What Skyrim Can Teach Us About World-Building

Good morning, Readers!

No one who knows me is surprised when I say I love video games. I’ve written about them previously for this very site. I think it’s hard to overstate just how much I adore video games (specifically narrative-focused games). The one game that got me to buy my first console and actually dive head-first into gaming was Bethesda Studio’s epic addition to their Elder Scrolls series, Skyrim.

This open world game lets you go anywhere, and do pretty much anything. Best of all, it has dragons (which you can kill and steal their souls to fortify your own powers [insert evil laugh]). Loving video games, but without a PC (my home computer is a Mac) or a console, I resorted to watching other folks have fun with them on YouTube. I stumbled across a Let’s Play of Skyrim, and after three episodes, I knew I had to play it for myself. I saved like a madwoman, bought myself a console, and Skyrim.

And I was never heard from again (not really. I did not ignore my responsibilities… but it was close!).

Skyrim proved to be everything I had been promised. It was epic in scope, the combat was fun, the dragons were amazing, and it let you play however you would like.

For the record, I always play in first person, and my build is always a bosmer (wood elf), whose strengths lie in archery and sneaking. There’s something ridiculously satisfying about sniping fools from the shadows with a good bow.

A Bosmer, with what looks to be the Nightingale Bow. My girl is paler, on account of it being a proxy of my own, ghostly self.

Not so recently, after many years away from the game, I once again loaded it up, and began to play. I felt immediately at home in the province of Skyrim. It’s the same sensation as cracking open a much-loved book. Since this is my… oh… fourth? Fifth? Something around there… time playing, I am able to detach a little from the wonder and the plummeting absorption of the game to marvel at its design, and the work that has been put into it; specifically, into the world-building.

(This isn’t to say that the game is without its issues, but this isn’t an article specifically about the game and game play, so I’ll spare you the hilarious, and sometimes frustrating bugs that can be found in the game… or my ire that is it the last of the Elder Scrolls games that can be played home alone without an internet connection. I don’t care for Elder Scrolls Online, Bethesda. I don’t want to play with other people. Give me my stand-alones, damn it! Ahem… where was I?)

In the game, Skyrim is the northern-most province of Tamriel, the continent in which all the Elder Scrolls games take place. It is the homeland of the Nords, a people styled after the medieval Scandinavians (known by most as Vikings) of real-life Europe. You, the player, are plunged into the world of which you know nothing about, seated on the back of a wagon with, as it turns out, the leader of the Stormcloaks — freedom fighters trying to with the province’s independence from the empire (which appears to be a proxy of ancient Rome) — on the way to an execution. Great.

It is at the execution site, a township called Helgen, that you get to select your race, gender and design your character’s appearance. I usually take forever here.

Heh heh heh.

Moments before your execution, for the crime of… nothing, it seems, a dragon attacks, and the game proper begins.

As I said before, the game play is fun, the story is great, but what really impressed me was the world-building. Skyrim feels lived-in. It feels weighty and old, like it is a real place with real history. How the game developers managed this is worth exploring. It’s something fiction could benefit from, I feel, with a caveat; not all fiction needs to have worlds that feel weighty and old and lived-in, but many could use it.

A video game like Skyrim has a visual advantage that novels do not get. In game, you are greeted with the ruins of all kinds of buildings. Collapsed and collapsing towers, presumably once built and maintained by the empire, but now lie empty or house bandits, dot the landscape. The smoldering remains of the Hall of Vigilants, which comes to play as part of the story, can be happened upon in one’s travels throughout the province at any time. There are deserted shacks, or the remains of them. My favorite was nothing more than a free-standing door frame by the side of a road.

You get to explore the ruins left behind by the Dwemer, who just mysteriously vanished without a trace (but whose steam-punk style machines still function), or barrows and temples that are thousands of years old and no longer in use.

