Silas P. Cornu’s Dry Calculator

Digging through the vast, deep landscape of popular culture is very much like being a working paleontologist. Fragments of bones are everywhere, both on the surface and accessible through spadework. Unbroken samples are rare finds, interesting enough in and of themselves but truly valuable only if put into context.

Also as in paleontology, trying to create a proper history grows exponentially more difficult every time a new site is opened. The older metaphor of an evolutionary tree of life that leads to a single branch labeled Homo is now obsolete; modern practitioners see more of a bush with a tangle of branches whose origins are obscure.

The origin of science fictional ideas matches this entropic march toward disorder. Fans of SF once proudly hailed the writers in the field for coming up with fantastic ideas, notions, gadgets, and futures that could be boasted about to their snobbish mundane friends. Years of historical research into the subject make me wonder sometimes if any sf writer ever had a truly original idea.

Take Isaac Asimov, for example. His famed short story, “The Feeling of Power,” appeared in the February 1958 issue of If. Wikipedia has a compact one-sentence summary.

In the distant future, humans live in a computer-aided society and have forgotten the fundamentals of mathematics, including even the rudimentary skill of counting.

Original? It’s been lauded as such. But he was anticipated by exactly 60 years.

Not much is known about Henry A. Hering (1864-1945) other than his being British. His first story seems to be “Silas P. Cornu’s System” in the April 1896 Cassell’s Magazine. Cornu, an inventor, sells the inhabitants of Tontine City, Dakota [sic], collapsible housing so they merely have to flatten and then unfold their houses in the case of a tornado. This works fine once, but not the second time when the tornado reverses tracks.

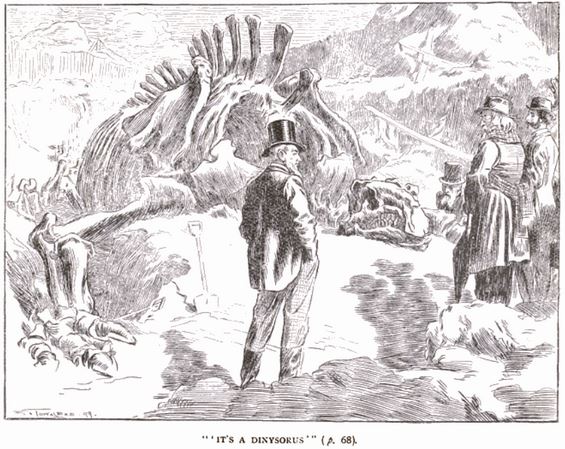

Hering only wrote eight more stories in the 1800s but three more were Cornu tall tales. “The Adventures of Pharaoh” has a mummy coming back to life and “Silas P. Cornu’s Diving Rod” finds everything from a full skeleton of a “Dinysorus” to a well of copying ink but not the gold it was looking for.

The second of the series was “Silas P. Cornu’s Dry Calculator,” Cassell’s Magazine, February 1898. It’s apparently never been anthologized, although it was included in Hering’s impossible-to-find collection Adventures and Fantasy, which appeared in 1930, long after his writing career was over.

I’m going to borrow and shorten Everett F. Bleiler’s precis of the story, also set in the American West.

[Cornu] builds a calculator that will add and multiply … [filling] a current need in Athens, since the town, considering itself a new version of the ancient Greek city, has devoted its entire educational establishment to Greek and Latin classics, with total disregard for mathematics.

