The Golden Age of Science Fiction: Fantasia

The Balrog Award, often referred to as the coveted Balrog Award, was created by Jonathan Bacon and first conceived in issue 10/11 of his Fantasy Crossroads fanzine in 1977 and actually announced in the final issue, where he also proposed the Smitty Awards for fantasy poetry. The awards were presented for the first time at Fool-Con II at the Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas on April 1, 1979. The awards were never taken particularly seriously, even by those who won the award. The final awards were presented in 1985. The Film Hall of Fame Awards were not presented the first year the Balrogs were given out, being created in 1980.

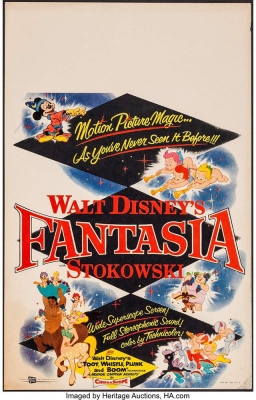

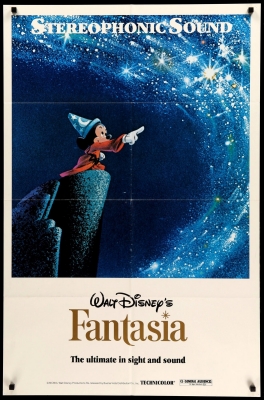

Released on November 13, 1940, Fantasia was the third feature length animated film made by Walt Disney, following on the heels of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio. The film built on the Silly Symphonies series of shorts Disney released between 1929 and 1939. While the Silly Symphonies married images to original music, Fantasia would take eight pieces of known classical music and use them to tell stories.

While Snow White and Pinocchio were aimed at a juvenile audience, Fantasia is very much a film for adults. The lack of dialogue, and what dialogue there is being expository, mean that, although certain sections of the film will appeal to children, most kids will be bored through much of the movie.

The first segment, Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” was given an abstract treatment by Cy Young, with some collaboration from Oskar Fischinger before he left the project. This is a rather strange choice to kick off Fantasia since rather than telling a story, as most cartoons tended to do, even the Silly Symphonies, the imagery for the Bach piece is entirely abstract, breaking with previous tradition rather than easing the audience into the new viewing experience.

Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker Suite” depicts the changing seasons and a variety of dances based on the types of dances from the namesake ballet. Paul Dukas’s “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” showing a mischievous Mickey Mouse trying to take a shortcut in cleaning up the wizard Yen Sid’s laboratory, is perhaps the most famous sequence. Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” is a look at the death of the dinosaurs.

Following an intermission, the orchestra is shown playing some jazz while a line denoting the soundtrack jumps around on the screen. Ludwig van Beethoven’s “The Pastoral Symphony” is used as the background music for a Greek mythological sequence. The piece shows a variety of mythological beings, ranging from fauns to centaurs to pegasi, enjoying the countryside until a storm comes up,. The Disney version of Zeus is shown to be something of a jerk as he targets Bacchus with the lightning bolts forged by Hephaestus before rolling over to get some more sleep.

Amilcare Poncielli’s “Dance of the Hours” provides a humorous take on ballet, showing ostriches, hippos, elephants, and alligators, among other creatures dancing. The final sequence begins with Modest Mussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain” as a night time of terror which gives way to a morning of hope with Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria.”

The introductions by Deems Taylor appear to be dry explanations of what is to follow, but they actually reveal Taylor’s wit if you listen closely. They are designed to replicate a musical appreciation concert in which the conductor would explain the piece about to be played so the audience would know what to listen for. The entire film is designed to give that feeling by showing the orchestra between pieces, complete with curtain opening and closing around the intermission and shots of the orchestra taking their seats and warming up.

One of the strange things about Fantasia is that even though Walt Disney released the film, when we watch it in 2019, we are not watching it in the manner Disney intended. It isn’t that we’re probably watching it at home, but rather that Disney meant for the film to be in a constant state of flux. He wanted the movie to be re-released to theatres each year with segments swapped out for new pieces of animation and new classical music. For a variety of financial reasons this never happened and the closest anything came was with the release of Fantasia 2000, which included almost entirely new materials, but included Fantasia’s iconic sequence for “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” The only other sequence from the original film to be re-used in the sequel was the introduction to the film by Deems Taylor.

For the first year of the Fantasy Film Hall of Fame Fantasia was selected over The Hobbit, King Kong, The Lord of the Rings, Nosferatu, Superman: The Movie, The Thief of Baghdad, Watership Down, and Wizards, only one of which, King Kong, would win the award in subsequent years.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I saw it in the movie theater a week after it was re-released in about 1956 or so and was amazed. I loved both the animation and the music. I don’t remember the voice over in that release, though. Though it’s not as popular, I like Fantasia 2000 as well.