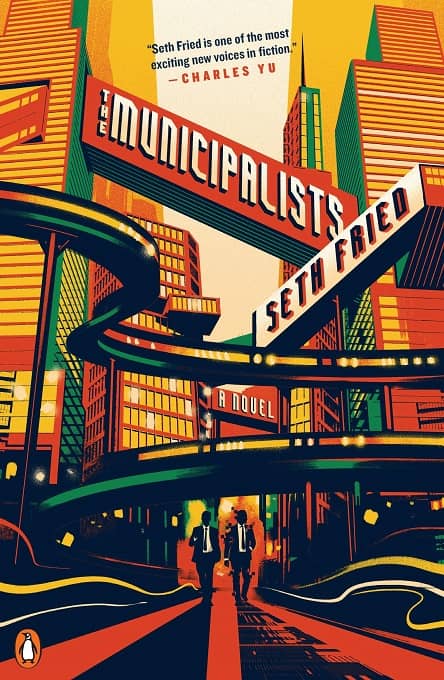

New Treasures: The Municipalists by Seth Fried

|

|

I’ve been slowing down my acquisition of new books recently, mostly for reasons of space. But occasionally a title will prove just too irresistible, as happened last week with Seth Fried’s debut, about a human and his AI partner on an adventure to save the great American city of Metropolis. It was Library Journal‘s “Debut of the Month,” and named one of the best books of the month by The Verge, io9, Amazon Books, Book of the Month Club, Tor.com, and others. Here’s Leah Schnelbach’s take at Tor.com.

The Municipalists, Seth Fried’s debut novel, is a futuristic noir that isn’t quite a noir; a bumpy buddy cop story where the cops are a career bureaucrat and computer program… It’s also deeply, constantly funny, and able to transform from a breezy page-turner into a serious exploration of class and trauma in a few well-turned sentences.

At first it seems like a wacky buddy cop book. The buttoned-down bureaucrat Henry Thompson is a proud member of United States Municipal Survey, traveling around the country to make improvements to city infrastructures… the kidnapping of a beloved teen celebrity [has] left the city reeling, only for people to be knocked truly punch-drunk by a series of terrorist attacks. The attacks and the kidnapping might be related. We’re soon taken all the way into sci-fi territory however when Henry gains a partner — a snarky AI called OWEN who is positively giddy about being sentient…

Seth Fried has been writing fiction and humor for years now, with excellent short work popping up in McSweeney’s, Tin House, One Story, and The New Yorker — his Tin House story “Mendelssohn”, about a Raccoon of Unusual Size, was a particular favorite of mine. His 2011 short story collection, The Great Frustration, was wildly diverse. Now with The Municipalists he proves that he can orchestrate a tight, complicated plot… Fried has also given us an endearing protagonist in Henry Thompson, and an all-time classic drunken AI, and if there’s any justice in the cities in this reality this will be the first book in a Municipalists-verse.

