Disgust and Desire: An Interview with Anna Smith Spark

It is not intuitive to seek beauty in art deemed grotesque/weird, but most authors who produce horror/fantasy actually are usually (a) serious about their craft, and (b) driven my strange muses. This interview series engages contemporary authors & artists on the theme of “Art & Beauty in Weird/Fantasy Fiction.” Previously we cornered weird fantasy authors like John Fultz, Janeen Webb, Aliya Whiteley, Richard Lee Byers, Sebastian Jones, Charles Gramlich, and Darrell Schweitzer. This one features the “Queen of Grimdark,” Anna Smith Spark.

Anna Smith Spark is the author of the critically acclaimed Queen of Grimdark. The David Gemmell Awards shortlisted The Court of Broken Knives and The Tower of Living and Dying continued the Empires of Dust trilogy (Harper Voyager US/ Orbit US/Can). The finale, The House of Sacrifice, will be published August 2019. Anna lives in London, UK. She loves grimdark and epic fantasy and historical military fiction. Anna has a BA in Classics, an MA in history and a Ph.D. in English Literature. She has previously been published in the Fortean Times and the poetry website greatworks.org. Previous jobs include petty bureaucrat, English teacher and fetish model. Anna’s favorite authors and key influences are R. Scott Bakker, Steve Erikson, M. John Harrison, Ursula Le Guin, Mary Stewart and Mary Renault. She spent several years as an obsessive D&D player. She can often be spotted at sff conventions wearing very unusual shoes.

Twitter: @queenofgrimdark / Facebook: Anna Smith Spark / Blog CourtofBrokenKnives.org

This interview will focus on her take on Beauty in Weird Fiction, but you’ll be interested in previous engagements. During the Feb 22, 2019: Fantasy Focus Podcast she discussed challenging the stereotypes of heroes and the role of good & evil in literature. She tackled politics in the real world in her Sept 17, 2018 Interview with Three Crows Magazine (long live Brexit!). In August 2017, she spoke with Rob Matheny and Philip Overby on the Grimm Tidings Podcast (part 1) and (part 2) covering the pressures of being a new author, her thoughts on the ever-evolving Grimdark sub-genre, about her struggle with dyslexia, dyspraxia, and Asperger’s Syndrome.

A) You dedicated The Court of Broken Knives to your father. Tell us more about your father’s influences. Did he read to you? Did he write?

My father is a poet. He writes, and also publishes poetry on his website greatworks.org.uk. His poetry is in the high modernist and post-modernist tradition: complex, literary, intensely personal, intensely political deconstructing language and meaning. Many of my parents’ friends are also poets, playwrights, artists, teachers: I grew up in a household saturated with language. Many of my earliest memories involve listening to my father and his friends discuss literature and art.

My father had, and continues to have, a huge impact on my writing. He shaped my love of fantasy and history as a child – he read me Tolkien, Alan Garner, Kevin Crossly-Holland, Roger Lancelyn-Green; later, he introduced me to The Wasteland, Lear, Blake, TH White, Hope Hodgson, Gene Wolfe, M John Harrison. We went on holiday in the English countryside every year and talked about the landscape and the mythologies rooted in, we went to the British Museum together and looked at the statues of ancient gods.

We’re very close still, my father is the only person who sometimes sees my writing before it goes to my editor.

B) You have Ph.D. in English Literature: what was the thesis about, and did it inspire Empires of Dust at all?

My thesis was about a Victorian occult group called the Theosophical Society, which was the forerunner of a lot of New Age belief. My key text was Madame Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine, which took elements of Hinduism, Buddhism, Hermeticism and the Kabbala, ‘rationalized’ them as Platonic allegories and rewrote them in light of (a misunderstanding of) Darwinian evolutionary theory. Kind of like The Da Vinci Code, ‘revealing the truth about human history encoded in random weird religious shit’, only a) deeply politically problematic, orientalist, structurally racist; and b) at its height tens of thousands of people believed in it. The Secret Doctrine tells the true history of mankind (sic) from the creation of the universe to our eventually future evolution into gods – imagine evolutionary theory and reincarnation mashed up together into a sort of spiritual self-improvement conveyor-belt. With totally head-f**k Lovecraftian bits like humanity’s stage as a race of sentient root vegetables. Quite a few of the leading suffragettes were members of the TS, which feminist history tends to try to ignore (can’t imagine why). My thesis was a close reading of the text trying to unpick all this and make sense of why so many people, including leading suffragettes, were attracted to it.

