Feet: Pedipulator, Walking Truck

“Machine Walks on Moon” doesn’t have nearly the headline power as “Man Walks on Moon,” but for a short time in the early 1960s the U.S. Army funded a project for a moon walker.

The “Pedipulator,” as General Electric’s ordnance department in Pittsfield, MA, called it, was a concept vehicle. The concept, all but admitted in so many words by ordnance GM Gene R. Peterson, was to pump money into GE. Cold war spending in the US/USSR missile race had boosted employment in the department by 250%. They needed something to do. So they turned, once again, to the incredibly fertile mind of Ralph Mosher, whose Man-Mate, Handyman, and Hardiman I talked about in my last column.

Mosher was probably the country’s foremost engineer in the area of industrial manipulators, machines that were controlled by the arms and hands of operators who used feedback from sensors to control giant machine arms and grippers with incredible precision. Insider jargon called them Cybernetic Anthropormorphous Machines (CAM). They multiplied human strength by a factor of up to 60, making the operator virtual superheroes. GE’s flaks knew that commanded attention. An unsigned 1962 article appearing in many newspapers – undoubtedly a reprinted GE press release – is headlined, “Manlike Giant Machine Is Visualized Doing Superhuman Tasks of Creators.”

Exactly what those tasks would be remained cloudy. Surely they had to be good for something spectacular. Look at how big they were! Bigness counted for everything in those days. The moon walker could carry the three astronauts slated to land on the moon in the far-off Apollo project. And what about Vietnam? A land without good roads, but with rugged and varied terrain. A Pedipulator might scurry along at speeds up to 35mph, containing the soldiers within the safety of solid steel and bulletproof glass.

That cartoon of an outhouse with a view walking on bathroom plungers must have shaken the Army. Six months later in 1962, the moon walker resembled a caterpillar, a string of Pedipulators connected to create a better balanced six-legged vehicle with plenty of cargo space.

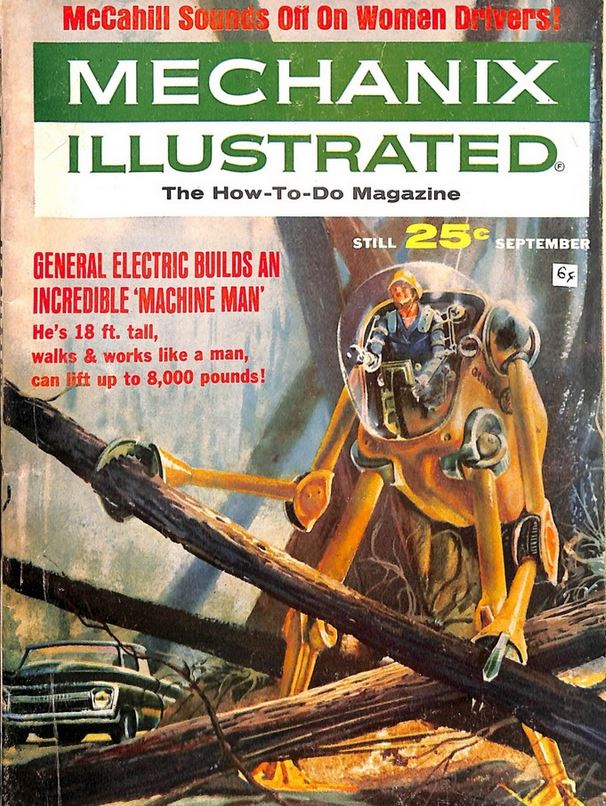

That drawing misleads readers into thinking that the Pedipulator has hand controls for the astronaut. In fact, the operator crawled inside a full-body suit. Hands and arms, legs and feet needed to be coordinated to move all the various parts. The September 1964 issue of Mechanix Illustrated had a more accurate depiction on its cover. (Note the “McCahill Sounds Off On Women Drivers!” banner at the top of the page. Culture changes over time as drastically as technology.)

The Pedipulator isn’t quite as silly as it looks. The difference between it and a pair of stilts lies in the feedback mechanism. Mosher’s Handyman could pick up a pencil by feeling how to grip it. The sensors in the Pedipulator’s feet would presumably guide the leg’s placement by testing and feeling the ground ahead just as humans walk in uncertain terrain. Besides, the Pedipulator, GE claimed, could bring itself back to a standing position if it got knocked over.

