Fantasia 2019, Day 4, Part 5: Shadow

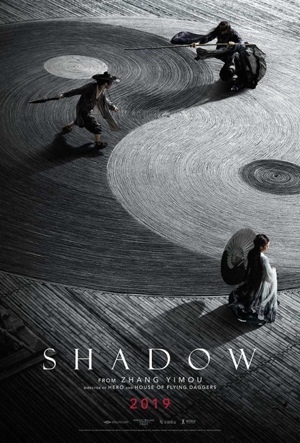

My fifth and last movie of July 14 brought me back to the Hall Theatre. I had not seen two consecutive movies that day in the same cinema; no two films had come from the same country. It was in retrospect a good day at Fantasia, and it was ending with a bang: the latest film from Zhang Yimou, Shadow (also known as Ying, 影). Written by Zhang with Li Wei, it’s a tale of historical battles and political machinations told with visual dynamism and a distinct colour sense, fitting nicely alongside previous works by Zhang such as Hero, House of Flying Daggers, and Curse of the Golden Flower.

My fifth and last movie of July 14 brought me back to the Hall Theatre. I had not seen two consecutive movies that day in the same cinema; no two films had come from the same country. It was in retrospect a good day at Fantasia, and it was ending with a bang: the latest film from Zhang Yimou, Shadow (also known as Ying, 影). Written by Zhang with Li Wei, it’s a tale of historical battles and political machinations told with visual dynamism and a distinct colour sense, fitting nicely alongside previous works by Zhang such as Hero, House of Flying Daggers, and Curse of the Golden Flower.

(The movie was preceded by an animated short, “Modern Babel,” written, directed, and animated by Lin Zhao. It follows a woman on an increasingly hallucinatory shopping expedition, as she must struggle against crowds and sinister black birds, while she and the rest of the world descend into violence and madness. It is expressionistic and indeed nightmarish, the design sense a little like Peter Kuper’s comics. It’s black-and-white, and does effectively create an oppressive visual atmosphere. I found it a bit bare, or perhaps a bit elliptical, in terms of story.)

Shadow opens with exposition. Long ago, in the 3rd century AD, two countries in what is now China battled for control of a city. The country of Pei lost when its general Ziyu (Deng Chao) was defeated in a duel with the unbeatable general Yang Cang (Hu Jun) of the kingdom of Yang. The king of Pei (Zheng Kai) is therefore annoyed to learn, as the movie opens, that Ziyu’s challenged Yang Cang to a rematch; the king has his own schemes to recover the city, which involve marrying off his sister (Guan Xiaotong). But all is not what it seems. The man everyone knows as Ziyu is in fact a double; the real Ziyu, gravely wounded by Yang Cang, has hidden himself away, operating through this double — his shadow, a man named Jingzhou. But has Ziyu’s wife Xiao Ai (Sun Li) developed a new kind of technique that will give Pei victory in battle?

This is a complex story, with various subsidiary characters contributing to the machinations. But it always remains clear, building almost mathematically to an explosive set of final battles. There is an operatic feel to the film, in its grandeur, its self-conscious seriousness, and, inevitably, its body count and tragedy. It’s a tone familiar from Zhang’s previous work, and so this feels a logical extension.

It strikes me as perhaps less grand in scope, but that may be a bit of an illusion. If Hero or House of Flying Daggers were notable for their colour work, Shadow is notable for the absence of colour. It attempts to echo Chinese ink painting, and does so by keeping to a largely black-and-white palette. Things — clothes, architecture, weaponry — have no colour to them, or very little. Only aspects of nature have some chromaticism: bamboo, leaves, flame, human flesh, human blood.

It strikes me as perhaps less grand in scope, but that may be a bit of an illusion. If Hero or House of Flying Daggers were notable for their colour work, Shadow is notable for the absence of colour. It attempts to echo Chinese ink painting, and does so by keeping to a largely black-and-white palette. Things — clothes, architecture, weaponry — have no colour to them, or very little. Only aspects of nature have some chromaticism: bamboo, leaves, flame, human flesh, human blood.

This has the effect of emphasising the moral greyness of the film, and indeed the greyness of war. The battles, when they come, are visually exciting and yet take part in rain and mud; there is implausible and extravagant combat choreography and yet also a weird grimness hanging over the scene. It’s a peculiar and complex mix of tones. That richness is the point, according to Zhang in this interview:

Actually for many years I’ve always liked the idea of making a film that presents or resembles this ink brush painting style. And finally I found a story that I believe is perfect for this artistic style. Because this story is about human nature. And human nature is not either black or white, there are different shades to it. It’s very rich. Just like the Chinese painting style: different shades of black, different shades of white. I think it’s perfect for this story.

Generally this feels a very water-oriented movie. The palace of the king of Pei is on a river. There is always mist or rain. A key plot point involves the water rising in the town where the final battle takes place. This makes the echo of ink painting more visible. It would also seem to have to do with the quality of yin, which is associated with water, the feminine, and shadow. As a contrast, the enemies of Yang are in fact linked to the masculine quality of yang; the unbeatable warrior Yang Cang is said to have embodied yang in his unstoppable spear. The solution, suggested by Xiao Ai, is a weapon based on the umbrella — again, water and yin to counter yang.

I am by no means deeply versed in the philosophy of yin and yang, but the film does make some of the basic concepts clear enough to see how the thematic outlines inform the film. What perplexes me is why a movie that seems to have so much to do with yin, the feminine, has so few actual women in it. There are two prominent women, who do help shape the plot (and one of whom opens and ends the film, which is in a sense circular), but overall the movie feels more oriented to the masculine characters.

I am by no means deeply versed in the philosophy of yin and yang, but the film does make some of the basic concepts clear enough to see how the thematic outlines inform the film. What perplexes me is why a movie that seems to have so much to do with yin, the feminine, has so few actual women in it. There are two prominent women, who do help shape the plot (and one of whom opens and ends the film, which is in a sense circular), but overall the movie feels more oriented to the masculine characters.

Then again, the violence and swordplay are held back until the end. This is nominally a wuxia film, but with few setpieces in its first two-thirds or so beyond the occasional practice duel. Surprisingly, there’s a remarkable sequence of instrumental passion on a zither, which, like the conscious references to ink painting and calligraphy, evoke traditional culture. Worth noting as well that the characters are based on characters in Romance of the Three Kingdoms, though from what I can tell this is far from a literal (or even partial) adaptation.

What does it all add up to? Is this a visual poem? An action movie? A meditation on Chinese philosophy? Of course Shadow is all of these things by turns, but in the end what’s it about? There’s a game-like sense to the film, characters always planning a move ahead of each other. So what’s the film itself playing at? If, as Zhang said, it’s about human nature, what is it illustrating? Perhaps in some ways it’s a contrast with the idea of pure black and white: the richness of grey makes up the world, as people of different kinds come together and intersect. Out of their interactions come kingdoms and wars, and, sometimes, marriages. And sometimes art. Thus this film, old and new, black and white, stark and rich, exciting and meditative. It’s worth watching, and worth pondering.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I watched this last night and it’s a very, very slow burn, but visually unlike anything I’ve ever seen before.

I cannot wait to see SHADOW!!!