Arok the Robot

Arok the robot first hit the national news in June 1975 when it married Linda Hoffman, the president of the Allan Kemp Fan Club, at the annual convention of fan club presidents in Chicago.

I’ve long ago concluded that the modern world is one long real-time game of MadLibs. Even so, if that sentence doesn’t make you sit bolt upright in front of your screen then my whole career as a chronicler of robot history is a failure.

I had to look up Allan Kemp, a guitarist who was a founding member of Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band and a long time member of the New Riders of the Purple Sage. Linda Hoffman also swiftly falls out of this narrative. She’s important only because she shared the same sense of humor as her friend, the inventor of Arok, Ben Skora, a character too wacky for fiction.

The best introduction to Skora is fortunately preserved on video, from the time he was featured on George Schlatter’s Real People television show (clip below), one of dozens of tv appearances the canny showman made over the decades. Others included The Merv Griffin Show, The Phil Donahue Show, Ripley’s Believe It or Not, and Bozo’s Circus, believe it or not.

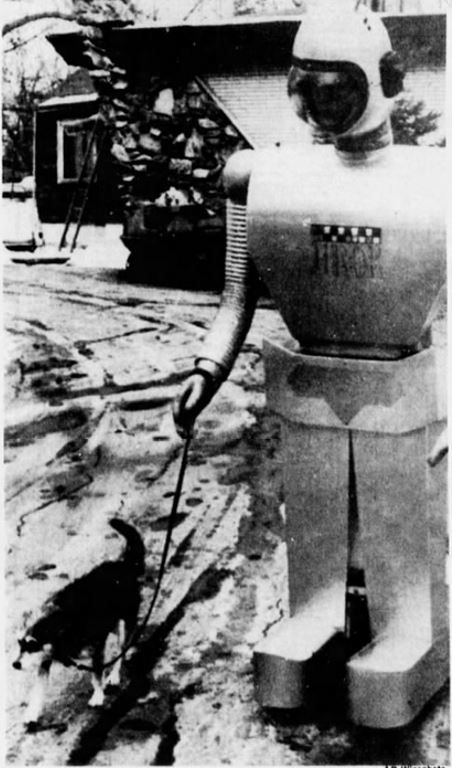

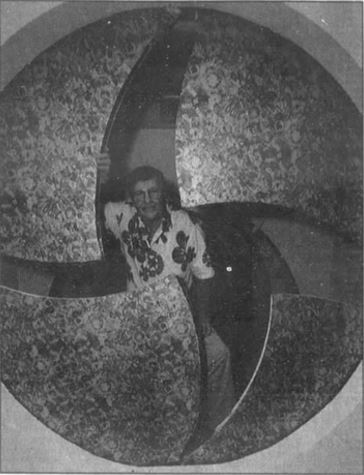

Skora, who was born in 1927 and lied about his age to enter the Army at 16, liked to brag that while he never even finished high school he was a born American tinkerer and trickster, who spent every hour he could spare in his day turning the world around him into a playground/toy box. His living room was built on a movable circular platform so that he could rotate the semi-circular sofa into the patio and bring the patio indoors. A touch tone phone controlled the drapes, opened drawers, and turned on the stereo and waterfall. His toilet was hidden beneath a giant potted plant that split into two at the touch of a button. A hidden portal was actually an elevator to his basement – the only entrance and exit, as his wife Sharon realized one day when the elevator broke while she was downstairs. (She acquiesced in this for 30 years but finally was driven out when, as she put it, the kitchen kept moving from side to side in the house.) Speaking of driving, Skora rigged his truck with a remote starter decades before it became standard. One day he turned it on outside a bar when his dog happened to be perched at the steering wheel. Another trucker came in wide-eyed at the dog’s ingenuity.

