That Buck Rogers Stuff

|

|

Those of us on the inside, the fans steeped in the history of science fiction and fantasy, mark the beginning of modern science fiction with Hugo Gernsback’s launching of Amazing Stories in August 1926. A thousand historians, critics, and commentators use that date as a dividing line between the proto-fictions of Verne and Wells and the lesser-known William Wallace Cook and George England and the Frank Reade Jr. series of boy’s adventures and Gernsback’s own favorite, Clement Fezandié.

The outside world didn’t see it that way. They didn’t see Amazing Stories at all or its first competitor, Astounding Stories of Super-Science, or the various Wonder magazines Gernsback started in 1929 when he lost control of Amazing. They were invisible, no matter how we today look back at Doc Smith or Murray Leinster or Edmond Hamilton. Or a first story by Philip Francis Nowlan, “Armageddon—2419 A.D.,” a fairly silly and racist Yellow Peril yarn starring one Anthony Rogers, or a sequel, “The Airlords of Han,” in which Nowlan tries to excuse the racism by postulating that the evil Han were not Chinese but alien interlopers who “mated forcibly with the Tibetans.” Disintegrator rays and anti-gravity flying belts and an “electrono plant operating from atomic energy” impinged not a bit on the public consciousness.

Yet by 1935, that “Buck Rogers stuff” was a national catchphrase, in high culture and low. Malcolm W. Bingay criticized Sir Arthur Eddington’s book, New Pathways in Science, as “Buck Rogers stuff panoplied in jargon that passes for scientific terminology.” And talking about new children’s toys, an article reported that “the Buck Rogers stuff backs ‘em all off the sales map, nearly tying Mickey Mouse, who had a head start.”

What happened? Not science fiction pulp mags, still stuck on those same three titles that had been around since the twenties, but a daily newspaper comic strip, Buck Rogers—In the Year 2429, that started on January 9, 1929. John Flint Dille, who happened to own a comics syndicate, had an idea for a futuristic strip. He chanced upon that August Amazing and for impossible-to-guess reasons saw something in Nowlan’s story. (How would history have been changed if he chose Doc Smith’s first Skylark of Space story, running in that same issue, instead?) Dille paired Nowlan’s writing with art from Richard “Dick” Calkins, overcoming his protestations that he really wanted to draw a strip about cavemen. Changing the title date to an exact 500 years in the future proved to be magic. Newspapers took notice. In February, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette ran a contest asking readers for thoughts on “What Do You See 500 Years Ahead?” Entrants were obviously adults, and the winners included such inspired guesses as “The English Channel tunnels are not being used and will be abandoned”; “Sahara produces half of the world’s food. Artificial rain has made a productive country out of a desert”; and “Stored light has eliminated darkness in most places.”

