Germ Warfare, Sentient Planets, and Dark Age Alchemy: The Best of Murray Leinster

|

|

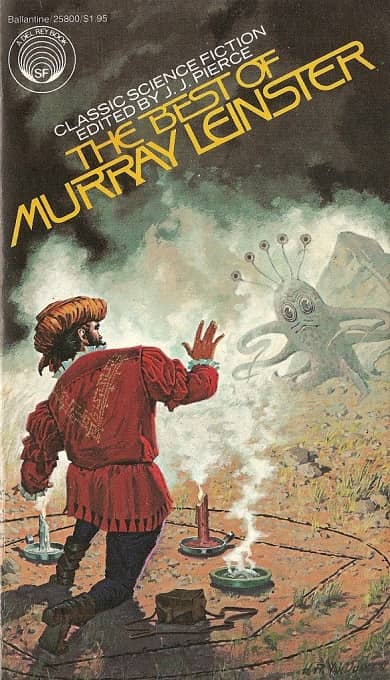

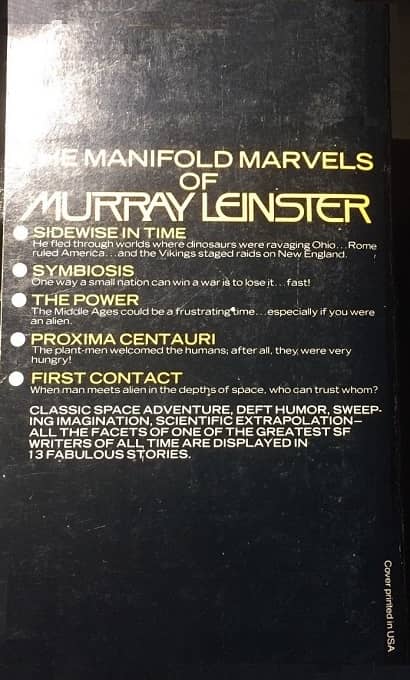

The Best of Murray Leinster (1978) was the fourteenth installment in Lester Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction Series. J. J. Pierce returns to give the introduction to this volume. H. R. Van Dongen (1920–2010) returns to do his fourth cover of the series, having done the cover for the seventh volume in honor of John W. Campbell, the tenth volume in honor of Fredric Brown, and the eleventh in honor of Jack Williamson. Since Leinster was already passed away in 1978, no afterword is included in this volume.

Murray Leinster (1896–1975) was the nom de plume of American writer William Fitzgerald Jenkins. Pierce refers to Leinster as ‘The Dean of Science Fiction”, clearly showing a deep respect for him, and I think also an indication of Leinster’s representativeness as an early and grand leader of pulp SF.

I’ve often heard early pulp SF described as basically following “engineer-solving” plots. I think I’ve understood what this meant, and I know I’ve seen examples of these in earlier volumes of the Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction Series. But Leinster is sort of a practitioner of this sort of plotting par excellence. What do I mean? Leinster’s plots tend to center upon some difficult problem that is presented as unsolvable (or nearly so), but by the end of the story the problem is usually solved in some sort of rational or scientific way. At first blush, this may sound fairly boring, and it has the potential to come off as overly preachy about the goodness of science. But in reading Leinster, you often get pulled into the problem of the story, and are sometimes surprised with how science answers or attempts to answer the issue at hand.

[Click the images for vintage-sized versions.]

In general, Leinster’s stories can be seen as thought experiments: imaginary ideas that are then logically teased out or naturally extended to see what costs or benefits might arise. Though science or scientific ingenuity is always presented as a good, Leinster is much more pessimistic about humanity’s use of science, and human greed or pride is often a problem that science alone seems unable to solve. Regardless of these issues, Leinster’s stories are intriguing reads.

For example, “Symbiosis” is a story that seeks to apply the principle of biological symbiotic mutualism to social human interaction. Scientists come to the fore by combining vaccination and germ warfare so that an invading army is powerless against it though the invaded people are immune. It’s an ingenious way of neutralizing a military force and Leinster suggests that this principle can somehow be extended to world peace, but how this is to be accomplished is left entirely unclear.

“The Lonely Planet” is also something of a thought experiment where a newly discovered planet is found to be a sentient creature, capable of learning and growing through its interactions with humans. Leinster presents its earliest human visitors as simply taking advantage of the new planetary entity while unknowingly giving impetus to unwanted later consequences. Leinster’s working out of this plot, over centuries, is incredible yet convincing.

In “Keyhole” a lunar alien is captured and observed in order to learn its species’ secrets so they can be conquered or enslaved for mining use on the moon. However, it turns out in the end that the alien has allowed itself to be captured and was actually studying the humans. Reminds me of the comic strip I saw one time of Pavlov’s dog, who says to another dog next to him, “Watch this. Every time I salivate, I make this guy write down things on his clipboard.” Haha!