And then there was Arok.

|

|

|

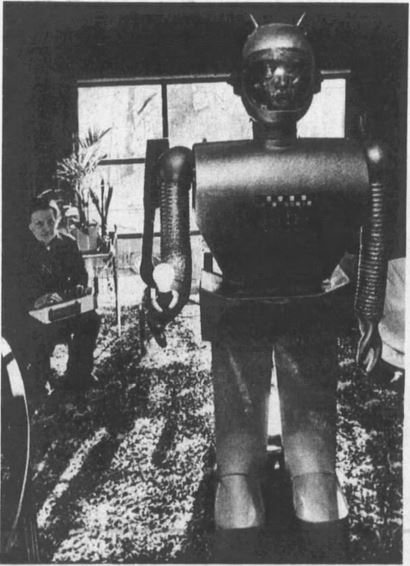

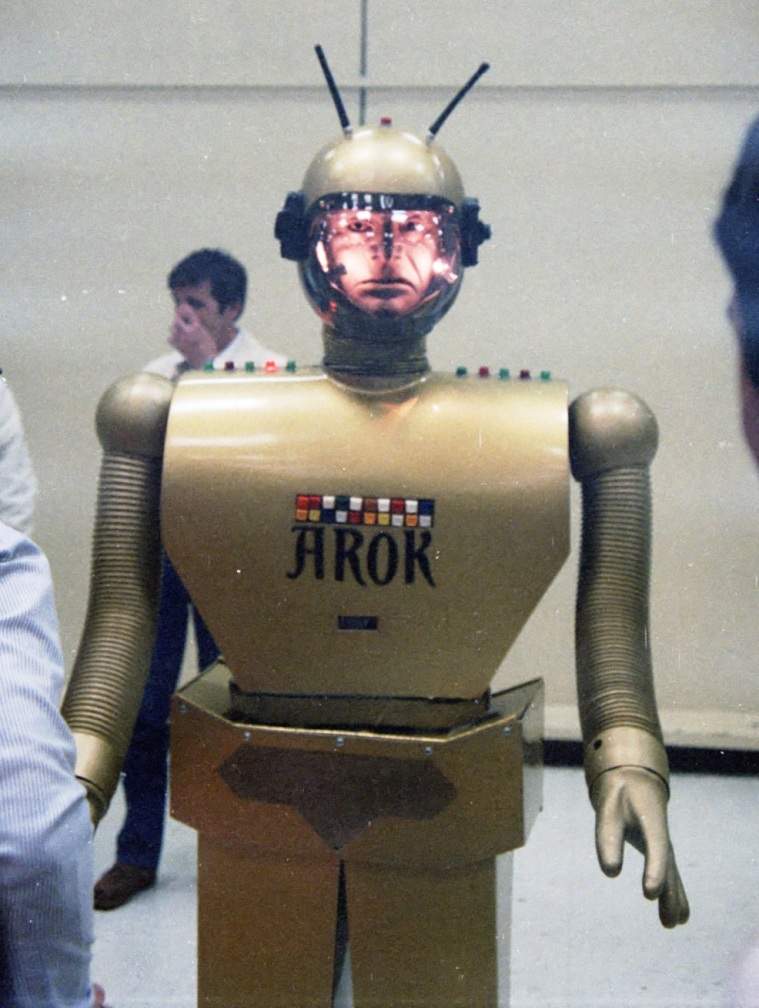

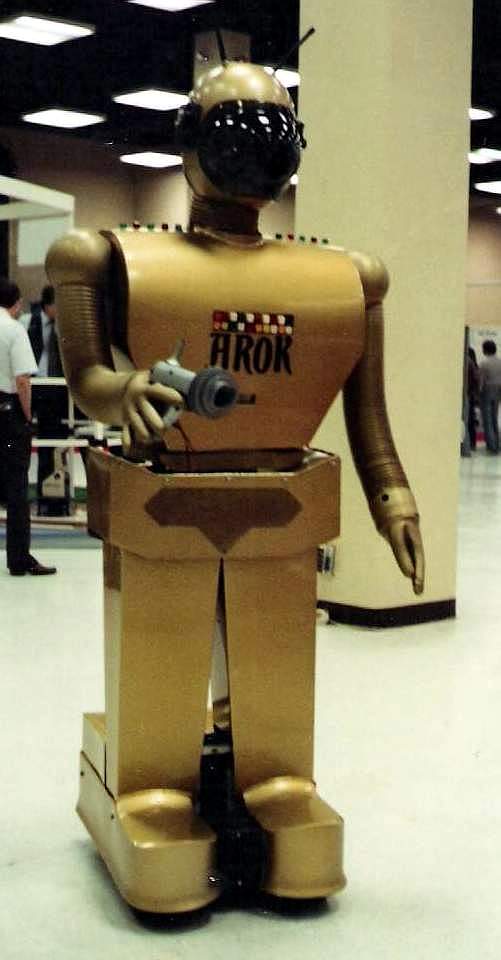

The only thing that a historian can safely say about Arok is that the name is Skora spelled backward without the “S”. Every other fact is mangled in ways that make one doubt about the entire journalistic profession. Arok was 6’4″ tall until it became 6’8″ tall except when it was 6’2″ tall. Its weight stayed steady at 275 lb., but its lifting strength was variously 125 or 150 lb., although one guy got confused and had it at 275 lb. It was insured for $1,000,000. (Really $75,000.) Or maybe that million was what Arok cost Skora in labor time, although that might have been $800,000 or $750,000. How did Skora come up with that figure? He multiplied a $20/hour rate. Never mind that implies a minimum of 37,500 hours of work, rather a lot for the three years it took him to build Arok. Or was it six years, or even eight?

That confusing welter of figures comes from the approximately one zillion articles that splashed Arok over the pages of newspapers and magazines when the world descended on Palos Hills, IL in 1977 and 1978. An article in Interface Age (and isn’t that name a relic of the era!) gave the best description of his construction.

FRAMEWORK

The frame at the base is made of heavy angle iron. The entire upper frame is aluminum. The batteries are placed on platforms in the feet and the drive mechanism in the base. This gives the unit a low center of gravity. enabling it to bend over and lift weights without tipping over. He can bend at the waist to a 45% angle and turn the upper torso to the right and left.

The integument of the body is aluminum sheeting, hand formed and welded.

The “skull” is molded from fibreglas [sic] and the face shield is from a motorcycle helmet. The face inside the helmet is a rubber mask which covers the actuating mechanism for the jaws. [The mask was of Frankenstein Monster’s!]

