Fantasia, Day 4, Part 4: Mystery of the Night

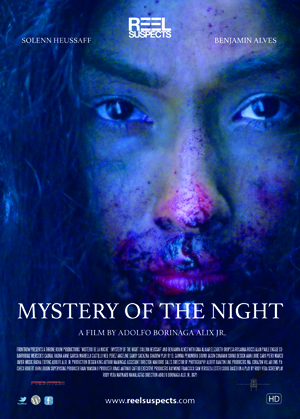

My fourth film of July 14 brought me back across the street to the De Sève Theatre for a tale from the Philippines, Mystery of the Night. Directed by Adolfo Alix Junior, it’s an adaptation of a play by Rody Vera called Ang Unang Aswang (The First Aswang). As written for the screen by Maynard Manansala, it’s a meditative story that doesn’t betray its stage origins in the slightest, a deliberately-paced visual spectacle about colonialism, magic, and the wilderness.

My fourth film of July 14 brought me back across the street to the De Sève Theatre for a tale from the Philippines, Mystery of the Night. Directed by Adolfo Alix Junior, it’s an adaptation of a play by Rody Vera called Ang Unang Aswang (The First Aswang). As written for the screen by Maynard Manansala, it’s a meditative story that doesn’t betray its stage origins in the slightest, a deliberately-paced visual spectacle about colonialism, magic, and the wilderness.

After an introduction told in the form of a shadowplay, the film proper begins in the 19th century, when Spain ruled the Philippines. There is a sin and an attempt to cover up that sin; we see these things, but the main dramatic action of the film takes place years later. The victim’s daughter (Solenn Heussaff) has been raised by forest spirits in the jungle. Grown to an adult who knows no human language, she meets Domingo (Benjamin Alves), the son of one of the men responsible for the cover-up; he, trespassing into the domain of the spirits, names her Maria. What happens between them, and the transformation she undergoes near the end to bring justice, forms the main part of the movie.

It’s difficult to summarise the film because the movement of the plot is relatively simple, but for that reason deserves to be experienced relatively unspoiled. There is a stately rhythm to events, which unfold simply, one thing leading to another with dreadful inevitability. This is by no means a plot-oriented movie, but I’m not sure it would be precisely accurate to call it centred on character, either. It’s driven perhaps by theme and visual sense as much as anything, and if that sounds unpromising, in practice I think it works surprisingly well.

The themes are deep and interconnected, if perhaps schematic. The original sin that drives the story is brought about and covered up by the collusion of the colonial church and the colonial state, male structures acting against a low-status woman. Powerful men from a built-up city make an incursion into the wilderness, and despite their best efforts, indeed ironically because of them, create a kind of innocent yet powerful female force within the wild forest. That woman, Maria, ends up being given her name by Domingo, and both of those names are symbolic; his choice for her says something about his character but is perhaps best understood as irony. In any event Maria herself is a creature without language — specifically, perhaps, without the language of colonial oppression. If their initial encounter is Edenic, in civilisation Domingo reveals himself to have a patriarchal attitude, using things and people for his convenience. This leads to Maria’s transformation, and violence that resolves itself with certain myths having reasserted their powers and certain other mythologies exposed as powerless.

The movie’s directly post-colonial, then, but it’s saved from being schematic by its power as cinema. The movie’s built on long takes and is sparing in dialogue; strange things happen, fantastical or horrific or mythic depending on perspective, but the film presents it all as of a piece with more conventional reality. You could call it magical realism, I suppose, and certainly there’s an undercutting of traditional mimetic realism at the same time as Alix directs his camera with an unsparing vision that seems to challenge everyone and everything we see. Much of the film happens, unsurprisingly, at night; and there is both a clarity and a shadowy feel to it. The sense of things happening beyond rational daylight is strong.

The movie’s directly post-colonial, then, but it’s saved from being schematic by its power as cinema. The movie’s built on long takes and is sparing in dialogue; strange things happen, fantastical or horrific or mythic depending on perspective, but the film presents it all as of a piece with more conventional reality. You could call it magical realism, I suppose, and certainly there’s an undercutting of traditional mimetic realism at the same time as Alix directs his camera with an unsparing vision that seems to challenge everyone and everything we see. Much of the film happens, unsurprisingly, at night; and there is both a clarity and a shadowy feel to it. The sense of things happening beyond rational daylight is strong.