My favorite visual clue of the antiquity of the world is in the very frozen north. If you explore a little, you can come across a mammoth frozen in the ice. The best part is, all manner of weapons are frozen with it, indicating that this mammoth was killed, only to be covered in ice moments later. It was a brilliant visual that lent itself well to the feeling of history held by the world.

I thought the frozen mammoth was so cool, I took a screenshot of it.

Writers do not really have the luxury of throwing up a few pictures and landscapes in the book with these visual clues. For that reason, I think, they’re often neglected. I’m here to beg you not to neglect them. A writer needn’t spend a great deal of time on these details to make them effective. A lengthy Tolkien-esque description of a ruin, along with its entire history before ruination, the hero passes is not required. However, a few words spared, or a sentence here or there, would not go amiss.

Steven Erikson, of whom I am a huge fan, manages this brilliantly in his Malazan Book of the Fallen series. I still to this day, though it has been years since I read the book, can recall the scene where three unlikely travelers are crossing a desert. For a brief moment, Erikson takes the action away from the group to describe how the wind uncovers a few shards of archaic pottery, evidence of a long-forgotten civilization, only to cover it over again with blowing sand. That one small description, unnecessary to the action at hand (crossing the desert), added such depth and weight to the world and was, in fact, one of the things that stuck most with me. I have in my mind now a painting of that exact moment, forever branded.

There are other things that Skyrim does that writers could take a cue from. The characters of the game are thoroughly embedded in the events, and it’s history, both ancient and recent. The fallout of things that happened before you arrive there play out before your eyes. Things happen in the periphery, and as part of your journey. Mysteries exist in the world that the hero won’t solve (what the hell happened to the Dwemer?), and remnants of a glorious past are met (fare thee well, Knight-Paladin Gelebor. I pray you are not truly the last of the snow elves), but don’t really have an effect on the main story at hand. The whole province is reeling from the White Gold Concordant, and the Thalmor crack-down on Talos worship. This just exists. It’s a part of the world. It started before you even arrive, and it is something that the hero — you — don’t solve.

Having things like this in one’s book helps flesh out the world, makes it feel like a real place. This doesn’t mean that someone need dedicate a thousand pages to the history of the world, or the political climate. It is, however, something to keep in mind as you have your hero move through the world. There is a history there; old enmities, ancient battles, recent joys, legends and lore. Making mention of them, in some form or another, will help build a world a reader can fall into and explore.

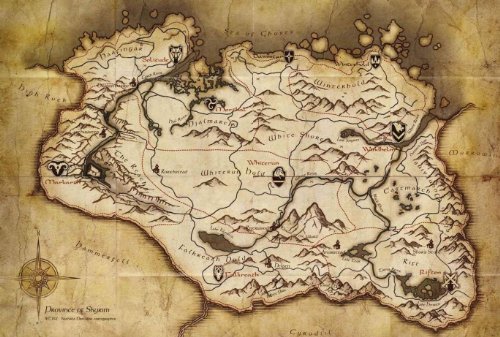

Fancy maps don’t build a world. I mean, they don’t hurt, either. I want this one on my wall.

As a reader, I long to fall down the rabbit hole and into a world that is not my own. It’s one of the great pleasures of reading. Creating a world with a real history that the characters relate to, and is the lens through which current events are happening is a huge part of what enables me to fall so helplessly into a narrative. Not all stories require this kind of depth, but many would be improved by it.

Perhaps this is just the longing of someone who is not intimidated by massive tomes (rather, I’m enticed by them, because they promise a world that feels real), and few readers may share this desire. However, one of the joys of Skyrim, the thing that keeps me returning time and again, is the world, and how full, deep, and real the developers have made it feel.

Just something to keep in mind when writing your next opus.

