The Iron Teacher

I try to stay away from expounding on the popular cultural artifacts from other countries. Going back in time and explaining why American pop culture looks the way it does often ranges from difficult to impossible. Even the English, a culture separated from ours by a common language, has a past that is a semiotic mystery most of the time.

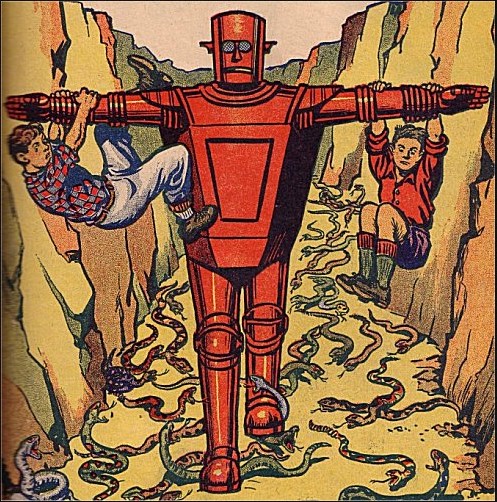

Take comic books. Americans invented them (depending on what you consider Italy’s Il Giornalino to be) and the English followed closely behind. The Dandy started in December 1937 and The Beano on July 30, 1938, meaning it will reach its 4000th issue this summer. (It’s been issued weekly except during WWII.) Both were part of the gigantic D. C. Thomson & Co. empire. By then Thompson already had a lock on the boys’ story paper market, those being the British equivalent of the boy’s story weeklies that proliferated in the U.S. during the late 19th century. (Those are now famed for introducing early robots like the Steam Man and the Electric Man, along with many other science-fictional inventions.) The story weeklies usually carried a complete short novel or a serialization of a longer one. The story papers also carried serializations, but those were short segments that appeared alongside complete short stories.

Thompson started Adventure in 1921 and added The Rover, The Wizard, The Skipper, and, in 1933, The Hotspur. (The internet tells me that the name comes from the noble warrior Sir Henry Percy, known as Sir Harry Hotspur, who is immortalized by an appearance in Shakespeare’s Henry IV. Exactly the sort of everybody-gets-it reference that trips me up when encountering other cultures.) These “Big Five” dominated the market and lasted for generations, eventually mostly being merged into one another as the market for story papers faded at the end of the 20th century.

In Keith J. Taylor’s entry

In Keith J. Taylor’s entry