I mention these personal traits because these sometimes larger-than-life personas follow, as Stan Lee did before them, the example (though happily not the sartorial style) of Hugh Hefner. Their readership then subconsciously views the publisher’s persona as synonymous with a desirable quality publication to the extent that their every email or press release or convention appearance successfully reinforces this association. In this sense, the Big Three of New Pulp (Moonstone, Airship 27, Pro Se/Pulp Obscura) have carved unique identities despite sometimes sharing properties and talent between one another. Gentile, Hancock, and Fortier (as noted above) also regularly turn up contributing to one another’s publications which further engenders reader loyalty and identification with the New Pulp brand. The synergy this imparts serves both Johnny Dollar and Rocky Jordan well in their 21st Century revivals.

Rocky Jordan gives Pulp Obscura its best looking title yet with a stunning cover that recalls both vintage Ian Fleming and 1940s pulp. Hancock threatens readers with potential crossovers with other properties in the future, but the book itself gives fans of the series what they most desire: good stories that faithfully recapture the spirit of the radio series. Greg Daniel, James Hopwood, David White, and Richard C. White deliver the goods in post-war Cairo with the authentic feel of not only the radio series, but vintage Warner Bros. programmers of the era.

Public domain revivals can be a dicey experience for the reader particularly in a market where Lulu and CreateSpace allow for terribly low standards of professionalism (if any at all) to prevail. The examples of the Big Three of New Pulp set a standard for quality writing, design, and marketing that shows how niche markets such as Old Time Radio properties can still remain viable and free of the tarnish of cynical exploitation. “Look for the seal” was a famous slogan of the past. The New Pulp imprints highlighted here have done their very best to turn their brand into a mark of quality.

William Patrick Maynard is a writer and film historian. His commentaries have appeared on releases from MGM, Shout Factory, and Kino-Lorber. He is the authorized continuation writer for the Sax Rohmer Literary Estate and is the author of new Fu Manchu thrillers for Black Coat Press.

I’ve been watching a lot of Peter Gunn lately (I discovered that it was on my Amazon Prime) and I’m enjoying it quite a bit. I think it falls a little short of being an outright classic because of Craig Stevens – he’s ok, but lacks that extra bit of juice that would have kicked the show to another level.