Gyro Gearloose’s Little Helper

I started reading comics in about 1958, or at least those are the oldest ones I still have, mostly bedraggled, torn, or coverless from hundreds of readings. They were age-appropriate Disney comics, from Dell Comics. (Gold Key wouldn’t take over until the 1960s.) I was indiscriminate, of course, having no idea which were good or even what good meant, so I had piles of Mickey Mouse and Chip ‘n’ Dale. I soon realized why I was drawn to those titles. They were all regular features in the flagship Walt Disney Comics and Stories (WDCS), the comic of comics. A Donald Duck tale always ranked first, better told than any of the others. Those stories contained witty adventures, taking place all around the world, and often off it in that post-Sputnik year. Oddly, no Donald Duck comic could be found. Instead, I picked up a comic about a non-title character: Uncle Scrooge. The miserly multiplujillionnaire drove all the adventures, roping in Donald, and his nephews, and the other residents of Duckburg, a city more amazing and more fully realized than Metropolis in the Superman comics I soon found. That superiority was due entirely to writer/artist Carl Barks but I wouldn’t know that for decades. No matter. The difference between a Barks story and anyone else’s was a lesson I took with me to better comics and then to better science fiction. There was fun and there was good and then there was superior. Thus a critic (none dare say carper) was born.

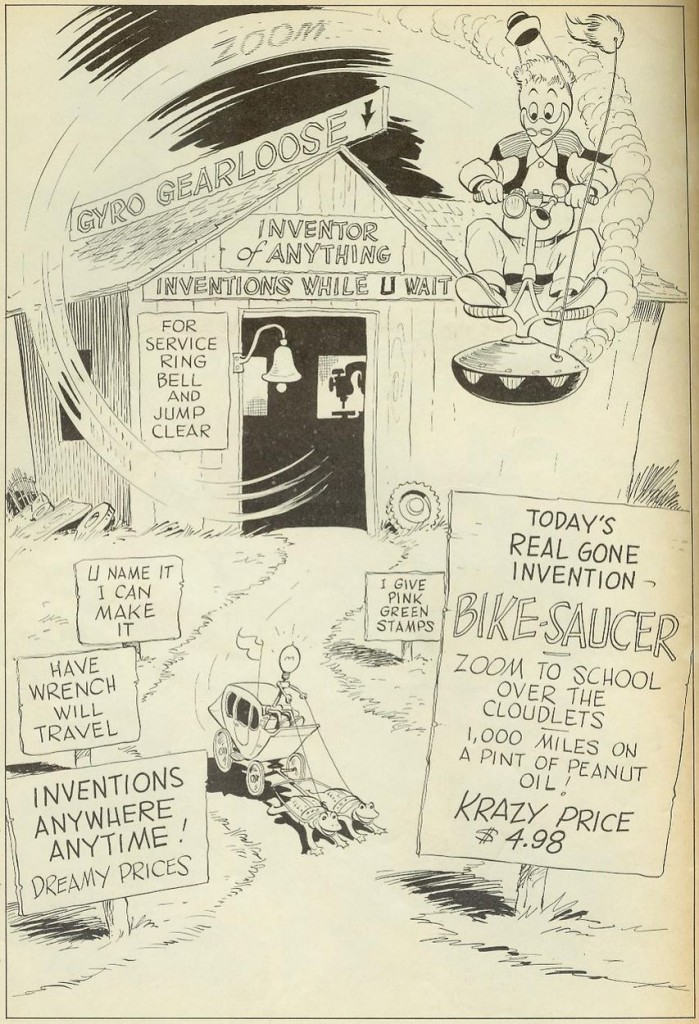

Uncle Scrooge appeared only quarterly, so it was a rare treat to be savored. Two stories filled an issue, a long Uncle Scrooge tale and a short backup about Gyro Gearloose (also written and drawn by Barks I later found out, although only a kid could not realize that the two had to be done by the same superior hand). Gyro Gearloose! What a fantastic, perfect name. Gyro (not a duck but a large chicken; don’t ask) was an inventor, the best inventor of all time. His inventions always worked, always, every single time.

Their only problem was ID10T error. The inventions were perfect, the operator not so much. Unintended consequences ran riot in every story. I loved Gyro Gearloose. And I especially loved his robot.

