Fantasia 2019, Day 19, Part 4: Son of the White Mare

The last of the four movies I had on my schedule for July 29 promised to be interesting on any number of levels. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is an animated film made in 1981 by Hungarian Marcell Jankovics, directed by him from a script he wrote with László György. It’s based on the work of poet László Arany and folktales of the Magyars and Avars; Jankovics, who has published 15 books on comparative mythology, picked and chose from among the various versions of the tale to create what he wanted — a weird, protean, eye-popping, archetypal light show.

The last of the four movies I had on my schedule for July 29 promised to be interesting on any number of levels. Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is an animated film made in 1981 by Hungarian Marcell Jankovics, directed by him from a script he wrote with László György. It’s based on the work of poet László Arany and folktales of the Magyars and Avars; Jankovics, who has published 15 books on comparative mythology, picked and chose from among the various versions of the tale to create what he wanted — a weird, protean, eye-popping, archetypal light show.

The version presented at Fantasia was a new 4K restoration of the movie. Hundreds of hours went into cleaning and colour-grading the film, with the participation of Jankovics. When the movie originally came out it was not a box-office success, but it has since gained a high (and thoroughly deserved) reputation among animation fans; the restoration’s an important project, and the results are beautiful, doing the colours justice.

The story itself is a fairy-tale: a king and queen are deposed, and the queen in the shape of a white horse gives birth to a boy who grows into a hero by drinking her milk. He sets out to find his brothers and destroy the dragons who overthrew his father’s rule. This entails a long journey into a mysterious underworld, where he must rescue captive princesses, slay the dragons, and return.

Beyond the subject matter, the structure’s a fairy-tale as well. It’s generally cyclical, beginning with a child in a deep dark forest and ending with the restoration of the idyllic state of things before the saga began. The rule of threes is everywhere: three brothers, three princesses, three dragons. It begins with “Once upon a time” and ends with “they lived happily ever after.”

But then the way it’s made is something else again. The animation’s expressionistic, mostly in primary colours without black contour lines, shapes frequently neon-bright and often against dark backgrounds, sometimes strobing from one hue to another. The designs are almost Blakean, mixed with elements of art-nouveau.

Above all, more than in most animated films, there is a plasticity in what we see on screen: images shift into other images. Obvious cuts are rare. Added to the bright vibrant colours this creates a dreamlike sense in which nothing is stable, nothing permananent. As soon as you understand what you’re seeing it’s something else; everything always in the process of metamorphosis. ‘Psychedelic’ is a word often applied to the movie, and it is well-earned. It’s a testament to Jankovics’ direction that this is not simply exhausting, and is in fact easy to follow.

Above all, more than in most animated films, there is a plasticity in what we see on screen: images shift into other images. Obvious cuts are rare. Added to the bright vibrant colours this creates a dreamlike sense in which nothing is stable, nothing permananent. As soon as you understand what you’re seeing it’s something else; everything always in the process of metamorphosis. ‘Psychedelic’ is a word often applied to the movie, and it is well-earned. It’s a testament to Jankovics’ direction that this is not simply exhausting, and is in fact easy to follow.

Which isn’t to say that the movie’s easy to absorb at one sitting. Son of the White Mare is full to overflowing with ideas and creativity. Motifs recur, identifying characters and concepts; visual symbols bring out aspects of theme. The planet Saturn appears repeatedly, a reference to Jankovics’ theory that it represented an ancient divine adversary in early myth. Sexual imagery is clear, giving an earthiness to the surrealism.

It’s important to note that this isn’t a character-based story. There is not any real development or complexity to anyone in the film. Our hero is moderately clever and vastly strong, but not deep or individualised. The flatness is the point. This is an archetypal story, a myth rendered in light. That can be difficult to take at feature length, but there’s so much going on in the film around the characters, so much change and fluidity, that we almost need the characters to remain fixed. We can rely on them, and explore the strange myth-world alongside them.

And yet the different settings of the film — or at least the different chapters of the story — each feel different even though they’re all in a state of constant change. The early scenes setting up the kingdom, the forest where the hero grows up, the mountains where he meets his brothers, the underworld where he fights dragons, even the passage back to the surface — they’re all clearly different stages along the journey of the film, ending where it began. The forest is darker than the other sequences. The scenes with the brothers perhaps a little less dynamic in its background. The underground more barren, if only relative to the rest of the movie.

And yet the different settings of the film — or at least the different chapters of the story — each feel different even though they’re all in a state of constant change. The early scenes setting up the kingdom, the forest where the hero grows up, the mountains where he meets his brothers, the underworld where he fights dragons, even the passage back to the surface — they’re all clearly different stages along the journey of the film, ending where it began. The forest is darker than the other sequences. The scenes with the brothers perhaps a little less dynamic in its background. The underground more barren, if only relative to the rest of the movie.

