Superworld Comics

Hugo Gernsback, the self-proclaimed “Father of Science Fiction,” has been lauded a thousand times for publishing the first all science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories. Rightly so, for modern science fiction as a genre starts there. Amazing was launched in 1926, when Gernsback was 42. Gernsback lived another forty-one years and continued to throw off ideas as dervishly as in the first half of his life. Could it be that he has other, perhaps lesser-known, firsts to celebrate? Could it be that he also published the first all science fiction comic book?

Well, not quite. Pulp publisher Fiction House made a simultaneous launch of a science-fiction pulp, Planet Stories, cover-dated Winter 1939, and a comic book, Planet Comics, cover-dated January 1940, and so they get the credit. (The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction gives first place to the most oxymoronically-titled comic, Amazing Mystery Funnies. That featured several sf strips, but those were never even more than half the contents throughout 1939.)

I’m burying the lede. Hugo Gernsback published a comic book!

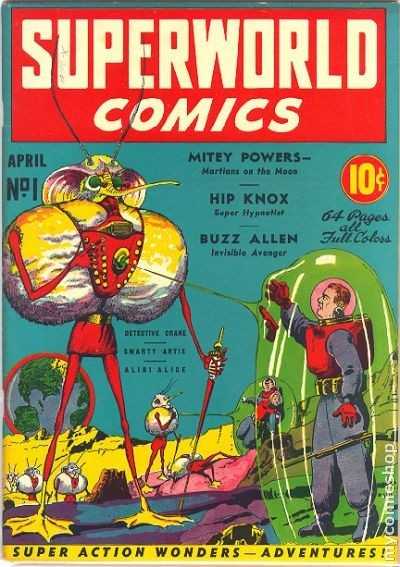

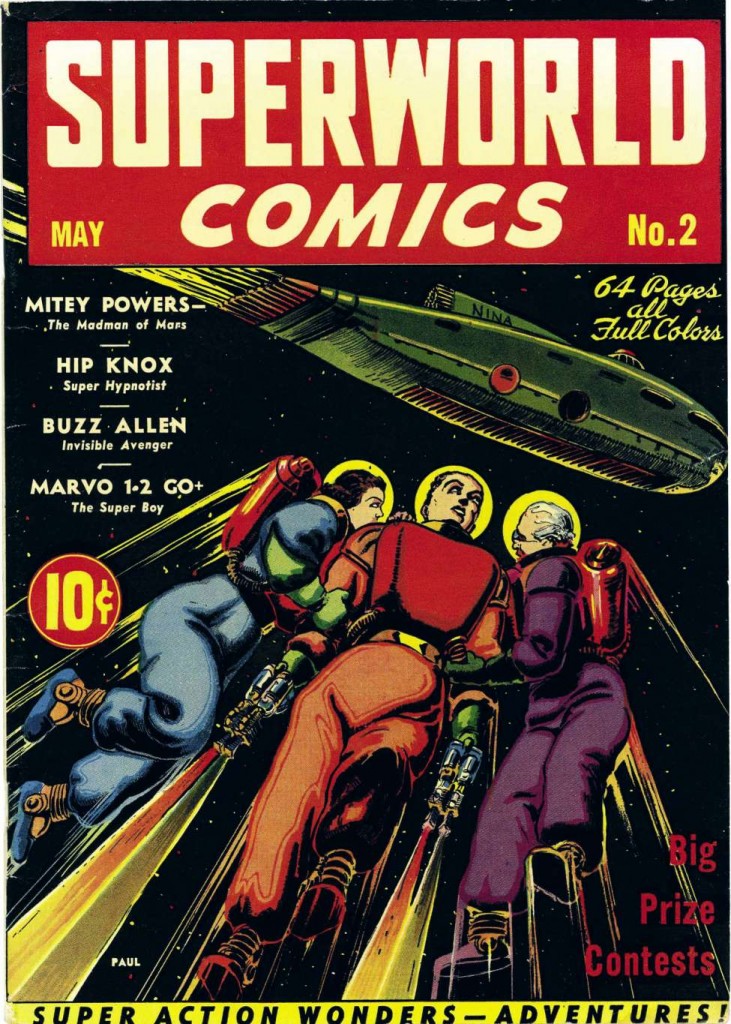

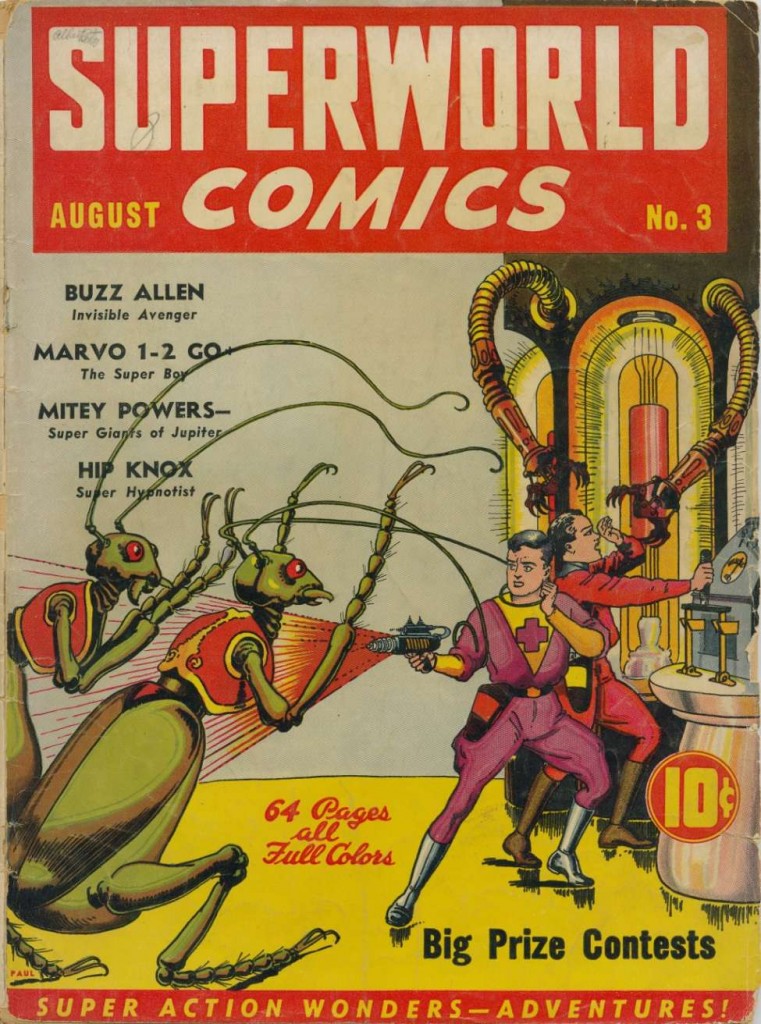

This must be the best-kept secret, maybe the only-kept secret, in the genre. It was news to me and I own a copy of Gary Westfahl’s Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction, which has half a dozen pages on the topic. Called Superworld Comics, published under the banner of Komos Publications, the first issue, cover-dated April 1940, hit newsstands on March 16, 1940. (Westfahl, in pre-internet days, could only get his hands on issue #1. Even with the internet, I found only #2 & 3. A collaboration across time and space!)

Gernsback was always an outlier in the world of pulp magazines, far more comfortable as a proselytizer of science and technology in his nonfiction publications. He didn’t mind sensationalizing what he believed were real advances that foretold the onrushing future, but he disdained the superscience and pseudoscience that his competitors hyped on lurid covers illustrating even more lurid fictions. His style of science fiction was quickly outmoded. Even in what is now thought of as the “gosh-wow” era, readers wanted more fiction and less science. Gernsback could never find it in himself to provide that. He wanted to teach and edify. In short, he was probably the worst choice in America to start a comic book.