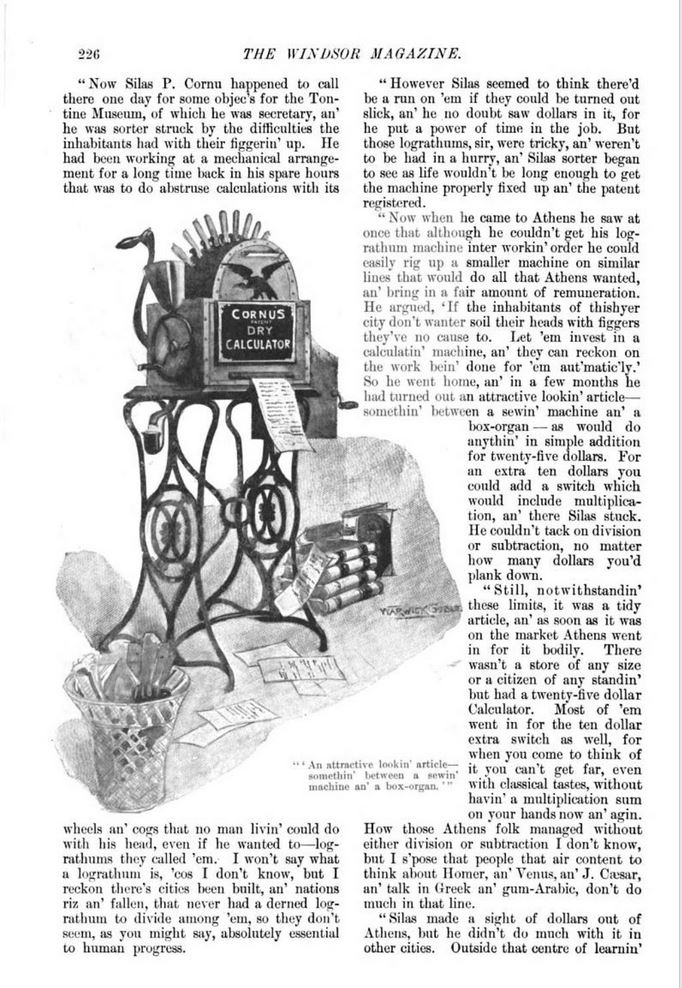

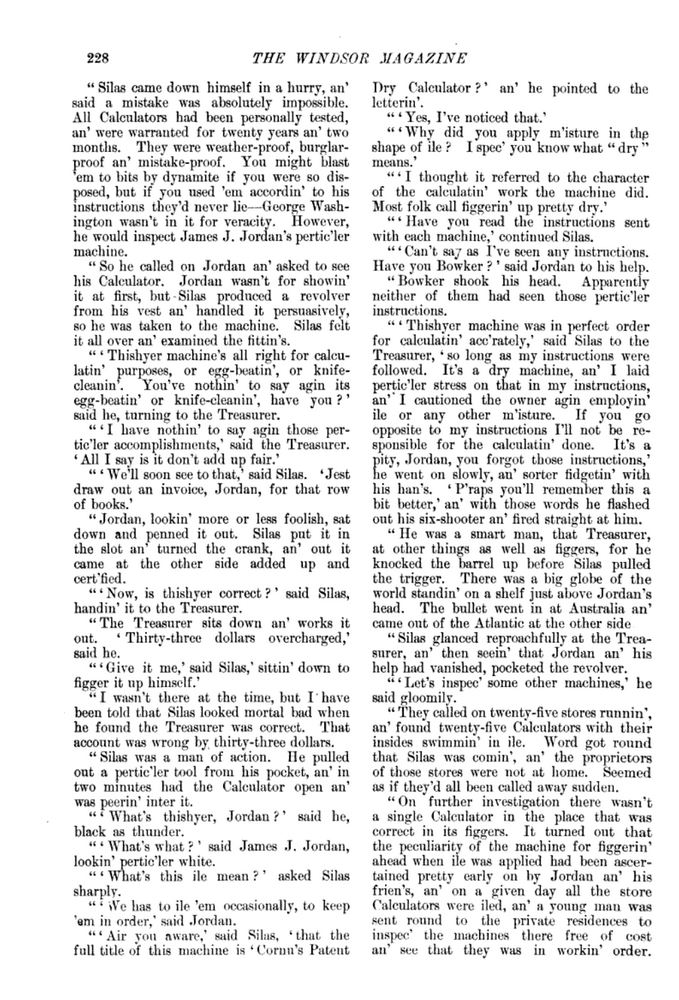

Look at that calculator below and tell me it doesn’t qualify for a proto-robot. It practically leers.