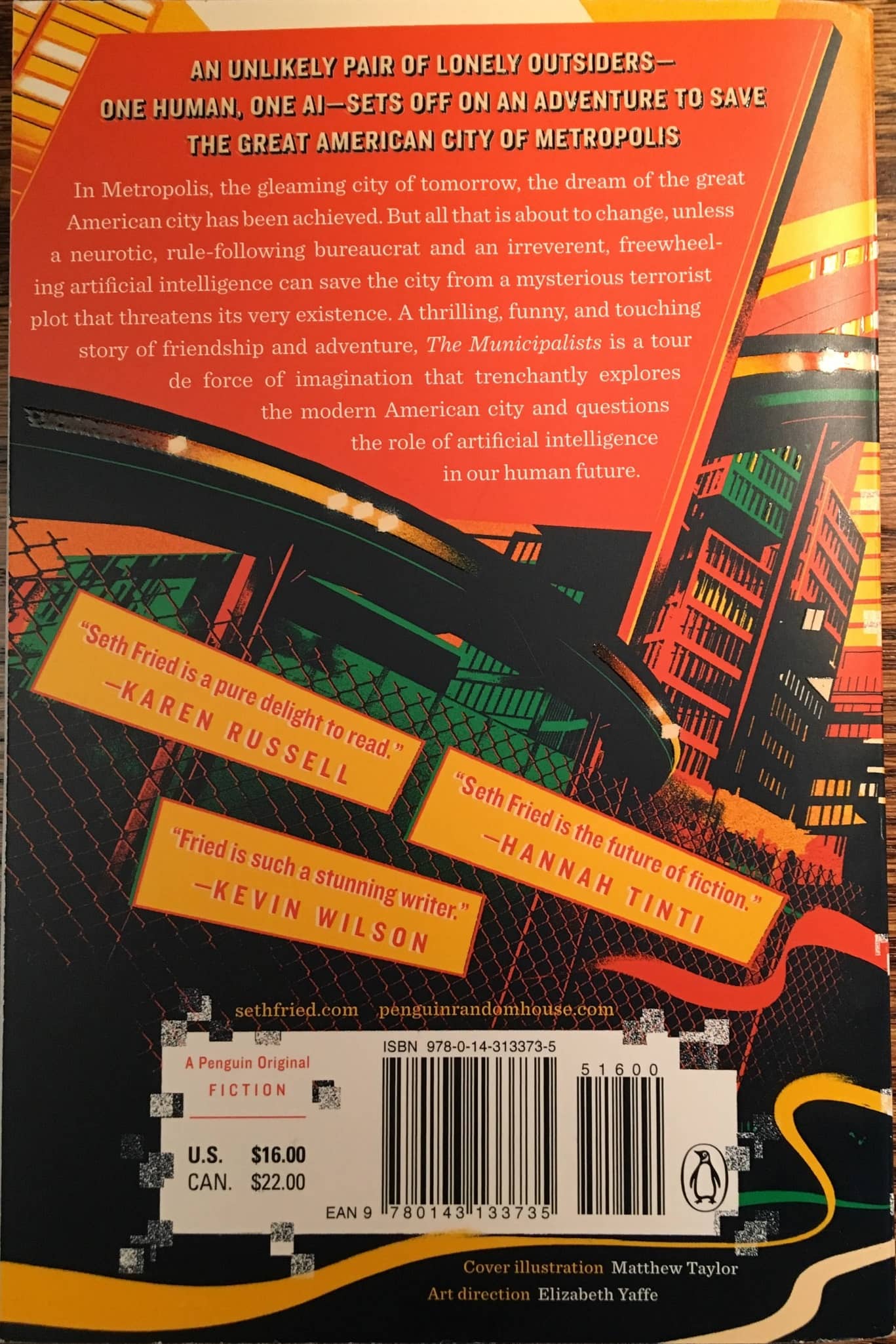

The Municipalists was published by Penguin Books on March 19, 2019. It is 265 pages, priced at $16 in trade paperback and $11.99 in digital formats. The cover is by Matthew Taylor. Read the first ten pages here, and see all our recent New Treasures here.

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

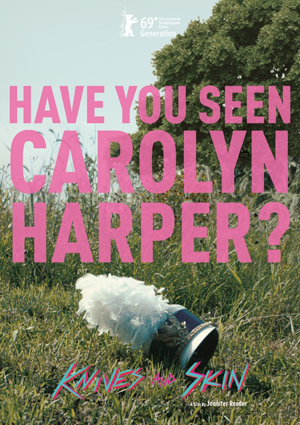

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes.

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes.

Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of

Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of

July 17 for me was a day of rest and running errands; then for my first film at Fantasia on July 18 I went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Maggie (메기). Directed by Yi Ok-seop from a film she wrote with star Koo Kyo-hwan, it’s the story of Yeo Yoon-young (Lee Ju-young), and her boyfriend Sung-won (Koo). Yoon-young’s a nurse at Love of Maria Hospital in Seoul. One day, an X-ray surfaces showing a man and a woman having sex in the X-ray room. The next day almost nobody comes in to work; the X-ray room’s a popular site for assignations, and everyone thinks they’re one of the figures in the X-ray. Yoon-young’s the only one who dares show her face, along with Doctor Lee (Moon So-ri). They end up forming an unlikely partnership as Maggie helps Lee learn to trust other people. Meanwhile, Sung-won finds work filling in sinkholes opening up in Korea, following an earthquake predicted by a catfish named Maggie — who also turns out to play an important role within the film.

July 17 for me was a day of rest and running errands; then for my first film at Fantasia on July 18 I went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Maggie (메기). Directed by Yi Ok-seop from a film she wrote with star Koo Kyo-hwan, it’s the story of Yeo Yoon-young (Lee Ju-young), and her boyfriend Sung-won (Koo). Yoon-young’s a nurse at Love of Maria Hospital in Seoul. One day, an X-ray surfaces showing a man and a woman having sex in the X-ray room. The next day almost nobody comes in to work; the X-ray room’s a popular site for assignations, and everyone thinks they’re one of the figures in the X-ray. Yoon-young’s the only one who dares show her face, along with Doctor Lee (Moon So-ri). They end up forming an unlikely partnership as Maggie helps Lee learn to trust other people. Meanwhile, Sung-won finds work filling in sinkholes opening up in Korea, following an earthquake predicted by a catfish named Maggie — who also turns out to play an important role within the film.