Madam Blavatsky herself was an amazing, terrifying figure. She presented herself in overtly orientalist terms, created an image herself as an ancient being, a grotesque high priestess. Like every misogynistic horror of female power: the witch, the hag of the ford, the crone. She was clearly a charismatic. Those around her seem to have truly believed she was in contact with other beings. She certainly abandoned her husband and children to live as an independent woman, she <may> genuinely have spent several years travelling alone in Nepal and Tibet.

My thesis didn’t directly inspire my books. But there are obvious overlaps of interest. I’ve always been fascinated by ancient history and mythology, I’ve studied western occult and magical traditions, and these things obviously come out in both my academic studies and my fiction. Blavatsky herself is there, I suspect, in elements of the novels: the way I depict the gestmet owes a lot to descriptions of the revulsion and fascination Blavatsky evoked.

C) Empires of Dust features a very poetic, almost experimental, writing style. Is this your natural voice? How deliberate was the design of the text’s structure?

A dead dragon is a very large thing. Tobias stared at it for a long time. Felt regret, almost. It was beautiful in its way. Wild. Utterly bloody wild. No wisdom in those eyes. Wild freedom and the delight in killing. An immovable force, like a mountain or a storm cloud. A death thing. A beautiful death, though. Imagine saying that to [character]’s family: he was killed fighting dragon. He was killed fighting a dragon. A dragon killed him. A dragon. Like saying he died fighting a god.

There was no conscious thought behind the first book at all. After many years of not writing, I started writing one day and a year later The Court of Broken Knives was there finished.

I write what I see in my mind. As I said above, I grew up with poetry and mythology, that poetic way of writing is a deep part of the way I see the world. And it’s what matters to me above everything. The way the words sound read aloud, how they look on the page… Sometimes I have no idea where these words are coming from, it astonishes me to see what I’ve written. But equally I’ll agonize for weeks about the precise placing of a comma or a line break.

I also suspect I’m mildly synesthesic. It’s fairly common among people who are neuraotypical. I have words that I experience as a taste when I read them, also words that trigger a sensory pleasure feeling in me. ‘Shell’. ‘Liquid’. Very weirdly, I think technical military terms like ‘a troop of horse’ and ‘advancing in echelons’ trigger a synesthesic response in me. It’s possible that the way I write is influenced by this.

D) The Court of Broken Knives replays epic, tragic history: Amrath’s bloodline (death embodied) fights the city of Sorlost (the city where life & death are balanced). What is the alluring part of Death, so much that it forms the premise of the book’s conflict?

The eroticism of war and death is something that has always fascinated me. That absolute terror of annihilation. The compulsion throughout human history to prove oneself by killing. To quote myself in The Tower of Living and Dying: ‘All men long to see dragons. Dream of wonders. Hope deep down in the depths of their souls to see wonders blaze and burn and die’. All through human history, vast armies have marched off to kill and die and gloried in it. The central paradox of The Iliad, the Tain, the Eddas: the rapturous beauty of the ruin of all things. There’s repeated reference in The Iliad to the ‘killing bronze’, ‘the black ships’, a hero as ‘manslaying.’ It’s so painfully, erotically beautiful language even as it’s utterly chilling, the language of the death cult. Go and read Male Fantasties. Then feel horror and shame.

To be more cheerful, as a good Romantic, I’m continually, morbidly sensually aware of the fierce beauty of mortality in the face of annihilation, the futility of life yet how precious it is.

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Empires, kings, lovers, poets… just dust in the wind, dude, as the great philosopher Ted Theodore Logan once said. But, as Le Guin put it in the single greatest line ever written in fantasy, to which everything else is a mere footnote: ‘I do not care what comes after; I have seen the dragons on the wind of morning.’