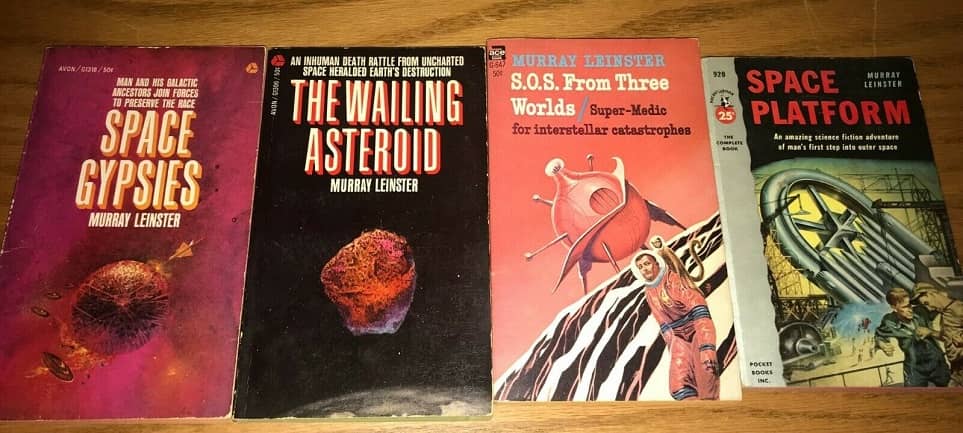

Vintage paperbacks by Murray Leinster

“The Power” is another interesting tale, and quite different from most of the Leinster stories in this volume. It’s supposedly a found medieval manuscript, translated from Latin, detailing a “dark-age” alchemist’s or wizard’s attempt to call up and control a demon. But from the modern reader’s perspective, it’s clear that the medieval wizard has actually come in contact with an alien who has become stranded on earth. The alien seeks to impart grand knowledge to the wizard, but unfortunately given the wizard’s ignorance, he attempts to “bind the demon” to extort it for magical secrets. The attempt leads tragically to the alien’s death, and humanity’s loss of superior scientific knowledge.

One of the interesting facets of these Del Rey Classic Science Fiction books is that the stories are presented in chronological order of publication. So this can sometimes show how an author’s style might change over time. Leinster’s characters tend to be flat. But the last story in this volume, “Critical Difference,” shows some real depth of emotion and characterization. The story takes place on a faraway planet, with a lone human research and mining station, where a solar event plunges the whole solar system into a critical ice age. Most of the story is foreboding and bleak where the known science seems unable to come up with a plan to save the humans from extinction. But Riki, a female character cries out at one point:

We humans are the only creatures in the universe who don’t do anything else [but change facts]! Every other creature accepts facts. It lives where it is born, and it feeds on the food that is there for it, and it dies when the facts of nature require it to. We humans don’t. Especially we women! We won’t let men do it, either! When we don’t like facts — mostly about ourselves — we change them. But important facts we disapprove of — we ask men to change for us. And they do! (p. 352)

Putting aside the sexism and melodramatic flare here, this point in the story represents a real change in Leinster’s characterizations from most of his earlier stories. The hope and emotion expressed here is actually very effective in the story, and impels the main character to seek harder after a scientific solution regardless of the available facts. One may see this as mere wishful thinking, but Leinster turns it into a fairly powerful moment that makes the reader want to cheer on the protagonist.

I had never read Murray Leinster before. And though this volume represents an older tradition of SF-storytelling, I think it’s a highly enjoyable collection and I greatly recommend it. I hope that the stories of Murray Leinster will not be forgotten.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents for The Best of Murray Leinster:

“The Dean of Science Fiction” by J. J. Pierce

“Sidewise in Time” (Astounding Stories, 1934)

“Proxima Centauri” (Astounding Stories, 1935)

“The Fourth-dimensional Demonstrator” (Astounding Stories, 1935)

“First Contact” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1945)

“The Ethical Equations” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1945)

“Pipeline to Pluto” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1945)

“The Power” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1945)

“A Logic Named Joe” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1946)

“Symbiosis” (Collier’s Magazine, 1947)

“The Strange Case of John Kingman” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1948)

“The Lonely Planet” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1949)

“Keyhole” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1951)

“Critical Difference” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1956)

