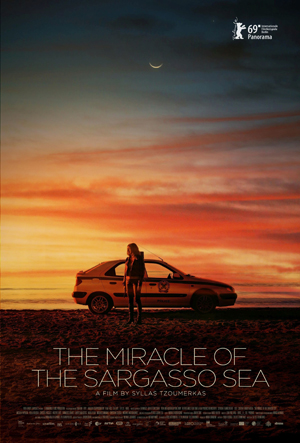

Fantasia 2019, Day 22, Part 2: The Miracle of the Sargasso Sea

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up.

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up.

The film I had at the De Sève Cinema was The Miracle of the Sargasso Sea (To thávma tis thálassas ton Sargassón, Το Θαύμα της Θάλασσας των Σαργασσών). Directed by Syllas Tzoumerkas from a script he wrote with star Youla Boudali, it follows two characters in the Greek town of Messolonghi. The first is police chief Elisabeth (Angeliki Papoulia), who we see in the opening scenes be exiled from her law-enforcement career in Athens; years later she’s still a square peg in the round hole of Messolonghi. The second is a quiet girl named Rita (Youla Boudali) who works in an eel processing facility; her brother, Manolis (Christos Passalis), is a local pop star. We see Elisabeth and Rita negotiating their lives in Messolonghi, with its various social complexities and patriarchal attitudes. And then a crime unites them, and various secrets of the town come to light.

This is a well-shot film, pleasant to look at with a kind of off-centred low-key energy — there aren’t many mannered symmetrically-composed shots here, but there’s a closeness to the characters that’s engaging. The actors shine, and Papoulia in particular comes off well, a weary dismissive cop with an anger that’s less smouldering than it is in a state of steady magnesium-like incandescence. Multilayered dinner parties are shot with an interesting sense of the social complexities and relationships of the speakers. Contrasting with this are brief scenes of dreams and visions.

And yet much of the film has the feel of a TV cop show — not an American network drama set in the big-city, but something like Inspector Montalbano or Broadchurch. Shows about cops in a small town, solving small-town crimes. Shows that lack the distinctive weirdness of Twin Peaks but that still dwell on the character of the investigators and suspects. Miracle of the Sargasso Sea is different in that the crime doesn’t happen at or before the beginning of the story, but instead relatively late in the film. At which point the paths of the two main characters, until then having nothing to do with each other, begin to converge.

This is an unusual structure which sounds worth trying, but to my mind it comes off as dramatically inert. Early on the different strands are interesting on their own but don’t inform each other, meaning neither really builds up any momentum. Then when the crime does happen, there’s no twist to it. We find out about a death, and the killer and motive are exactly what we imagine they are. The investigation goes about as one might expect. What could have been a subversion of genre ends up merely a dramatic structure that misfires.

I will note that I have seen other reviews that have a different assessment. Generally writers who saw more strangeness in the film had more of an appreciation for it. To me, the dream sequences and religious visions felt peripheral in terms of story structure and, to a large extent, character. They’re part of a symbolic picture, and the movie is at least engaged in trying to present a complexity of theme and image — the title, for example, is a reference to the life-cycle of eels, who migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. I felt these ideas were interesting, but did not add to the drama of the picture, while the drama itself did not add to their depth. In other words, the film remained basically realistic to me. If you as a viewer find more strangeness in it, you’ll probably have a higher opinion of it.

I will note that I have seen other reviews that have a different assessment. Generally writers who saw more strangeness in the film had more of an appreciation for it. To me, the dream sequences and religious visions felt peripheral in terms of story structure and, to a large extent, character. They’re part of a symbolic picture, and the movie is at least engaged in trying to present a complexity of theme and image — the title, for example, is a reference to the life-cycle of eels, who migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. I felt these ideas were interesting, but did not add to the drama of the picture, while the drama itself did not add to their depth. In other words, the film remained basically realistic to me. If you as a viewer find more strangeness in it, you’ll probably have a higher opinion of it.

I say all this because the film’s been associated with the Greek Weird Wave Cinema (Papoulia has been in three movies directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, one of the Weird Wave’s key figures), about which I must admit I know little. My uninformed opinion is that the movie’s more realistic in its approach to character and cinematography than I would expect from the Weird Wave. The symbolism’s a bit unusual in how it’s introduced, but is essentially straightforward.

The movie’s more interesting as a depiction of small-town life. It has a lot to say about patriarchal attitudes and about xenophbia, and the way these things are normalised — are in fact a part of the atmosphere. Messolonghi is shown as a place to get out of, a place the main characters desperately want to leave but can’t. It’s an unsparing portrait, but feels real; as a setting, the place is convincing.

The problem is that the film never finds a strong enough dramatic spark. For too long the movie’s a slice-of-life drama that splits its focus. Interesting ideas about character never quite develop. A situation’s established, and then is not explored so much as reiterated. Even the symbolic dimension, although extremely well-machined, doesn’t give the action the resonance it should. By the end, the lack of drama undercuts that symbol-structure and the film’s themes: the implication of society in the crimes of some of its most prominent members is attenuated. Oddly, because the characters are set up so well as individuals, they do not speak to structural societal issues. They seem to do what they do because of who they are, as opposed to being who they are because of the way the world made them.

The problem is that the film never finds a strong enough dramatic spark. For too long the movie’s a slice-of-life drama that splits its focus. Interesting ideas about character never quite develop. A situation’s established, and then is not explored so much as reiterated. Even the symbolic dimension, although extremely well-machined, doesn’t give the action the resonance it should. By the end, the lack of drama undercuts that symbol-structure and the film’s themes: the implication of society in the crimes of some of its most prominent members is attenuated. Oddly, because the characters are set up so well as individuals, they do not speak to structural societal issues. They seem to do what they do because of who they are, as opposed to being who they are because of the way the world made them.

Which is to say that there’s a disconnect between theme and character. I suspect this is the key point, for me. The characters are well-wrought, individually, and well-acted. Thematic ideas speak to both everyday human interactions and broader spiritual issues, by way of nature imagery. The story structure, to me most obviously flawed, still has some interesting ideas in its dual-lead approach and attempt to subvert genre expectations. All the ingredients for an excellent film are here. But they don’t work well together. Story and theme don’t inform each other in any complex way. Theme and character drift by each other. Drama and tragedy remain muted. This is the textbook example of a film less than the sum of its parts.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.