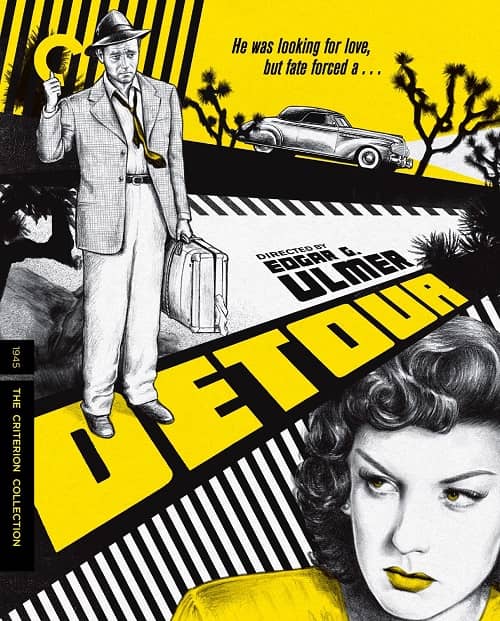

A One-Way Trip on the Road to Hell: Detour Gets the Criterion Treatment

I love extra features on Blu-rays and DVDs. I don’t just listen to commentaries, I listen to dull commentaries. I watch restoration comparisons and making-of documentaries. I listen to audio-only interviews with scriptwriters, production designers, and character actors. I ponder the effects of deleted scenes and alternate endings. I scrutinize stills galleries. I watch compilations of grainy on-location footage shot by local news stations. I read inserts and booklets, alternately nodding sagely and muttering sharp disagreements under my breath.

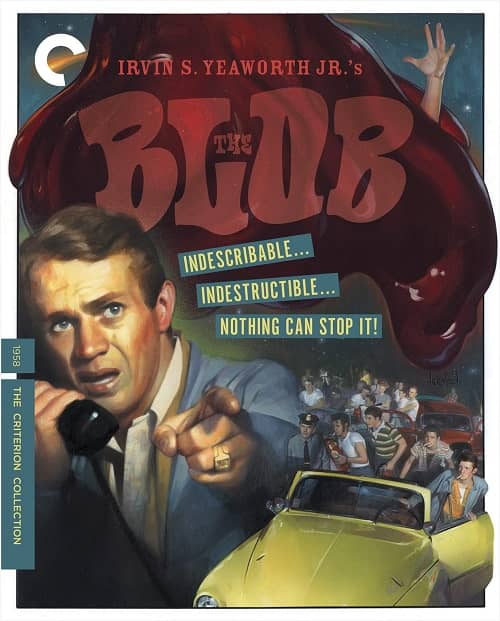

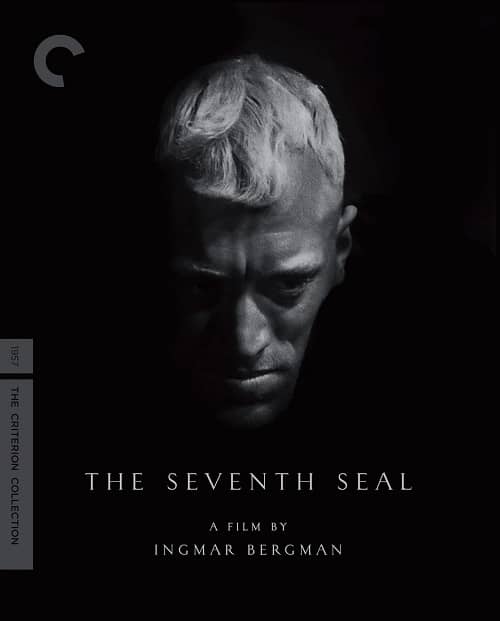

In short, I’m a Criterion junkie. For those throwbacks who still buy physical copies of movies, Criterions are the gold standard, both for image quality and extras, to say nothing of the wide range of films in the collection, which includes movies as radically different as The Blob and The Seventh Seal. The company itself boasts that it is “dedicated to gathering the greatest films from around the world and publishing them in editions of the highest technical quality, with supplemental features that enhance the appreciation of the art of film.” You’ll get no argument from me.

