Fantasia 2019, Day 10, Part 2: The Born of Woman 2019 Short Film Showcase

On the afternoon of Saturday, July 20, I passed by the De Sève Theatre for the Born of Woman 2019 series of short genre films directed by women. It was the fourth iteration of the showcase, and in four years it’s become a hot ticket; I nearly didn’t get in. But there was just space enough in the end, and so I was able to see the collection of 9 films representing half-a-dozen countries.

On the afternoon of Saturday, July 20, I passed by the De Sève Theatre for the Born of Woman 2019 series of short genre films directed by women. It was the fourth iteration of the showcase, and in four years it’s become a hot ticket; I nearly didn’t get in. But there was just space enough in the end, and so I was able to see the collection of 9 films representing half-a-dozen countries.

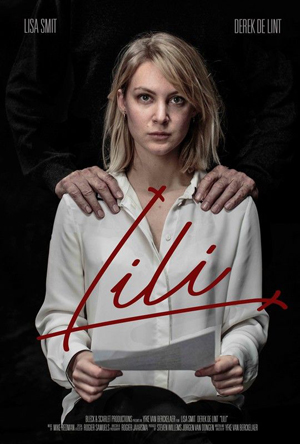

The showcase started with “Lili,” a 9-minute piece written and directed by Yfke Van Berckelaer. An actress (Lisa Smit), Lili, comes to audition for a role. The camera’s fixed on her, the man (Derek De Lint) she’s reading for unseen. He seems receptive to what she brings on her first reading, but has her try the dialogue again, and again, pushing her more and more. You can see what’s coming, and what the reversal will be, but the movie works because the slowly pushing-in camera’s a disturbingly effective point of view, because Smit in particular is very good in her part, and because the dialogue’s cleverly and subtly ironic.

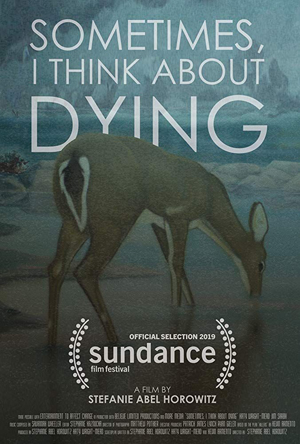

The art of sequencing a short film showcase can be overlooked, but in this case the arrangement of the shorts (most of which, in my opinion, were extremely strong to start with) was perfect. A good case in point was following “Lili” with the melancholic “Sometimes, I Think About Dying,” a 12-minute story from director Stefanie Abel Horowitz from a play by Kevin Armento, adapted by Horowitz, Armento, and Katy Wright-Mead, who also stars. It’s the story of Fran (Wright-Mead), a quiet, depressed woman who makes a connection with a male co-worker, Robert (Jim Sarbh). Will she be able to come out of her shell enough to maintain a relationship?

The movie’s almost unbearably painful in its portrait of a woman lacking in self-confidence. At the same time, Fran’s oddly sympathetic, so that by extension Robert feels like a lifeline for her. The orbit of the two of them is well-crafted, and the film really lands solidly because it knows where to end — not just what point of the story, but what seems like the exact right frame of film to end on.

Then different again was Australian writer-director Adele Vuko’s “The Hitchhiker,” about three women driving through the night to reach a music festival. Jade (Liv Hewson), the driver, picks up a hitchhiker (Brooke Satchwell), in part to distract her friends from innocent questions cutting near to a secret Jade doesn’t wish to reveal. The hitchhiker has a secret of her own, though, which only becomes clear once the friends pull in to a roadside bar.

This is a funny and occasionally gory movie that builds to a strong choice by the lead character. It’s also shot very nicely, with lurid glow-stick and neon colours. A very solid supernatural horror-comedy, it touches on some serious ideas, just enough to give the movie a real darkness. It’s entertaining, but downbeat enough to be memorable as a bit more than that.

This is a funny and occasionally gory movie that builds to a strong choice by the lead character. It’s also shot very nicely, with lurid glow-stick and neon colours. A very solid supernatural horror-comedy, it touches on some serious ideas, just enough to give the movie a real darkness. It’s entertaining, but downbeat enough to be memorable as a bit more than that.

