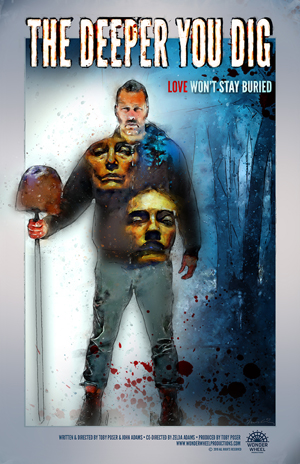

Fantasia 2019, Day 1-2, Part 1: The Deeper You Dig

Not long ago I acquired copies of two well-known anthologies: Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions.

Not long ago I acquired copies of two well-known anthologies: Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions.

(This post is not about the books. This post is the beginning of my coverage of the Fantasia International Film Festival, Montreal’s long-running three-week genre film festival, and is specifically about the first movie I saw there in 2019, an independent horror film called The Deeper You Dig. But it is useful to start with the anthologies, or the idea of the anthologies.)

I’ve yet to read deeply into the books. But I’d always wanted copies, because of the promise of the titles: the promise of art, of visions, that pose a danger to the audience. Stories that will do something to you if you read them. That will change you, in ways you might not understand, through a process you might beforehand perceive as a psychic danger. What I have come to realise is that the art that has meant the most to me has been the art that has changed me the most without my expecting it or being able to stop it. There’s a thrill in art that can rework you and refashion you into something else. It may be a danger, but without danger there is no real adventure.

It is perhaps accurate to say that one is changed by every kind of art, even by every experience one has. But it’s also true that there’s a specific kind of experience that art can give. The nature of this experience is difficult to articulate, but a change in the self that experiences the art is a part of it. In this way the influence of art is difficult to predict and difficult to trace in recorded history, yet is very real.

And this I think is why after several years, after learning much about film as artform and as industry, I’m still drawn to Fantasia. Not every film it shows is an aesthetic success. But many of them are. And many of them are the kind of works that can change you, in that most difficult to define fashion. You don’t know which ones until you watch them, mostly. But the act of finding out, of dedicating time to the perception and experience of art, is a reward in itself.

All of which is to say that on Friday, July 12, I set off to Concordia University’s downtown campus to see my first Fantasia movies of 2019. I’d start among the grey seats in the smaller 200-or-so-seat De Sève Cinema, to watch an independent horror movie that promised some intriguing imagery. And an interesting story behind the story. Apparently the old joke’s true: the family that slays together stays together.

All of which is to say that on Friday, July 12, I set off to Concordia University’s downtown campus to see my first Fantasia movies of 2019. I’d start among the grey seats in the smaller 200-or-so-seat De Sève Cinema, to watch an independent horror movie that promised some intriguing imagery. And an interesting story behind the story. Apparently the old joke’s true: the family that slays together stays together.

The Deeper You Dig is the product of a moviemaking family from the Catskill Mountains of New York State. John Adams, Toby Poser, and Zelda Adams collectively wrote, directed, shot, and starred in a film about a girl, Echo (Zelda), killed in a road accident by Kurt (John), a man fixing a house to flip. He decides to bury her, but doesn’t dig her grave deep enough to keep her spirit from haunting him. Meanwhile, Echo’s mother, Ivy (Zelda), a Tarot reader who’d been raising her daughter on her own, goes back to her old occult lore in a desperate attempt to find Echo.

It’s a solid horror story, but more than horrific, it’s suspenseful. It alternates between Ivy and Kurt’s point-of-view, setting up an inevitable confrontation — but not until after they meet and grow increasingly friendly, Kurt keeping his involvement in Echo’s death secret all the while. As you might guess from the title, bad decisions lead both protagonists further down dark paths. There’s genuine suspense as to whether one or both will be able to snap out of their downward spiral, not least because all three of the main characters are, if not sympathetic, at least relatable. Kurt’s clearly not a good man, but there’s enough recognisable in him that we willingly follow his story just as the dramatic structure of the movie insists. It’s not necessary to root for him to want to see what happens next to him, and what he does as a result.

It’s naturally easier to identify with Ivy, not least because of Toby Poser’s performance; Ivy’s increasing despair gives way to credible anguish at the death of her daughter. Her plot also hints at a larger mythic universe. This is a movie in which the supernatural’s clearly real, and the magic Ivy reluctantly takes up again to find Echo has a richness to its conception: there are books of magic, there are mysterious circles, there are strange images and visions that Ivy must negotiate to understand Echo’s fate. The magic here is intriguing enough that it feels almost bigger than the movie it’s embedded within; a larger story seen edge-on, a hint of a grander narrative, a glimpse of a huger world seen through brief surreal imagery and heard through evocative phrases and archetypal terms. In fact there’s probably just the right amount of magic, enough to whet the appetite and spark the imagination without mapping out every meaning.

