Fantasia 2019: Final Thoughts

Yesterday I posted my last full review of a film from the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival. Today, then, a post looking back at this year’s Fantasia. First, as always, my profound thanks to everyone who puts the festival together. And thanks as well to the audiences, who give the festival a reason for being. Special thanks to everyone I watched movies with, everyone I waited in line with, and everyone who I talked with and hung out with during Fantasia 2019.

Yesterday I posted my last full review of a film from the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival. Today, then, a post looking back at this year’s Fantasia. First, as always, my profound thanks to everyone who puts the festival together. And thanks as well to the audiences, who give the festival a reason for being. Special thanks to everyone I watched movies with, everyone I waited in line with, and everyone who I talked with and hung out with during Fantasia 2019.

This year was a bit odd for me, in that for the first week or even two I felt that while I was watching a lot of very solid feature films I was nevertheless missing a certain sense of surprise; a feeling I normally have at Fantasia of being blindsided by a movie, or a set of movies one after another. This may have simply been a function of what films I happened to see, or a subjective impression caused by some minor health issue (chronic fatigue takes many forms). Certainly that sense of mild shock did set in before too long. But it came from an unexpected place. What struck me as most impressive about the festival this year were not features but the short films.

It has been observed that the relation of short film to long film is more-or-less that of the short prose story to the novel. The short format is capable of powerful work, condensing narrative into terse, elliptical, allusive flashes. Artists often work at that length before embarking on longer stories, sometimes to hone their craft, sometimes to build a name, sometimes because they love the form. But audiences tend to prefer immersion in a longer story. In any case, while there are a number of outlets for prose short stories, short film rarely gets the same kind of exposure.

There are exceptions. It’s perfectly fair to talk about TV episodes as short film, for example. But one of the strengths of a good short is the way it can build a world very quickly, establishing as much as we need to know about character and telling a story with them in just a few minutes. So I want to write for a moment about a film I saw this year that I haven’t yet covered: “Balloon,” by Shin Hyun-woo.

Every year Fantasia has several blocks of animated shorts for children that play at the McCord Museum of Canadian History, not far from the main Fantasia theatres. I have two young nieces, and saw two blocks of those films this year. Plans for coverage here from age-appropriate reviewers fell through, but I have to say as an adult viewer that I was generally impressed by the craft I saw in these shorts.

All good things must come to an end, they say, and for me Fantasia 2019 ended at the Hall Theatre with the Korean action-horror movie The Divine Fury (사자, romanised as Saja, literally Emissary). Directed by Kim Joo-hwan, it follows Yong-hu (Park Seo-jun), a champion MMA fighter who lost his father under mysterious circumstances at a young age. In the present, when mysterious wounds appear on his hands and he is attacked by a demonic force, a blind shaman guides him to exorcist Father Ahn (Ahn Sung-ki), who tells him the wounds are stigmata and give him great power in fighting demons. The two team up, reluctantly on the part of Yong-hu, who holds a grudge against Christianity after the death of his father. But there are dark forces at work in Seoul, and Yong-hu must use all his skills to defeat the forces of hell on earth.

All good things must come to an end, they say, and for me Fantasia 2019 ended at the Hall Theatre with the Korean action-horror movie The Divine Fury (사자, romanised as Saja, literally Emissary). Directed by Kim Joo-hwan, it follows Yong-hu (Park Seo-jun), a champion MMA fighter who lost his father under mysterious circumstances at a young age. In the present, when mysterious wounds appear on his hands and he is attacked by a demonic force, a blind shaman guides him to exorcist Father Ahn (Ahn Sung-ki), who tells him the wounds are stigmata and give him great power in fighting demons. The two team up, reluctantly on the part of Yong-hu, who holds a grudge against Christianity after the death of his father. But there are dark forces at work in Seoul, and Yong-hu must use all his skills to defeat the forces of hell on earth.

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up.

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up.

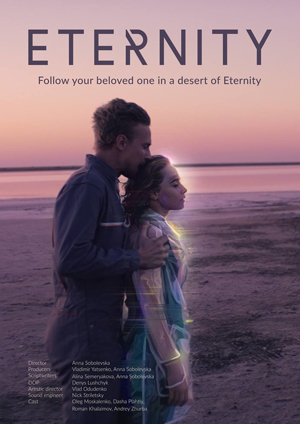

After taking a day to attend to various non-cinema matters, I came early to the last day of the Fantasia Film Festival. I had two movies I wanted to see in theatres, but first I wanted to catch up on something I’d missed when played on the big screen: the 2019 International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase. Luckily, I was able to watch it at the Fantasia screening room. Uncharacteristically, American shorts dominated this year; in an appropriately science-fictional statistic, 7 of 9 movies were from the US, with one from Australia that ended the showcase (at least in the order described in the Fantasia program) and one from Ukraine that began it.

After taking a day to attend to various non-cinema matters, I came early to the last day of the Fantasia Film Festival. I had two movies I wanted to see in theatres, but first I wanted to catch up on something I’d missed when played on the big screen: the 2019 International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase. Luckily, I was able to watch it at the Fantasia screening room. Uncharacteristically, American shorts dominated this year; in an appropriately science-fictional statistic, 7 of 9 movies were from the US, with one from Australia that ended the showcase (at least in the order described in the Fantasia program) and one from Ukraine that began it.