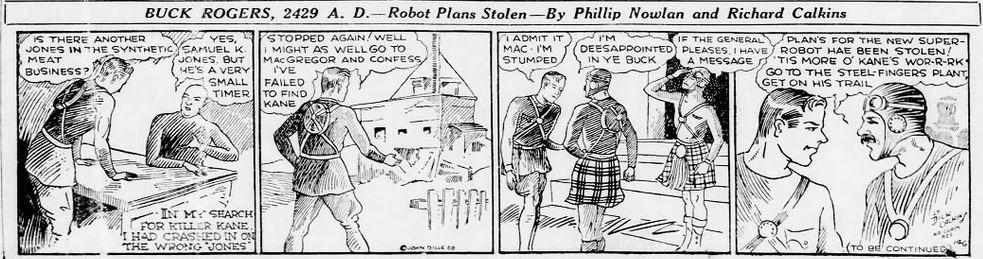

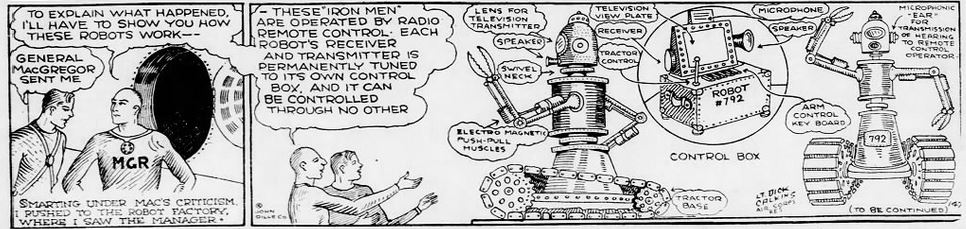

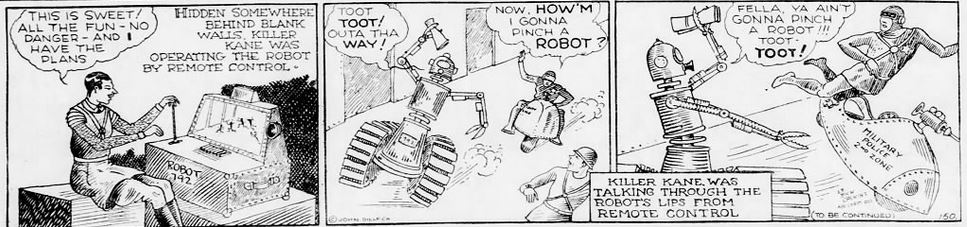

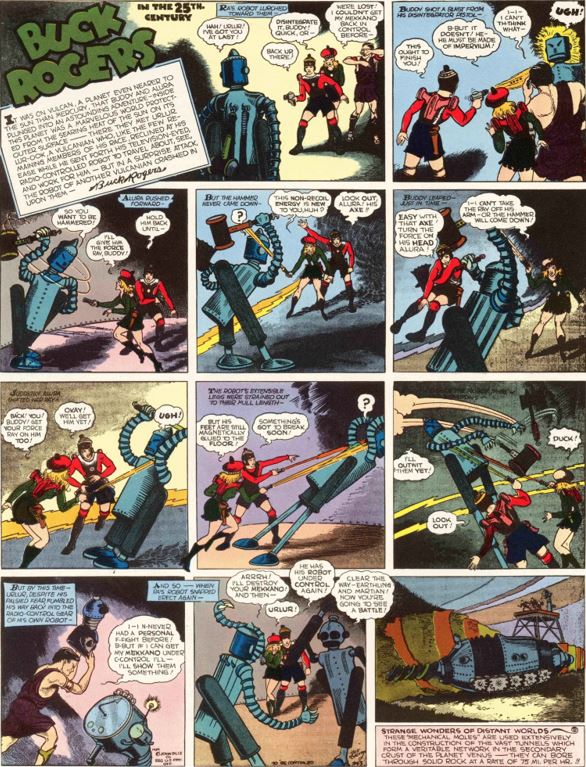

Robots quickly joined the marvels of the world of the future. The last week in July saw a sequence in which arch-enemy Killer Kane steals the remote control device for a new super-robot and, with his typical wiliness, uses the controller to have the robot break into the safe containing its own plans. “Electro magnetic push- pull muscles” gave its arms all the strength a villain could hope for.

|

|

|

|

|

Oh yeah, cats and kitties, how can you resist dialog like, “Fella, you ain’t gonna pinch a robot??? Toot-Toot!” Yowsah! (All emphasis and punctuation in quotes as in original.)

