Blogging Marvel’s Master of Kung Fu, Part Four

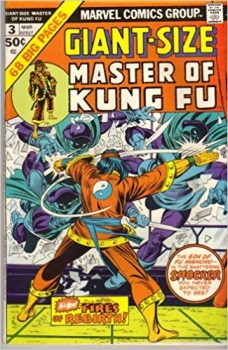

Giant-Size Master of Kung Fu #3 continues the run of excellent issues from writer Doug Moench and artist Paul Gulacy. While the early cycle of stories suffer from an over-reliance on Fu Manchu as the villain (to levels that rival Baron Mordo in the early Lee-Diko Dr. Strange stories), there was a method to their madness. The blowback from Sax Rohmer fans (which started in the pages of The Rohmer Review fanzine) was followed by the author’s widow filing a complaint with The Society of Authors over Marvel’s mismanagement of her husband’s property.

Giant-Size Master of Kung Fu #3 continues the run of excellent issues from writer Doug Moench and artist Paul Gulacy. While the early cycle of stories suffer from an over-reliance on Fu Manchu as the villain (to levels that rival Baron Mordo in the early Lee-Diko Dr. Strange stories), there was a method to their madness. The blowback from Sax Rohmer fans (which started in the pages of The Rohmer Review fanzine) was followed by the author’s widow filing a complaint with The Society of Authors over Marvel’s mismanagement of her husband’s property.

Steve Englehart and Jim Starlin had no way of knowing that killing off an old character in Shang-Chi’s debut would constitute not keeping to the tone and content of the originals. They were a writer and artist assigned to a property and were more interested in creating a Marvel variation on the successful Kung Fu television series than they were in reviving Fu Manchu. Moench and Gulacy were determined to avoid further legal hassles by showing something approaching fidelity to Rohmer while carefully positioning the storyline to more closely model Ian Fleming and Len Deighton spy thrillers than Rohmer.

That said, reader frustration with Fu Manchu turning up time and again in the monthly comic, the monthly companion magazine, and the Giant-Size quarterly was increasingly expressed in the letters pages of the three Shang-Chi titles. This penultimate issue of the Giant-Size quarterly is notable for the introduction of Clive Reston, a character who counts both Sherlock Holmes and James Bond in his immediate family in Doug Moench’s knowing wink to Philip Jose Farmer’s Wold Newton universe.

There are numerous strong action setpieces throughout, among them the introduction of the Si-Fan assassin Shadow-Stalker, but the issue’s high point is the climactic revelation that Fu Manchu has kept Dr. Petrie captive all these months and Shang-Chi did not actually kill him in his debut issue. This revelation not only clears Shang-Chi’s name, but more importantly, rights perceived wrongs on the part of vocal Rohmer fans and the Rohmer Estate’s legal representatives.

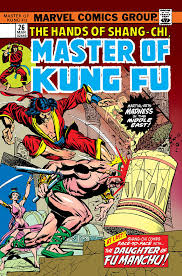

Of course, this issue was only the appetizer for what followed. Master of Kung Fu #26 saw the unexpected introduction of Fah lo Suee, the daughter of Fu Manchu direct from Rohmer’s novels. Egyptian locales from Cairo to the pyramids recall Rohmer. More importantly, Fah lo Suee’s seduction of archaelogist Robert Greville hearkened back to the books and incorporated a character intended to be the son of Rohmer’s Shan Greville and Rima Barton. The explanation that the Si-Fan has split into two factions, one loyal to Fu Manchu and the other to his daughter is also derived from Rohmer. However, the flashback to young Shang-Chi in a Chinese temple was borrowed directly from the Kung Fu television series. The only minor disappointment in this first chapter of this three-part storyline is that Keith Pollard was substituting for Paul Gulacy, though their styles mesh relatively well.

Of course, this issue was only the appetizer for what followed. Master of Kung Fu #26 saw the unexpected introduction of Fah lo Suee, the daughter of Fu Manchu direct from Rohmer’s novels. Egyptian locales from Cairo to the pyramids recall Rohmer. More importantly, Fah lo Suee’s seduction of archaelogist Robert Greville hearkened back to the books and incorporated a character intended to be the son of Rohmer’s Shan Greville and Rima Barton. The explanation that the Si-Fan has split into two factions, one loyal to Fu Manchu and the other to his daughter is also derived from Rohmer. However, the flashback to young Shang-Chi in a Chinese temple was borrowed directly from the Kung Fu television series. The only minor disappointment in this first chapter of this three-part storyline is that Keith Pollard was substituting for Paul Gulacy, though their styles mesh relatively well.

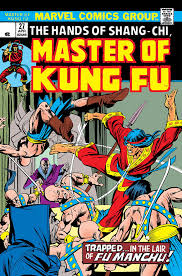

Issue #27 sees the setting shift to New York where the murder of a Hare Krishna follower leads Shang-Chi to infiltrate a meeting of the Council of Seven. He confronts his father directly for once and instead of the raving madman of past appearances, Fu Manchu is given a calm dignity and underlying menace as the two discuss not only their differing philosophies, but the familial conflict between father and son.