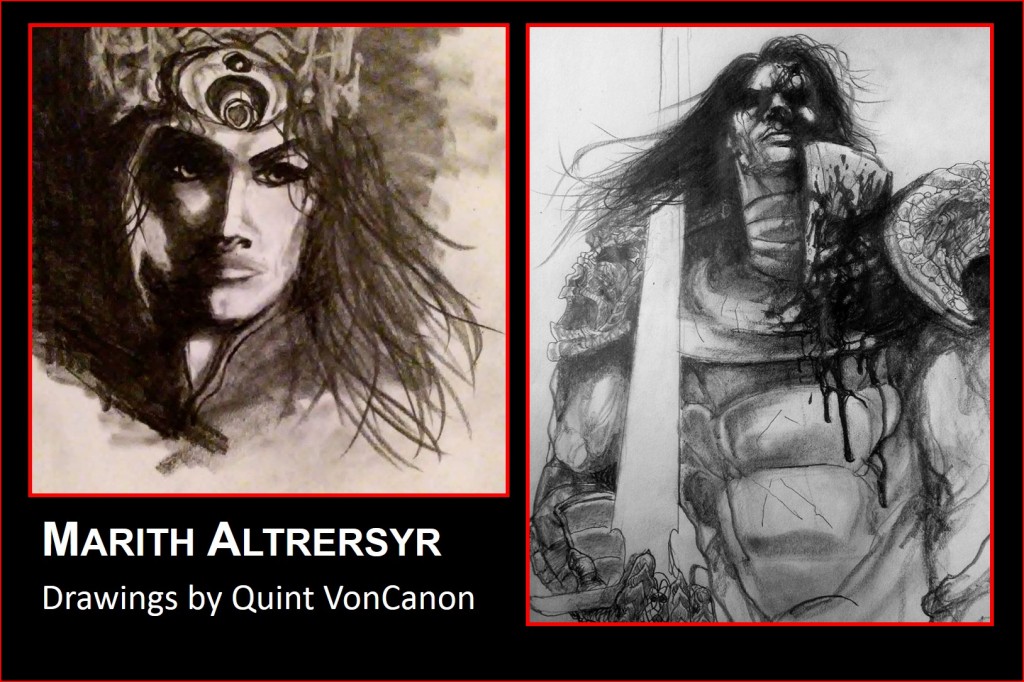

E) What resonated with me was the “Beauty in Death” theme which becomes real via Marith. Strangely most covers hide his beauty… showing only his back. Can you supply images/media-links you used to inspire your vision of Marith Altrersyr? Or is he as a monstrous, Lovecraftian beauty (i.e., too abstract to capture)? Have you ever painted or drawn him? Are there depictions of Marith Altrersyr?

Marith swerved his horse toward her. His face was rapturous. Ecstatic. So beautiful her heart leaped. He raised his sword and for a moment she thought he would kill her, and for a moment she thought she would welcome it if he did. So beautiful and perfect his face. So joyous and radiant his smile.

The language describing Marith is heavily influenced by the descriptions of Achilles in The Iliad, and by the romance that Alexander the Great then created around himself based on that.

[…] blazing like the star

that rears at harvest, flaming up in its brilliance,—

far outshining the countless stars in the night sky,

that star they call Orion’s Dog—brightest of all

but a fatal sign emblazoned on the heavens,

it brings such killing fever down on wretched men.

That’s Marith.

All-consuming beauty can never be embodied visually. What see that to me is perfect, mesmeric beauty, the apotheosis of desire … no one else will ever quite be able to see that. Like looking at someone else’s children: the mother sees perfection, total love, all their life’s meaning, dreams of hope and fears of sorrow, you see … a kid. That kind of beauty is so much a projection of the lover’s own psyche, it can’t be communicated. That’s why we fall so deeply in love with characters in books but not films, I think. We can feel desire for a beautiful character in a film, but not love them, identify with them, be haunted by own illusion of them. Marith might be plain, even ugly, to everyone else apart from Thalia. Like attempts to depict Helen of Troy. Or indeed the BBC adaptation of Wolf Hall – they can cast a beautiful woman as Anne Boleyn, give her witty lines and beautiful dresses, but what it is her that leads Henry VIII to act as he does, they can’t ever quite show that, because it’s not about her face or her body, it’s about his projection of himself onto her.

There are, however, some pictures of Marith that get alarmingly close to what I see when I write Marith. My friend Quint VonCanon drew them. They take my breath away.

F) Thalia is similar captivating. In fact, she epitomizes the “Desire and disgust” of a beautiful death dealer. Is there something you find repellent and beautiful that others may not appreciate?

She brought the knife down. Again. Again. Again. Hands not stabbing but sawing, cutting at bone and sinew, almost beyond her strength. [Her friend] screamed until she stopped screaming. Thalia stood beside her and raised her left arm. She cut herself from wrist to elbow, a shallow jagged cut over the course of her scars. The blood ran down …

In a corridor she met Tolneurn. He had been waiting perhaps. He looked at her, covered in [her friend]’s blood, her dress clinging to her body. His eye flickered. Disgust and desire. Desire and disgust.