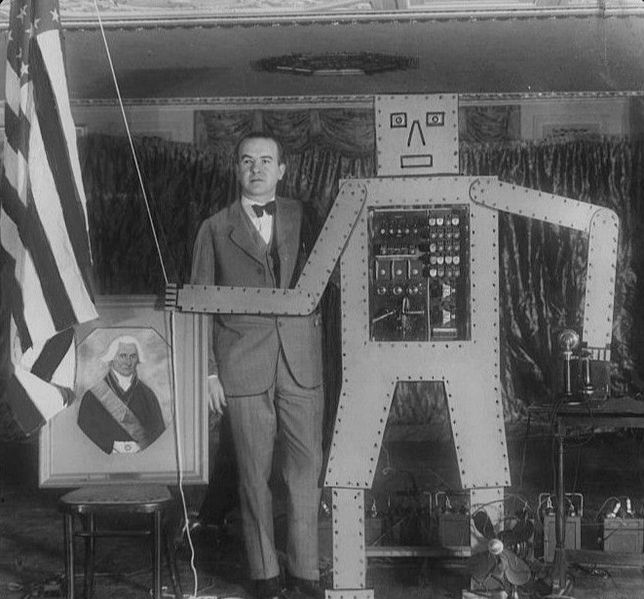

Another sequence later that year showed that Nowlan paid attention to robots in the news. The Westinghouse corporation was a pioneer in remotely controlling devices by sending sound signals down telephone wires. They sent inventor Roy Wensley and his creation out on a publicity tour in 1927, after Wensley got the bright idea to use cardboard to surround the control boxes into an outline of a cartoon robot he called Televox.

Televox was briefly the national name and image of a robot. Nowlan referenced Televox as a generic name for robot on December 7, 1929.

Note that Buck is still fighting the evil Han. A month later, Buck’s girlfriend, the future girl-warrior Wilma, gets kidnapped by The Tiger Men of Mars, and the strip zooms off into space, seldom looking back, and forever associating spaceships and alien planets with science fiction and zap guns, robots, and the rest of Buck’s paraphernalia. Far more importantly, 1930 brought the first Sunday strip. Daily newspaper strips were a solid base, basically cash cows that could run more or less unchanged for decades. The big money, prestige, and attention devolved from the full-page Sunday color strips, housed in a separate section of the newspaper. Only one paper in a city could run a strip, so a popular strip was crucial to circulation and the subject of enormous advertising and the occasional print war.