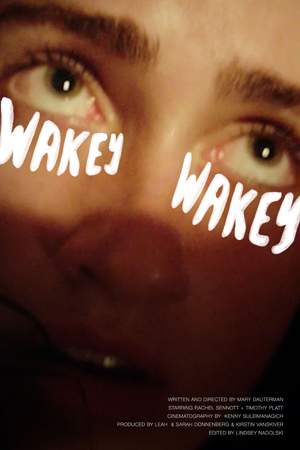

Next was “Wakey Wakey,” a surreal 4-minute short from writer-director Mary Dauterman. It begins with a woman, Alex (Rachel Sennott), urging her boyfriend Elliot (Tim Platt) to wake up, and then proceeds to get very strange very quickly. I did not entirely follow the dream-logic at work, but I can say that the sense of distrust of the woman for her boyfriend comes through clearly. And I can say it’s shot nicely, in a clear bright light.

After that was writer-director Hweiling Ow’s “Vaspy,” a story about a pregnant woman (Ria Vandervis) who finds a weird wasp-like figure among her young son’s toys, and develops strange cravings. At 11 minutes, I felt the pacing was too languid, and the conclusion was somewhat trite. It felt obvious in the wrong places, although Vandervis’ performance is fine, and the arid visual setting is subtly effective. But there was nothing too surprising or ultimately unsettling.

“Maggie May” followed, written and directed by Mia’kate Russell. After her mother dies, Sam (Katrina Mathers) decides to take her kids and move in with her sister Maggie May (Lulu McClatchy), who had been living with their mother. Things do not go as Sam planned. This is a solid parable about the need to take action when things are going wrong, and the way in which life necessarily involves interacting with others. It is not subtle, which would normally be fine, but at 14 minutes the film feels a bit long. Still, one can argue that the length is necessary to show how far certain things go, and to wring out as much horror as possible.

Erica Scoggins directed and wrote the next film, “The Boogeywoman.” In a roller-skating rink in a small town, a girl (Amélie Hoeferle) gets her first period; some of her friends are supportive and some are not; the legend of a monster called the Boogeywoman is whispered among the teens; and increasingly dreamlike events are set in motion. The movie’s a very strong sensory experience, if a little reminiscent of David Lynch (down to the musical sensibility). The depiction of the monstrous feminine strikes me as traditional, but effective — the weight of myth comes in part from its archetypal nature, and Scoggins is fairly consciously playing with archetype in this tale, notably in the way the characters come together in the end. The narrative’s open-ended, to my mind, not quite a fairy tale, not quite a horror story, but trembling with the potential of developing into either.

Then came “The Original,” directed by Michelle Garza Cervera from a script by Andrew Fleming. It’s a black-and-white movie set in a future in which Alana (Ariana Lebrón) is in a relationship with Gwendolyn (Rebecca Layoo). Alana bribes a jaded doctor (Ingrid Evans, who just about steals the show) to perform a risky procedure, but things go wrong, and Alana’s faced with a terrible choice.

Then came “The Original,” directed by Michelle Garza Cervera from a script by Andrew Fleming. It’s a black-and-white movie set in a future in which Alana (Ariana Lebrón) is in a relationship with Gwendolyn (Rebecca Layoo). Alana bribes a jaded doctor (Ingrid Evans, who just about steals the show) to perform a risky procedure, but things go wrong, and Alana’s faced with a terrible choice.

Visually, this is quite a stylish film. And the performances are very strong. But the basic idea is too familiar, and strains credibility — I don’t understand how it’s supposed to be an issue, and while I suppose it’s possible to read Alana’s choice as an indictment of the character and her society, I’m not sure that’s what’s intended. This is frustrating, given how strong the rest of the film is; how lovely it is to look at, and even how well-structured the story is. It reminded me of watching certain episodes of the original Twilight Zone — an incredible amount of craftsmanship and indeed artistry, but you can see the ending coming. The Twilight Zone has the valid excuse of being 60 years old. For this one, I can only return to the subversive reading of the film, in which it’s an extremely bleak satire.