Good and very difficult question. I have a very strong sense of disgust. I am of course massively trypophobic, feel ill just typing the word. I have a horror of insects, worms, crawling things. I also have a very good memory for things that have disgusted me, can be haunted a triggering image or the taste of something bad for weeks. I’ve got vast issues around body horror and a disgust at my physical self, had various eating disorders and all that, probably resulting from my complex feelings about my body stemming from my neuroatypicality.

The scene in Tales From Moominvalley where Little My tells the smallest whomper but one about her granny covered by fungus, and then the granny’s voice calls out from behind a door. The idea of someone alive, covered in mould, grown all over with fungus and still cheerfully talking. A thing I read once about Chernobyl, about workers sent into the reactor core covering themselves in sellotape to block the radiation. The scene in La-Bas when Giles de Rei embraces the rotting bodies of the children he’s killed, knowing what he’s done is the most terrible thing a human being can do, and the pity we feel for him. I felt so much pity for him.

G) Do you identify more with Thalia or Marith?

Probably Marith, really. He’s my animus. The absolute dark heart of me. A lot of the darkest, most self-destructive scenes in The Court of Broken Knives are drawn from my life. His parents’ response to him comes from my life too. I’ve been through some very dark periods, and that exhausted, terrified, angry response to mental illness, that desperate frustration, wanting just to scream ‘Why? Why can’t you be happy? Why do you have to do this to us?’ … I can understand, now, exactly why my parents felt that, and it seemed important to write it.

H) Do you see beauty in your own dark art?

Oh, yes. I can’t write something unless I feel it is beautiful. That’s the center of why I write. The feeling that comes when I know I’ve created something worthy of beauty. The great fantasy novelists I idolize, Bakker, M John Harrison, Le Guin, T H White, Eddison, they have that, that absolute beauty and grief.

I) Empires of Dust comes to an end this August (when House of Sacrifice releases) … can you reveal your next steps? Does the story end with this trilogy?

The story ends with The House of Sacrifice. I always had the end written. I think of Empires of Dust almost as a biography (or the hero’s journey [insert heavy irony and little speech-mark hand signals while I say that like I’m giving myself rabbit ears]). The Court of Broken Knives is the strivings of youth. Who am I am? What do I want to do with my life? The Tower of Living and Dying is full adulthood. We’ve got where we want to be so… now what? The House of Sacrifice is … the end. The board is set, the pieces are moving. We come to it at last … as some bloke who also wrote fantasy books once said.

I have various things in my head about what I want to do next, but I can’t talk about them at the moment.

I’ve written several short stories set in Irlast, for the Knaves anthology from Outland Publishing, Unfettered III from Grimoak Press, and for Grimdark magazine and Three Crows magazine; I’ve got stories coming out later this year in Legends III: Stories in Honour of David Gemmell from Newcon Press and Lost Gods from Grimbold Press. And, not in Irlast, Michael R Fletcher and I are writing a special series for Grimdark magazine. It’s called In the Shadow of Their Dying, and it’s been so much fun to write. Fletcher is good friend of mine and a brilliant writer, we’re challenging each other to see just how far we can go. Filth and disgust and total OTT gross-out.

J) You have Asperger’s, dyslexia, dyspraxia and perhaps some other mental health issues, and you have learned to leverage those to create art. Can you discuss some milestones of that inspirational journey?

I was always aware that I felt ‘different’, as a child I found it very hard to relate to other children and spent a lot of time on my own telling myself stories. (Looking back, I must have come across somewhere between Wednesday Addams and one of those Oxford dons who’s never heard of the Beatles, so it’s possibly not surprising I had some problems socializing with others my own age). Then when I was a teenager I fell apart completely. At one point it looked as though I wouldn’t be mentally well enough to take my GCSEs. I’m ashamed, now, at what I put my family through. I went through some utter hell, abusive boyfriends, all that crap. Spiraling circles of my pain and others’ pain. Marith. I stopped telling myself stories, the idea that I could write something without the gods raining down laughter on me seemed impossible. I got my life back together enough to get my PhD, get a job that paid enough to get a mortgage, fortunately. But I felt dead.

I got the dyslexia and dyspraxia (‘clumsy child syndrome,’ that kid at school who flapped when they got excited, dropped their books all the time, was picked last every week in gym) diagnosis just after I’d finished my PhD, and that explained some things. But the Asperger’s diagnosis didn’t come until my thirties, after I’d had another total mental collapse after having children. I had post-natal psychosis, in my head the best thing I could do for my baby was kill myself and have her brought up by social services.

The Asperger’s diagnosis changed everything.