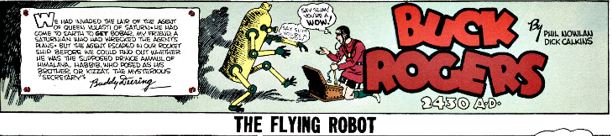

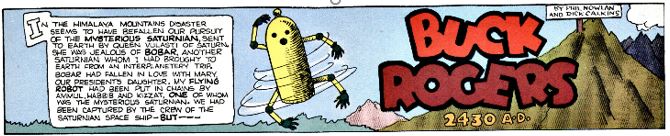

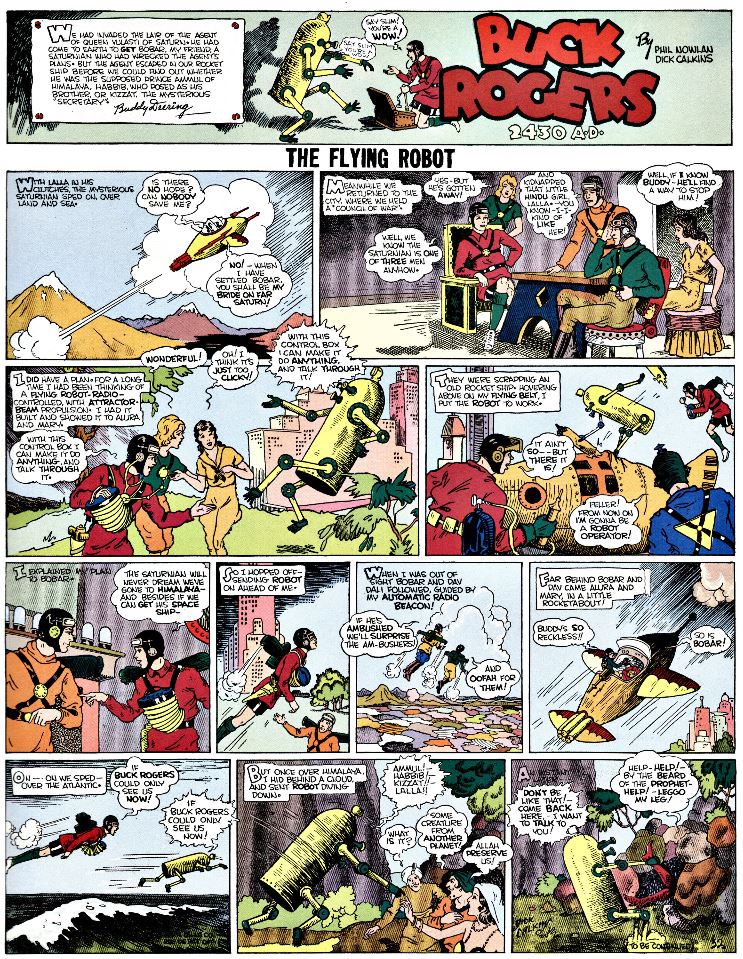

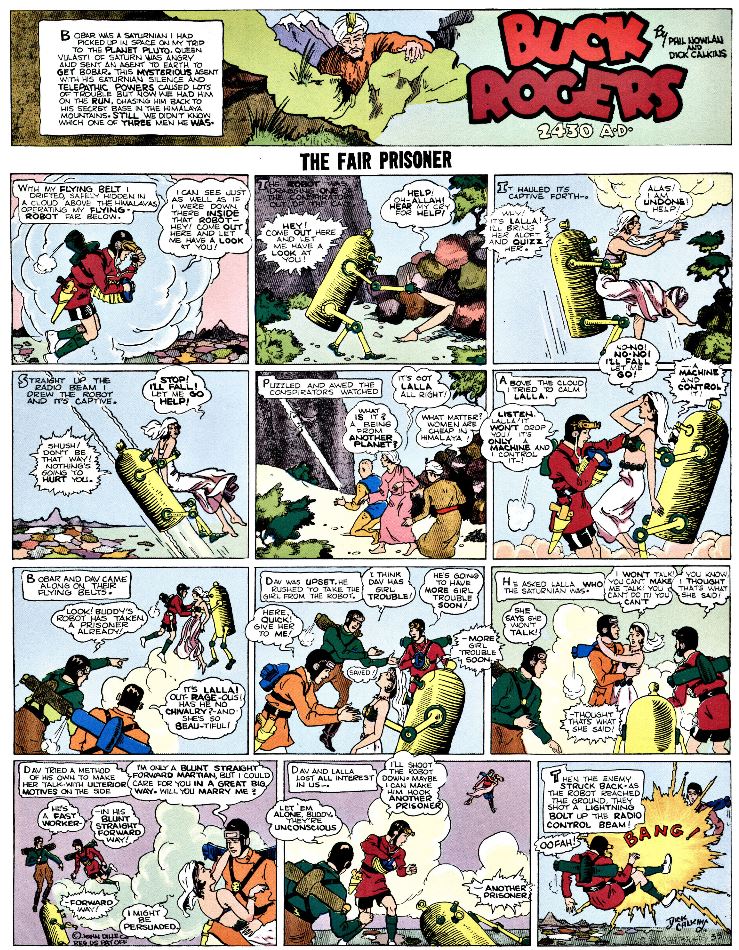

Buck Rogers 2430 A.D. debuted in March, still signed Phil Nowlan and Dick Calkins, but the changes were many. Calkins felt that a seven-day schedule was too much so Dille brought in Russell “Buster” Keaton as a ghost. Far more oddly, Buck Rogers no longer appeared in his own strip. Dille thought that having two separate adventure continuities, one Monday-Saturday, the other Sunday to Sunday, would be confusing to readers. Instead of Buck and Wilma, therefore, the Sunday strip starred Buddy and Alura. Buddy was Wilma’s brother; Alura was a princess of Mars who happened to look like exactly a human – specifically, exactly like Wilma. I’d think that calling doppelgängers by different names would be far more confusing than separate continuities, hardly a new idea in 1930, but I don’t have a merchandising empire and Dille did.