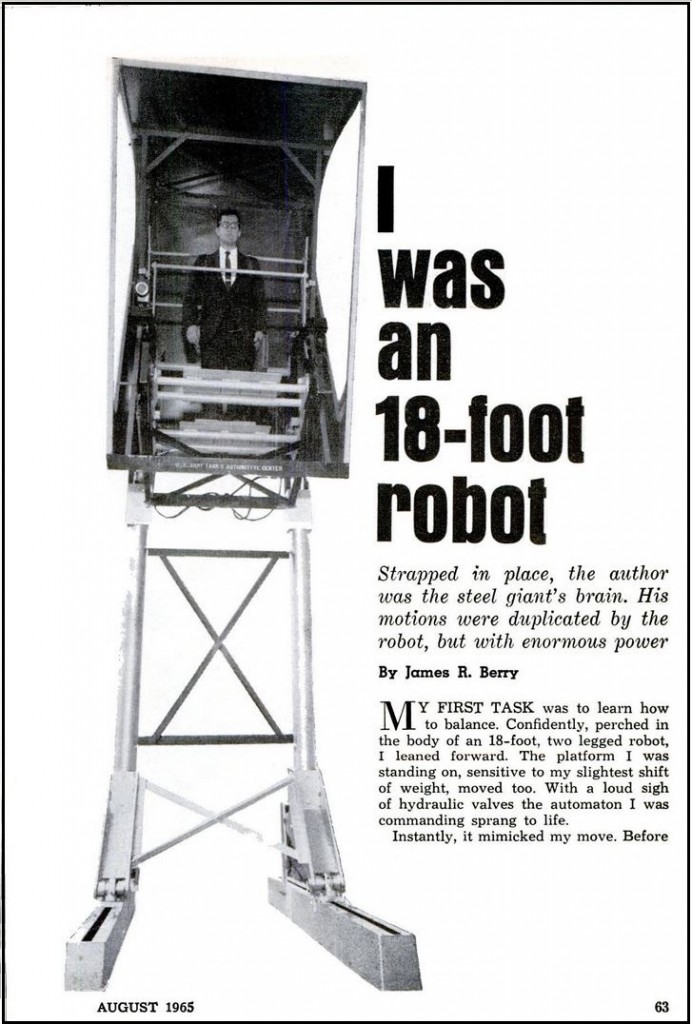

For better publicity, GE invited a reporter, James R. Berry, to test one, leading to one of the greatest headlines in Popular Science or any other magazine, “I was an 18-foot robot.” Berry’s first attempts were clumsy, even fatal outside a test situation, but he quickly got to the point of directing the Pedipulator through a series of maneuvers “as outlandish as the latest discotheque dance.” Though that sounded good and Berry even wrote that a working robot could no doubt be available in a year or two, the test was almost as phony as one for perpetual motion. An astute reader might wonder what exactly was making those dance moves, since the Pedipulator’s feet were fastened firmly to the floor. The arms, as seen in the picture, hadn’t even been bolted on. It couldn’t fall over or get up again.

Even the Army, better at spending money than at any other single task, balked at the Pedipulator. The long legs may have been intended to clear obstacles, but they also made the center of gravity far too high, leaving the machine all too susceptible to being knocked over. An 18-foot height also limited its passageways. How could one pick up fallen logs in a forest if one couldn’t travel through a forest? The Pedipulator was quietly shunted off to a corner of a warehouse, never completed.

GE had no reason to fear losing its valuable contracts, not as long as Ralph Mosher could talk anybody into anything. Height and balance the problems? How about lowering the height and adding an extra pair of legs. Presto. Or more accurately, after five years of additional Army contracts, GE reappeared in Popular Science, March 1969, with “The Fabulous Walking Truck.”

The 3,000-pound walking truck … can balance on two legs, and it can walk over and around large obstacles. It can walk forward and backward, and it can turn around. Top speed is five m.p.h. It can carry a 500-pound payload, and lift loads up to 500 pounds with one foot. It can drag a 1,000-pound load across a floor.

The power unit is a 90-hp. gasoline engine that drives a pump for a high-pressure hydraulic system. The legs are moved by hydraulic actuators…

The actuator servos are hydromechanical and need no electronic elements.

Here it is in impressive action.