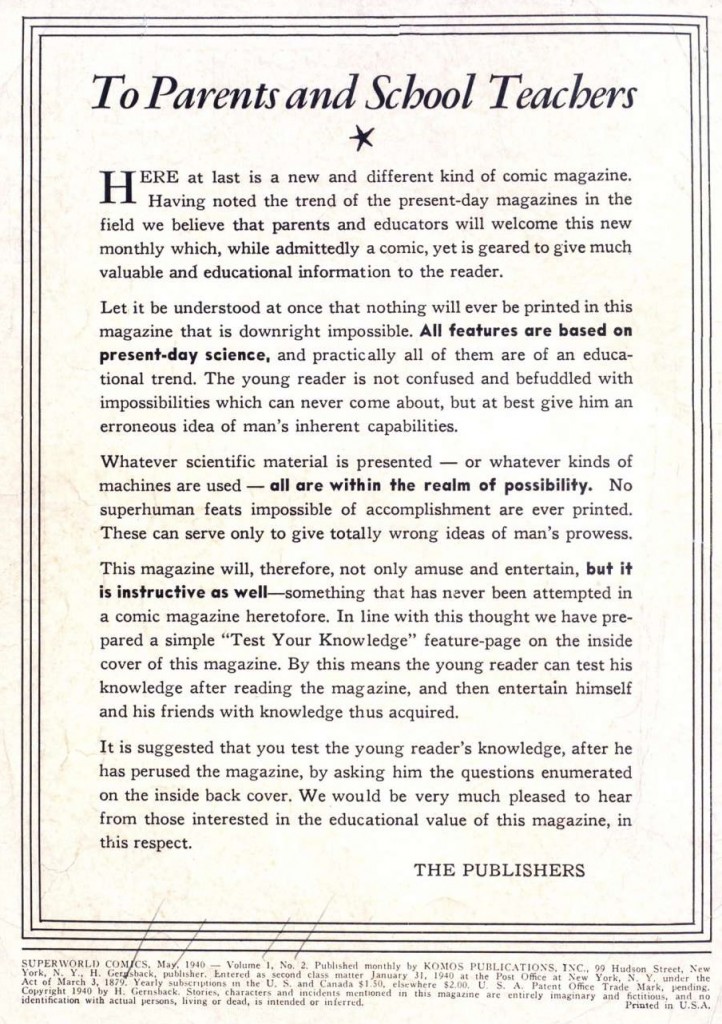

He proceeded to prove this truth as soon as Superworld Comics #1 was opened. On the inside front cover was this appeal.

Look at the bolded lines: “All features are based on present-day science,” “all are within the realm of possibility,” and “but it is instructive as well.” Not exactly what kids wanted. No wonder he aimed the page at parents and school teachers. Gernsback might have gotten away with this tosh if he were providing an early version of Classics Illustrated. He wasn’t, the proof right there on the hideous and lurid cover that was what the kiddies panted for and the adults abhorred. Maybe Gernsback should have swapped locations and put the editorial on the front cover and hidden the Martian menace on the inside.

