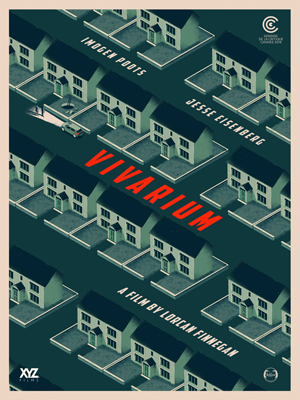

Fantasia 2019, Day 2, Part 3: Vivarium

I’d skipped the first day of the 2019 Fantasia Festival since the only movie I wanted to watch, The Deeper You Dig, played the next afternoon. That gave me three movies on Day 2, and after seeing first an indie horror film made by three people and then an Australian comedy led by a major Hollywood star, I could only wonder what I’d get in the Irish-Danish-Belgian co-production called Vivarium.

I’d skipped the first day of the 2019 Fantasia Festival since the only movie I wanted to watch, The Deeper You Dig, played the next afternoon. That gave me three movies on Day 2, and after seeing first an indie horror film made by three people and then an Australian comedy led by a major Hollywood star, I could only wonder what I’d get in the Irish-Danish-Belgian co-production called Vivarium.

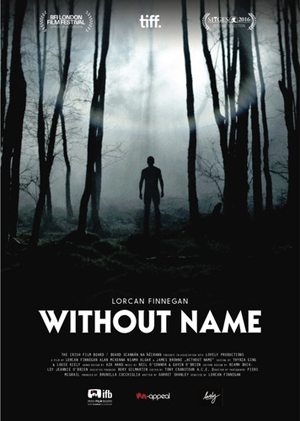

Directed by Lorcan Finnegan from a script by Garret Shanley, it was based on a story by Finnegan and Shanley (the same team collaborated on Finnegan’s previous film, Without Name). Imogen Poots and Jesse Eisenberg star as Gemma and Tom, a young childless married couple hoping to buy a home. A strange real estate salesman named Martin (Jonathan Aris) takes them to see a property in a new housing development. The place is eerily perfect and inhuman, the development empty of all other life. Then Martin vanishes, and when Tom and Gemma try to drive away they find geography doesn’t work right; they constantly find themselves back at the front door of the house Martin selected for them, number 9.

Whatever they do, they cannot escape. The streets are a maze that always returns them to the start. Their car eventually runs out of gas. And then a box is delivered, with a baby boy inside, and a note telling the couple that if they raise the child they’ll be allowed to leave. They do start to take care of the infant, but the boy grows quickly into an uncanny child (Senan Jennings) with inhuman reactions. What will he become as an adult? And what will it cost them to see it?

This is a visually striking movie that exploits the formal qualities of CGI and indeed of digital photography. Tom and Gemma are trapped in a world of unreal balloon-clouds; of perfect blue sky and of infinite green houses, their colours boosted just a little, just not quite real. The opening, introducing Gemma at the school where she teaches, is vital in providing a contrast — in showing what the real world looks like. More specifically, the opening shots of the movie show a cuckoo pushing eggs out of the nest it’s claimed; in addition to anticipating the film to come, these first shots are a vivid depiction of actual nature that establishes the sterility of the housing development as a stark opposition to the world of living things.

The trick to Vivarium, for me, was realising that it’s not a puzzle-box story with intricate rules that can be solved, a tale filled with clues that all resolve at the end. I found myself watching the story as if it were, probably because the attempts to escape early on led me to wonder a bunch of things beginning “but what if they tried —” or “OK, but how about if they —” and various other formulations that missed the point. In retrospect it’s clear that the reason for showing Tom and Gemma’s escape attempts was (at least in part) to establish that whatever they come up with, it wont work; we can imagine other plans, but they’d all be doomed to failure. I’m not sure whether my inability to grasp that at first viewing was my fault or whether the movie’s set up in a way that will encourage at least some viewers to take it as a purely logical game.

The trick to Vivarium, for me, was realising that it’s not a puzzle-box story with intricate rules that can be solved, a tale filled with clues that all resolve at the end. I found myself watching the story as if it were, probably because the attempts to escape early on led me to wonder a bunch of things beginning “but what if they tried —” or “OK, but how about if they —” and various other formulations that missed the point. In retrospect it’s clear that the reason for showing Tom and Gemma’s escape attempts was (at least in part) to establish that whatever they come up with, it wont work; we can imagine other plans, but they’d all be doomed to failure. I’m not sure whether my inability to grasp that at first viewing was my fault or whether the movie’s set up in a way that will encourage at least some viewers to take it as a purely logical game.