GE loved the idea so much that it ran ads in prestigious magazines featuring a vaguely zoomorphous beastie emerging out of the fog of the past relentlessly marching into the future.

Mosher had finally done it. He created the ultimate turkey.

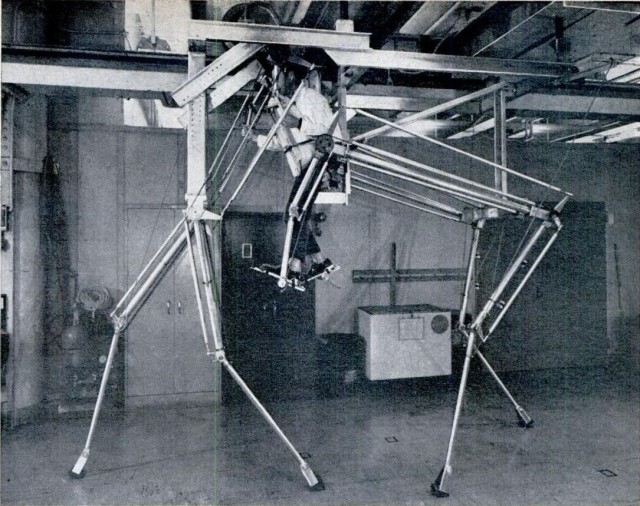

Operating the walking truck was far more difficult than the relatively simple Pedipulator. Thomas Rid described the process in Rise of the Machines. This picture of the training skeleton helps to make clear how it worked. Note that it is supported from above so that it can’t collapse during training.

[T]he operator had to climb into the machine’s belly on a small metal ladder than could be flipped down, suspend himself inside the skeleton, slip his feet into a pair of metallic holsters, and hold on to two joystick arms with handles and a number of triggers. The rider then revved up the 90-horsepower gasoline engine, pumping hydraulic fluid into the cyborg’s body and legs, through a tangle of tubes and gauges and valves, bringing it to a high-pressured life. When the rider raised his right leg, the machine raised its right hand leg. When he turned his left forearm, the machine turned its left foreleg.

About 10-15 hours of training were needed to properly operate the walking truck. Only one GE employee ever mastered it: Ralph Mosher. “You imagine you are crawling along the grounds on all fours – but with incredible strength,” he boasted. It’s a tribute to his obsession with his devices that he managed that. Despite the mechanical boost provided by the hydraulics, the sheer physical force required drained operators within fifteen minutes. Nor was crawling the proper analogy. A crawling object has a low center of gravity and doesn’t have to be especially careful where its legs land. The long, spindly legs of the walking truck required great precision lest they land on uneven turf. That precision was next to impossible because the operator had no way of seeing where they touched down. The video above dazzles while obscuring that reality. The operator shows complete control of the arms but performs no tricks with the legs.

Another fatal flaw of the prototype for military use lay in the hydraulic fluid. So much fluid needed to be pumped during operation that it couldn’t hold enough for sustained movement. In the lab GE hooked up external tanks and promised to solve that issue for the field, but it left the military shaking their heads in disbelief.

Only a single prototype was completed, and it apparently never even got outside the building to test on real ground. You can see it today in the U.S. Army Transportation Museum in Fort Eustis, Virginia.

It’s safe to say that the military, after more than a decade of funneling money into Mosher’s failed projects, became disgruntled at this point. GE’s crowing in newspaper and magazine articles stops entirely. So do mentions of Mosher. The next time he makes the news, it’s in 1972, when he left GE to start-up his own company to manufacture industrial manipulators. The name of the company? Robotics, Inc.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Hands: Yes Man, Handyman, Hardiman His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is finally available wherever books can be ordered over the internet. Visit his companion site RobotsinAmericanPopularCulture.com for much more on robots.

![1962-01-31 [Pittsfield MA] Berkshire Eagle 1 pedipulator headline](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1962-01-31-Pittsfield-MA-Berkshire-Eagle-1-pedipulator-headline.jpg)

![1962-07-24 Allentown [PA] Morning Call 21 pedipulator illus cropped - Copy](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1962-07-24-Allentown-PA-Morning-Call-21-pedipulator-illus-cropped-Copy.jpg)

![1962-07-30 Beatrice [NB] Daily Sun 2 pedipulator illus](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1962-07-30-Beatrice-NB-Daily-Sun-2-pedipulator-illus.jpg)