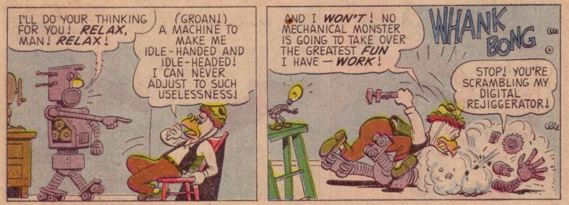

|

|

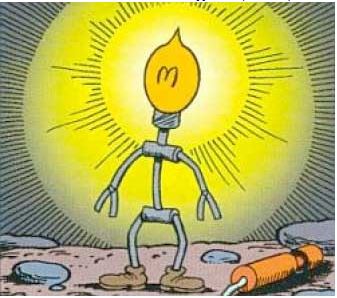

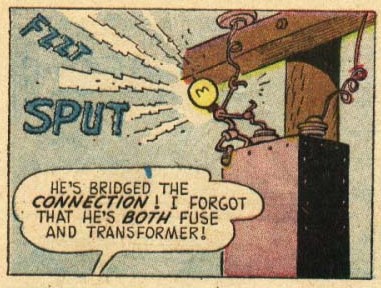

Gyro’s robot is a stick figure of a robot, a kid’s drawing made sophisticated by movement and expression 30 years before John Lassiter animated Luxo Jr. Bars for shoulders and hips and spine, wires for arms and legs, a light bulb for a head. (In time, the bulb would light up whenever it has an idea. Obvious in hindsight, but not to the creator. Let that be a note for everyone trying to read purpose into an author’s every word.) Its appearance occasionally varied: the claws would turn into Mickey Mouse-like white-gloved hands, but with merely three-fingers. I thought the bars might represent resistors but, much later, we’d learn that it was “both fuse and transformer.” Apparently, Gyro invented miniaturized circuits long before Noyce.

Nameless and wordless, the figure first appeared in the back-up story “The Cat Box” in Uncle Scrooge #15 (Sept.-Nov. 1956). Basically a doodle, a bit of background to fill in the empty space inevitable in a panel, a reward for those who read and reread the stories, the figure would blossom from a humble beginning.

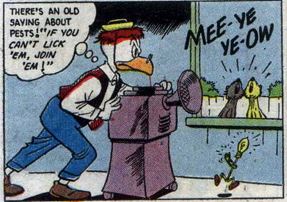

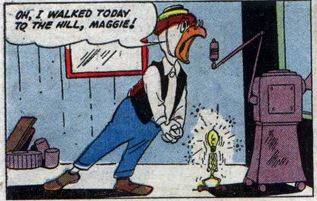

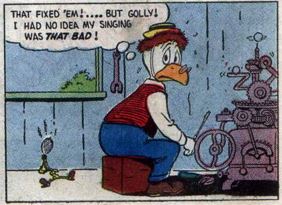

“The Cat Box” (Gyro stories then did not have titles, but they are found today in Barks databases) is a bit of a dud as a story. Gyro, his concentration scrambled by cats’ yowling, invents a machine to translate their sounds into English. (He calls them “human words,” a rare people intrusion into the hermetic Duck universe.) He learns that they are, wait for it, hep cats. [rimshot] To retaliate, he reverses the polarity on his machine to turn his singing into cat. That not only drives the cats away but scrambles his unfortunate companion.

|

|

|

Even in that first appearance, we can instantly see that the figure exhibits a full range of what, following Barks, we can call human emotions. There can be no doubt of what it’s feeling, and suffering.

Barks was trained as an animator, whose first thought when creating a character was to poke at it, goose it into motion, and see what hijinks it was capable of. The next story, “Fishing Mystery” in Uncle Scrooge #16 (Dec. 1957-Feb. 1958), shows the robot not merely trailing Gyro around, but imitating his actions and reactions, sometimes ahead of him, unblinded by Gyro’s dreamy certainty (or doubt) of what was supposed to happen.

|

|

|

The tiny figure, like those singers in the terrific documentary 20 Feet From Stardom, was a major talent in its own right. Like so much else in Disney comic history, the name was applied retroactively, because fans and followers needed a tag to put on the character. They had little to go on. At first, Barks seldom had Gyro even directly notice his shadow, much less address it. But even Barks occasionally nodded. There is an instance of Gyro calling it “Helper.” And Helper morphed into Little Helper, which is the best term to search on. (It’s Little Bulb in the Duck Tales cartoons.) Helper is canonical, because helper is how Barks thought of his creation, as quoted in Tom Andrae, Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book: Unmasking the Myth of Modernity.