Robots suddenly appear in the middle of a sequence called The Mysterious Saturnian on November 11, 1930. In the Saturnian storyline, Buddy and his gang have been battling an evildoer from Saturn when a Hindu lass named Lalla is kidnapped and stashed in the Saturnians’ secret Himalayan lair. Buddy snaps into action, pulling out of nowhere a “flying robot. Radiocontrolled with attractor-beam propulsion.” Buddy explains that “with this control box I can make it do anything and talk through it.” “Oh! I think it’s just too clicky,” slangs Mary, the president’s daughter. The robot flies in and grabs Lalla, who believes that she’s merely being kidnapped again by a different alien.

|

|

Keaton’s anatomical ineptitude is embarrassingly proven by the image of the robot lifting Lalla by her breasts. He got dumped for Rick Yager, whose astronomical scenes were far superior.

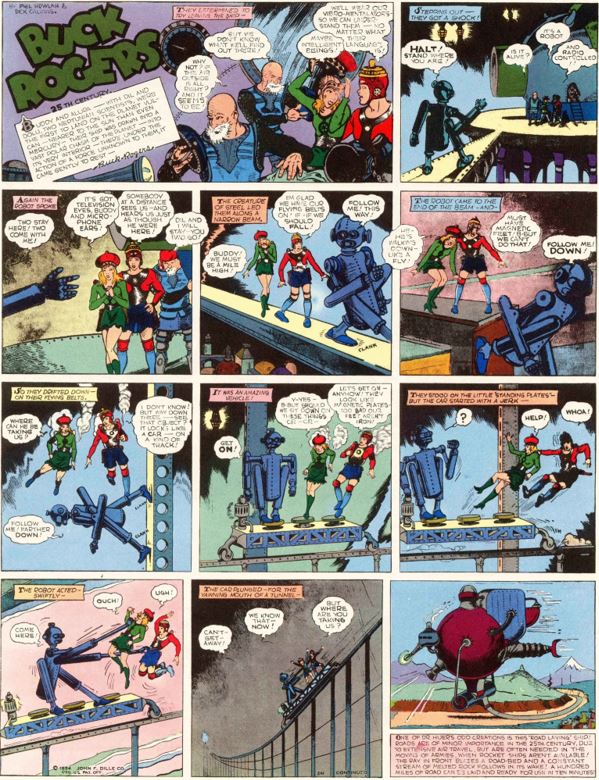

Robots reappeared in “Mekkanos of Planet Vulcan,” which started on October 24, 1934. Breaking out of the fourth dimension that fall Sunday, Buddy and Alura find themselves about to crash into Vulcan, a once- theorized planet even closer to the Sun than Mercury. Fortuitously, their ship gets pulled into a gigantic abyss at Vulcan’s north pole and lands safely at the planet’s center, which is improbably but necessarily cool, well lit, and a source of breathable air. (Shades of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ recently published Pellucidar series.) The adventurers are greeted by a radio-controlled robot with “television eyes” and “microphone ears” (much like those of the super-robot), which leads them up, down, and across a buried city. The few remaining Vulcanians hide inside their luxurious homes in fear of their fellows, doing all business and communication through their robots’ eyes and ears.

Does this sound familiar? I mentioned William Wallace Cook earlier, whose first foray into science fiction, A Round Trip to the Year 2000; Or, A Flight Through Time, depicts a future society who battle for supremacy with thought-controlled robots. The agoraphobic and sybaritic Vulcanians anticipate the Solarians in Isaac Asimov’s 1957 novel, The Naked Sun, who have retreated from active life in favor of a world run by robots. Both Nowlan and Asimov were young men fascinated by science fiction yarns, making the connection provokingly plausible.