Finally, the last short was one of the strongest films of any kind I saw at Fanastia this year, and indeed perhaps the strongest. Directed by Valerie Barnhart, “Girl In the Hallway” is based on a text written and performed by poet Jamie DeWolf. It’s a true story, here recounted in a voice-over above powerful and visually stunning animation, in which DeWolf was tangentially involved in events subsequent to the disappearance of a young girl from the tenement he lived in. Barnhart’s intelligent and creative artwork gives DeWolf’s story a new dimension. Metaphors used by DeWolf become recurring motifs in the film, creating a specific tone: fairy tales and Little Red Riding Hood become fused with everyday realities, including the terrible realities of violence and death.

Thanks to the phantasmagoric animation style the disturbing story of an overlooked child becomes more than simply hard-edged realism, almost a kind of mythopoeic night terror. The images are shadowy, primarily dark smoky greys, and the figures constantly metamorphose from one thing into another like clouds or dreams. There’s a childlike feel to them, mostly, and specifically the feel of a child’s nightmare. The film is claustrophobic, in that it has a sense of closeness and of incipient disaster, but it’s claustrophobic with the weird euphoria of oxygen deprivation. This is a world always shifting from one thing to another, a hallucinatory reality that brings out shadows and subtext from the story it’s telling. It’s a world built out of the dark places in the woods of the Brothers Grimm, as though a city had been built over them but had inherited the dangers in dark places.

Thanks to the phantasmagoric animation style the disturbing story of an overlooked child becomes more than simply hard-edged realism, almost a kind of mythopoeic night terror. The images are shadowy, primarily dark smoky greys, and the figures constantly metamorphose from one thing into another like clouds or dreams. There’s a childlike feel to them, mostly, and specifically the feel of a child’s nightmare. The film is claustrophobic, in that it has a sense of closeness and of incipient disaster, but it’s claustrophobic with the weird euphoria of oxygen deprivation. This is a world always shifting from one thing to another, a hallucinatory reality that brings out shadows and subtext from the story it’s telling. It’s a world built out of the dark places in the woods of the Brothers Grimm, as though a city had been built over them but had inherited the dangers in dark places.

The Ottawa-based Barnhart links the story to other horrific crimes involving missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, which a recent Canadian government inquiry described as part of a larger genocide against Indigenous people. The word ‘genocide’ was used in the report in part because genocide must be understood as potentially deriving from omission — from failures to act, from overlooking wrongs. “Girl In the Hallway” dramatises the way in which the modern world makes it easy to overlook certain people, to not care about them, to not look out for them; and how in this atmosphere of neglect terrible things may happen. Barnhart’s film points out that the people we are encouraged to overlook tend to be those marginalised or outside of power groups, in terms (for example) of gender or ethnicity or age. That was the case of Xiana Fairchild. DeWolf’s story is powerful because he examines his own conduct without flinching, describing where at some points he failed and where at other points his responses were well-meaning but insufficient or misdirected. The animation brings out the power of his words specifically by its childlike feel: by presenting a world as someone like Fairchild might have understood it or not understood it, a place of nightmare and darkness where nothing is certain or comprehensible, where it is hard to find something or someone to trust.

After the showcase, four of the directors came out to take questions: Michelle Garza Cervera, Valerie Barnhart, Yfke Van Berckelaer, and Erica Scoggins. According to my (handwritten, possibly unreliable) notes they were first asked why they made the films they did, and what drew them to that particular story. Barnhart spoke about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls inquiry, and linked it to things she saw in her own community, and how indifference perpetuates genocide. Van Berckelaer said that her film was partly inspired by the MeToo movement and how it’s sometimes not easy to say no in a given situation. Garza Cervera said her film was made for film school, and while she did not write the script she picked it because she liked the theme of dark decisions. Scoggins said that she grew up hearing about the Boogeyman and wondering about the Boogeywoman. She said she thought male violence tended to be predictable, whereas women were feared for unpredictability and agency; she situated her story in horror to point up the absurdity of these social ideas — if you’re afraid of menstrual blood then the film’s horror, she said, and if not, then not.