Narratively, the weakest part of the film is the climax. It’s not actively bad; it’s logical, delivers on the promise of the rest of the movie, and in general the right things happen to the right people in the right order. But it feels rushed. It’s logical but abrupt. The Deeper You Dig is only 92 minutes long, but the denouement’s truncated, as though it would be a better fit for a short film. It is possible sometimes to be too economical.

Beyond that, the only aspect of the film that struck me as poorly-judged was the soundtrack. It’s an electronic, discordant score, which seemed to actively fight with the natural settings of the story — woods and hills, a stripped-down house filled with grey daylight, a snow-covered lake. The sounds of the score don’t seem to interact with the settings, and at times actively pulled me out of the film.

Beyond that, the only aspect of the film that struck me as poorly-judged was the soundtrack. It’s an electronic, discordant score, which seemed to actively fight with the natural settings of the story — woods and hills, a stripped-down house filled with grey daylight, a snow-covered lake. The sounds of the score don’t seem to interact with the settings, and at times actively pulled me out of the film.

Then again, that’s an issue partly because the settings are so well-shot. The majesty and threat of the frozen hills comes across, as does the sternness of late autumn and early winter. The geography of the house Kurt’s working on is unobtrusively but effectively established. Angles are imaginative, sometimes perhaps obviously so, but on the whole creatively-chosen. My understanding is that 15-year-old Zelda Adams was primarily responsible for the camera-work (as John Adams was for the directing and Toby Poser for the script) and she shows a real gift. The sequence after Echo’s death, a near-abstract play of headlights and thick night, is particularly strong. But the concreteness of the locations consistently comes across, as does the surrealism of Ivy’s more visionary experiences.

Crucially, the horror imagery is solid. A man coughs up blood and maggots. A hanged daughter looks down on her mother with a smile. Power tools, guns, a snow-covered countryside: a lot of things are established and shot as instruments of terror, and that comes across without being too obvious. If the final confrontation is not strong, the make-up effects are perfectly fine up to that point. Above all, Ivy’s visions succeed as visions, giving an impalpable sense of meaning: the nightmare sense of something you can’t touch, something you can’t point to, which is nevertheless intensely important.

Crucially, the horror imagery is solid. A man coughs up blood and maggots. A hanged daughter looks down on her mother with a smile. Power tools, guns, a snow-covered countryside: a lot of things are established and shot as instruments of terror, and that comes across without being too obvious. If the final confrontation is not strong, the make-up effects are perfectly fine up to that point. Above all, Ivy’s visions succeed as visions, giving an impalpable sense of meaning: the nightmare sense of something you can’t touch, something you can’t point to, which is nevertheless intensely important.

Ultimately, the characters and structure work. The drama’s always clear, and the contrapuntal plotting succeeds. The characters have clear desires and act logically on those desires, whether in mundane physical reality or the worlds of the spirit. Their decisions may not always be wise but are clearly motivated, creating a sense of tragic inevitability. The story keeps moving, and you sense impending doom all the while.

Which is about what you want out of a horror film. And this is a fine example of the genre. It’s not flawless, but it’s a film that works because of the solid build of the story structure. Also because of how effectively it establishes the supernatural, both as a casual reality and as a hint of something greater. Not too long ago I read an interview with a scholar who argued that horror, and especially horror film, was deeply marked by the imagery of World War I, which many great early horror directors saw firsthand; they developed an iconography of trauma still used in the genre. I like the argument a lot, but also believe there’s another tradition of an imaginative horror, whether gothic or cosmic, that acts differently. My point here is that I think The Deeper You Dig has elements of both strands. Murder and the death of a child; horror of trauma. Tarot readings and mystic texts; the gothic. Bringing these two things together, and incidentally tending to identify each kind of horror with each of the two leads, gives the film a richness that makes it intensely rewarding.

