Fantasia 2019, Day 9, Part 1: It Comes

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

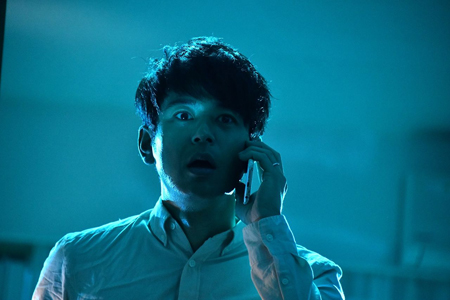

After a mysterious intro, the film starts with Hideki (Satoshi Tsumabuki) and Kana (Haru Kuroki), an apparently perfect young couple. Various bits of supernatural foreshadowing lead to the birth of their baby girl, Chisa, and Hideki throws himself into becoming the perfect father. But forces from his past are gathering, targeting Chisa. A friend, a professor of folklore named Tsuga (Munetaka Aoki, the Rurouni Kenshin movies) brings him to a disreputable writer, Nozaki (Jun’ichi Okada, Library Wars), and his spirit-medium girlfriend Makoto (Nana Komatsu, Jojo’s Bizarre Adventures). But will even they be enough to stop the evil coming for Hideki and Chisa?

This all just hints at the complexities of the plot, best experienced unspoiled. It Comes is an incredibly well-structured and well-paced movie that builds through a good collection of horror set-pieces and quieter character-driven moments to a stunning large-scale climax boasting one of the most fascinating examples of religious syncretism I’ve seen on film. At the very end, it has one of the most charming visual moments I’ve ever seen to indicate that the supernatural’s been thoroughly dealt with.

It is important that it be so well-crafted, I think, because as it builds it goes to some very strange places. The colours are lurid, slowly growing more so. And the film does not hesitate to increasingly explore genre as the film goes on, as well; Hideki and Kana are more-or-less real people when we meet them, and then Tsuga is a perhaps little more than real, and then Nozkaki and Makoto more than that, and then when we meet Makoto’s sister Kotoko we meet a character on another level of genre reality. And yet the tones work. The operatic feel of the high genre strangeness is fused to the everdayness of the young parents. And the story of the baby facing possession is given a weird grandeur by the surreal witchery that must be enlisted to fight the bogeyman threatening the child.

Underneath all that is a strong flashback-based structure that adds depth and new dimensions to things and people we think we know, without contradicting anything we’ve already seen. It is remarkably clever, playing with our emotions and sympathies in unexpected ways. This could have been gimmicky, but Nakashima and his actors keep it credible and at the same time comprehensible. Just the right amount of time is given to each twist, anchoring it to what came before without hammering home how it relates to everything else. Instead we get a sense of depth and complexity to the characters.

Underneath all that is a strong flashback-based structure that adds depth and new dimensions to things and people we think we know, without contradicting anything we’ve already seen. It is remarkably clever, playing with our emotions and sympathies in unexpected ways. This could have been gimmicky, but Nakashima and his actors keep it credible and at the same time comprehensible. Just the right amount of time is given to each twist, anchoring it to what came before without hammering home how it relates to everything else. Instead we get a sense of depth and complexity to the characters.

That helps the story say something about family and what makes a real family. The cast as a whole is strong here, as well, as each of them has a strong grasp on the precise register they have to play in the overall story. Together they tell a story about the nature of family groups; more specifically, about appearances and what makes a family a real family. The pressure of the horror brings out flaws in some characters and heroism in others. By the end the family we start with has been reconfigured into something healthier and more stable if perhaps slightly less conventional. It’s an oddly heartwarming conclusion for a horror film.

And this is emphatically a horror film. It’s Nakashima’s first horror movie, but there’s a full-throated love for the genre on display here. A strong sense of timing and craft, as well, yet it’s the ability to use the energy of genre structures and genre approaches that stands out. The further the movie explores the supernatural the more it allows characters to be flat in a genre fashion: the more their backstories have to do with plot beyond the immediate story. And it works, because it broadens the world, and because Nakashima knows where to position the story among these flatter characters. The story takes on just the right shape.

Whether it fits in with the subgenre of J-horror is inevitably going to be up to the individual. It strikes me that it does in the way it uses supernatural horror, psychological twists, plot reversals, and aspects of folk religion. It does something different, perhaps, in the way it brings in a much bigger and more explosive climax than a lot of J-horror. What is key, though, is that the horror comes at structurally significant moments of the film, and drives character and character choices. It’s not something that brings out theme or character so much as what theme and character are built of; not an element of the story, but the story itself.

Whether it fits in with the subgenre of J-horror is inevitably going to be up to the individual. It strikes me that it does in the way it uses supernatural horror, psychological twists, plot reversals, and aspects of folk religion. It does something different, perhaps, in the way it brings in a much bigger and more explosive climax than a lot of J-horror. What is key, though, is that the horror comes at structurally significant moments of the film, and drives character and character choices. It’s not something that brings out theme or character so much as what theme and character are built of; not an element of the story, but the story itself.

It may be least like the other Japanese horror films I’ve seen in the bright colours it uses, at least on occasion. This movie’s always fun to look at. It starts, in this as in so much else, in a relatively realistic register and then moves beyond that to a weirder, more riotous reality. It’s tempting to talk about it as a chaos or a delirium, but I think it’s more carefully judged. It’s visual craft of the best kind: craft that doesn’t feel like craft, encouraging direct sensory and emotional responses that pull the audience further into the story.

It Comes strikes me as a great success. It’s intelligent in structure and tells its story well; it has something to say, and says it by using genre conventions to powerful effect. The stylised reality may be off-putting to some. Frankly, I feel bad for those viewers. This was one of the most purely enjoyable movies I saw at Fantasia this year, and I say that as somebody who’s not a particular fan of horror movies.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.