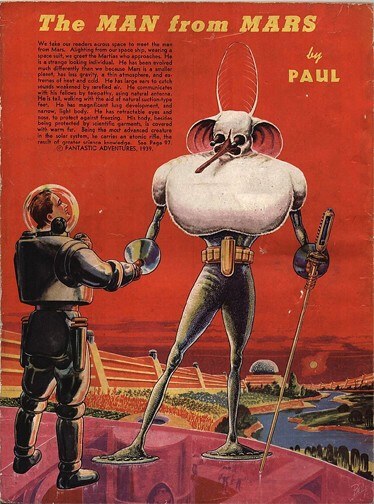

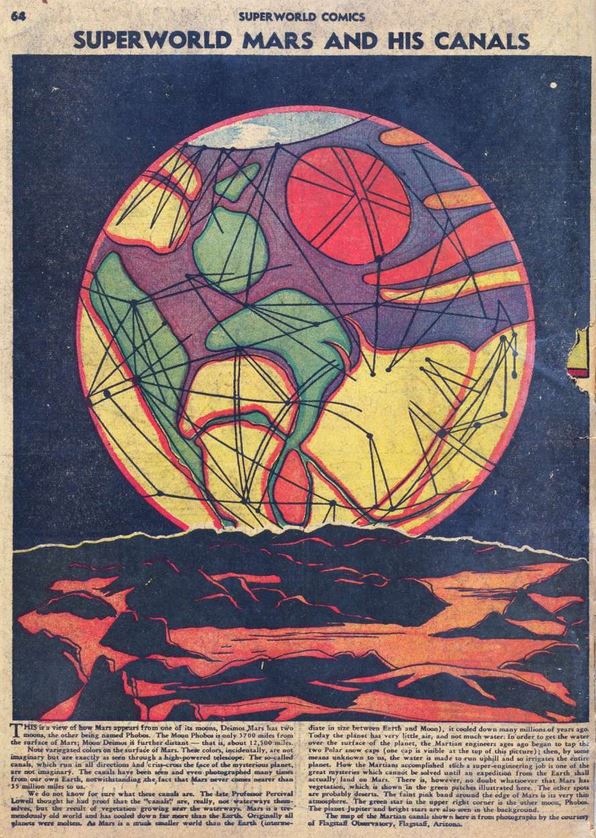

Gernsback, possibly blind to what decade he was in, went back to his more successful past and brought together the old crew. The aliens on the cover are unmistakably the work of Frank R. Paul. They were swipes from his own art, a one-page feature on the inside back cover of the May 1939 Fantastic Adventures, edited by Ray Palmer.

The text starts off with:

We take our readers across space to meet the man from Mars. Alighting from our space ship, wearing a space suit, we greet the Martian who approaches. He is a strange looking individual. He has been evolved much differently than we because Mars is a smaller planet, has less gravity, a thin atmosphere, and extremes of heat and cold. He has large ears to catch sounds weakened by rarefied air. He communicates with his fellows by telepathy, using natural antennae. He is tall, walking with the aid of natural suction-type feet. He has magnificent lung development, and narrow, light body. He has retractable eyes and nose, to protect against freezing. His body, besides being protected by scientific garments, is covered with warm fur. Being the most advanced creature in the solar system, he carries an atomic rifle, the result of greater science knowledge.

The irony that Ray Palmer, later the promoter of the Shaver Menace stories and much flying saucer woo, depicted a friendly encounter between man and Martian, backed by sober and solid extrapolation of the science of the time, while Hugo Gernsback printed a similar image reversed to make the two races stereotypical foes devoid of any rational science is as staggering as anything found in the field’s history.

The hypocrisy is almost as rank. “The young reader is not confused and befuddled with impossibilities which can never come about…” Gernsback tells parents. “No superhuman feats impossible of achievement are ever printed,” this in a comic titled Superworld. Yet the story that the cover illustrates, “Mitey Powers Battles the Martians on the Moon,” belies every word. Mitey’s girlfriend’s father, Professor Wingate, has determined that “meteors” hitting the Earth are actually missiles fired from the Moon. Mitey quickly builds a spaceship and hies himself to the Moon, where he is experimented upon by the Martians, doubling his “mental and physical abilities.” Plausible science at its finest.

Mitey Powers, and pretty much all of the original strip material in Superworld, was written by Wunderkind Charles D. Hornig. Science fiction as a genre has an endless history of teenagers not just publishing but making their reps before their 20th birthday, but Hornig’s precocious biography is tough to top. He was just seventeen when he started one of the earliest fanzines, The Fantasy Fan: The Fans’ Own Magazine. In Hollywood fashion, the editorial he wrote for the first issue, September 1933, caught Gernsback’s eye. He immediately hired Hornig as Managing Editor of Gernsback’s pulp sf mag, Wonder Stories. (Gernsback had ulterior motives. Doing so allowed him to fire David Lasser and replace him with a youth getting only half as much salary.) Most sf editors were also authors, but the only sf story Hornig wrote was “The Fatal Glance” in the February 1935 Wonder Stories, as by Derwin Lesser, probably an emergency space filler. Remember the pseudonym, though. (David Lasser/Derwin Lesser. That can’t be a coincidence but any reasons are buried as the second-best-kept secret in the field.) So young that he took evening classes to get his high school diploma while editing the magazine days, Hornig ran Wonder Stories into the ground by 1936.

He returned in 1939 as editor of Science Fiction Stories, which used Paul as cover artist and Derwin Lesser as author of the science articles. He also edited offshoots Future Fiction and Science Fiction Quarterly, which would seem to be enough work for anybody, but loyally hopped on board with Gernsback for his new project.