I created his helper because much of the time I had Gyro working all alone on some goofy machine. I put the little guy in to fill up the corners of the panels. I treated him as a complete nobody; not even Gyro noticed he was around.”

That changed. “The Cat Box” was only Barks’ third Gyro story. The more Gyro stories Barks drew, the larger the role for Little Helper. In a few years it would blossom into a star, recognized by everyone. Nor would he be the only robot Gyro encountered. In the Barks years, that is. Some Gyro stories cannot be definitively attributed to any writer. I’ll reference them if Barks is listed as artist at the obsessional I.N.D.U.C.K.S. site. Stories neither written nor drawn by Barks may be fun but have no place here. As far as I know, this is the first listing of Barks’ Gyro robot stories.

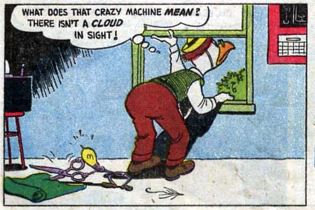

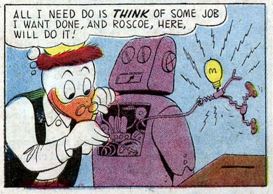

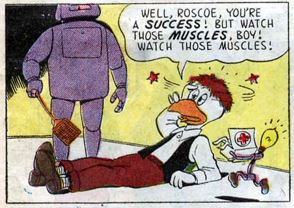

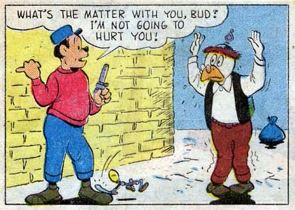

Barks didn’t wait long to introduce a full-sized robot. “Roscoe the Robot” appeared in Uncle Scrooge #20 (Dec. 1958-Feb. 1959). Gyro invents a thought-controlled robot to do his chores. Interestingly, Barks immediately gave it a name, Roscoe. (Pondering why a one-shot contraption got a name while the permanent Little Helper didn’t would make a good academic paper.) Untended consequences? Hoo-boy. Asked to swat a pesky fly, Roscoe does, no matter that it has landed on Gyro’s head. Confident in Roscoe’s strength, Gyro takes him (him? yes, man’s name = him in robotland) along as a bodyguard until they are confronted by a voice. Roscoe, terrified, takes off. Little Helper, in a tiny aside that would go unnoticed on first reading, takes action. Roscoe was reading Gyro’s thoughts and doing what he wanted to do. The fault in robots is not in our stars, but in ourselves.

|

|

|

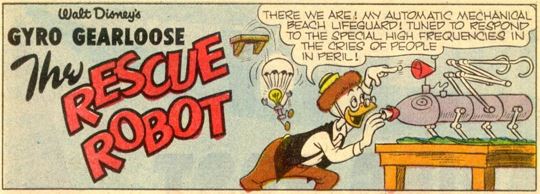

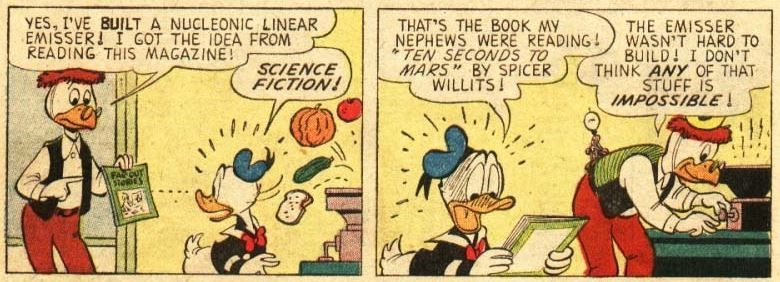

“The Rescue Robot” in WDCS #251 (Aug. 1961) is another of Gyro’s altruistic plans to help people. Again, untended consequences is the entirety of the plot. Built to save drowning people at the beach when they call for help, the robot responds with equal alacrity to the screams and cries for help that blanket the world’s noisiest beach. When it (non-anthropomorphic in appearance, it does not rate a name: them’s the rules) rushes into a house where a woman has screamed because of a scary tv show, it’s Little Helper who pulls its plug. Note that Gyro now refers to Helper as his helper, lower-case, though.

