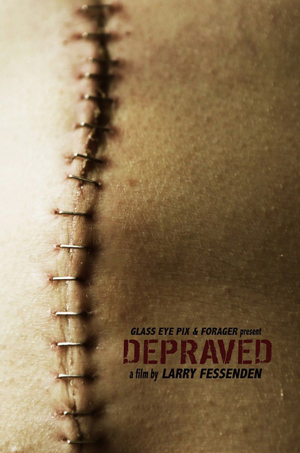

Fantasia 2019, Day 19, Part 2: Depraved

One of the things that most fascinates me about film is the way Frankenstein is at least as important in that medium as it is in prose. Obviously this importance is most visible in genre film, but it’s there one way or another in the mainstream too — consider Gods and Monsters. From at least 1910, when the story was adapted into a then-epic ten-minute movie, through the tremendously important 1931 Boris Karloff version, it’s a story that’s haunted cinema. One way or another the tale or the monster comes up regularly at Fantasia, whether in Guillermo del Toro talking about the monster as a religious figure, or a film using a 1977 version of the story as a metafictional conceit. So this year, in addition to a screening of the notorious 1971 Dracula vs. Frankenstein, there was Depraved: a straight-faced modern-day retelling of the Frankenstein story.

One of the things that most fascinates me about film is the way Frankenstein is at least as important in that medium as it is in prose. Obviously this importance is most visible in genre film, but it’s there one way or another in the mainstream too — consider Gods and Monsters. From at least 1910, when the story was adapted into a then-epic ten-minute movie, through the tremendously important 1931 Boris Karloff version, it’s a story that’s haunted cinema. One way or another the tale or the monster comes up regularly at Fantasia, whether in Guillermo del Toro talking about the monster as a religious figure, or a film using a 1977 version of the story as a metafictional conceit. So this year, in addition to a screening of the notorious 1971 Dracula vs. Frankenstein, there was Depraved: a straight-faced modern-day retelling of the Frankenstein story.

It opens with a man (Owen Campbell) and his girlfriend Lucy (Chloë Levine). They have a minor domestic disagreement; he leaves; is murdered; and then wakes up. He’s lost his memory, and is horribly scarred (and is now played by Alex Breaux). He was re-animated by a scientist named Henry (David Call), who names the reborn entity Adam. Henry has a friend named Polidori (Joshua Leonard, who began his film acting career way back with The Blair Witch Project), who’s responsible for acquiring funding for Henry’s one-man revivification project. That’s turning out to be tricky, though, and Polidori wants to take Adam public. As he argues with Henry about this, they along with Henry’s girlfriend Liz (Ana Kayne) educate Adam about human life and history. But will Adam be able to control his instincts? How will it all end?

In tragedy, of course, as it began. The film was written and directed by Larry Fessenden, and it’s an interesting straightforward science-fictional take on Shelley’s Frankenstein. Fessenden’s a veteran filmmaker (and actor, who appeared among other places in In A Valley of Violence) who has spoken about being influenced by the Universal horror films. His second movie, 1982’s Habit, was a vampire film; his first major feature with a full crew, 1991’s No Telling, was subtitled The Frankenstein Complex. This movie’s a more direct take on the story.

In some ways, though, it’s still very subversive. The fevered gothic atmosphere of the original, with its point-of-view anchored by Victor Frankenstein’s subjectivity, is gone. This is Frankenstein from the creature’s perspective, a rendering in which Adam’s humanity is key. Thus we do not have the frenzied moment of creation, no cry of “It’s alive!” There is a level, in fact, in which this movie undermines Frankenstein’s claim to create anything. Fessenden underlines the fact that Adam, or the raw material of his brain, had a life before Frankenstein ever got his hands on him.

Intriguingly, where Shelley’s novel had Victor Frankenstein haunted by his creature as though by a doppelganger, part ghost and part avenging angel and part his own shadow-self, here the scientist has a different sort of nemesis. Names in the film are drawn from the book — Adam for the creature, Liz or Elizabeth for the scientist’s girlfriend — except that the scientist here is named Henry, the name of the scientist in the 1931 film but also recalling Victor Frankenstein’s best friend, Henry Clerval. The scientist’s closest friend in Depraved is named Polidori, and the original John Polidori was not a character in the novel but a witness to its creation: he was Byron’s doctor, present at the evening of storytelling that gave rise to Frankenstein. Polidori wrote up his own contribution to the evening as a short story, “The Vampyre,” the first depiction of an aristocratic vampire (assumed to be a fictionalisation of Byron), but my point here is that the film links the friend and financier with the scientist: the film scientist takes the name of the friend in the book.