Every month I get an email from Criterion (they know when they have a fish well hooked) announcing six films that will be coming out in three month’s time. I always know that out of the eclectic mix of foreign films, American studio classics, indie sleepers, cult movies, and offbeat oddities, there will be one or two… or three… or four that I must have. (Just try finding Island of Lost Souls or Repo Man or City Lights on Netflix. Go ahead and try.)

|

|

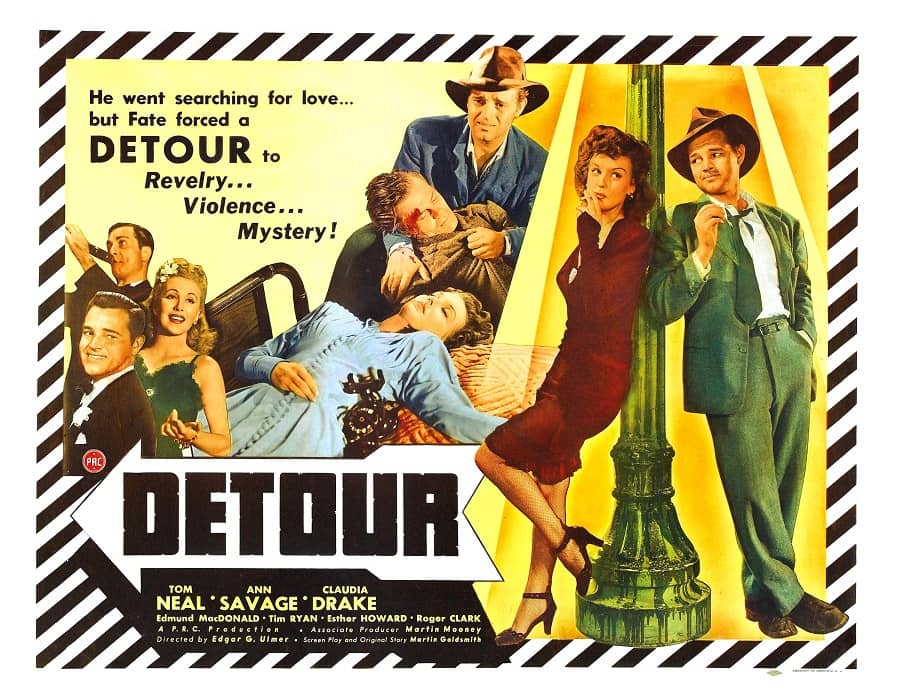

Every now and then, one of those emails literally makes me holler out loud. That was the case last December, when I saw that the 1945 noir masterpiece Detour would be coming out in March. I was more than normally excited because this Criterion edition is the first decent video release that this great film has ever had. Criterion numbers their releases; Detour is 966. My only complaint is that the number should have somewhere in the teens or twenties, but better late than never.

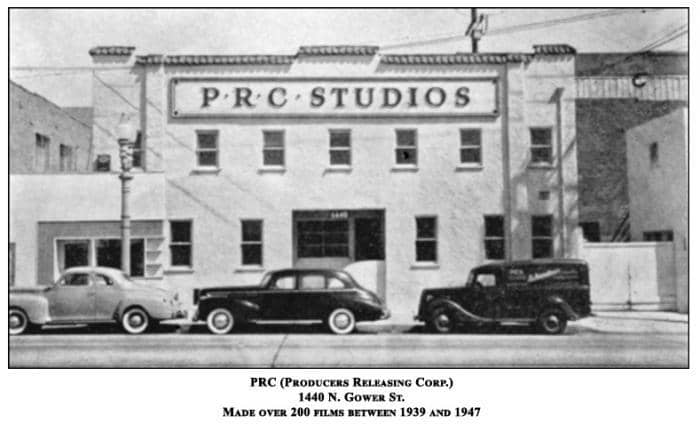

Why did it take so long? Perhaps because of the film’s “low” parentage. Detour isn’t a lavish, big-budget Hollywood production or a prestigious European art film; it’s a B Movie. In fact, it’s actually a B minus, in that it didn’t come out of the B units of a major studio like Warner Brothers or Universal or Fox. Those B Movies, cheap as they were, at least sometimes had significant resources behind them. Detour, on the other hand, came from Poverty Row, the bottom-of-the-barrel producers of nothing but ultra-cheap fodder for the low end of the bill.