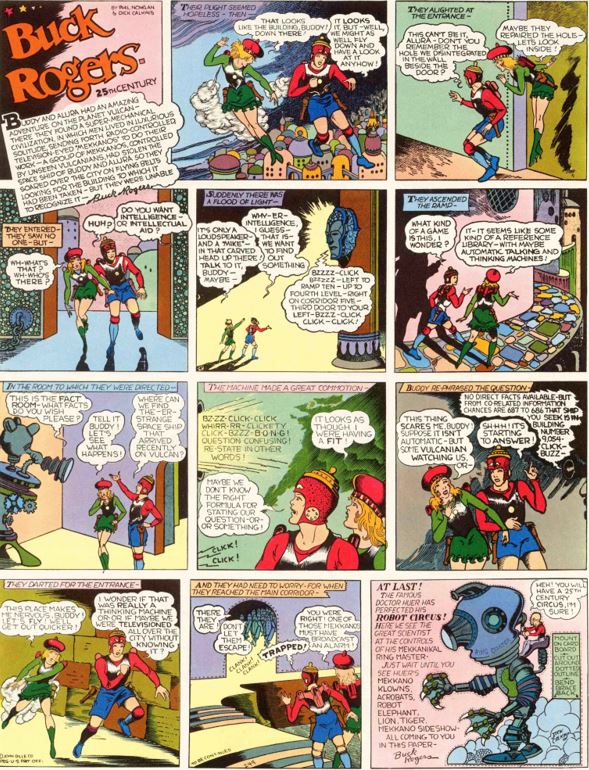

The sequence ends with one of the most prescient extrapolations in science fictional history. Lost in the gigantic city, pursued by an army of Mekkanos, Buddy and Alura enter a “fact room,” “a kind of reference library” with “automatic talking and thinking machines,” that gives them directions back to their ship.

|

|

|

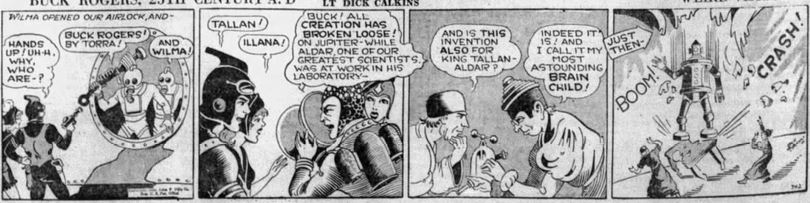

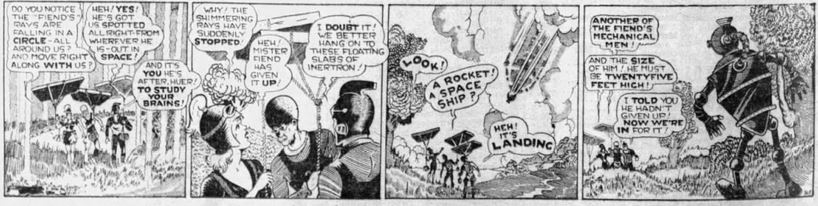

If confusion between sequences meant anything, then 1938 must have blown minds. Nowlan ran two simultaneous sequences featuring robots, “The Fiend of Space” in the daily papers and “Secret City of Mechanical Men” on Sundays.

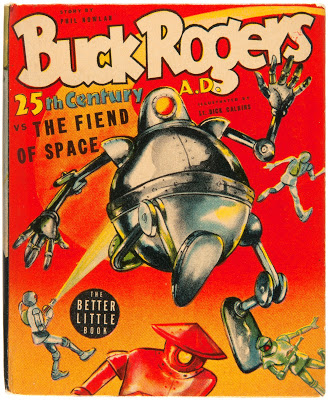

The unspeakable, ineffable, and undrawable Fiend of Space – a alien villain so horrible that the mere sight of its visage drove people insane – powered a Buck Rogers Better Little Book (the fatter version of the Big Little Book series).