There is logic here, and ultimately a kind of explanation for events, but it’s not aiming at airtight rationality. This is a symbolic movie, about the way of life of the modern world. Gemma and Tom never worry about their old lives, for example, not that we see on screen; never worry about their jobs, their parents, or anything else. We can assume they do off-camera, of course. But the choice to keep those worries offscreen says something about what the movie wants to focus on and how it wants to build its characters.

There is a deliberate aridity to the film, and Poots and Eisenberg do a strong job of crafting performances that make Gemma and Tom feel like real living people. Eisenberg is especially strong, quiet and tragic, growing obsessed with digging a hole in the front yard of number 9 just because it’s something to do that seems like it might lead to a way out or to some kind of answer. It’s heartbreaking to see Tom spend all his time at this fruitless endeavour, and to see Gemma try to be supportive without really understanding what it is she’s supporting: “This is something I can do,” he snaps at her. “Please just let me do this.”

There is a deliberate aridity to the film, and Poots and Eisenberg do a strong job of crafting performances that make Gemma and Tom feel like real living people. Eisenberg is especially strong, quiet and tragic, growing obsessed with digging a hole in the front yard of number 9 just because it’s something to do that seems like it might lead to a way out or to some kind of answer. It’s heartbreaking to see Tom spend all his time at this fruitless endeavour, and to see Gemma try to be supportive without really understanding what it is she’s supporting: “This is something I can do,” he snaps at her. “Please just let me do this.”

Of course this is a parodic recapitulation of traditional gender roles, even as their situation in the unreal house with their unreal boy is a parody of family life. Vivarium succeeds because it’s recognisable, because it’s prepared to explore its set-up deeply, and because it has a fresh perspective on the things it’s talking about. It’s more than another film about the dehumanising blandness of the suburbs. It’s a subversive examination of the family unit under capitalism. It is a strong science-fictional satire of society, and does not shy away from the bleakness of its subject without at any point wallowing in that bleakness.

It has a few flaws. Some plot points are introduced that don’t really pay off; in particular a book written in a strange alphabet. While an overall explanation for events is given, a few aspects remain unclear or underdeveloped. And I can’t help but think that for all the likeability and craft Poots and Eisenberg bring, the script might have given their characters a bit more depth. It’s tricky to give characters in a story like this individuality without diminishing their nature as symbolic everypeople, but a bit more than what we got might have been useful.

It has a few flaws. Some plot points are introduced that don’t really pay off; in particular a book written in a strange alphabet. While an overall explanation for events is given, a few aspects remain unclear or underdeveloped. And I can’t help but think that for all the likeability and craft Poots and Eisenberg bring, the script might have given their characters a bit more depth. It’s tricky to give characters in a story like this individuality without diminishing their nature as symbolic everypeople, but a bit more than what we got might have been useful.

Still, this is cerebral science fiction with a surreal symbolic edge that largely works. The powerlessness of Gemma and Tom, caught in the titular vivarium, doesn’t overwhelm the film; they always think there’s some kind of way out. Gemma, a teacher, and Tom, a professional gardener, respond to pressure by becoming more of what they already are, in a way that aids the unseen puppet masters of their fate. Thus Vivarium is sad and human, and, ultimately, an effective parable.

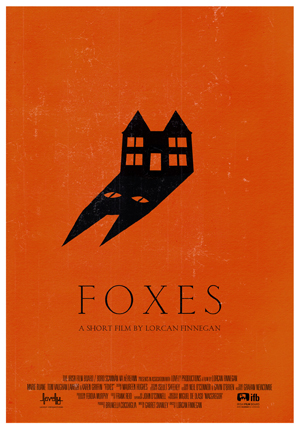

After the film director Lorcan Finnegan came out to take questions. Asked where the idea for the film came from, Finnegan said it started with a short film, and discussed the housing market in the Irish countryside where developers seeking profits built estates of clone houses, later abandoned. He made a short set in these houses about supernatural foxes representing nature reclaiming the land, but felt he had more themes he wanted to explore in that setting. At which point he saw a David Attenborough nature documentary about cuckoos.

Asked if he was exploring the theme that wanting things destroy us, he said yes, absolutely. From the time we’re young we’re presented with a set of ideas, including a “dream house;” here the idea’s literalised by making the housing development dreamy, with storybook-perfect clouds. An observation that Tom was digging his own grave in the film led Finnegan to note the digging was a parallel to work, but also to the process of paying a mortgage. At another observation, about the uncanny child disturbing Gemma and Tom by watching TV late at night in the way children disturb parents by becoming absorbed in media adults don’t understand, Finnegan reflected that he didn’t just have TV in mind but video games and the internet — the content children absorb that frightens their parents.