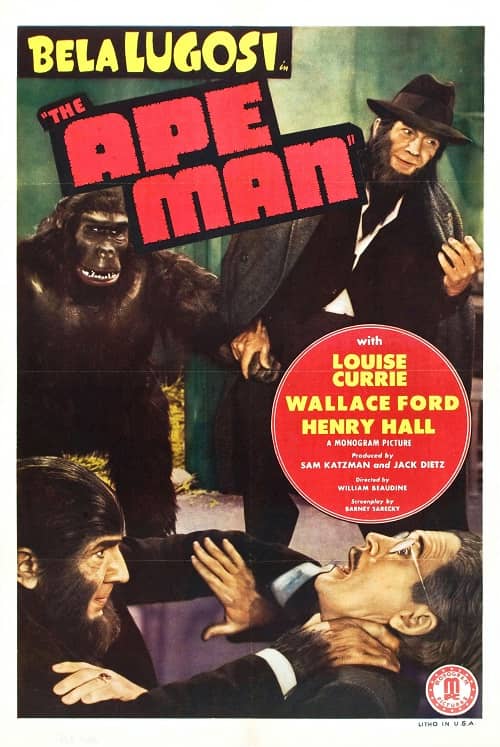

Poor Bela

Studios like Republic, Monogram, and Detour’s studio of origin, Producer’s Releasing Corporation (or PRC) made up a one-take purgatory of six day shooting schedules, fog machines (to mask the inadequacies of sets and costumes that would have barely made the grade at a high school drama department), slapdash scripts, stock footage, public domain music, and actors you never heard of (except for poor Bela Lugosi). No A pictures emerged from this wasteland; the whole region (largely centered around Gower Street in Los Angeles) was known colloquially as “the B-Hive.”

The tossed-off westerns, mysteries, and horror pictures that came out of this sausage processor were — understandably — almost all just terrible. Even when they were better than that they were merely forgettable, and they have been forgotten — with a few exceptions. Detour is one of the rare Poverty Row films to establish a good critical reputation, a reputation that has grown stronger with the passing years until now this throwaway, hardboiled noir nightmare is universally acknowledged as a bona-fide classic, a pauper’s masterpiece.

Detour is a quintessential noir. The plot is a poisonous distillation of the genre’s essential elements: a hard luck chump meets an implacable femme fatale, and their increasingly antagonistic relationship is brought to a deadly consummation by the hand of fate itself.

The action begins when nightclub pianist Al Roberts (Tom Neal) decides to hitchhike from New York to Los Angeles, where his fiancée Sue has gone to try to break into the movies. Somewhere in Arizona, he’s picked up by a driver who turns out to be a flamboyant gambler named Charles Haskell Jr, the estranged son of a very rich man. Not far down the road, Haskell lets Al take over the driving while he gets some sleep. After a while it starts to rain, and Al pulls over to put up the convertible top. He tries to wake Haskell to get some help but is unable to rouse him, and when he goes around to the passenger side to open the door, Haskell falls out of the car and hits his head on a rock. Al then realizes that Haskell has died sometime during the night.

Al concludes that the police would never believe that he didn’t kill Haskell, and so he decides to hide the body in the desert and appropriate the dead man’s identity long enough to get into Los Angeles. Once there, he plans to ditch the car, find Sue, and resume his life. Before that can happen, though, he makes the fatal mistake of picking up a hitchhiker of his own, a brittle young woman named Vera (Ann Savage), who quickly ascertains that Al is lying about being Charles Haskell. She is able to see through his imposture because she actually knew Haskell!

Al realizes his mistake

Armed with this information, Vera puts the squeeze on Al, virtually holding him hostage until they get to L.A. where she intends to take all the money that they can get from selling Haskell’s car. Before that can happen, Vera finds out that the senior Haskell has just died, and she tries to bulldoze Al into presenting himself to the bereaved family (none of whom have seen the heir for a very long time) as Charles Jr. Once he’s inherited the Haskell millions, they can split the money and go their separate ways.

Al naturally thinks this scheme is crazy, and while the pair are holed up in the motel that Vera is keeping them imprisoned in, their arguments become increasingly heated until Vera threatens to call the police and tell them the real story of how Al wound up with Haskell’s wallet and clothes and car. Al tells her to go ahead, but as soon as Vera grabs the phone and locks herself in the next room to make the call, Al’s resolve fails, and he grabs the phone cord to try and pull it out of the wall… and instead unwittingly strangles Vera — the cord had gotten itself wound around her neck.