The calculator has one flaw, which is exploited by wily town merchants. But then along comes someone who knows his numbers. You might say that this is the very first story about computer crime.

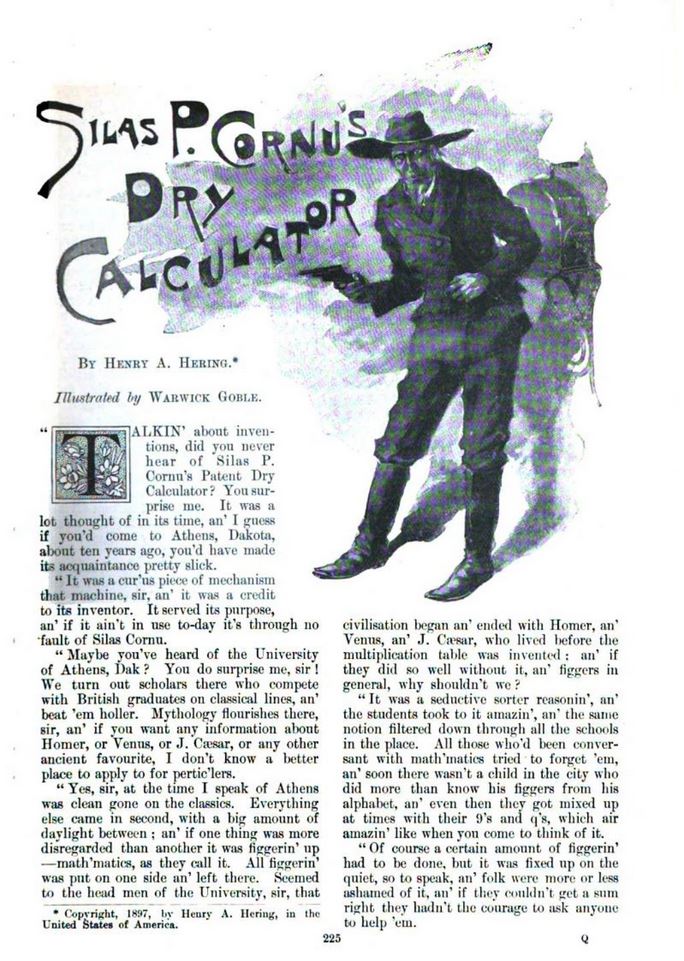

Cassell’s profusely illustrated its stories, a rarity at the time. Artist Warwick Goble was a rising star in the art world at the time, with commissions from all the major English magazines. He had recently illustrated “War of the Worlds'” first appearance in Pearson’s Magazine. He made Silas the meanest-looking inventor of all time, too.

Since I don’t know how small a screen you’ll be reading this on, I’ll post the original pages and give a transcript showing the complete text, page by page.

SILAS P. CORNU’S DRY CALCULATOR

BY HENRY A. HERING (1864-1945)

Illustrated by WARWICK GOBLE

From Cassell’s Magazine, February 1898TALKING about inventions, did you never hear of Silas P. Cornu’s Patent Dry Calculator? You surprise me. It was a lot thought of in its time, an’ I guess if you’d come to Athens, Dakota, about ten years ago, you’d have made its acquaintance pretty slick.

“It was a cur’us piece of mechanism that machine, sir, an’ it was a credit to its inventor. It served its purpose, an’ if it ain’t in use to-day it’s through no fault of Silas Cornu.

“Maybe you’ve heard of the University of Athens, Dak? You do surprise me, sir! We turn out scholars there who compete with British graduates on classical lines, an’ beat ’em holler. Mythology flourishes there, sir, an’ if you want any information about Homer, or Venus, or J. Cæsar, or any other ancient favourite, I don’t know a better place to apply to for pertic’lers.

“Yes, sir, at the time I speak of Athens was clean gone on the classics. Everything else came in second, with a big amount of daylight between; an’ if one thing was more disregarded than another it was figgerin’ up- math’matics, as they call it. All figgerin’ was put on one side an’ left there. Seemed to the head men of the University, sir, that civilisation began and ended with Homer, an’ Venus, an’ J. Cæsar, who lived before the multiplication table was invented; and’ if they did so well without it, an’ figgers in general, why shouldn’t we?