There is I find a very specific experience given by films that take this kind of formal approach, de-emphasising dialogue as a driver of story in place of silent visual storytelling. They become dreamlike, and in my experience less bound to a sense of time. In this particular case a sense of dread also emerges, if only because we see great cruelty in the opening minutes. The mix of cultures in this time and place is not working peacefully, and the colonial experience is fundamentally one of injustice. But the story that unfolds is a kind of visionary rewriting of colonialism, one that is maybe less concerned with the occupying power and more interested in the conflict within the colonised: those who adopt to external ideologies and power structures opposed to those who can gain power from indigenous traditions of place.

That transformation at the end’s interesting because it involves pain and horror as well as power. It’s important, but frightful. This is not a movie that shies away from gore, and that is what we get here. (It may in fact strike audiences unfamiliar with this specific myth as bizarre; but that may be what makes it most effective, that it is local and specific.) While not a conventional horror movie, the film does use some horror tropes — the dark forest, the thick night, the clash of ‘civilisation’ and the wild — in a way that gives it a kind of narrative energy, even a genre kick.

That transformation at the end’s interesting because it involves pain and horror as well as power. It’s important, but frightful. This is not a movie that shies away from gore, and that is what we get here. (It may in fact strike audiences unfamiliar with this specific myth as bizarre; but that may be what makes it most effective, that it is local and specific.) While not a conventional horror movie, the film does use some horror tropes — the dark forest, the thick night, the clash of ‘civilisation’ and the wild — in a way that gives it a kind of narrative energy, even a genre kick.

It is important in saying all this not to forget about the actors, particularly the two leads, who create characters one can identify with. If the movie escapes being a run-through of thematic ideas, it’s partly because they bring life to the script. Particular notice has to be taken of the artistic and literal daring of Heussaff, not only crafting a character who is entirely open emotionally, but also often nude while on location in the jungle.

“The forest has its own logic,” we’re told at one point. Mystery of the Night can be seen as an exploration of that one line. Characters are haunted by what they find in the forest, are warped by it, in the case of Maria are wholly shaped by it. And implicitly this logic is different from the world outside the forest, the human world of laws and patriarchy. The thematic approach and structure is clear, and if it doesn’t challenge those themes, it doesn’t really need to because the themes become the framework for an excellent technical and artistic piece of storytelling. The movie’s often beautiful, composed and still, while also being full of life when needed. It’s a fable told with conscious art using genre techniques and transgression to bring alive a vision of history and the forces underlying history. It’s fine work.

After the film, Adolfo Alix Junior, Solenn Heussaff, and Benjamin Alves came out to take questions (I did my best to takes notes of their answers, but as always, I cannot guarantee accuracy). Asked first about portraying her character’s emotions and perhaps getting at a kind of sadness, Heussaff spoke about trying to portray sadness and anger without words or sound. Alves spoke about finding parallels to the action in real life and translating it to the character, noting a lot of it was in the script. One picks and chooses the layers of the character to come across, anger and guilt and regret. The set was light, in part because every day involved filming emotionally heavy material. Given the style of the film, what a character went through in a scene always had to be visible, as there were few close-ups. Because of the long takes, if the actors didn’t nail a scene they’d have to do the whole thing over.

After the film, Adolfo Alix Junior, Solenn Heussaff, and Benjamin Alves came out to take questions (I did my best to takes notes of their answers, but as always, I cannot guarantee accuracy). Asked first about portraying her character’s emotions and perhaps getting at a kind of sadness, Heussaff spoke about trying to portray sadness and anger without words or sound. Alves spoke about finding parallels to the action in real life and translating it to the character, noting a lot of it was in the script. One picks and chooses the layers of the character to come across, anger and guilt and regret. The set was light, in part because every day involved filming emotionally heavy material. Given the style of the film, what a character went through in a scene always had to be visible, as there were few close-ups. Because of the long takes, if the actors didn’t nail a scene they’d have to do the whole thing over.