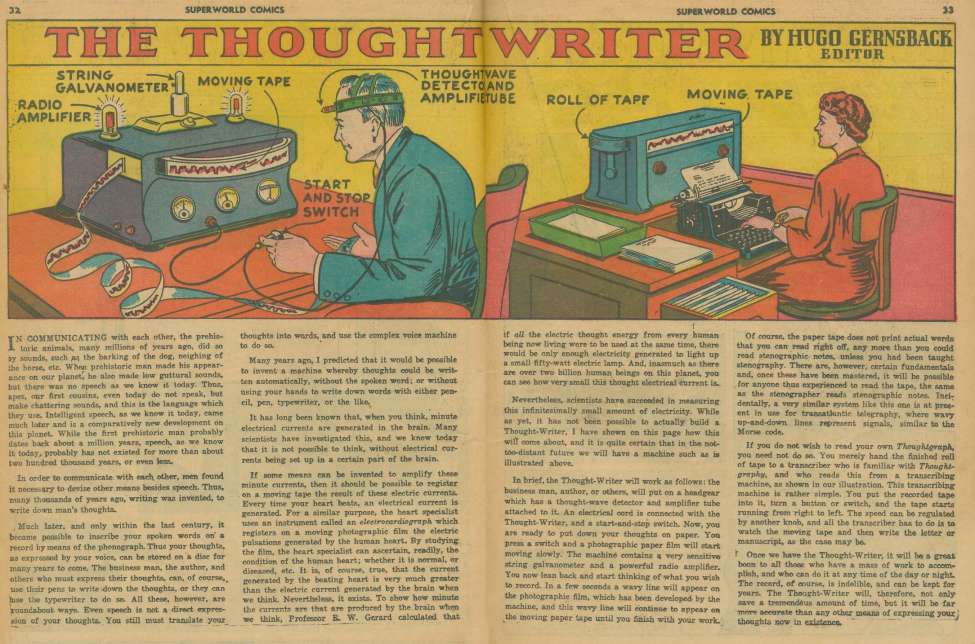

Mitey Powers is backed by “Buzz Allen The Invisible Avenger,” who has an invisibility belt; “Hip Knox the Super Hypnotist;” “Detective Crane,” just an ordinary guy; and “Marvo 1•2 GO+ The Super Boy of the Year 2680.” (I’m sure the 10-year-olds of 1940 picked up on the subtle homage to Gernsback’s “Ralph 124C41+ A Romance of the Year 2660,” published a mere nineteen years before they born. The plus in both cases mean one of the ten smartest people in the world.) Four of the five were presumably written by Hornig, even if some seem to have been produced by Derwin Lasser. Five strips aren’t nearly enough to fill the 64 pages of a 1940 comic, so he adds young girl’s strip “Alibi Alice” (written and drawn by a “Ruth Leslie” who has no other credits), young boy’s strip “Smarty Artie” (written and drawn by a “John Macery” who has no other credits), reprints Winsor McCoy’s famous, if ancient, newspaper comics strip “Little Nemo in Slumberland” (calling it “Little Nemo in Dreamland” for no apparent reason), and tops that with “Dream of the Mince Pie Field,” another McCoy comic, originally “Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.” Various features and quizzes take up a few pages. Gernsback being Gernsback, he couldn’t help devoting a couple of pages to sure-to-come inventions.

And some thoroughly not-up-to-date science:

As you must have noticed by now, the claim that this is the first all-science-fiction comic book doesn’t stand up to the mildest scrutiny. Only Mitey and Marvo are truly in the genre. Hip Knox and Buzz Allen were generic superhero types. (With that name, shouldn’t Buzz Allen at least have been an astronaut?) Their adventures were equally generic. Chase the bad guys, get knocked out/captured/doomed by the bad guys, heroically win against all odds on the last page. True, in Superworld #2, Hornig offers the readers tons of scientific facts about spaceflight before Mitey defeats Zaggar, the Madman of Mars. In Superworld #3, though, Mitey confronts The Super-Giants of Jupiter without Hornig bothering to wonder how thousand-foot-tall monsters could exist on a high-gravity planet. (Paul must have misread the note about what to draw on the cover. The giants become giant ants, nowhere to be found in the actual story. Perhaps the only documented case of stuttering in reading.)