“It was a seductive sorter reasonin’, an’ the students took to it amazin’, an; the same notion filtered down through all the schools in the place. All those who’d been conversant with math’matics tried to forget ’em, an’ soon there wasn’t a child in the city who did more than know his figgers from his alphabet, an’ even then they got mixed up at times with their p’s and q’s, which air amazin’ like when you come to think of it.

“Of course a certain amount of figgerin’ had to be done, but it was fixed up on the quiet, so to speak, an’ folk were more or less ashamed of it, an’ if they couldn’t get a sum right they hadn’t the courage to ask anyone to help ’em.

“Now Silas P. Cornu happened to call there one day for some objects for the Tontine Museum, of which he was secretary, an’ he was sorter struck by the difficulties the inhabitants had with their figgerin’ up. He had been working at a mechanical arrangement for a long time back in his spare hours that was to do abstruse calculations with its wheels an’ cogs that no man livin’ could do with his head, even if he wanted to- lograthums they called ’em. I won’t say what a lograthum is, ‘cos I don’t know, but I reckon there’s cities been built, an’ nations riz an’ fallen, that never had a derned lograthum to divide among ’em, so they don’t seem, as you might say, absolutely essential to human progress.

“However Silas seemed to think there’d be a run on ’em if they could be turned out slick, an’ he no doubt saw dollars in it, for he put a power of time in the job. But those lograthums, sir, were tricky, an’ weren’t to be had in a hurry, an’ Silas sorter began to see as life wouldn’t be long enough to get the machine properly fixed up an’ the patent registered.

“Now when he came to Athens he saw at once that although he couldn’t get his lograthum machine in er workin’ order he could easily rig up a smaller machine on similar lines that would do all that Athens wanted, an’ bring in a fair amount of remuneration. He argued, ‘If the inhabitants of thishyer city don’t wanter soil their heads with figgers they’ve no cause to. Let ’em invest in a calculatin’ machine, an’ they can reckon on the work bein’ done for ’em aut’matic’ly.’ So he went home, an’ in a few months he had turned out an attractive lookin’ article – somethin’ between a sewin’ machine an’ a box-organ – as would do anythin’ in simple addition for twenty-five dollars. For an extra ten dollars you could add a switch which would include multiplication, an’ there Silas stuck. He couldn’t tack on division or subtraction, no matter how many dollars you’d plank down.

“Still, notwithstandin’ these limits, it was a tidy article, an’ as soon as it was on the market Athens went in for it bodily. There wasn’t a store of any size or a citizen of any standin’ but had a twenty-five dollar Calculator. Most of ’em went in for the ten dollar extra switch as well, for when you come to think of it you can’t get far, even with classical tastes, without havin’ a multiplication sum on your hands now an’ agin. How those Athens folk managed without either division or subtraction I don’t know, but I s’pose that people that air content to think about Homer, an’ Venus, an’ J. Cæsar, an’ talk in Greek an’ gum-Arabic, don’t do much in that line.

“Silas made a sight of dollars out of Athens, but he didn’t do much with it in other cities. Outside that centre of learnin’

folk weren’t too proud to do their figgerin’ up for themselves, an’ they only heaped derision on the canvasser that called offerin’ the calculatin’ machine. But in Athens Silas did well. His Calculators were so constructed that they couldn’t go wrong. Pretty well all accounts that came in were checked by it before bein’ paid, an’ no two machines were ever known to express a different opinion, either in summin’ up or in multiplyin’.

“They had other advantages as well. They could be used as foot-rests, an’ when you were not resin’ the thing for math’matical purposes you could beat eggs in it or clean knives an’ cutlery in general. He was a handy man at inventin’, was Silas Cornu, an’ he always put as much inter his notions as he could pretty well squeeze.

“Well, sir, mechanical math’matics hummed in Athens city for a considerable period. Figgers were at a discount, an’ it was a long since a leadin’ citizen had done a sum openly on his own account. Then there came a reg’lar bust up.