When Al sees what he has done, he flees the motel and hits the road again, convinced that there’s no escaping the malignant fate that has singled him out for destruction. The film ends with a despondent Al sitting in a roadside diner, imagining the inescapable moment when the police will come to pick him up. As he pictures himself riding away in the back of a patrol car to whatever dark end awaits him, Al tells us, “Fate or some mysterious force can put the finger on you or me for no good reason at all.”

Al’s dead end

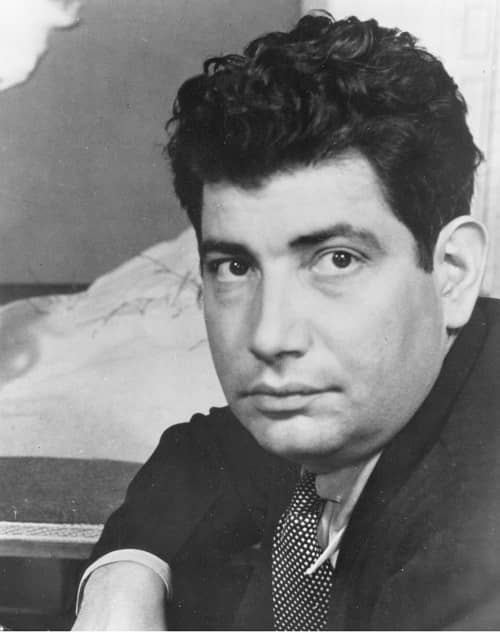

In a summary like this, Detour can sound like an absurd farrago, nothing but a grubby mishmash of clichés and improbable plot twists, but it has virtues enough to more than overcome the inherent defects of the wild story. At just sixty nine minutes the film never stops moving, especially once Al leaves New York; the director, Czech expatriate Edgar Ulmer, keeps the string of the plot pulled so tight that you never have a moment to reflect on how ridiculous the whole thing is. Instead of incredulity or skepticism, the only things you feel are Al’s mounting panic (because you’re trapped with Vera as much as he is) and the constantly increasing closeness of the unavoidable doom that is hurtling down on him.

In terms of production values, the movie is certainly cheap, but that very cheapness works in its favor. Much of the film was shot outdoors, on the road and in the desert, and this gives those sections a natural verisimilitude, while the bare, tacky indoor sets make the film’s low-rent atmosphere and sleazy events all the more believable. And what’s true of Detour’s physical elements is even truer of its players. In more respectable noirs, you never completely forget that that’s Robert Mitchum or Barbara Stanwyk or Humphrey Bogart that you’re watching. As brilliant and committed as those actors are, down deep you always know that they’re really movie stars.

Tom Neal and Ann Savage, though, are the kind of players that you can readily accept as actual people inhabiting a tawdry story like this. (No major studio noir protagonist would ever have been permitted to be as sweaty and grimy as Neal is in Detour.) They weren’t quite talented or lucky or glamorous enough to ever become familiar faces and so were almost completely unknown to the audiences of 1945 and are even more so now, unless you’re the kind of pathetic degenerate who DVR’s George Zucco movies (guilty, your honor).

Ann Savage and Tom Neal

Which is not to say that Neal and Savage aren’t excellent in Detour — they are. Their very anonymity makes them perfect, in fact. Neal is very fine as Al Roberts, a not-too-bright, self pitying schlub who can’t see that while there might indeed be such a thing in this world as an evil destiny, all along the way he’s given it a hell of a hand up with his boneheaded decisions. Neal’s somewhat blurry personality is just right for Al, who can never quite focus enough to understand his own complicity in his ruin. (Neal’s performance is even more disturbing in retrospect — twenty years after Detour, he served six years in prison for killing his wife.)

And as Vera, Ann Savage is truly extraordinary. Soft and gentle as a broken bottle shoved in your face, heartless, vicious, remorseless, Vera uses words the way Jack the Ripper used a knife. For her, each sentence is a weapon meant to slash through Al’s guard, to cut him, gouge him, destroy him. The scalding hatred and loathing that gush from her can’t just be about Al or the money; their only fit targets are the entire world and life itself. It’s a performance so bitterly strong it shatters the frame of the seedy little crime story that contains it, and once you see it you’ll never forget it.