Asked whether the film was written with the actors in mind, Finnegan said no, not at all. The characters were different ages in different drafts, and a draft in which Gemma was a schoolteacher got to Poots’ agent and then to her; she liked it, and when she met with the creators they fell to talking for hours about various subjects and indeed forgot to talk about the film. It was Poots who suggested Eisenberg, with whom she had just worked on The Art of Self-Defense. She sent him the script, and he liked it.

Asked about the soundtrack, Finnegan mentioned that his first thought was not to have music, and rely on his sound designer (he noted that the designer worked with Lars von Trier, an example of the film drawing talent from three countries, which sometimes got a little tricky). And he spoke about creating a kind of sonic vacuum with no reverb, and how the soundscape of the film developed over months. Asked specifically about the sound effects when the child spoke, Finnegan mentioned it was the voice of the estate agent at the beginning of the film mixed with a boy pitch-shifted down; through the film this gradually shifted to become fully the adult voice.

Asked about the soundtrack, Finnegan mentioned that his first thought was not to have music, and rely on his sound designer (he noted that the designer worked with Lars von Trier, an example of the film drawing talent from three countries, which sometimes got a little tricky). And he spoke about creating a kind of sonic vacuum with no reverb, and how the soundscape of the film developed over months. Asked specifically about the sound effects when the child spoke, Finnegan mentioned it was the voice of the estate agent at the beginning of the film mixed with a boy pitch-shifted down; through the film this gradually shifted to become fully the adult voice.

Asked about the movie’s visual aesthetic, Finnegan said the architecture of the estate was based on actual ghost estates. They scanned a house with LIDAR and used it for a 3D test, then built scale replicas of three exteriors in a warehouse in Belgium. Green screens and digital mattes did much of the rest. They tried different colours for the houses until they hit on a certain shade of sickly green that affected the actors’ complexion.

Asked about a sequence at the end of the movie, Finnegan said it was meant to suggest neighbours, other inhabitants of the vivarium, at a kind of different quantum level, and thus to suggest the atomisation of society. Asked if his mother had seen the film, he said yes, and she thought it was great. She knew he was sick, he said, and anyway he blamed it all on the writer, who clearly had mother issues. Asked about the film’s version of suburbia, Finnegan said he wanted the horror to come from uniformity, citing photographers including Andreas Gursky; he wanted to reverse what should look nice and friendly.

Asked about other drafts, Finnegan said he had written more explanation into the film, but took it out to focus on existential dread, saying he thinks films tend to explain too much. He wanted a sense that you knew enough to get into the film quickly, citing a brief scene early on with Gemma and Tom singing in their car as a moment that should give audiences the sense they know these people. He noted that some of the explanations in earlier drafts didn’t survive because he knew he tends to remove explanations in editing anyway.

Asked specifically if he’d had more about the mysterious book, he said he had, and that the book represented a kind of lesson given to the boy by people with a different mindset. Finally, asked about the use of diagetic songs in the soundtrack, he said they had enough money for three tracks. He tried the film first with punk songs, but found it didn’t work; he didn’t want the characters to be too cool or anarchistic. He ended up with ska, which he felt was a nice contrast to the environment of the rest of the film.

That ended the questions, and ended the night for me. I’d be back the next morning for something more action-packed.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

“It’s a subversive examination of the family unit under capitalism.”?

All right, before I call H.U.A.C., I suppose I’ll wait for you to expand on that. As a foaming-at-the-mouth Capitalist American, I can’t say that I saw much, if anything, specific to “capitalism” any more than a system that could be described as German Liberal Democrat, Danish Socialism, or even Peronism.

Do you mean “capitalism” as short-hand for Western Modernity?

That’s about it, yeah. I mean, by a strict definition, even you guys down south don’t have ‘true’ capitalism, in that the government goes around building roads and running a post office and so forth. So, yeah, I’m using the broad definition of capitalist under which us social-democrat types count; basically in which a mixed economy is read as capitalist. That make sense?

Mornin’, Matt, and Happy Labour Day (for we south of the border types).

Yes, that covers it. Forgive the snap reaction but I’ve had awkward conversations about the term in the past, mostly with fellow (US of) Americans and what with the sometimes younger coterie I interact with, some “clarification” can be in order.

But thank you for responding. Obviously I’d never sic’ H.U.A.C. on you. (Reasons being I hold you in esteem, you’re Canadian, and the committee is, alas, disbanded.)

Cheers.