Against the Darkmaster Kickstarts for High Fantasy Gamers of the World

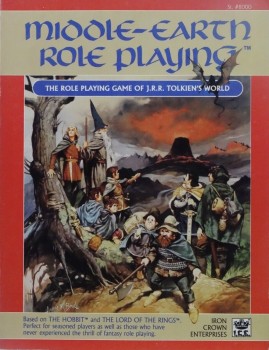

Sword & Sorcery is a late attraction for me. My first and abiding love, ever since encountering Tolkien in the fifth grade, was and has been Epic High Fantasy, with its Heroes struggling against the Dark Lord in a battle of unequivocal Good versus Evil. I have said it before, and I think this present context makes it appropriate to say it again: when this thing called “fantasy roleplaying” first came to my attention, having no older siblings or neighborkids to introduce me to the more popular and recognizable Dungeons & Dragons, I spent my allowance at Waldenbooks on the red box set of Middle-Earth Role Playing (MERP).

I was young, roleplaying was brand new to my friends and me, so, of course, we didn’t “play it right,” just as, as an adult, I learned that those other kids who were playing D&D at the same time weren’t running their games “correctly,” either. MERP is derived from the Rolemaster (RM) percentile system, which was first designed as modular additions to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (1e), and has a reputation for complexity and lethality. I add this second characterization because RM’s critical hit tables might be its most famous feature. My young friends and I enjoyed many idle sessions simply reading descriptions out of the charts, language that evinced wry and gory humor in the spirit of 1980s slasher films. Here’s a favorite example: “Blast annihilates entire skeleton. Reduced to a gelatinous pulp. Try a spatula.”

When the designers of the forthcoming Against the Darkmaster (VsD) revisited this favorite childhood game of theirs, they, too, felt the desire to “play it wrong.” After awhile, they realized they had made so many tweaks and modifications to the core rules that they, essentially, had created a game of their own, a houseruled or hacked “retroclone” of MERP, reformulated to emulate specifically the works of Tolkien and his imitators, fantasy movies of the 1980s, and epic heavy metal music.

I was an early adopter of the VsD playtest, and a not infrequent critic of the VsD rules system. You can find the first in a series of these critiques here on The Rolemaster Blog. The designers aim to distinguish their game from others such as D&D through its emphasis on its source materials. In VsD, player characters are heroes, not “mere” adventurers of the Sword & Sorcery variety. The “plot” of a VsD campaign is intended to contain a high stakes struggle between Good (the PCs) and Evil (a force culminating in the person of the Darkmaster, played by the GM).

The QuickStart is available for Pay What You Want over at DriveThru RPG, so you don’t have to listen to what I have to say about the rules! But if you do want to hear me out, I go into even greater depth over at The Rolemaster Blog already cited (though I’m reviewing, there, an earlier version of the QuickStart currently available on DriveThru). Here I’ll give a brief overview, with notable observations.

VsD is a d100 system, and it’s derived from Rolemaster. What this means is that nearly every task resolution requires a d100 roll + character stat bonus + any skill to succeed at a set target number difficulty after applying any extraneous modifiers (usually, for unqualified success, you want to break 100). Combat is slightly different: attack rolls are applied to attack tables, wherein the total value is cross-referenced with the opponent’s armor type. If the strike is a success, the opponent loses hit points (which heal quickly—they’re more like “exhaustion points” in this game) and, sometimes, takes a critical hit. In this latter case a d100 is rolled again, and a (usually gory) wound description is read aloud.

In their recent interview, the designers said that this is why combat should be avoided—it very often results in instant death or dismemberment (though the PCs, in this game, possess a “metacurrency” called Drive Points that can be spent to mitigate some of these effects). The designers believe that the lethal nature of this combat emulates their source fictions, in which the heroes most commonly are running from or avoiding adversaries rather than confronting them.

Spell casting is similar to combat: the higher the roll, the better the effect, and additional Magic Points can be spent while powering certain spells to accomplish greater and more spectacular applications. It is possible for nearly every type of character class to have access to spell casting abilities—and that is another aspect of the game, inherited from Rolemaster: characters develop in the way that their players want, by assigning skill points at each level advancement. The “class” merely predicates what comes most easily for the character.

If this system stands out from others in appreciable ways, I argue that it’s in its character background options. MERP had a few tables on which players could roll; charts that yielded special abilities, magic items and stat increases were the most popular. VsD’s menu provides features that are tied directly to character narrative. Together the Gamemaster and players use these—and the PC’s Passions, another narrative mechanic in the game — to construct the inception of a saga that should be as exciting as any epic fantasy trilogy.

