Fantasia 2019, Day 11, Part 2: The Boxer’s Omen

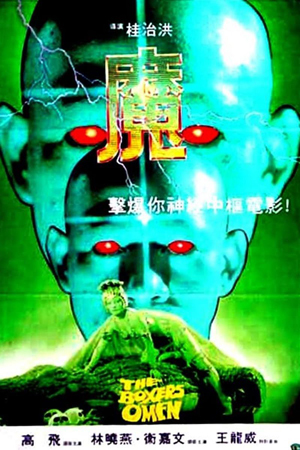

For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen Demon of the Lute, Buddha’s Palm, Flame of the Martial World, and Bastard Swordsman, as well as Five Fingers of Death. This year we got to see The Boxer’s Omen (Mo, 魔), from 1983, directed by Kuei Chih-Hung from his own story as scripted by Szeto On. Technically a sequel to Kuei’s film Gu, the English title hints at some of its influences: a bit of The Omen, a bit of Rocky, and a lot of low-budget exploitation film.

For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen Demon of the Lute, Buddha’s Palm, Flame of the Martial World, and Bastard Swordsman, as well as Five Fingers of Death. This year we got to see The Boxer’s Omen (Mo, 魔), from 1983, directed by Kuei Chih-Hung from his own story as scripted by Szeto On. Technically a sequel to Kuei’s film Gu, the English title hints at some of its influences: a bit of The Omen, a bit of Rocky, and a lot of low-budget exploitation film.

When Hong Kong gangster Chan Hung (Phillip Ko Fei) sees his brother crippled in a match with a cheating Thai kickboxer, Bu Bo (Bolo Yeung Sze), he travels to Thailand to challenge the evildoer to a revenge match. While there, weird visions lead him to a Buddhist monastery. It turns out that in previous lives Chan and the recently-deceased abbot were twins. This is a problem for Chan. The abbot killed the student of an evil wizard (Elvis Tsui), leading the wizard to then kill him with a spell that will now go on to kill Chan due to his linkage to the aforesaid abbot. Chan learns this from talking to the dead abbot, and after some confusion decides to become a monk to be able to defeat the wizard — but what of his match against the kickboxer who crippled his brother? And what about the wizard’s three living students?

This description of the plot barely hints at how bizarre, dreamlike, and transgressive this film is, but ideally gives an idea of how much scope there is for mystical goings-on. Rituals and spells are depicted with loving care, even when grotesque or indeed outright disgusting. But then a flashback in which the abbot fights the student and master wizards is simply surprising, as the duels involve crystals and puppets and wall-crawling and lurid lighting. On the other hand, an extended sequence shows the wizard’s students preparing a spell of revenge, which involves each of them eating and regurgitating food for the others to then ingest — and goes on from there, creating a demon inside a crocodile corpse, who Chan eventually must defeat. That of course comes at the climax of the film, in an ancient temple in Nepal, when Chan must engage in a magical fight unlike any I have ever seen.

What is most strange about the film is how it doesn’t feel like a straight-ahead exploitation film. Theoretically it should. There’s the gross-out bits, there’s a couple of violent kickboxing scenes, there’s a fair amount of nudity. And yet there’s also something else going on. I’ve seen some writers compare the film to Jodorowsky, and maybe that’s reasonable for the weirdness of it.

Then again, it might just come from Kuei’s involvement in the material. Supposedly he researched magic intensively for this film. Certainly there’s an intensity to the movie unusual in simple exploitation film, and elaborate sets and props and effects. Buddhist temples aren’t just venues for magical conflict, but also have richness and beauty and startling colour.

Then again, it might just come from Kuei’s involvement in the material. Supposedly he researched magic intensively for this film. Certainly there’s an intensity to the movie unusual in simple exploitation film, and elaborate sets and props and effects. Buddhist temples aren’t just venues for magical conflict, but also have richness and beauty and startling colour.

Conversely, I suppose you could argue that the black-magic gross-out scenes have the feel of actual forbidden rituals, a kind of equivalent to the Black Mass. I frankly do not have the knowledge base to understand how seriously to take the magical and religious themes of the movie, but it’s fairly clear this is not a complex meditation on Buddhist lore. It’s a strange mix of all kinds of things, elements of high culture along with lots of low culture, fused so that they cannot be easily distinguished.

This is not a good movie, as such. It never really had the chance to be a good movie. But it’s certainly a good movie of its type. And it’s a movie not like many other movies I’ve seen. It has the eagerness to entertain of a lot of Shaw Brothers films, and a similar arsenal of tools (though there’s much less hand-to-hand combat). But it also has a sensibility that’s different from the other movies. It’s maybe a little bit more intense, if not quite serious. Watching it’s a different experience from the other Shaw films I’ve seen at Fantasia: more hallucinatory. You’re either engaged with the movie or completely out of it. In watching something like Demon of the Lute you move back and forth, following the story, then being impressed by the athleticism of the performers, then chuckling at some effect or plot twist. I found The Boxer’s Omen a little different, probably in part because it’s much less light-hearted. I can’t say it really conveys deep themes, but besides the story being grimmer it does feel as though the director’s trying to communicate something more.

It’s also visually more extreme. The location shooting gives it a different feel than a lot of more studio-bound Shaw films. And that realism also makes the fantastic imagery feel more explosive, located in an actual world instead of the Shaw Brothers’ usual universe. So we see the extravagant make-up on the evil wizard, the blood spurting from eye-sockets, a demon-woman stripped of her skin, and it all has a specific effect from being anchored in some kind of vaguely recognisable physical reality. In most cases that goes without saying, but here I think it helps throw into relief how the earlier Shaw films worked.

It’s also visually more extreme. The location shooting gives it a different feel than a lot of more studio-bound Shaw films. And that realism also makes the fantastic imagery feel more explosive, located in an actual world instead of the Shaw Brothers’ usual universe. So we see the extravagant make-up on the evil wizard, the blood spurting from eye-sockets, a demon-woman stripped of her skin, and it all has a specific effect from being anchored in some kind of vaguely recognisable physical reality. In most cases that goes without saying, but here I think it helps throw into relief how the earlier Shaw films worked.

I don’t know whether seeing it in 35mm (the first screening of the film in Canada in 35 years, incidentally) was ideal, or whether it would have been better seeing some sort of high-quality digital restoration. It’s interesting enough as a film that it deserves that kind of attention. But then the 35mm format was the original way to watch the movie, what the filmmakers must have intended. It’s a perennial debate, I suppose, but more relevant here than in most cases. This is not a movie to watch every day, or even most days. And it’s not going to be to every taste, or even most tastes. But it’s a fascinating thing to have exist in the world.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

A favorite of mine and definitely much better than Gu/Bewitched. Both films have an anti-promiscuity thing going on that feels like an excuse to show sex.