Asked about his background with the folklore of the Aswang, Alix said he was introduced to stories of the creature in his youth. When he read the play he had the idea of putting it on film. He observed that the situation in the Philippines was very surreal, struggling with the Spanish heritage and forging their own identity; which he related to the Aswang, born out of pain. Asked if he had a background in theater, Alix said no, though the film was based on a play; he did specifically want to do the opening and closing of the film as a shadowplay, emulating a tradition of stories told as shadowplays against blankets.

Asked about the soundtrack, which used a certain kind of chanting, Alix said it was based on ritual chanting of priestesses who call spirits. They worked extensively with one, and tried to capture the emotions her chants evoked. Asked about the shot selection, which seemed to keep characters at arm’s length, Alix said that as a filmmaker he wants to be an observer. TV, as a counter-example, brings one in too close to a character and dictates the emotion a viewer should feel. He preferred to do long takes, earning a close-up at the end of the film so that one can feel all the pain involved in that moment.

Asked about the process of acting, Alix said he wanted the actors to physicalise the emotions, difficult in the wilderness location. Alves (per my notes) observed that it was “cold as fuck.” Heussaff spoke about trying to find the reality of what’s happening, anchoring a fantastic milieu in the real. It is difficult, she said, for an actor to ground a scene in what they feel when they must do it over and over again. She spoke about one scene in particular she loved, when her character leads Domingo to a specific part of the forest, bringing him into her universe. By contrast, she thought the horror was primarily created by atmosphere, generated by emotions.

Asked about the process of acting, Alix said he wanted the actors to physicalise the emotions, difficult in the wilderness location. Alves (per my notes) observed that it was “cold as fuck.” Heussaff spoke about trying to find the reality of what’s happening, anchoring a fantastic milieu in the real. It is difficult, she said, for an actor to ground a scene in what they feel when they must do it over and over again. She spoke about one scene in particular she loved, when her character leads Domingo to a specific part of the forest, bringing him into her universe. By contrast, she thought the horror was primarily created by atmosphere, generated by emotions.

Asked about the choice to portray the spirits of the forest clothed while humans were often nude, Alix said it was a decision based on their research, and based the designs off a culture in the north of the Philippines not colonised by the Spanish. Maria was nude to help set up the final choice she made, visually and practically, and also to help show her emotions physically as they could not be expressed verbally. Further, as the character is not of the culture from which they’d drawn the spirit clothes, they felt it would have been disrespectful to dress her in that culture’s clothes.

Asked about the contrast of city and forest, Alix said that as a director he was drawn to story but did consider those themes, and how putting images together drew out meaning. To that extent a contrast was deliberate. He spoke about kids going to the forest and creating things out of their imagination; Alves spoke about his first scene in the forest with Maria being a interaction about primal needs. Asked whether it was difficult to make this film in a Catholic country, Alix said the film had yet to be released in the Philippines, and he looked forward to the reaction. He hoped it would provoke a healthy discussion over the sort of things that had happened in the country and really were part of history. Alves observed that both he and Heussaff were known for more wholesome roles in the Philippines, so this film really broke new ground for both of them — and they were honoured to debut it at Fantasia.

Asked about the contrast of city and forest, Alix said that as a director he was drawn to story but did consider those themes, and how putting images together drew out meaning. To that extent a contrast was deliberate. He spoke about kids going to the forest and creating things out of their imagination; Alves spoke about his first scene in the forest with Maria being a interaction about primal needs. Asked whether it was difficult to make this film in a Catholic country, Alix said the film had yet to be released in the Philippines, and he looked forward to the reaction. He hoped it would provoke a healthy discussion over the sort of things that had happened in the country and really were part of history. Alves observed that both he and Heussaff were known for more wholesome roles in the Philippines, so this film really broke new ground for both of them — and they were honoured to debut it at Fantasia.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Ah yes, the “more wholesome roles”. I’m sure it says something about contemporary society that this movie, which is (among other things) a morality tale, can fall into the realm of “unwholesome” merely because of some of its warranted stylistic choices. “Patriarchal mores, something something”.

Hope I can see this someday. Good work, Matthew.