Which is about what you want out of a horror film. And this is a fine example of the genre. It’s not flawless, but it’s a film that works because of the solid build of the story structure. Also because of how effectively it establishes the supernatural, both as a casual reality and as a hint of something greater. Not too long ago I read an interview with a scholar who argued that horror, and especially horror film, was deeply marked by the imagery of World War I, which many great early horror directors saw firsthand; they developed an iconography of trauma still used in the genre. I like the argument a lot, but also believe there’s another tradition of an imaginative horror, whether gothic or cosmic, that acts differently. My point here is that I think The Deeper You Dig has elements of both strands. Murder and the death of a child; horror of trauma. Tarot readings and mystic texts; the gothic. Bringing these two things together, and incidentally tending to identify each kind of horror with each of the two leads, gives the film a richness that makes it intensely rewarding.

A question-and-answer period with the three filmmakers followed the film. As will generally be the case for live presentations and Q&A sessions, what follows comes from hastily handwritten notes. Asked how they got into film as a family, John Adams said that they’d started filming together 8 years ago in Los Angeles. They’d wanted to make films as a family, and ended up getting an RV, living on the road, and learning how to make films. It’s now five films later. Asked where The Deeper You Dig was filmed and how much it cost, Toby Poser said it was shot in the Catskills, where they now live, and cost $11,000.

Asked about the sound design, John said they’d wanted original sound, and so recorded noises made by a washing machine, a beat-up piano, a fan, and other implements in the house he was renovating — the same house the character of Kurt is fixing up in the film. They then took the sounds they’d gathered, and distorted them into something musical, so that the soundtrack of the movie comes from the house on screen. Zelda Adams recalled walking in the house, causing the floorboards to creak, and John saying the creak sounded amazing and to do it again.

Asked about the sound design, John said they’d wanted original sound, and so recorded noises made by a washing machine, a beat-up piano, a fan, and other implements in the house he was renovating — the same house the character of Kurt is fixing up in the film. They then took the sounds they’d gathered, and distorted them into something musical, so that the soundtrack of the movie comes from the house on screen. Zelda Adams recalled walking in the house, causing the floorboards to creak, and John saying the creak sounded amazing and to do it again.

To a question about the photography, John said it was mostly Zelda’s work. Zelda said that she’d gotten interested in the camera, and wanted to control its movement. They don’t have a steadicam, so the various camera glides in the film were produced in other ways. Toby Poser observed that nature gave the filmmakers much of what they needed, She recalled using a skateboard for a dolly, and for a climactic scene putting a camera on a bicycle and a frozen lake groaning under its weight.

Asked how the idea for the film came to them, John said “That is a great question that we should probably know the answer to.” Zelda observed that they’d created more realistic dramas before, and that Toby worked on the script as John shot an experimental horror short, which taught him lessons he was eager to explore in a feature. A discussion about the way the end of the climactic confrontation was shot followed, with John noting that they had a specific person advising them how to shoot an effect in a certain way, and expressing satisfaction that a laugh came at a certain point. In response to another question, he said that his test film worked out some cinematographic ideas, while Toby brought arcs and structure to the feature.

Asked if they had a unified taste in horror, Toby said they had three different lenses for creating, with some overlap between their visions. Asked if it was luxurious for them to be able to take a year to shoot a film and not have a deadline, Zelda said they were very lucky to be a family and be able to talk over ideas on the way to soccer practice. Living where they shot the film, they can see (for example) when snow falls, see where to shoot it, and get the shot right away. John said everything was there for them to shoot — they used their houses and their car, for example. So they can see what the weather looked like, and go shoot whatever location they needed. He’s not sure they’d actually go through a studio system, since he’s afraid they might be lost without that.

Asked if they had a unified taste in horror, Toby said they had three different lenses for creating, with some overlap between their visions. Asked if it was luxurious for them to be able to take a year to shoot a film and not have a deadline, Zelda said they were very lucky to be a family and be able to talk over ideas on the way to soccer practice. Living where they shot the film, they can see (for example) when snow falls, see where to shoot it, and get the shot right away. John said everything was there for them to shoot — they used their houses and their car, for example. So they can see what the weather looked like, and go shoot whatever location they needed. He’s not sure they’d actually go through a studio system, since he’s afraid they might be lost without that.

Asked about their other films, they said the movies are on Amazon Prime or their website, Wonder Wheel Productions. Asked about the image of a frightening clown in the film and its inspiration, Toby said John designed it, and that it was fun to do; Zelda used to be terrified of clowns. John said he experimented with the make-up effect in the short film he did, and still finds the image unbelievably sad.

That ended the Q&A, and my first screening at Fantasia 2019. I had a brief rest, and then two more films. I could only hope more dangers awaited.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.