“James J. Jordan, mayor of the city, kept a big book-store. He had all the volumes about Homer, Venus, J. Cæsar and the rest, an’ grammar-books of all the dead an’ dyin’ languages. He practically did all the sellin’ to the University an’ the schools, an’ if anyone else wanted a book he’d be pretty well sure to go to Jordan’s for it. Some biggish accounts were run up there, an’ everybody paid ’em without a word when they bore the stamp of Silas Cornu’s Calculator.

“It had seemed to many citizens for some time past that literature, an’ indeed livin’ gen’rally, cost more’n it oughter, but they reckoned that was’ the fault of the dollar an’ not of the article. No one ever thought of doubtin’ Silas Cornu’s Calculator, for any two of ’em always agreed, an’ if machines lie they generally do it by themselves an’ not in pairs like human bein’s.

“Well one day an account was sent in to the Treasurer of the University. Now it happened he’d only just got the job, an’ bein’ new to Athens, he wasn’t above doin’ a bit of figgerin’ out of his own head. He found on that account an overcharge of fifty-two dollars. So next time he was in the city he called on Jordan an’ pointed out the mistake.

“Jordan was sorter supercilious. ‘Air you aware, sir, thishyer account was added up by Silas Cornu’s Calculator?’

“‘I don’t care who or what added it up. It’s wrong,’ said the Treasurer.

“‘Do ye mean to tell me that ye doubt the acc’racy of that machine?’

“‘I don’t say as I doubt any machine,’ said the Treasurer, ‘but I doubt this account. Add it up for yourself.’

“‘I’d scorn to do it, sir!’ said Jordan loftily. ‘Here, Bowker,’ said be to one of his helps, `just place this in the Calculator an’ ask it to be good enough to run over it again. It’s acc’racy is called inter question.’

“Bowker took the account an’ introduced it inter the slot, an’ sure enough it came out at the other side with the old amount cert’fied as bein’ correct.

“‘Ye see, sir,’ said Jordan. ‘Peraps yu’ll think twice before yow make an assertion agin which you can’t substantiate.’

“The Treasurer was kinder riled by the tone Jordan took up.

“‘D’ye think I’d take the word of an aut’matic candy box?’ – he called Silas Cornu’s invention an aut’matic candy box, sir! ‘Haven’t I got a head on my shoulders to do my own figgerin’? Do ye tell me this is correct?’ said he, pointin’ to the account.

“‘I do,’ said James J. Jordan.

“‘Then all I say is you’re an infernal liar!’ an’ bein’ six foot two, an’ broad in proportion, he left that store undamaged.

“Well, sir, he went straight to the Principal of the University an’ laid the matter before him. The Principal took up the same line of argument as Jordan, said Cornu’s invention was, like J. Cæsar’s wife, above suspicion, placed the account in his own Calculator, an’ there it came out with the same total.

“‘Add it up yourself,’ said the Treasurer.

“But the Principal couldn’t do this, as he’d taken pertic’ler care to forget his figgerin’ long ago. However he agreed to refer the matter to a neighbourin’ university, which was runnin’ strong at the time on math’matics.

“Well the account was sent there, and came back with a certificate that it was wrong by fifty-two dollars, the precise amount stated by the Treasurer.

“Well, sir, if there had been an earthquake I reckon the Principal couldn’t have been more disturbed than he was when he saw that certificate, for the foundations of pretty well everythin’ in Athens city rested on the acc’racy of Silas P. Cornu’s machines, an’ here were two of ’em not only lyin’ but actually agreein’ in their lies. Hovever, before the Calculator was publicly accused he thought it would be only fair to write to Silas an’ ask him if he could explain the matter.

“Silas came down himself in a hurry, an’ said a mistake was absolutely impossible. All Calculators had been personally tested, an’ were warranted for twenty years an’ two months. They were weather-proof, burglarproof an’ mistake-proof. You might blast ’em to bits by dynamite if you were so disposed, but if you used ’em accordin’ to his instructions they’d never lie – George Washington wasn’t in it for veracity. However, he would inspect James J. Jordan’s pertic’ler machine.