Again, this helps bring out the sense of myth. Lacking a distinctive individual lead, the film’s sense of character is effectively displaced onto its setting. We get a sense of the development of the story and the heightening of the drama from the way the world around the hero changes.

I note that the dragons the hero ultimately confronts, the main villains who destabilised the natural cycle to start with, are each in different ways visual representations of the modern world. The story acquires a Tolkien-like feel, then, with the brutality of industrialism opposed to life-renewing nature. The myth-pattern restores the world to harmony. But the imagery of the film is itself influenced by modern artistic movements, and the story’s told through the modern technology of film; I wonder how much the dragons should therefore not be read as dragons of modernity as a whole but dragons of communism specifically. It’s easy to read state-sponsored ideology as the villain of a kind of nationalistic fable. The grey warmongering future is opposed by a traditional past with its traditional hero.

One can see problems, if so; nationalism has issues. And it is generally true that this traditional story does reflect traditional patriarchal attitudes, however lightly: males go off to have adventures, and it is the strongest, toughest male who gets to rescue passive women. There is a sense in which the film doesn’t challenge its source material, then, except insofar as its radical visuals suggest an individual approach to straightforward myth.

One can see problems, if so; nationalism has issues. And it is generally true that this traditional story does reflect traditional patriarchal attitudes, however lightly: males go off to have adventures, and it is the strongest, toughest male who gets to rescue passive women. There is a sense in which the film doesn’t challenge its source material, then, except insofar as its radical visuals suggest an individual approach to straightforward myth.

It’s interesting that one can see Christian echoes in a generally pagan story. The hero of obscure origins, the gathering of disciple-like allies, the suffering and sacrifice to attain victory, the reunion with the father. But then all these things also have other mythic parallels; one can talk about syncretism, or about archetypes manifesting in different mythic traditions. In any event this film has much to say about myth and its hero’s journey. It’s a startling visual experience that is unusual in capturing the flatness of fairy-tale and legend, the sense of unchanging characters in an unpredictable world — a world lacking the rules of logic that we take for granted in almost every other kind of fiction. Son of the White Mare has been justly hailed as a tremendous accomplishment for a long time; it’s nothing but good news that it will now be more easily available, in an ideal 4K version.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I love this film and I knew nothing about this restoration. Hope it gets a disc release.

His other films? Johnny Corncob is kind of similar but with simple flat colors.

Tragedy Of Man is very ambitious, stylistically varied but I didn’t feel it was as well executed as the other two.

I appreciate these reviews. Seen several of the really good ones (November, We Are The Flesh, Boxer’s Omen and a few other Shaw Bros ones).

Hope to see Mystery Of The Night.

Stunning animated film I saw recently: Keita Kurosaka’s Midori-Ko (not to be confused with the Suehiro Maruo adaptation, Midori)

https://www.midori-ko.com/trailer/

I got it on a French compilation called L’Animation Independante Japonaise volume 2, but it was very very expensive.

I forgot to ask, what did you make of the brothers spanking each other?

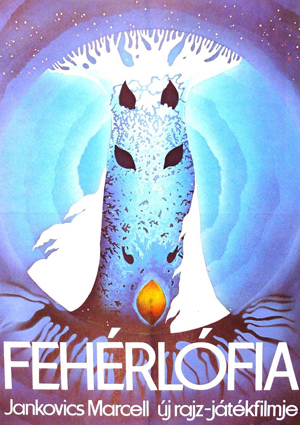

The poster is of a horse owl tree face thing ?

Robert Adam Gilmour: Thanks for the comments! I thought the brothers spanking each other was an interesting if odd kind of folkloric touch. I mean, it brings home that this is a different place and time.

Barsoomia: Yup, that’s the White Mare. Although it’s a still image, it gives you a bit of an idea of how images in the movie keep shifting into other images.

Very nice observation that the story’s changes seem to take place outside the characters, not within them. Interesting how many interpretations can be read into the film’s symbolism despite its basic storytelling. It definitely carries most of its meaning in its presentation rather than its plot, and it’s too bad that many people don’t notice that or can’t make sense of it.

I’ve been digging for info about the movie since coming across it a few years back, but literature about it is very sparse and most only talk about the visuals. Even the director’s own comments are spread across dozens of obscure articles and interviews. Some might disagree with his personal views, but I’m interested in them nonetheless, just to understand the movie better. For example, I didn’t even notice the film’s anti-pollution theme until I read one such interview, but afterwards it became very obvious. The visuals focus a lot on stars, planets, constellations and seasonal weather as symbols of folklore, and air pollution makes all of them less visible. That’s a clever way of symbolizing how modern technology can make us forget about nature and old traditions.

I hope this re-release will help shed light on not just the film but also the extremely tough production work and the thoughts that went into it, whether through the statements of its creators or through independent analyses and thoughtful reviews like this one. There’s plenty of stuff in it I’m still confused over.