|

|

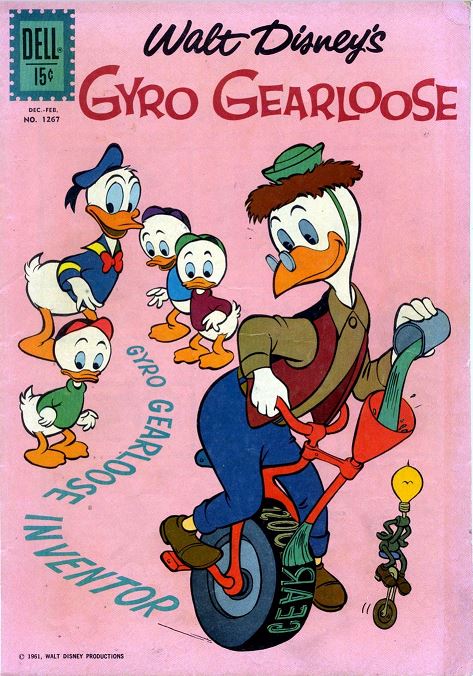

Sadly, Gyro never got his own comic book. Not that Disney didn’t give him a chance. In 1959, 1960, and 1961 they gave him four issues of his own in the comic book that simultaneously had the most issues and is the least known. Disney, remember, did not publish their own comic books. They contracted with Western Printing and Lithographing Company, an octopus of a firm that had tentacles wherever print could be found. Western published the Little Golden Books and the Big Little Books and the Dell Comics. Dell Comics started with a series of one-shots called Four Color Comics in 1939, which restarted with new numbering in 1942. After one hundred issues, the comic stopped calling itself Four Color and instead named the issue after the single character it featured, even though the numbering continued.

By mid-1959, Four Color, invisibly to all but comic historians and insiders, had zoomed past the 1000 mark, with more than 50 additional titles appearing by the end of the year. Dell was not synonymous with Disney; it contracted with everybody. They did issues for Warner Brothers (Elmer Fudd and Beep Beep, the Roadrunner), Hanna-Barbara (Quick Draw McGraw and Ruff and Reddy), newspaper comic strips (Steve Canyon and Nancy and Sluggo), television shows (Fury, Lawman, and Sea Hunt), movies (The Big Circus), and movie shorts (The Three Stooges and Spanky & Alfalfa, The Little Rascals), just in the twenty issues before the first Gyro Gearloose. How they expected any potential readers to find a specific title in this flurry of promotion is beyond me. For better or worse, Gyro was the lead and sole character in #1047 (Nov. 1959-Feb. 1960), #1095 (April-June 1960), #1184 (May-July 1961) and #1267 (Dec. 1961-Feb. 1962), twenty stories plus one-pagers, more than five years’ worth of Uncle Scrooge back-ups. It was impossible to do that many Gyro tales without sticking in a robot somewhere.

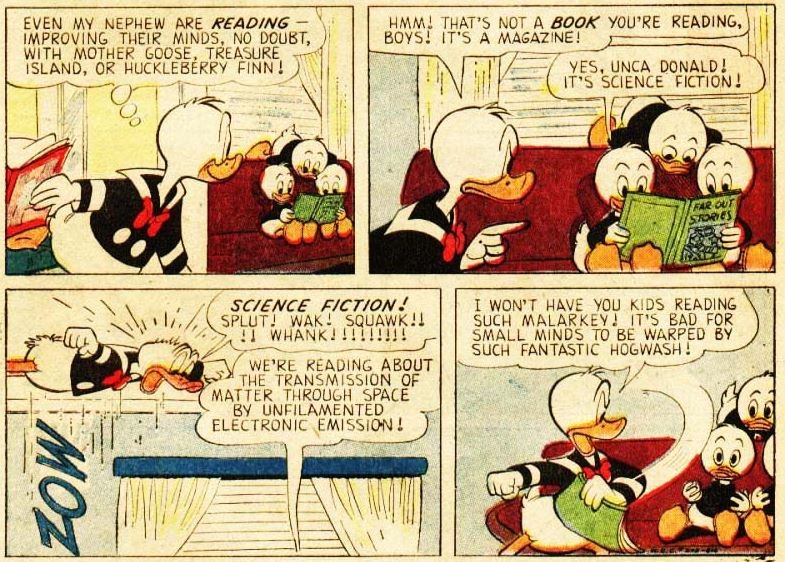

Whether he meant to, whether he even thought he was doing so, Barks wrote many science fiction adventures. “The Twenty-four Carat Moon” from Uncle Scrooge #24 (Dec 1958) is one of the best sf stories I’ve ever read. I mean that. It has adventure, characterization, a twist ending, and a moral. Barks’ views on science fiction were admiring, at least if we believe these scenes from “Stranger Than Fiction,” WDCS #249 (June 1961), the first from page 1 and the second two pages later.

|

|

(“Spicer Willits” is too weird a concoction not to be a hidden reference. My guess is that the name is a takeoff on Bill Spicer. Barks toiled in anonymity despite his huge fan base. Some fans looked at Western Printing’s name in the indicia and sent fan letters that got discarded. Spicer somehow tracked Barks’ name and address down and sent the first fan letter that reached him. He never forgot.)