So powerful was the Fiend that it did the impossible: broke through the invisible barriers between continuities and showed up in the Secret City sequence, where it teamed up with Killer Kane. First came giant automatons big enough to crack a spaceship over their knees:

|

|

< |

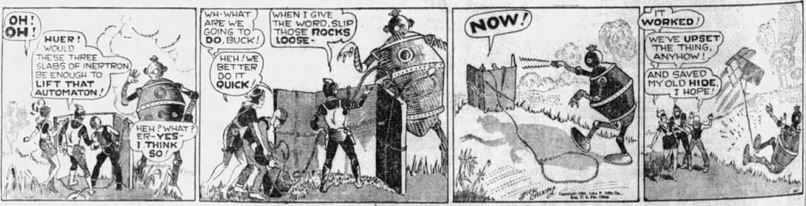

But plucky Buck has a few brains of his own:

|

|

|

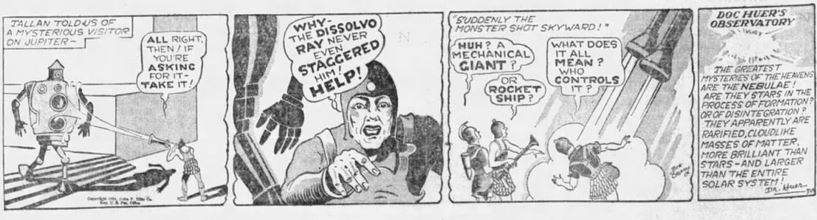

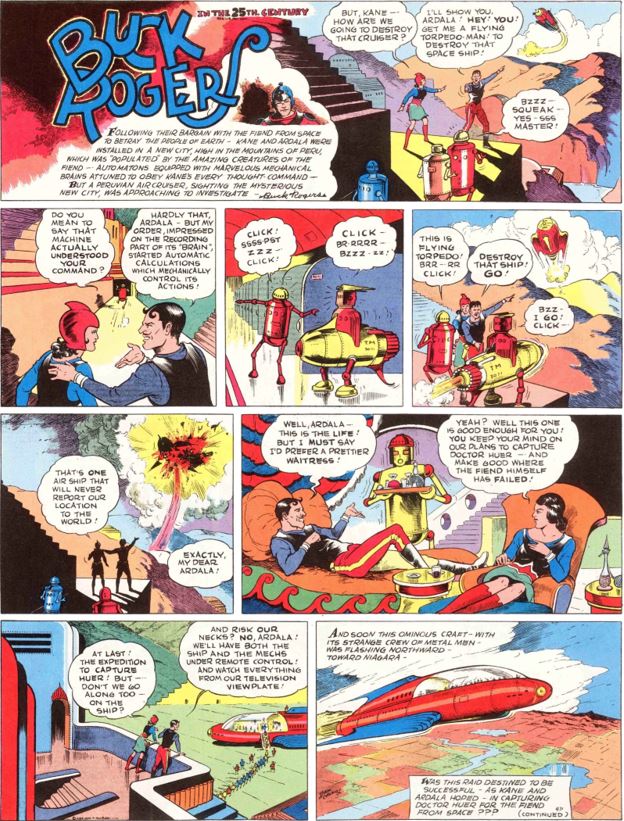

Meanwhile, Killer Kane and his moll Ardala are plucked out of space by the fiend and sent to Earth to a city of mechanical men.

|

|

|

A squadron of robot bombs would soon move out of the comic pages and onto front pages, when the German Vergeltungswaffen weapons were in fact called robot bombs.

Science fiction suddenly entered a phase of respectability after rockets and atomic weapons became all-too-real death dealers. Buck Rogers never regained his status as the premiere exemplar of future imagery. The term camp hadn’t yet been invented, but poor Buck – and his many imitators – were now camp. Literally so. Susan Sontag’s canonical list in her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” includes Flash Gordon comic strips. That Buck Rogers stuff no longer symbolically epitomized the future, but the past future, a hopelessly banal and jejune vision of progress made instantly obsolete by the slightest touch of reality. Science fiction was now for adults.