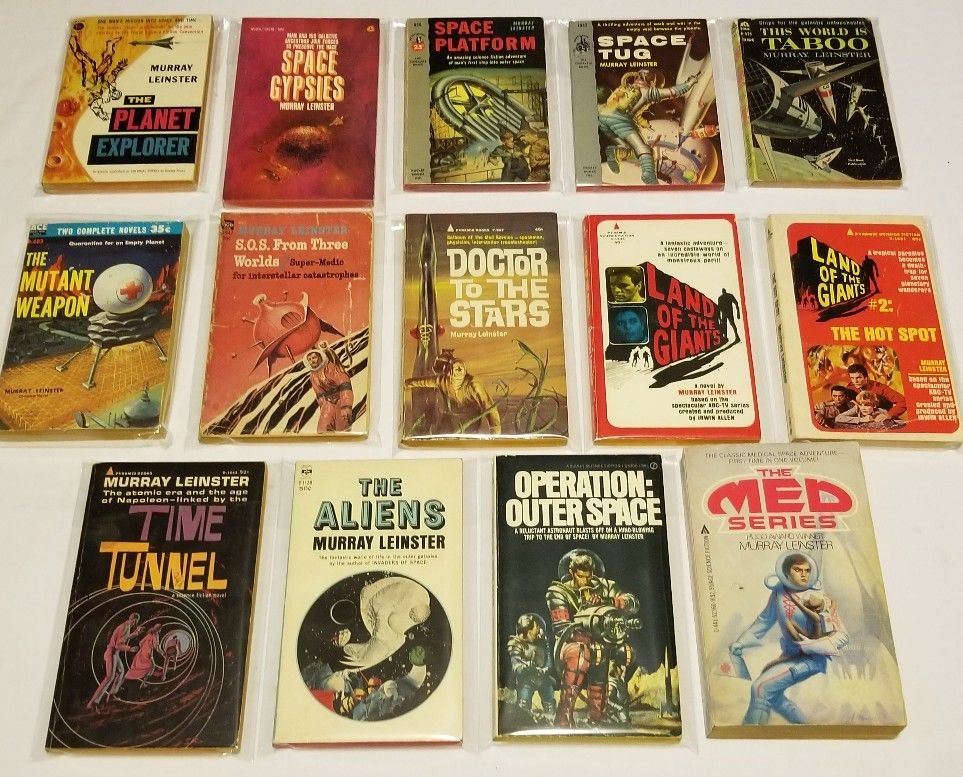

More vintage paperbacks by Leinster

Our previous articles on Leinster include:

Birthday Reviews: Murray Leinster’s “Pipeline to Pluto” by Steven H Silver

The Omnibus Volumes of Murray Leinster

Explore the Best of Early SF With Science Fiction From the Great Years

Vintage Treasures: The Brain-Stealers

Murray Leinster and the Moon by Tony Den

Vintage Treasures: The Best of Murray Leinster, edited by Brian Davis

Vintage Treasures: Gateway to Elsewhere

New Treasures: Planets of Adventure

Vintage Treasures: The Pirates of Zan

When Aliens are Delicious: Murray Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri” and the Creepy Side of Pulp SF

Vintage Treasures: The Best of Murray Leinster

Murray Leinster’s “Runaway Skyscraper” by Ryan Harvey

Fiction Excerpt: “The Fifth-Dimension Catapult”

And our previous coverage of the Classics of Science Fiction line includes (in order of publication):

Smugglers, Alien Vampires, and Dark Dimensions: The Best of C. L. Moore by James McGlothlin

Rich Playboys, Mad Scientists, and Venusian Monsters: The Best of Stanley Weinbaum by James McGlothlin

Vampires, Frozen Worlds, and Gambling With the Devil: The Best of Fritz Leiber by James McGlothlin

Space Colonies, Interstellar Fleets, and The Martian in the Attic: The Best of Frederik Pohl by James McGlothlin

A Neglected Master: The Best of Henry Kuttner by James McGlothlin

A Shaper of Myths: The Best of Cordwainer Smith by James McGlothlin

Wings, Wind, and World-Wreckers: The Best of Edmond Hamilton by Ryan Harvey

Shark Ships and Marching Morons: The Best of C. M. Kornbluth by James McGlothlin

Drawing Out What it Truly Means to be Human: The Best of Philip K. Dick by James McGlothlin

Wit and Play in Classic Science Fiction: The Best of Fredric Brown by James McGlothlin

Dead Cities, Space Outlaws, and Planet Gods: The Best of Leigh Brackett by Ryan Harvey

Gods, Robots, and Man: The Best of Lester del Rey by Jason McGregor

From the Pen of a Great Pulpster: The Best of Robert Bloch by James McGlothlin

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Good post! Leinster is underappreciated these days. One of the early SF greats.

Indeed. He gets my vote for next year’s Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award. Hard to believe he hasn’t won it already.

When I created a website in Leinster’s honor (back in the 90s), I was amazed to receive an e-mail from his daughter within 48 hours of the site going live.

Good post, James.

Leinster is a favorite that I need to revisit soon. I’m surprised, though, that you didn’t mention the Sidewise Award is named after “Sidewise in Time”.