With its portentous pronouncements about life and fate and its clankingly mechanistic plot, Detour ought to be laughable… but it isn’t. It was made with such drive and played with such force and conviction that its grim view of life as a senseless and inescapable trap seem perfectly apt and true, at least for the space of the movie’s running time. (You have to wonder how many people stumbled from the darkened theater in 1945 and went home to hang themselves.) It’s a little gem with edges so jagged they can still cut you to ribbons, a truly powerful and unforgettable movie that’s sharp with all the desperation appropriate to a film shot by hungry, disrespected people in just six days. It’s no surprise that it has survived its own destined oblivion when virtually all of its B-Hive brethren have vanished forever.

The Criterion edition does justice at last to this hellish story, most of all in the excellent print of the film, the best that anyone has seen since its original release almost seventy five years ago. One of the extra features is a documentary about the restoration process, and it’s a real detective story about a ten year long search for usable elements that concludes with a pristine print of the movie finally being discovered in an archive in Brussels, of all places. In addition to the usual booklet-with-essay (this time by the estimable Robert Polito, who focuses on the transition from Martin Goldsmith’s source novel to the finished film script), there are two extras about Detour’s amazing director, Edgar Ulmer. One is an interview with Ulmer’s biographer, Noah Isenberg, and the other is a seventy five minute documentary about Ulmer’s life and career, Edgar G. Ulmer: The Man Off-Screen.

Edgar Ulmer

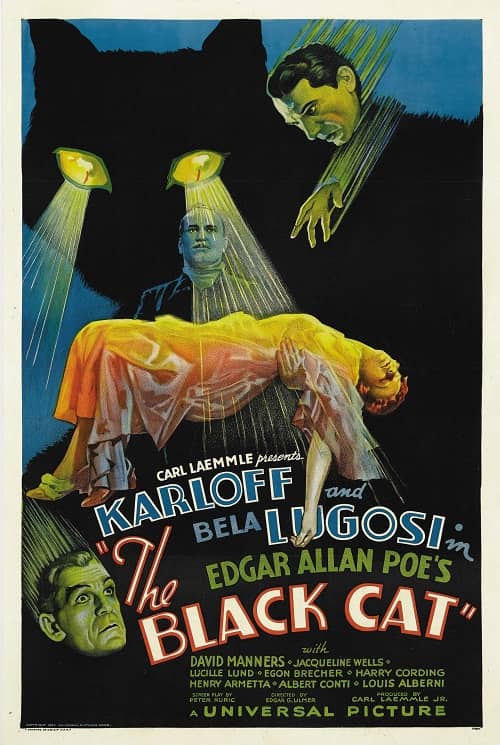

In some ways a self-destructive Al Roberts type himself, Ulmer sabotaged his promising career with the major studios when he made a movie that was too outré by far, that gothic expressionist feast of perversion, sadism, and necrophilia, the 1934 Karloff-Lugosi Black Cat. He made it while his boss, Universal Studios head Carl Laemmle, was away in Europe and it didn’t matter that it’s probably the most extraordinary horror movie of the 30’s; when Laemmle got home and saw what he’d financed, he hit the roof. And when you combine The Black Cat with the fact that Ulmer fell in love with the wife of Laemmle’s nephew and wooed her away from her husband (she divorced him and married Ulmer), it’s no mystery why a man of his talent spent his career exiled from mainstream Hollywood, doomed to forever make quickie movies for the Poverty Row studios.

The Black Cat (1934)

Edgar G. Ulmer: The Man Off-Screen chronicles all this and more, and is filled with affectionate appreciations of Ulmer’s films and reflections on the travails — and unique freedoms and opportunities — of a working life spent far from the major studios. Along the way a host of people have their say, including directors Roger Corman (who knows a few things about B Movies), Joe Dante, John Landis, Peter Bogdanovich, and Wim Wenders, and actors Ann Savage, William Schallert, John Saxon, and Peter Marshall. The whole thing is framed as a sort of Hollywood ghost story, and it’s a lovely tribute to a man who turned misfortune into art and who said, “I really am looking for absolution for all the things I had to do for money’s sake.”

For myself, I can do no better than to urge you to grant a little absolution to Ulmer’s restless spirit by seeing this dark dream from the gutter, his great and enduring film, Detour.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Like a Phoenix from the Ashes, City of Heroes Returns!

Hey! Who you calling pathetic???

You’re in good company, John. 🙂