The flexible neck enables the head to move forward, backward, right and left. This movement greatly enhances the lifelike appearance, especially during conversation. The electromechanical jaw actuators contain attachments to the inside of the mask at the mouth. A microphone and a speaker are contained in the head. As the operator talks into the microphone in the control panel, the robot jaw mechanism responds to the voice causing the lips to move.

The arms are jointed at shoulder, elbow and wrist. The arms can raise from the shoulders, the elbows can bend.

The rubber-glove-clad hands are designed on bushings and screwjacks which allow for grasp, roll and rock motion creating an uncanny illusion of humanlike motion.

AMBULATION

AROK moves at a variable speed from two to three mph, forward and backward on wheels with a turning radius equivalent to his own length. The wheels are set into the bootshaped housing for the batteries. Control of ambulation is achieved by telemetry and built-in program.

TELEMETRY

Three antennae in the head receive and transmit signals from the control panel through F.M. wavelengths. The tones are generated by conventional telephone pads. The control panel has a bank of buttons, each representing a field of function and corresponding to a motion function on either side of the robot. To raise the right arm, Button #1 is depressed; to lower the right arm, #2 Button is actuated; Button #3 raises the elbow up and #4 lowers it. The control pannel [sic] supplies the robot with 36 functions at present and an additional 36 functions are planned to be added in the near future.

Signals transmitted to the robot are filtered through a set of active filters then to relays for two-speed modulation of the motors in the various areas of the body. There are a total of 15 motors, all of them redesigned automobile electric motors connected to approximately 35 relays and hundreds of solid-state ICs and transistors.