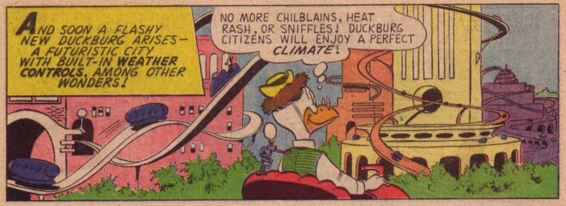

I’d argue that there’s little that’s more pure science fiction in the public’s mind than a vision of a futuristic city, a technological utopia full of all the signifiers of the future I cover in my Flying Cars and Food Pills website. Flying cars, sure; robots doing all the work, of course; safety devices everywhere, at last; weather control under a dome, sleep learning, high speed monorails, yes, yes, yes. If that’s true, then the ultimate Gyro sf story was “Monsterville,” Four Color #1184.

“Monsterville” is one of the strangest stories Disney released at the time, maybe ever. For one thing, nobody is sure who wrote it. Nobody ever signed anything in the Disney universe, maintaining the fiction that all this goodness sprang directly from the mind of Walt. And the provenance of many older comic scripts is in doubt. None of that matters for most of Barks work. The fan scholars have through monumental efforts traced down the artist and writer of virtually every Disney publication, with Barks fanatics the most devoted. Four Color #1184 is an anomaly, seemingly the only issue to feature a major Barks-created character whose authorship is mostly unknown. Vic Lockman is known to have written one of the five stories, though, and most connoisseurs prefer to give him credit, or discredit, for “Monsterville.” Barks undoubtedly did the art, nevertheless, and an argument can be made for his writing the story as well.

“Monsterville” begins with a routine gag that Barks had used previously. Gyro is out for a spin in his hovercar when he is stopped by a cop, accused of speeding. It just looks fast – Gyro doesn’t break laws – so the cop gives him a ticket for flying too low. Gyro broods. Not only is Duckberg not ready for new technology, but the current technology is unlivable. Gyro plots out a complete personal vision of a technological utopia and convinces the Duckberg city government to build it.

When Walt Disney died, he was laying out plans for his last big project, completing a half-hour video meant to persuade Florida government officials to allow him to build a “planned environment demonstrating to the world what American communities can accomplish through proper control of planning and design.”

That was in 1966, five years after “Monsterville” was written. I’ve read many books about Disney, a fascinating collection of obsessions himself, and searched others online and I’ve never seen a mention of “Monsterville.” It could be mere coincidence; creating the city of the future was a common dream of the era and the urban renewal movement was busily tearing down vast swatches of most major cities. That’s most likely, given that the story eviscerates Walt’s fantasy of the future.

Gyro loves the clear, safe, efficient new city. None of the other residents are as happy, though. Firemen are useless when hoses put out fires automatically and police are secondary to crime traps. Gyro has deprived them of what made their lives meaningful, even fun.

Fun itself is no longer fun. Huey, Dewey, and Louie’s toys play without assistance and Donald takes 23-hour naps after his 10-minute shift at the automatic factory.

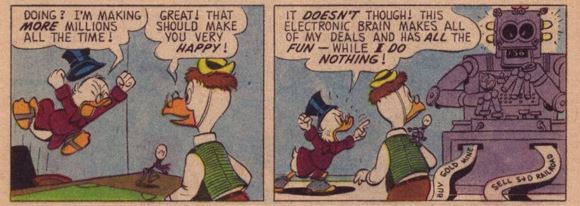

Gyro begins to harbor doubts. Another invention is necessary. He goes back to his workshop for the ultimate shock.

Yes, Little Helper is putting Gyro out of business with a robot of his own. And Gyro snaps.

Like every other robotic or computerized system in fiction, the entirety of Duckburg’s automatic processes can be turned off with one switch. Gyro pulls the switch and forces the city back from its future. He promises not to meddle in their lives henceforth. True to himself, he cheats, without breaking any rules. A flying rocket car! Note Little Helper as the jubilant hood ornament.