Intriguingly, where Shelley’s novel had Victor Frankenstein haunted by his creature as though by a doppelganger, part ghost and part avenging angel and part his own shadow-self, here the scientist has a different sort of nemesis. Names in the film are drawn from the book — Adam for the creature, Liz or Elizabeth for the scientist’s girlfriend — except that the scientist here is named Henry, the name of the scientist in the 1931 film but also recalling Victor Frankenstein’s best friend, Henry Clerval. The scientist’s closest friend in Depraved is named Polidori, and the original John Polidori was not a character in the novel but a witness to its creation: he was Byron’s doctor, present at the evening of storytelling that gave rise to Frankenstein. Polidori wrote up his own contribution to the evening as a short story, “The Vampyre,” the first depiction of an aristocratic vampire (assumed to be a fictionalisation of Byron), but my point here is that the film links the friend and financier with the scientist: the film scientist takes the name of the friend in the book.

The two men become doubles or counterparts. There is I think a sense in which the conflict of the film is Henry the scientist against Polidori the money-man; the ideal of science and research versus money and the practical world. Adam is pushed and pulled between them, and the climax at the third act sees the implicit conflict come to a full and violent boil. Worth noting at this point that Adam’s name in his original life, the man we see at the start of the film, was Alex Clerval.

At any rate it seems significant that the title of the film comes from Polidori’s attempt to educate Adam, taking him to a museum and to a strip club. In the museum Polidori reflects to Adam that human history is a history of violence and depravity. If that’s true, then nothing Adam does should come as a surprise, not even the murder of an innocent woman (named Shelley). Adam is human, and therefore is a monster. Indeed, when the film culminates in violence, we have been waiting for it, have been led to want to see Adam deal out justice; we are implicated in Polidori’s cynicism. In wanting to see pain and death meted out, in wanting to see the monstrous side of Adam, we face our own depravity. The title’s an accusation.

At any rate it seems significant that the title of the film comes from Polidori’s attempt to educate Adam, taking him to a museum and to a strip club. In the museum Polidori reflects to Adam that human history is a history of violence and depravity. If that’s true, then nothing Adam does should come as a surprise, not even the murder of an innocent woman (named Shelley). Adam is human, and therefore is a monster. Indeed, when the film culminates in violence, we have been waiting for it, have been led to want to see Adam deal out justice; we are implicated in Polidori’s cynicism. In wanting to see pain and death meted out, in wanting to see the monstrous side of Adam, we face our own depravity. The title’s an accusation.

That’s a tricky thing to get away with, but it more-or-less works here. Overall the film has slow moments, particularly as Henry and Polidori educate Adam, and it occasionally has a patchwork feel: it changes tones in different sections. Of course, one might well argue that this story of all stories has a right to a patchwork feel. More difficult perhaps are practical issues with Henry. It’s easy enough to accept him as a genius, but more difficult to accept that he works entirely alone on this project; even more difficult to accept that a project strapped for cash would base itself in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

Still, anchored by an excellent performance by Breaux, Depraved works. It’s a Frankenstein adaptation that exchanges thrills for intelligent speculation and thematic exploration, which is intriguing. It’s a low-budget take on the story that succeeds in feeling as though it says something significant both about the modern world and about human nature as a whole. It isn’t just scientists who must scramble to secure financing, after all, but also filmmakers. It is tempting to see an autobiographical element in Depraved, and by extension all film treatments of Frankenstein. Which is to say that the movie, removing many of the more intriguing aspects of the original, replaces them with new things. What more can an adaptation do?

Still, anchored by an excellent performance by Breaux, Depraved works. It’s a Frankenstein adaptation that exchanges thrills for intelligent speculation and thematic exploration, which is intriguing. It’s a low-budget take on the story that succeeds in feeling as though it says something significant both about the modern world and about human nature as a whole. It isn’t just scientists who must scramble to secure financing, after all, but also filmmakers. It is tempting to see an autobiographical element in Depraved, and by extension all film treatments of Frankenstein. Which is to say that the movie, removing many of the more intriguing aspects of the original, replaces them with new things. What more can an adaptation do?

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.