Fantasia, Day 4, Part 1: The Wonderland

In reviewing the movies I see at Fantasia I like to mention the theatre in which I see a film, because the room the film’s screened in often gives a hint about the movie’s nature. The smaller De Sève is often a venue for indie cinema and lesser-known pictures. The larger Hall will usually hold more obviously popular movies, meaning a lot of action films and blockbusters. This is not inevitable, and there are a number of reasons why something you’d think you’d see in one cinema gets hosted in the other. But the two theatres do have their own personalities, and sometimes you watch a movie that fits the personality of the place perfectly.

In reviewing the movies I see at Fantasia I like to mention the theatre in which I see a film, because the room the film’s screened in often gives a hint about the movie’s nature. The smaller De Sève is often a venue for indie cinema and lesser-known pictures. The larger Hall will usually hold more obviously popular movies, meaning a lot of action films and blockbusters. This is not inevitable, and there are a number of reasons why something you’d think you’d see in one cinema gets hosted in the other. But the two theatres do have their own personalities, and sometimes you watch a movie that fits the personality of the place perfectly.

Which is all by way of saying that on Sunday, July 14, I headed down to the Hall to watch The Wonderland (also Birthday Wonderland, originally Bāsudē wandārando, バースデー・ワンダーランド), a new animated film by Keiichi Hara, whose previous film Miss Hokusai had greatly impressed me. Miho Maruo, who wrote the script adapting Miss Hokusai from the original manga, also handles the script for The Wonderland, which is based on a 1988 novel (Chikashitsu Kara No Fushigi Na Tabi, literally Strange Journey From the Basement) by Sachiko Kashiwaba. Kashiwaba’s an award-winning children’s writer in Japan; Hayao Miyazaki once tried to adapt her novel Kirino Mukouno Fushigina Machi (A Mysterious Town Over the Mist), ultimately scrapping the attempt but keeping the bathhouse setting for the film that became Spirited Away. If The Wonderland is any indication, her work and themes have some clear parallels with his.

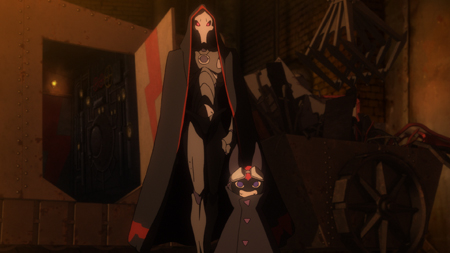

Akane (Mayu Matsuoka) is a Japanese girl about to turn 13, who goes to the knickknack shop operated by her flighty aunt Chii (Anne Watanabe) to get her birthday present. There, she and Chii are surprised when she encounters the mustachioed and top-hatted alchemist named Mister Hippocrates (Masachika Ichimura) and his assistant Pipo (Nao Tôyama), who reveal that Akane has a destiny in a mysterious otherworld that can only be reached through the basement of Chii’s store. It turns out that in this fantasyland Akane’s the latest incarnation of the Goddess of Green Wind, who is the only one who can save the world from its slow decay into colourlessness. Akane’s opposed by mysterious figures who have their own schemes to stop the erosion of colour, and sets out on a quest through the various lands of this World Beyond to the centre of all things.

This is a straight-ahead well-told fantasy adventure story. Designs are consistently strong and inventive; there’s a prodigality of visual ideas, with elaborate and individual interiors and exteriors. The motif of colour comes across well, as every location is filled with bright eye-popping hues except for those suffering under the entropic plague. Oddly, the real-world settings have almost as much colour to them, making the World Beyond perhaps a trifle less distinct than it might have been. Still, there’s no danger of confusing the two realms; not just the magic but the societies of the other world are different from this one. In that world, technology stopped developing after a certain point: “We were happy enough as we were, I suppose,” one of the inhabitants reflects.