|

|

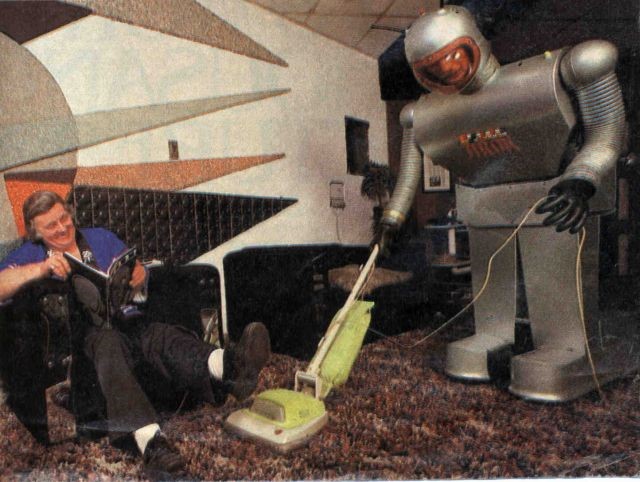

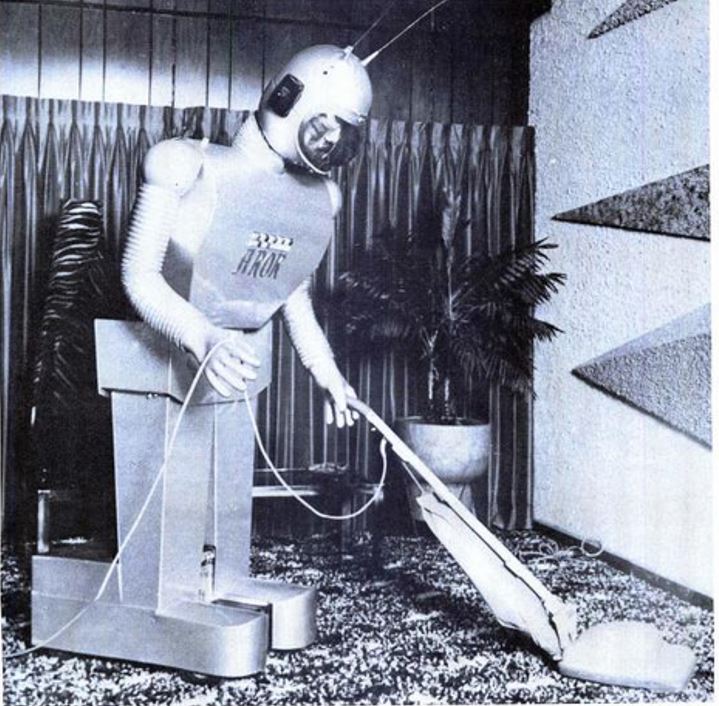

Arok was a throwback to the pre-World War II robots in many ways. That bronze-gold hue that it took on resembled Elektro, the Westinghouse robot at the 1939 World’s Fair. Also like Electro, it could not walk or speak or do anything on its own. Arok moved on rollers, spoke using words supplied by Skora over a microphone, and performed its chores, more accurately, tricks, by remote control. Also as was true of these oversized-for-awe early robots, though, it was an impressive figure, as an overwhelmed Time magazine reporter related in 1978.

When not engaged in light housework, Arok passes the day gazing sternly over the living room from his accustomed corner next to the TV set. He moves toward you quietly, with an air of intimidating strength. You know his limbs contain sensors that will short his circuits before he can crush your limbs, but you are reluctant to take his hand when he offers it. You know Arok’s master is putting words in his mouth from across the room through a microphone in an attache´ case-sized control panel, but you find yourself interviewing him with stiff formality. You know his name is Arok, but you want to call him sir. Your palms grow moist, and the room suddenly seems very small. When you point out with exaggerated amiability that his digital watch is an hour slow, he snaps, “That’s Mars time, dummy.” He does not suffer mortals gladly.