“So he called on Jordan an’ asked to see his Calculator. Jordan wasn’t for showin’ it at first, but Silas produced a revolver from his vest an’ handled it persuasively, so he was taken to the machine. Silas felt it all over an’ examined the fittin’s.

“‘Thishyer machine’s all right for calculatin’ purposes, or egg-beatin’, or knife-cleanin’. You’ve nothin’ to say agin its egg-beatin’ or knife-cleanin’, have you?’ said he, turning to the Treasurer.

“‘I have nothin’ to say agin those pertic’ler accomplishments,’ said the Treasurer. ‘All I say is it don’t add up fair.’

“‘We’ll soon see to that,’ said Silas. ‘Jest draw out an invoice, Jordan, for that row of books.’

“Jordan, lookin’ more or less foolish, sat down and penned it out. Silas put it in the slot an’ turned the crank, an’ out it came at the other side added up and cert’fied.

“‘Now, is thishyer correct?’ said Silas, handin’ it to the Treasurer.

“The Treasurer sits down an’ works it out. ‘Thirty-three dollars overcharged,’ said he.

“‘Give it me,’ said Silas,’ sittin’ down to figger it up himself.

“I wasn’t there at the time, but I have been told that Silas looked mortal bad when he found the Treasurer was correct. That account was wrong by thirty-three dollars.

“Silas was a man of action. He pulled out a pertic’ler tool from his pocket, an’ in two minutes had the Calculator open an’ was peerin’ inter it.

“‘What’s thishyer, Jordan?’ said he, black as thunder.

“‘What’s what?’ said James J. Jordan, lookin’ pertic’ler white.

“‘What’s this ile mean?’ asked Silas sharply.

“‘We has to ile ’em occasionally, to keep ’em in order,’ said Jordan.

“‘Air you aware,’ said Silas, ‘that the full title of this machine is ‘Cornu’s Patent Dry Calculator?’ an’ he pointed to the letterin’.

“‘Yes, I’ve noticed that.’

“‘Why did you apply m’isture in the shape of ile? I spec’ you know what “dry” means.’

“‘I thought it referred to the character of the calculatin’ work the machine did. Most folk call figgerin’ up pretty dry.’

“‘Have you read the instructions sent with each machine,’ continued Silas.

“‘Can’t say as I’ve seen any instructions. Have you Bowker?’ said Jordan to his help.

“Bowker shook his head. Apparently neither of them had seen those pertic’ler instructions.

“‘Thishyer machine was in perfect order for calculatin’ acc’rately,’ said Silas to the Treasurer, ‘so long as my instructions were followed. It’s a dry machine, an’ I laid pertic’ler stress on that in my instructions, an’ I cautioned the owner agin employin’ ile or any other m’isture. If you go opposite to my instructions I’ll not be responsible for the calculatin’ done. It’s a pity, Jordan, you forgot those instructions,’ he went on slowly, an’ sorter fidgetin’ with his han’s. ‘P’raps you’ll remember this a bit better,’ an’ with those words he flashed out his six-shooter an’ fired straight at him.

“He was a smart man, that Treasurer, at other things as well as figgers, for he knocked the barrel up before Silas pulled the trigger. There was a big globe of the world standin’ on a shelf just above Jordan’s head. The bullet went in at Australia an’ came out of the Atlantic at the other side.

“Silas glanced reproachfully at the Treasurer, an’ then seein’ that Jordan an’ his help had vanished, pocketed the revolver.

“‘Let’s inspec’ some other machines,’ he said gloomily.

“They called on twenty-five stores runnin’, an’ found twenty-five Calculators with their insides swimmin’ in ile. Word got round that Silas was comin’, an’ the proprietors of those stores were not at home. Seemed as if they’d all been called away sudden.

“On further investigation there wasn’t a single Calculator in the place that was correct in its figgers. It turned out that the peculiarity of the machine for figgerin’ ahead when ile was applied had been ascertained pretty early on by Jordan an’ his frien’s, an’ on a given day all the store Calculators were iled, an’ a young man was sent round to the private residences to inspec’ the machines there free of cost an’ see that they was in workin’ order.