When S.M. Carrière isn’t brutally killing your favorite characters, she spends her time teaching martial arts, live streaming video games, and cuddling her cats. In other words, she spends her time teaching others to kill, streaming her digital kills, and cuddling furry murderers. Her most recent titles include ‘Daughters of Britain’ and ‘Skylark.’ www.smcarriere.com

As the former Loremaster of The Elder Scrolls Online, let me just point out one of several methods Elder Scrolls designers use to make the world feel lived-in: all history, lore, and culture is conveyed from the viewpoints of characters who live in the world, and everyone has their own agenda. There’s no single source of truth, no Silmarillion, no Dungeon Master’s Guide, just people and what they tell you or what they write in books or journals. The “unreliable narrator” effect rules every interaction. That one guiding rule makes the world of the Elder Scrolls rich, various, and strange.

Yes! Thank you. Good point. This would also work in fiction, and is sometimes quite lacking.

I refer to all those wonderful found tidbits as snippets of story. I also replayed the game after years away (ignoring the main story line and just exploring), and that’s when I found my favorite snippet. In a barren spot, in a gap between two rocks, was a dead sabre cat full of arrows. The skeleton of an archer was nearby. A leftover fragment of high drama that will forever remain anonymous and had no bearing on a story line.

I put about 400 hours into Skyrim on my first install, yet didn’t find the remnants of that anonymous battle. What else did I miss?

I put quite a bit of time into the most recent Witcher title but eventual quit because the world was shallow. Almost no story snippets. The one standout I found (and for all I know, it could have been part of a quest) was on the backside of an outlying island where I found wolfsbane growing, along with a dead werewolf and a few dead men. At that moment I experience wonder like no other time in that game. Were they hunting the werewolf? Was the werewolf their friend who turned moments before getting a cure? Delicious possibilities.

And now for something completely different, I’ll never play an Elder Scrolls MMO (or any other MMO, for that matter), but my and my wife’s biggest lament over Skyrim is that we can’t play it cooperatively. That would have almost made it our perfect game. (As I understand it, there are some mods that are getting pretty close.)

I… I have not come across that in any of my play throughs! I must find it now! And yes, I think a co-op would have been great (imagine having a companion that didn’t run in front of you just as you loosed your arrow, getting themselves one-shotted)! I played The Witcher 3, but didn’t stay in the world past completion of the main story for the exact reason you stated. The world was shallow and, while pretty, largely uninteresting.

But story snippets aside, I must admit my favorite thing to do in the game is to drop down on a bandit-held fortress from above; stealth through it; slitting all the throats; and walk out the front door without having triggered a reaction.

Imagine some future hero finding _that_ story snippet! 😉

Stealth really is the way to go, though my preferred weapon is the bow. And now my brain is using your slaughter as a story prompt. So… Thanks!

lol. You’re quite welcome.

Interesting item of small note: The Hall of Vigilants is not smoldering if you get there early enough in the game. I went there hoping to be a druid and the possibility of different quest lines.

Wait… really? I’ve been fairly early in the game, and always found it in ruins. Huh. I’ll have to load it up again when I’m done this play through and check it out.

TES lore has several flaws. It feels like, at least in the more modern games, BGS has partially abandoned internal realism for cool ideas, or for seemingly no reason at all. What is even the point of taking my weapons away in jail if you don’t also take away my magic (something that morrowind did), which allows me to just unlock every door, summon an arsenal of weapons, create an army and blast my way out of there. Why do the people at the entrance of Windhelm go from accusing all dark elves of being Thalmer spies, then turn 90 degrees and explain to an elven player character exactly why they hate dark elves? Skyrim’s lore is wide as an ocean, but deep as a puddle. Compare this to something like Death Stranding’s lore, where the rain causes things to age. As a result of this, the only things alive are a few trees, grass and moss, because all other things either die to quickly or don’t reproduce fast enough. People will use anything they can to their advantage. In Skyrim, there is a spell that transmutes iron ore into gold. In a gold based economy… Germany after WWI dealt with less hyperinflation than would come from this. Contrast this once again with Death Stranding, where the timefall is being used to age beer because humans are going to human.