The directors were then asked about their best and worst experiences in making their movies. Barnhart said the worst was trying to learn to animate. A visual artist, Barnhart taught herself animation to make the movie, and had a budget of $1000 Canadian. In a way, she said, this was probably good for a filmmaker, now she had been “forged in fire and despair.” Garza Cervera spoke about coming from Mexico and finding a good structured process in England. Scoggins talked about becoming close to her actors, and how one of them became a big brother to the rest of the cast, and sadly died a year later. Van Berckelaer said that the worst thing for her was asking people to work for free, while the best was seeing the actors work, especially respecting Derek De Lint, whose face never appeared on screen.

The directors were then asked about their best and worst experiences in making their movies. Barnhart said the worst was trying to learn to animate. A visual artist, Barnhart taught herself animation to make the movie, and had a budget of $1000 Canadian. In a way, she said, this was probably good for a filmmaker, now she had been “forged in fire and despair.” Garza Cervera spoke about coming from Mexico and finding a good structured process in England. Scoggins talked about becoming close to her actors, and how one of them became a big brother to the rest of the cast, and sadly died a year later. Van Berckelaer said that the worst thing for her was asking people to work for free, while the best was seeing the actors work, especially respecting Derek De Lint, whose face never appeared on screen.

Asked what was next, Barnhart said she wanted to do a comedy as a palate cleanser. Asked if their films were meant as proofs of concept for longer works, Van Berckelaer joked that she planned a slow push-in for an hour an a half. Scoggins said her film was definitely meant to lead to a feature, and that she’d finished a script and had had some meetings on the subject. Garza Cervera spoke about keeping her film short, and going to Mexico to work on a feature.

To another question, Van Berckelaer spoke about writing her film for her lead, and how she’d heard similar stories about auditions from women. Barnhart was asked about the process of making her film, which she said in part derived from ignorance about animation; after making 30 seconds she realised she’d chosen the most unforgiving form of animation possible. She said her budget limited her creativity, but creativity can find a way nevertheless. So with no money and no support, she still made a movie with a library card and an internet connection. Garze Cervera was asked why she made her movie in black-and-white, and she said it spoke to a sense of timelessness she wanted to bring to the setting. Barhart was asked how she found the narration for her film, and she said she found it on YouTube, and was a fan of DeWolf’s.

The directors were asked who in film they looked up to; Van Berckelaer said Guillermo Del Toro, Garza Cervera named a director whose name I was not able to catch, Scoggins said Lynch, and Barnhart thought for a moment before suggesting her mother; she said she had no answer to the question. Asked what the process of finding people for her film was like, Scoggins spoke about finding her lead in a coffee shop in Tennessee, and how she developed by leaps and bounds during filming. Her other actors were from theatre, she said, and also had never done film. As Scoggins had mentioned that her community was religious, she was asked if she’d had any objections to the finished work from family or friends. She said she had a strategy of telling people about the film without using red-flag words. She noted that her mother was impressed about boys in the film learning about periods, and so was open to the film. Generally Scoggins said there was more openness to the film in her community than she’d expected, and that she wants to challenge her mom even more.

The directors were asked who in film they looked up to; Van Berckelaer said Guillermo Del Toro, Garza Cervera named a director whose name I was not able to catch, Scoggins said Lynch, and Barnhart thought for a moment before suggesting her mother; she said she had no answer to the question. Asked what the process of finding people for her film was like, Scoggins spoke about finding her lead in a coffee shop in Tennessee, and how she developed by leaps and bounds during filming. Her other actors were from theatre, she said, and also had never done film. As Scoggins had mentioned that her community was religious, she was asked if she’d had any objections to the finished work from family or friends. She said she had a strategy of telling people about the film without using red-flag words. She noted that her mother was impressed about boys in the film learning about periods, and so was open to the film. Generally Scoggins said there was more openness to the film in her community than she’d expected, and that she wants to challenge her mom even more.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.