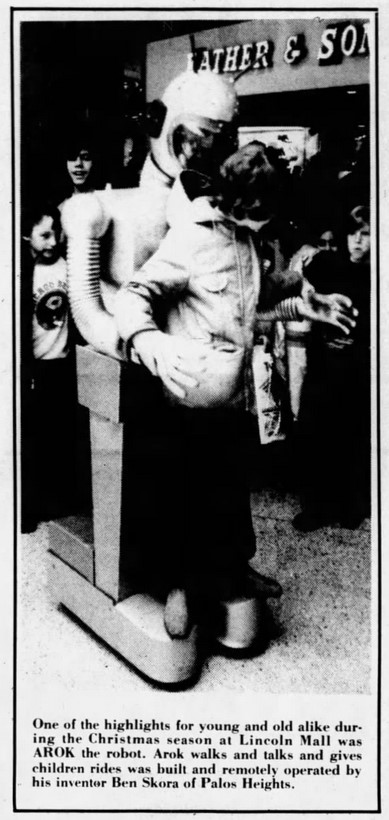

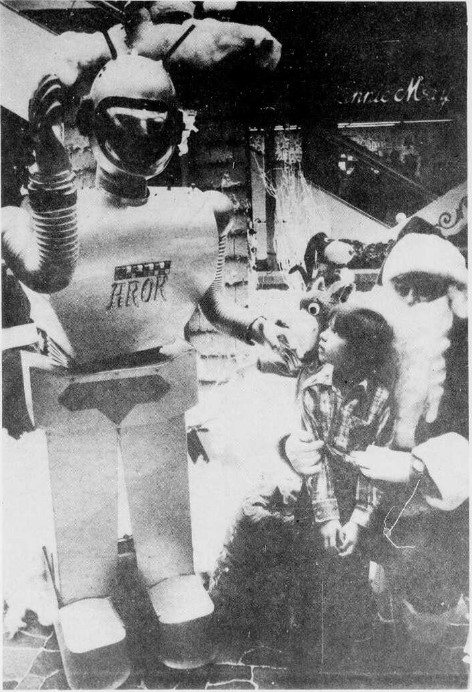

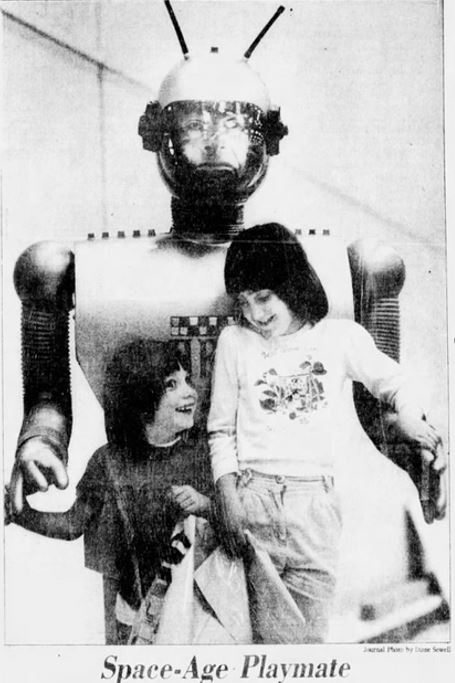

Skora made his costs back by renting Arok out for $450 a day and exhibiting it all over the Chicago area. I love the look on the little boy’s face as he sees something that, unimaginably, is more impressive than Santa Claus.

Time also noted that Skora made some attempts to exhibit Arok nationally, but these were fraught.

Still, Arok’s travels are not making his master rich. Liability insurance costs $150 a day. Skora has had to let his hypnotherapy practice dwindle to two or three patients a week. Lugging a 275 lb. tin man around the country is hard work; Arok must be carefully packed in his custom-built, veneered sarcophagus with the plywood bas-relief of him on the lid. And once on the job site, things go bump in the day. Like the time on a Chicago talk show when Arok impolitely dumped a glass of water into the laps of fellow Guests Bill Bixby, John Travolta and Barbara Eden. Or the time onstage in St. Louis when he was taking a little boy for a ride on the tops of his size 60 quadruple E tin shoes, got out of Skora’s FM range, demolished the scenery and broke himself in two. Asked the boy, who was unhurt: “Can you do that again?”

Robots were still part of the expected marvels of the future in the 1970s. Scores of articles referenced Arok as an example of the coming world. Headlines included “Robots: Waiting in the Future?,” “Elsie, the Mechanical Maid, Will Even Do Windows,” “Robots Aren’t Coming: They’re Already Here,” and my favorite, “First Law of Robotics: Have Fun with Inventions.”

Unlike most robots, which fade out of view when reporters’ eyes get captured by the next new thing, Arok kept up public appearances for decades. The Space Age Playmate picture is from 1984, when he was a hit at the first International Personal Robot Conference (the reporter shrinking it to a mere six feet). The Chicago Tribune did another feature on Skora’s house of whack in 1996, talking again about his round doors that dilated open like an old Heinlein story.

In 2001, Skora’s house became one of the odd dwellings featured in Chris Smith’s documentary, Home Movie.

Age comes onto to all of us, except for robots. Skora died in 2018, after several years of deep dementia in a nursing home. His fabulous home went to ruin and was eventually torn down. Amazingly, Arok was found, quite intact, in that protected basement. It now has a place of honor in the College for Technology building at the local Moraine Valley Community College. And still walks dogs.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was July 20, 2019 – As Seen from 1986 His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is finally available wherever books can be ordered over the internet. Visit his companion site RobotsinAmericanPopularCulture.com for much more on robots.

![1979-07-26 Morgan City [LA] Daily Review 4 Ben Skora Arok illus](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1979-07-26-Morgan-City-LA-Daily-Review-4-Ben-Skora-Arok-illus.jpg)

Thank you for your inventions Ben Skora. Ben was decades ahead of his time on future inventions.

Thank you for your inventions and service Ben Skora. Ben was decades ahead of his time on future inventions.

i love bens creations