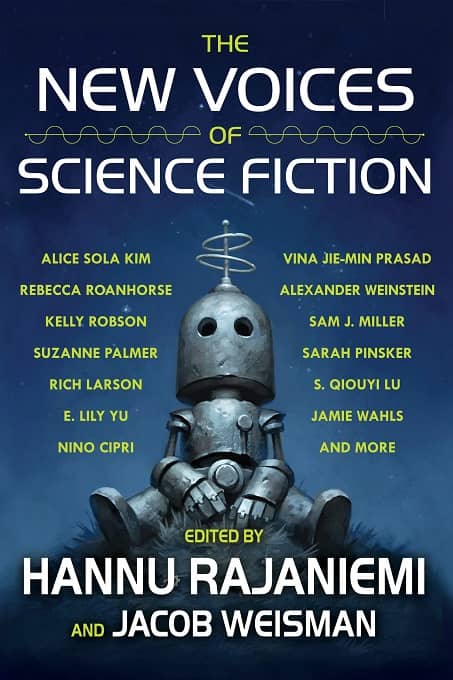

Stories That Work: “Toppers” by Jason Sanford, and “Strange Waters” by Samantha Mills, from The New Voices of Science Fiction

|

Cover by Matt Dixon

If I consider types of stories as a Venn diagram, two of the circles are “entertaining stories” and “moving stories.” They overlap but a large number of stories are one but not the other.

By “entertaining,” I mean that the situation, characters, events and writing are sufficiently distracting that I fall into the story and forget I’m reading. When I get to the end I feel my time was well-spent, but I’m not particularly changed by the experience. The story was fun. It’s the reading equivalent of watching The Last Starfighter. A great example of entertaining works I’ve read lately were Martha Wells’ The Murderbot Diaries.

A “moving” story gets to me emotionally/intellectually at the end. The writing may also be entertaining (remember that the circles overlap), but how I feel when I walk away is different. I’m thoughtful, emotional even. The story changed me. Saving Private Ryan or Schindler’s List are films that I’d say were “moving.” By my definitions, though, they weren’t “fun.” I can say a lot about those two stories, but I wouldn’t describe them as “entertaining” without a few caveats. Keye’s Flowers for Algernon moved me, as did Willis’s Lincoln’s Dreams and Leiber’s “A Pail of Air.”

Identifying a story as “entertaining” or “moving” is not a quality judgement. Great stories come from either circle, and some of our best stories are both. I found that Robert Heinlein often straddled the two camps. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is a good example at novel length, but he could be entertaining and moving when writing short, too, as he was in “The Green Hills of Earth” or “All You Zombies.”

This is a longish lead in to the two stories from my recent reading in the Weisman/Rajaniemi edited The New Voices in Science Fiction that both entertained and moved me.

The first, “Toppers,” by Jason Sanford, describes an in-the-midst-of-an-apocalypse New York City, where residents live in skyscrapers’ upper stories to avoid “the mist,” a toxic, atmospheric stew that not only kills an unprotected person, but drives them insane if they look into it. The narrator, a young girl who is referred to as “Hanger,” lives in a “slug,” a hammock roped to the outside of the Empire State Building. She works as a “mist scout,” a job that involves an air suit and the ability to walk through the rubble of New York City blindly.

Sanford’s brilliance is how he stitches together a vivid setting (the mist’s qualities grow stranger and more profound the deeper you go in the story), the dire adventure that events push Hanger into, and her personal journey. Good writing shares much with successful juggling. How many balls can you keep in the air and make it look effortless? If Sanford juggled, you’d say he has quick hands, a good eye, and preternatural coordination.

I can’t share what moved me in the story without spoiling the plot, but I can tell you that Hanger’s experience of the New York she lives in contrasted to the New York that once was hit all my “like” buttons at once. Science fiction transports readers to unfamiliar places and make them feel real. Sanford nails it in this outstanding piece.

Another title that soared in New Voices in Science Fiction, and in the running for the strongest tale in the collection, was Samantha Mills’ “Strange Waters,” where she managed to pack an epic into a short story. I’d never read any of Mills’ stories before this one, but she hooked me from the opening (you’ll see what I did there in a second):

Fisherwoman Mika Sandrigal was lost at sea. She knew where she was in relation to the Candorrean coastline and how to navigate back to her home city, Maelstrom. She knew the time of day. She knew the season. She knew the phase of the moon and the pattern of the tide.

She did not know the year.

Similar to several other pieces in the anthology, “Strange Waters” touches on family issues and time travel. Poor Mika went fishing but was caught in a time current. When she returns to shore, it’s a different year, and she has lost her family. Being a time traveler in a world where time travel is possible and well-known presents surprising challenges, and also set up one of my favorite passages. She could stay on the comfort of shore, but, as Mills says, “. . . it wasn’t worth the risk. It was only a matter of time before Mika drew the attention of someone worse than a researcher. Like a politician. Or a librarian.”

Mika’s quest struck me as strongly as Odysseus’s. In an alien setting, Wells thrust an ordinary fisherwoman into extraordinary circumstances to reveal a hero.

I don’t cry often when I read fiction, but I did at the conclusion of “Strange Waters.”

The New Voices in Science Fiction entertained me consistently, and moved me several times. Weisman and Rajaniemi picked winners for the table of contents.

And, oh, if you want to know what I thought was the most “fun” piece, try Suzanne Palmer’s “The Secret Life of Bots.” Somebody complained to me recently that Hugo and Nebula winners are too literary or political lately to be entertaining. That’s not the case with this 2018 Hugo Award winning novelette, and I suspect my complainer hasn’t read as deeply into recent award winners as his comment suggested.

James Van Pelt lives in western Colorado. He has published five collections of short fiction — including Strangers and Beggars (2002), The Last of the O-Forms & Other Stories (2005), and The Experience Arcade and Other Stories (2017) — and two novels, Summer of the Apocalypse (2006) and Pandora’s Gun (2015), all with Fairwood Press. His last Stories That Work article for us looked at fiction by Rebecca Zahabi and Edward Ashton.

[…] BLACK GATE, James Van Pelt showcases Jason Sanford’s and Samantha Mills’ tales from the book to […]