I recommend VsD, firstly, for anybody who ever has been curious about Rolemaster or MERP (looking at you, John O’Neill) but has, until now, been intimidated by its reputation of crunch and complexity. VsD is a streamlined and elegant d100 system within this family of games. I also recommend it to veteran RM gamers seeking something a little more pick-up-and-play. Yet neither of these recommendations are to suggest that VsD is not complex: I ran the VsD playtest for almost a year before my home group returned to our home brewed version of Swords & Wizardry (which is Original Dungeons & Dragons), but our home rules now reflect our experience with VsD. So this is saying that the game design inherent in VsD has much to offer for any fantasy roleplaying gamer, especially those seeking to emulate heroic fantasy roleplaying in the manner of The Hero’s Journey, Beyond the Wall, and World of Aetaltis.

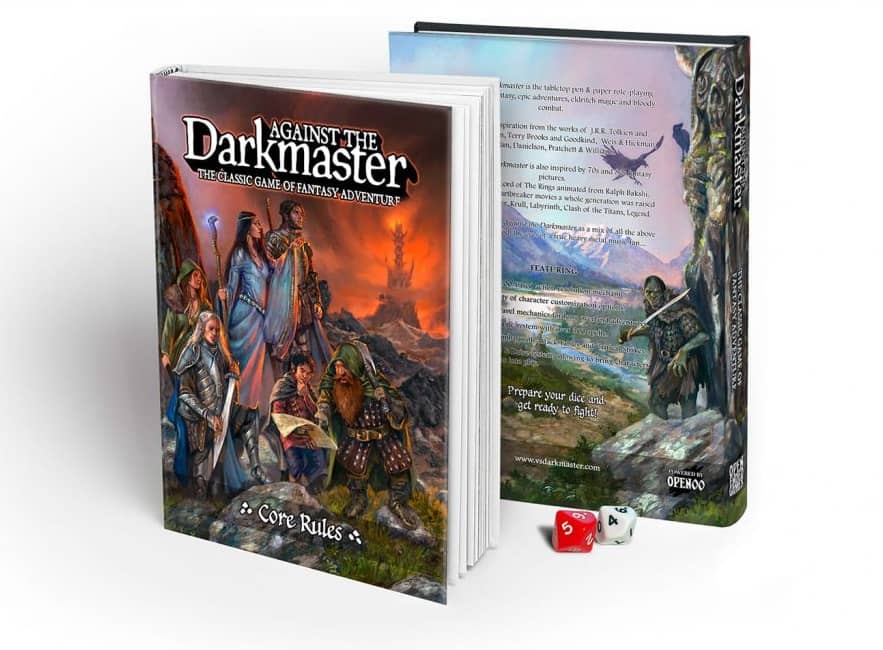

And if that pitch doesn’t sell you, then just look at the art! Look at that cover (top), by Andrea Piparo! In the back half (left), we see minions of the Darkmaster, an infestation in an idyllic, unpolluted land, creeping up on the heroes, in the front cover (right), who are preparing to pierce directly into the source of the contagion itself, the realm of the Darkmaster. This tells you exactly how the game should be played! Who even needs rules with such beautiful art? And (I almost need not say) any fan of the “original” MERP (1e) will recognize a direct homage to Angus McBride’s cover for that work.

And if that pitch doesn’t sell you, then just look at the art! Look at that cover (top), by Andrea Piparo! In the back half (left), we see minions of the Darkmaster, an infestation in an idyllic, unpolluted land, creeping up on the heroes, in the front cover (right), who are preparing to pierce directly into the source of the contagion itself, the realm of the Darkmaster. This tells you exactly how the game should be played! Who even needs rules with such beautiful art? And (I almost need not say) any fan of the “original” MERP (1e) will recognize a direct homage to Angus McBride’s cover for that work.

When I was young, I played MERP in many ways, many times, until finally setting it aside—lovingly torn and tattered, spilling pages out of its weakening binding patched with masking tape—for other games. MERP has been frequently criticized as a poor emulation of Tolkien’s work precisely because it is derived from D&D, and I’m wondering if we kids, while “playing it wrong,” unconsciously brought it more into conformance with Tolkien’s vision of Good vs. Evil. Those game sessions are lost in nostalgia and fading memory, but I wonder if our young, blundering experiences are reflected in any way by the impulse of the designers of the forthcoming VsD in making a childhood favorite perform more decisively according to the themes and tones of everything we loved about the 80s.

Please back the Kickstarter for Against the Darkmaster.

Gabe Dybing has been a small magazine editor (Mooreeffoc Magazine 2000-2001), often a writer, and usually a gamer. He is most interested in the “northern” fantasy tradition and frequently examines intersections between that topic and gaming. For Black Gate he has contributed many articles, including pieces on Poul Anderson, J.R.R. Tolkien, and roleplaying games.