Yeah, I know. Irony is more impregnable than giant robots.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Superworld Comics His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is finally available wherever books can be ordered over the internet. Visit his companion site RobotsinAmericanPopularCulture.com for much more on robots.

![1929-12-07 Fremont [OH] News-Messenger 8 Buck Rogers televox](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/1929-12-07-Fremont-OH-News-Messenger-8-Buck-Rogers-televox.jpg)

I’ve never seen anyone else refer to Wells’s fiction as “proto-sf” much less “proto-fiction”…even if the most common term for his now most-famous work before 1929 was “scientific romance”. And 1929 is a key year, since the first competitors to AMAZING STORIES, which Gernsback founded (along with an annual companion), were produced by Gernsback, who had just lost the publishing company that published AMAZING, and so established a new one, one which published, beginning in 1929 and shortly after SCIENCE WONDER STORIES, AIR WONDER STORIES, SCIENTIFIC DETECTIVE MONTHLY and WONDER STORIES QUARTERLY, which used the term “science fiction” rather than “scientifiction” as AMAZING had. ASTOUNDING STORIES OF SUPER SCIENCE rolled in the next year, 1930, from the Clayton pulp-magazine chain.

Proto-SF is such a standard term that it has its own entry in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. See the page at: http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/proto_sf. The distinction is important to me because science fiction as a genre becomes separate from stories of scientific romance after Amazing — and Buck Rogers. Wells and Verne were writes of status equal to any others. Writers of genre sf were not. This is critical to any cultural understanding of sf.

Steve, it’s not “proto-sf” when it was laying the groundwork for current sf…and was being presented in issues of AMAZING as sf.

I’m not sure what you hope to be saying when you say writers of magazine sf, which is what I think you mean, were not the equals of any writers anywhere…the minor ones who wrote for the pulps might be looked down upon, but so were Verne and Wells, depending on whom you asked. Verne was an adventure and light fiction writer…Wells was a pop historian and seen as rather more sophisticated in the general run of things, but still not taken as seriously as a number of his peers. The sf writers of the teens and ’20s weren’t magically transformed by being included in the new sf magazines…though the first wave of pulp and Gernsbackian technologist writers who began writing regularly for the sf magazines were often not as good as prose construction as the likes of Verne or Wells…at least not at first, as in Jack Williamson’s case, but sometimes they were, as with Will F. Jenkins aka Murray Leinster. And some, like Jenkins, wrote widely for other markets ans were considered on at least the same level of sophistication as Verne, maybe a bit ahead. Usually, when the SFE and others refer to proto-sf, they are more in the realm of riding flocks of birds to the Moon, or UTOPIA or GULLIVER’S TRAVELS, not THE TIME MACHINE, much less Wells’s later work, which are sf. (And some of the later popular sf published outside the magazines, such as some of Philip Wylie’s, and Ayn Rand’s ANTHEM, is atrociously written and often called out as being such…Wylie did better and worse.)

In any case, please do fix the error, if you get a chance, that has AMAZING’s first competitor being ASTOUNDING rather than the WONDER twins and their stablemates. And thanks showing us some of these early strips.

I use proto-sf for pre-Gernsback stories because it is a useful term for me as a cultural historian. My contention is that science fiction was looked at completely differently when it became a pulp genre. My reading of contemporary commentary underlies my assertion that Wells and Verne were considered to be writers of a higher order than the pulp writers. So, for that matter, was Wylie, who never published in a sf genre pulp. I concede that Science Wonder Stories preceded Astounding by a few months, but it was so much a continuation of Amazing, just as Sloane’s Amazing was, that Astounding is realistically the first competitor. Not a single name in Bates’ first issue, not even the ubiquitous Murray Leinster, had been published in Gernsback’s Amazing. Astounding was something new from the beginning.

[…] Info on Comic Strip:https://www.blackgate.com/2019/09/25/that-buck-rogers-stuff/https://cyberneticzoo.com/teleoperators/1929-robot-792-mobile-remote-robot-philip-francis-nowlan-dick-calkins-american/ […]