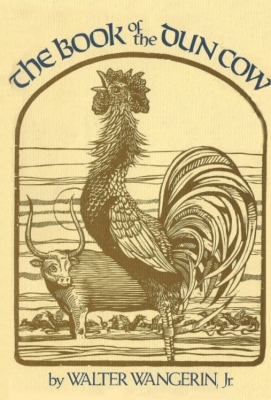

The Golden Age of Science Fiction: The Book of the Dun Cow, by Walter Wangerin, Jr.

|

|

|

The National Book Awards were established in 1936 by the American Booksellers Association. Although the Awards were not given out between 1942 and 1949 because of World War II and its aftermath, the awards were reestablished in 1950 and given out annually since then. Since 1950, only US authors are eligible for the award, which is designed to celebrate the best of American literature, expand its audience, and enhance the value of good writing in America. From 1980 through 1983, the American Book Awards were announced as a variation of the National Book Awards, run by the Academy of the American Book Awards. While the National Book Awards were selected by a jury of writers, the TABA program relied on entry fees, committees, and voters made up of groups of publishers, booksellers, librarians, and authors and critics. The change was controversial and a group of authors including Nelson Algren, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Roth, and Susan Sontag, among others, called for a boycott of the award. The American Book Award included genre categories, presenting awards for mysteries, science fiction, and westerns. Two awards were presented in the science fiction category, one for hardcover, one for paperback. The genre awards were abandoned after a single year. The only winner of the National Book Award for Paperback Science Fiction was Walter Wangerin, Jr.’s The Book of the Dun Cow, which had originally been published in hardcover in 1978 and reprinted in paperback in 1979. The Awards were presented in New York on May 1, 1980 at a ceremony hosted by William F. Buckley and John Chancellor. Isaac Asimov presented the science fiction awards.

The Book of the Dun Cow is an allegorical novel which is based, in part, on Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale” from The Canterbury Tales, which itself is based on the earlier stories about Reynard the Fox. Wangerin’s novel also falls into the same category as George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Richard Adams’s Watership Down, and Brian Jacques’s Redwall series, being completely populated by animals.

The story mostly follows Chauntecleer, a rooster who not only rules over the henhouse and the farmyard, but the surrounding countryside. As Wangerin originally portrays the rooster, he is an arrogant ruler, unyielding in his actions and intent on preserving his prerogatives. As the novel progresses, however, Wangerin begins to show other sides of the rooster, indicating that he does take an interest in those who are his subjects. When the Ebenezer Rat is accused by the community, rather than base his judgement on the rat’s previous actions or his own personal feelings, Chauntecleer actually considers the accusations and the evidence. Wangerin’s more complete picture of Chauntecleer is of a ruler who takes his responsibilities, as well as the perquisites that come with them, very seriously.

In contrast to Chauntecleer, Wangerin also writes of Senex, a rooster who rules a roost far to the north. Old and senile, Senex laments the lack of a rooster to take over after him and listens to the voice of Wyrm, an evil Midgard serpent-like living beneath the surface of the earth. The result is an evil offspring, a mixture of rooster and Wyrm, Cockatrice. While Chauntecleer is an arrogant, but ultimately benevolent ruler, and Senex is an ancient ruler simply trying to stay relevant, Cockatrice is a tyrant whose goal is to destroy all those around him. Eventually Cockatrice’s army of basilisks attacks the yard ruled over by Chauntecleer.

Every aspect of The Book of the Dun Cow demonstrates the story’s medieval antecedents. Although Chauntecleer isn’t a modern leader, he does epitomize the way a good monarch was viewed during the period and his subjects’ reaction to him demonstrates that he is acting in ways they expect. Cockatrice is a tyrant, partly by nature, but also because his line has been swayed by Wyrm, a stand-in for a denial of a Christian God, or more aptly, perhaps, the acceptance of Lucifer. The Wild Turkeys who are Chauntecleer’s subjects are shown as rejecting the Word of God, which limits what Chauntecleer can do to protect them. Everything, of course, culminates in the battle between the forces of good and evil, but in a much more medieval sense than is seen in much of modern fantasy literature.

Given the strong religious themes of the novel, it isn’t entirely a surprise that Wangerin holds a Master of Divinity and has served as a pastor. He published a sequel to The Book of the Dun Cow in 1985 entitled The Book of Sorrows, which picks up immediately after the first book ends. In 2013, Wangerin published a third volume in the series, The Third Book of the Dun Cow: Peace at the Last.

Other nominees in the paperback category included Samuel R. Delany’s Tales of Nevèrÿon, Vonda N. McIntyre’s Dreamsnake, Norman Spinrad’s The Star-Spangled Future, and John Varley’s The Persistance of Vision.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I loved this book, the one and only time I read it. I wonder how it would stand up now? Weirdly enough, there is a collection of Irish myths compiled by some Irish monks back in the middle ages, which goes by the same name – so called because the cover was supposedly made from cow hide.