In The Encyclopedia of Fantasy critic John Clute described a basic plot structure underlying a lot of fantasy, involving a thinning of the wonder of some magical land, a quest to restore the land, a recognition of what has to be done, and a metamorphosis leading to a healing of the land. All of that is present in The Wonderland, which ticks off the steps in perfect order. There’s no question of influence — apart from anything else, the source text was written years before The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. But there is a feeling of sameness, at least for an adult viewer; a cumulative lack of surprise. Sometimes the downside of a story being a perfect example of a genre piece is that it lacks a certain feeling of newness.

In The Encyclopedia of Fantasy critic John Clute described a basic plot structure underlying a lot of fantasy, involving a thinning of the wonder of some magical land, a quest to restore the land, a recognition of what has to be done, and a metamorphosis leading to a healing of the land. All of that is present in The Wonderland, which ticks off the steps in perfect order. There’s no question of influence — apart from anything else, the source text was written years before The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. But there is a feeling of sameness, at least for an adult viewer; a cumulative lack of surprise. Sometimes the downside of a story being a perfect example of a genre piece is that it lacks a certain feeling of newness.

Which is not to say there’s nothing of interest here beyond the visuals. The Wonderland does a good job of linking the fantasy plot of healing a magical land to contemporary environmental concerns. The villains are made distinct by not being the cause of the environmental degradation but powerful amoral figures with their own plans to fix things. And it’s nice to see a children’s story in which the helpful (and here engagingly genre-savvy) adult is really not that much help after all. (There’s also an interesting element in that we’re not told who from this world was the original Goddess; for a couple of reasons I suspect it might have been Akane’s mother, but that’s not hinted at in dialogue.)

I would say that other than the environmental themes, the movie feels a little lightweight. Of course, it’s possible that viewers closer to Akane’s age will get more out of it; implicitly this is a coming-of-age story, in which a girl who begins the film by ducking school comes to accept her power and responsibility in a larger world. In this sense there’s a good contrast in her story with what we learn about the main villain. Then again, it’s debatable how much these ideas come out at the end, which generally risks an anticlimax with an extended denouement that takes too much care in wrapping up loose ends.

I would say that other than the environmental themes, the movie feels a little lightweight. Of course, it’s possible that viewers closer to Akane’s age will get more out of it; implicitly this is a coming-of-age story, in which a girl who begins the film by ducking school comes to accept her power and responsibility in a larger world. In this sense there’s a good contrast in her story with what we learn about the main villain. Then again, it’s debatable how much these ideas come out at the end, which generally risks an anticlimax with an extended denouement that takes too much care in wrapping up loose ends.

Still, this movie feels like a competent enough cross between Miyazaki and The Wizard of Oz. Like Oz, a young woman from this world journeys through strange lands to reach a city at the centre of everything; there’s even a fairly specific parallel to the ruby slippers (or Silver Shoes). Like a lot of Miyazaki stories, there’s a young woman moving in a magical world in which forces who appear evil turn out simply to have reasonable agendas that have no room for compromise; and, if the girl does not get a flying scene, she does get a breathtaking underwater journey that gives much the same sense. Put all this together, and it’s difficult to feel you’re not getting your money’s worth from The Wonderland. But at the same time it’s difficult to point to anything truly new in what the film does. There is, ironically, a certain lack of wonder.

In the end, this is a movie that knows what it is and embraces it. It does exactly what it sets out to do. If as an adult I’m finding it very familiar, younger viewers who haven’t seen so many similar stories may well enjoy it more than I can. It is a very well-executed and quickly-paced example of this sort of tale, and it puts a lot of lushly-designed environments on the screen. I can’t say I was overwhelmed, but I was entertained. This was the perfect sort of movie to see at a noon screening in the Hall Theatre: a big, well-animated, and visually unpredictable fantasy-adventure cartoon.

In the end, this is a movie that knows what it is and embraces it. It does exactly what it sets out to do. If as an adult I’m finding it very familiar, younger viewers who haven’t seen so many similar stories may well enjoy it more than I can. It is a very well-executed and quickly-paced example of this sort of tale, and it puts a lot of lushly-designed environments on the screen. I can’t say I was overwhelmed, but I was entertained. This was the perfect sort of movie to see at a noon screening in the Hall Theatre: a big, well-animated, and visually unpredictable fantasy-adventure cartoon.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.