Hornig has a worst crime up his sleeve than a mere scientific blunder. To defeat the giants, Mitey causally commits genocide, a caption on the penultimate page reading, “The Martian poison gnats hatch rapidly and within a few days countless billions of them will have been born, inflecting the entire population of Jupiter, killing off most of the people.” Don’t worry, parents and teachers: the last page of the story gets back to science facts.

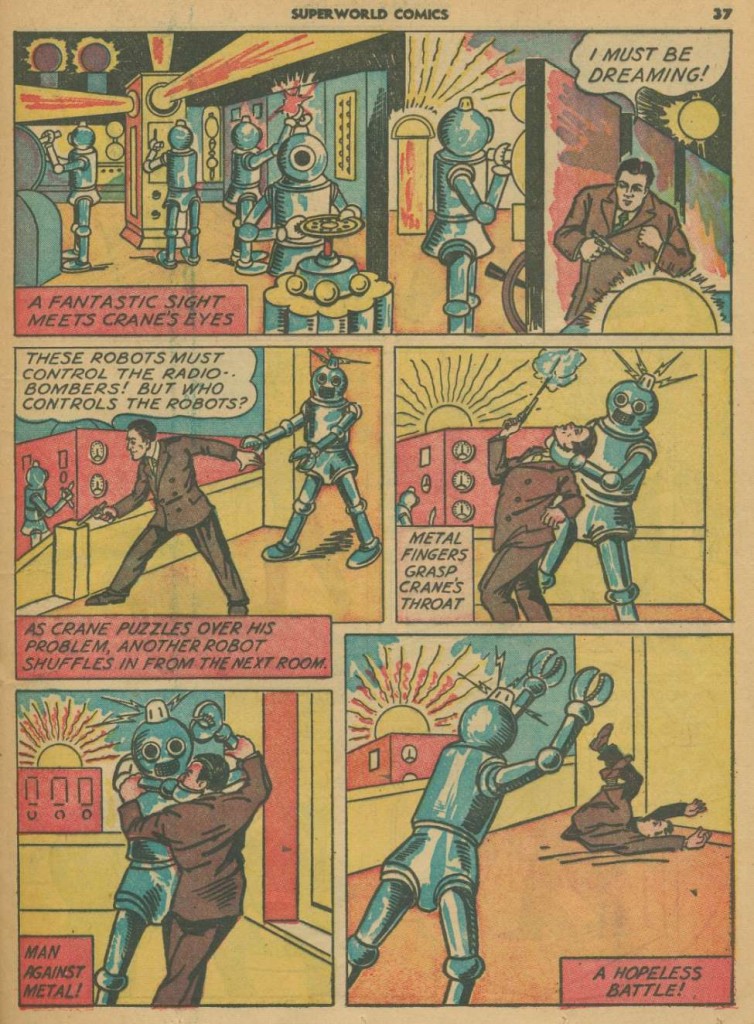

In this Bizarro universe of Hornig’s it shouldn’t surprise anyone that the only appearance of robots takes place not in outer space or the future, but in the adventures of Detective No First Name Crane, regular guy. Both art and story are attributed by comic databases to “Homer Porter,” who is normally assumed to be a pseudonym of Hornig. I’m extremely doubtful. The writing style is wildly different from that is Mitey and Marvo and Hornig has no other art credits anywhere. “The Case of the Radio Spy!!” was one of millions of similar stories during the war years about Nazi stand-ins sabotaging American factories. New York plain-clothes detective Crane isn’t much more than a cliché himself, a scientifically-minded action sleuth whose sleek “speed-plane” that takes off from a Manhattan roof is awfully similar to the Bat-Plane introduced just a few months earlier in Detective #31.