Apparently, he put them so, for they always agreed with the store reckonings. Out of three hundred an’ forty Calculators in Athens pity, three hundred and thirty-nine were iled up to the chin, an’ the other one, evidently kep’ for egperimentin’ purposes, had jest been lubricated with vaseline. The power of that machine for summin’ up in favour of the seller was remarkable. No doubt there’d have been a big run on vaseline at Athens if that Treasurer hadn’t turned up.

“That did for Silas P. Cornu’s Patent Dry

Calculator as far as Athens was concerned, an’ folks began to understand how it was their incomes had done so little for ‘ern since Silas’s invention was sprung. They were sorry for Silas, for somehow all his inventions jest stopped short of complete success. No one blamed him that his machine wouldn’t stand ile, but in future, save for egg-beatin’ or knife-cleanin’, they dare not use it themselves or buy at a store that employed its services.

“James J. Jordan an’ thirty-nine other storekeepers were soon afterwards sentenced to three years’ imprisonment an’ a heavy fine for incitin’ Calculators to perjure themselves, an’ aidin’ an’ abettin’ ’em in the act. A young machine iler narrowly escaped conviction also.

“Athens University was obliged to take up figgerin’ agin after this disclosure. They hired a top-sawyer professor from the neighbourin’ university to put ’em in the way of it an’ start ’em fair. They knocked off an hour or two a day from Homer, an’ Venus, an’ J. Cæsar, an’ devoted ’em to addin’ up an’ multiplyin’, an’ now it ‘ud take James J. Jordan all his time to get a red cent more for a volume than he oughter hive.

“Silas went back to Tontine, an’ soon after resigned his situation at the museum so as to devote himself altogether to his lograthum machine. He hoped that Athens University would take it up when it was ready. Maybe Athens University would, but that pertic’ler machine never was ready.”

Hering would write several more stories that were sufficiently science-fictional to be included in the ISFDB. Of interest here is “Mr. Broadbent’s Information” which appeared in Pearson’s Magazine, March 1909, and has been anthologized in the last decade.

Baxter, as all the world knows, has created life artificially, and he is now developing the process. I remember his speech at the last Academy dinner, when he responded for Science. “What I aim at producing,” he said, “is an automaton endowed with strong vitality, great muscular strength, and a rudimentary brain, an automaton capable of doing the work of an unskilled laborer or artisan. I will anticipate the criticism that such a production will have a profound influence on the labor market by stating that I shall never rest content until I have placed it within reach of the pocket of every working man, who will then have a mechanism in his house capable of doing his work for him at a minimum of cost, and enabling its owner to walk into the country, take part in his favorite sport, or spend his time in the public library — whichever course he may deem to be the best for advancing his immortal destiny. That is how I intend to employ my discovery for the benefit of the human race.”

Baxter is of course a base villain. His creations are not quite what he claims. Poor mankind never gets to benefit.

On a lighter note, and apropos to nothing at all, the issue of Cassell’s with Hering’s story also had a page of jokes. If you want to know how far back some jokes go – and how little the world has changed – here’s a brief sampling.

BARBER (insinuatingly): You hair wants cutting the worst way, sir.

SOURBY (in the chair): That’s the way you cut it last time.A man likes a woman who shows him that she is clever.

Oh no; a man likes a woman who shows him that he is clever.DORA: Jack, who was that lady with your father? I didn’t know you had a sister.

JACK: Oh, that one isn’t a sister. That’s father’s step-wife!

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was The Diamond Service Brigade His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is finally available wherever books can be ordered over the internet. Visit his companion site RobotsinAmericanPopularCulture.com for much more on robots.

I will admit to an early morning lazy read, but what is a ‘dry calculator’? I don’t associate ’wet’ with calculators unless it needs oil. Or does it only count fish?

When you wake up take a closer read of the story. You’ll realize that “ile” means “oil,” exactly what dry calculators *don’t* need.