Did Barks write “Monsterville?” Comics pundits consider it poorly written and beneath him. Yet the story is nothing but a giant set of unintended consequences, Barks’ specialty. More pertinently, in life, and his work, he was an ardent environmentalist who preferred the pastoral past over progress and the mess it often left behind. Most importantly, the entire story is suffused with the ethos that one’s work is one’s fun, fulfillment, and meaning. Barks unquestionably believed that. But maybe Vic Lockman also thought that way. Heck, I do. It’s as much a mystery as whether Walt read this and thought, “I’ll show him. I’ll do it right!”

I’ve saved the ultimate Little Helper story for last. For a change, Gyro doesn’t invent a robot in “Duckburg’s Day of Peril,” Uncle Scrooge #36 (Sept.-Nov. 1961), but he has to battle one nonetheless. A movie company is shooting in Duckburg and they’ve built Goliath, the Giant from Outer Space, a remote-controlled robot. Debris from Goliath’s house-smashing wrecks the control panel so the panicked movie-makers seize upon Gyro and beg him to help. Even he can’t whip up an anti-robot ray in a few seconds, so when he sees the director trapped in a house Goliath is advancing on, Gyro rushes in to save him. Too late. Goliath lifts the house in the air. “Gyro’s helper,” now officially recognized as such in a caption, saves the day, making like David with his slingshot aimed at a vital bulb. The savior of Duckburg gets a medal bigger than his head. Unnoticed? Not anymore. Little Helper has reached his peak.

|

|

|

It’s not Barks; it’s not even American. Brazilian artist Jorge Kato did this cover for Zé Carioca (Feb. 1967). I just can’t think of a better image to close this out on.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was That Buck Rogers Stuff His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is finally available wherever books can be ordered over the internet. Visit his companion site RobotsinAmericanPopularCulture.com for much more on robots.

As I think about it, it occurs to me that my relationship with Carl Barks is a lot like my relationship with Ray Harryhausen — when I was young, I’d encounter their work (screenings of Sinbad movies; reprinted Barks stories in Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories) and not know anything about the creator, but recognize that what I was seeing was head & shoulders better than most of the other, similar stuff that was out there.

Now I’m very happy that I know more about both of them, and about the remarkable work they produced.

Carl Barks stayed with me from the time I was nine or ten till now when I’m in my sixties.

By the way, his body is buried in the same Grants Pass, Oregon, cemetery where my dad’s parents’ bodies were laid to rest.

The site is Hillcrest Memorial Park in Grants Pass. The Barks grave is in Lot 2, Section 31, of the Rosewood part of the cemetery.

Barks had lived at 810 NE Oregon Avenue in Grants Pass. It isn’t a fancy-looking house, but its has a pleasing mountainous location:

https://www.instantstreetview.com/@42.445075,-123.304619,277.03h,-3.65p,1z

Sorry — “stayed with me” could be ambiguous. I didn’t know Barks, never met him. I meant that his work has stayed with me.

Dale Nelson

Here is Barks’ obituary, from the Grants Pass Daily Courier 29 August 2000:

Carl Barks, 99, of Grants Pass died Friday, Aug. 25, 2000, at his home.

Funeral services will be at 3 p.m. Thursday at Lundberg’s L.B. Hall Funeral Home, with Bob Wood, pastor of Redwood Christian Church, officiating.

Memorial contributions may be made to Lovejoy Hospice, 400 N.E. E St., Grants Pass, OR 97526.

Barks was born March 27, 1901, in Merrill. He started working as a cartoonist with Walt Disney Studios in 1935. He retired from Disney in 1966 and continued to write Duck Tales until 1973. He came to Grants Pass from Temecula, Calif., in 1983.

During his years at Disney, Barks worked as a storyboard artist and writer. He wrote and illustrated almost 500 Donald Duck comic books between 1942 and 1966. He is known as one of the Disney legends.

He took pride in his story writing. He also did oil paintings at his home.

Survivors include a daughter, Dorothy Gibson of Bremerton, Wash.; four grandchildren, six great-grandchildren and eight great-great-grandchildren. A daughter, Peggy, died before him.

http://web.thedailycourier.com/obituaries/search.html?id=10051

Dale Nelson

I loved he Gearloose stories! Thanks much for this article.

[…] TAKING THE TUBE. Steve Carper has a fascinating profile of “Gyro Gearloose’s Little Helper” at Black […]