Issue #27 sees the setting shift to New York where the murder of a Hare Krishna follower leads Shang-Chi to infiltrate a meeting of the Council of Seven. He confronts his father directly for once and instead of the raving madman of past appearances, Fu Manchu is given a calm dignity and underlying menace as the two discuss not only their differing philosophies, but the familial conflict between father and son.

Shading Fu Manchu to be less of a villain and more an irreconcilable ideological opposite comes directly from Rohmer, but the added depth of family conflict is all Moench’s work. Their extended dialogue is excellent and easily the highlight of this middle piece of the three-part storyline. John Buscema’s artwork gives the issue more of a 1960s feel at times, which is certainly not a criticism. Unfortunately, Buscema tends to make Shang-Chi resemble a certain Cimmerian barbarian hero that was quite popular for Marvel then and now.

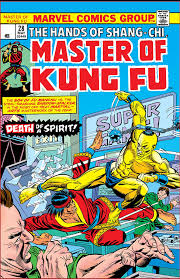

Issue #28’s conclusion is slightly disappointing after the strong build-up. Partially, this is due to Moench’s decision not to resolve the war within the Si-Fan so much as to set it up for a larger storyline later. The importance of the issue is now that the supporting characters are more recognizable as Sax Rohmer’s creations, they could be set aside while Moench worked at developing a new direction for the book. Ron Wilson’s artwork here is servicable as substitutes go. The return of Shadow-Stalker and a somewhat dissatisfying attempt to position Fah lo Suee as her father’s equal are the real meat here once the reader accepts that Moench is sowing seeds for a larger-scale conflict at a later date rather than advancing the plot.

Issue #28’s conclusion is slightly disappointing after the strong build-up. Partially, this is due to Moench’s decision not to resolve the war within the Si-Fan so much as to set it up for a larger storyline later. The importance of the issue is now that the supporting characters are more recognizable as Sax Rohmer’s creations, they could be set aside while Moench worked at developing a new direction for the book. Ron Wilson’s artwork here is servicable as substitutes go. The return of Shadow-Stalker and a somewhat dissatisfying attempt to position Fah lo Suee as her father’s equal are the real meat here once the reader accepts that Moench is sowing seeds for a larger-scale conflict at a later date rather than advancing the plot.

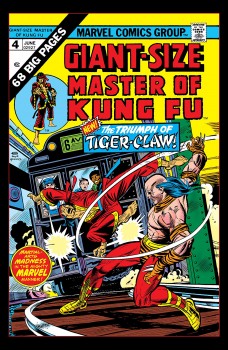

The fourth and final issue of the Giant-Size quarterly marked the return of Keith Pollard as a substitute for Paul Gulacy. It should be noted that Marvel’s  Giant-Size quarterlies all had a shelf-life of just over a year and then the promotion ended. Shang-Chi’s finale is centered around yet another Si-Fan assassin, Tiger Claw, but the issue belongs to wise guy cabbie, Rufus T. Hackstabber. The Marx Brothers were going through a revival during this period with yet another generation adopting their anarchic spirit and viewing their counter-culture humor as something other than an immigrant’s flagrant disregard for the conventional. The character of Hackstabber and much of his dialogue throughout are meant to recall Groucho Marx’s persona right down to the glasses, greasepaint moustache, and ever-present cigar.

Giant-Size quarterlies all had a shelf-life of just over a year and then the promotion ended. Shang-Chi’s finale is centered around yet another Si-Fan assassin, Tiger Claw, but the issue belongs to wise guy cabbie, Rufus T. Hackstabber. The Marx Brothers were going through a revival during this period with yet another generation adopting their anarchic spirit and viewing their counter-culture humor as something other than an immigrant’s flagrant disregard for the conventional. The character of Hackstabber and much of his dialogue throughout are meant to recall Groucho Marx’s persona right down to the glasses, greasepaint moustache, and ever-present cigar.

From the bank heist gone wrong opening, it is clear this is a decidedly offbeat issue. That said, the surfeit of humor does not prove to be the issue’s undoing. Fu Manchu and his mistress Ducharme (making a welcome return to the title) are handled deftly and kept largely in the background. Tiger Claw suffers from following too closely on the heels of the superior Shadow-Stalker. Perhaps for this reason, Moench opts to focus more of the story on two luckless bankrobbers working for the rogue Si-Fan assassin. Impatient readers would have to wait until the next issue of the monthly comic for the new direction for the series to take hold and to welcome the return of Paul Gulacy as artist.

William Patrick Maynard is a writer and film historian. His commentaries have appeared on releases from MGM, Shout Factory, and Kino-Lorber. He is the authorized continuation writer for the Sax Rohmer Literary Estate and is the author of new Fu Manchu thrillers for Black Coat Press.

“Moench and Gulacy were determined to avoid further legal hassles by showing something approaching fidelity to Rohmer while carefully positioning the storyline to more closely model Ian Fleming and Len Deighton spy thrillers than Rohmer.”

That, right there, was where the series went from kinda cool to great. Moench is one of the underrated legends of comics.