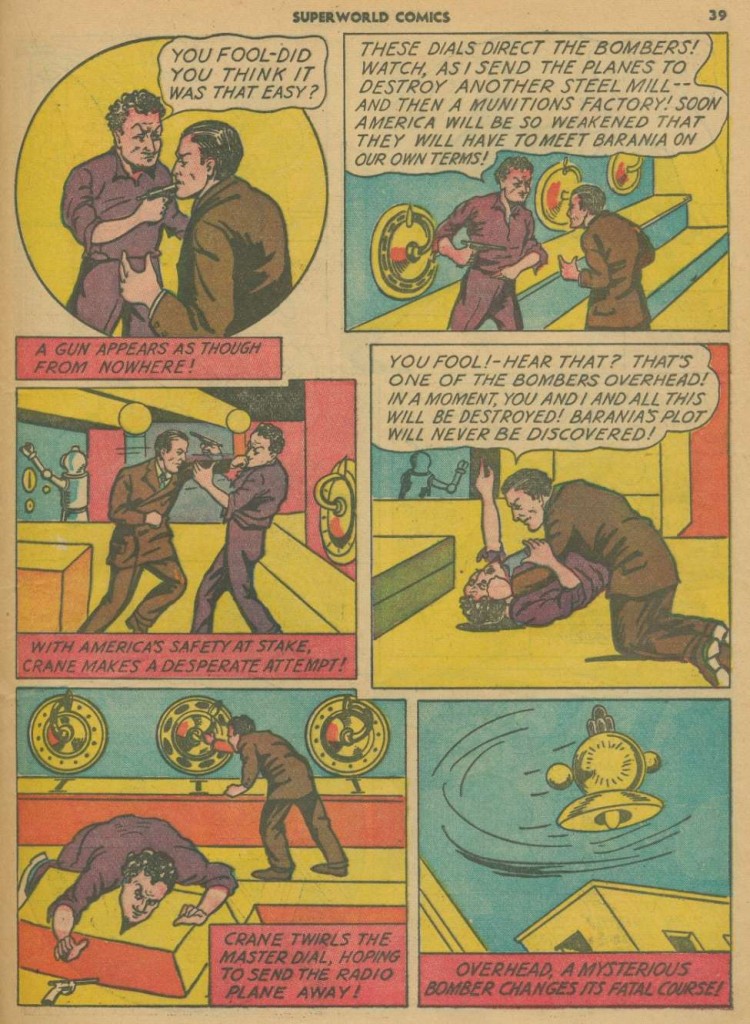

The villains always have the better technology, though. The spy from Barania has a squadron of flying-saucer-type bombers to attack the steel mills. The bombers are unmanned, controlled by radio from a secret location, found in about two seconds by Crane. He busts in and sees only… robots! Yes, robots, finally, only 1700 words in to this robot column! The robots are busily at work doing things, none of which seem likely to be radio-controls, but I guess I’m not the expert on such things that Homer Porter was. You’d also have to ask Porter why the Baranian spy is wearing a robot suit while hidden in his secret lair. None of it matters. We get lots and lots and robots, the good guys win, and who needs anything more?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How did heroes ever survive once the villains realized that putting a giant master switch within easy reach of a good guy wasn’t a great idea?

Superworld Comics released three issues and vanished in the middle of a continued story. Traditionally, three months were needed to get sales results back from the newsstands. The issues were dated April, May, and August 1940, though, and that August issue still proclaimed it a monthly publication. By then the end must have so been obvious that issue three was dumped on the market to pick up a last few pennies.

Comic books with original content were no more than four years old but already had increased tremendously in sophistication. What wowed ‘em in the 1920s looked dated and cheesy against a Superman fast becoming a national symbol. Being bad by the comic book standards of 1940 is a cringe-making achievement.

Hornig moved to California the next year, cutting all ties with the science fiction field, and with writing and editing more generally. He lived for another fifty years, popping up occasionally for a jaundicedly nostalgic look at Golden Age SF.

Gernsback launched Science Fiction Plus in 1953, which never saw 1954. Otherwise he too left the field after Superworld Comics. There was no active place for him except as a faded trophy that younger generations sometimes remembered to remove from the attic.

Robots, by contrast, were just getting going.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Feet: Pedipulator, Walking Truck His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is finally available wherever books can be ordered over the internet. Visit his companion site RobotsinAmericanPopularCulture.com for much more on robots.