I understand myself now in ways I never did. Rather than ‘why do I think I’m different? Why do I have such low esteem?’, when things get bad I can tell myself that I have Asperger’s, that the world is maybe different, maybe harder for me, and that’s just who I am, and that’s okay.

I don’t think Asperger’s is a ‘gift’, I don’t think it’s a ‘superpower’, it certainly doesn’t make me ‘better’ or ‘more interesting’. It’s a rope round my neck, often, I’m pretty useless at managing in an office, I’m not likely ever to get promoted beyond office junior, I quarrel with my family all the time about insanely stupid things, I can’t drive, I’m still always falling over my shoelaces and dropping everything. But it’s who I am, it probably does have some relationship to my writing, I am not ‘proud’ of being Asperger’s but I’m certainly not ashamed. I would never wish it away.

Depression, however, is a disease that poisoned my life and the lives of all those around me. There’s a romantic attraction to the fucked-up doomed creative. But depression wreaks creativity. More importantly, depression wreaks friendships and marriages and all this other boring normal life things. Depression is not beautiful.

K) Grimdark challenges history tropes of good and evil (black and white), and you challenge readers to empathize with antagonists/villains and despise protagonist/heroes. Any tips on how to create characters that are very gray but still interesting?

Write real people. Write about complicated, infuriating, messed-up, muddled-up, multi-layered, blind to themselves people.

To be honest, the biggest tip I can give is the very old ‘read a lot’. Get into the head of other people in all their complexity, leading lives very different to your own, thinking in different ways. I read a lot of history and historical biography, which certainly shows people in their myriad shades of grey. War diaries and eyewitness accounts are especially important. It’s so easy to see historical events in terms of good and bad, or not to think about the feelings of the people actually involved. Reading accounts of soldiers’ lives from both sides of a conflict gives such a deep sense of shared humanity. Accounts of life as a German soldier in WWII, for example. Accounts written by people fighting for something that cannot be seen as anything other than abhorrent. But people, trying to stay alive, with families and friends they love. Not the ranting vomit of sociopaths. Normal people, no different to any of us. Aware or somehow keeping themselves unaware that they are involved in terrible things. Then think about yourself, your own motives for the things you do. The bad things and the good things.

The trope of good versus evil is incredibly dangerous because it stops us needing to think about how other people might feel, what their motivations for behavior we dislike might be. Breaking down those tropes and thinking about people as basically just people is a radically important political thing.

L) More broadly, any tips on how to create art that is “dark” yet “attractive” enough to read?

Oh, goodness. I mean… some people hate my books. Completely hate them. Too dark, too bleak, unreadably violent, too horrible. That’s fine. Different books are for different people. It’s impossible to write a book that pleases everyone.

Literary quality is important, obviously. A beautifully written, complex ‘dark’ book will stand, a badly written one won’t. Das Boot is in places virtually unwatchable. Huysman’s La-Bas is disgusting. Zola’s L’Assommoir almost broke me mentally. But they stay in the mind, compulsive, gripping, impossible to look away from, because they are all in their own way so very good, so beautiful. King Lear and The Trojan Women are both chilling, horrible, bleak beyond bleak, and also probably the two greatest things every written in any language, towering, unmatchable masterpieces of language.

Complexity, also – all of the above are far more than just good versus bad. They make you think deeply about what you’re engaging with, question yourself. All those shades of grey, again.

And humor, moments of light, moments of joy. Not just to sharpen the pathos (although that, too – ‘horrible ugly people do horrible ugly things in a horrible ugly place’ isn’t a great sales pitch), but because life is too complex just to be ‘dark.’ The worst moments of my life, the most terrible moments of pain – there were still moments of happiness, of seeing something beautiful. A single flower in bloom, the smell of the earth after rainfall. The taste of a good cup of coffee, a stupid joke, a minging but curiously morish cheese feast pizza, for gods’ sake. Even in war, in suffering, in the shadow of the valley of death, there are moments of good things.

One of the things that makes Shakespeare unarguably the greatest dramatist in western literature is his delight in a good knob joke even when the night is at its darkest.

M) My favorite grimdark author Clark Ashton Smith (alive before the genre awoke) was a poet, illustrator, and sculptor; many others interviewed by S.E. have other artistic talents beyond writing. If so can we share them (i.e., images of fine or graphic art) or mp3s (of music). If not, which artists/pieces inspire you to write?

I can neither draw nor make music. I sing like a cat being strangled. Beauty and repulsion without the beauty.

A huge jumble of art and music has influenced me over the years.

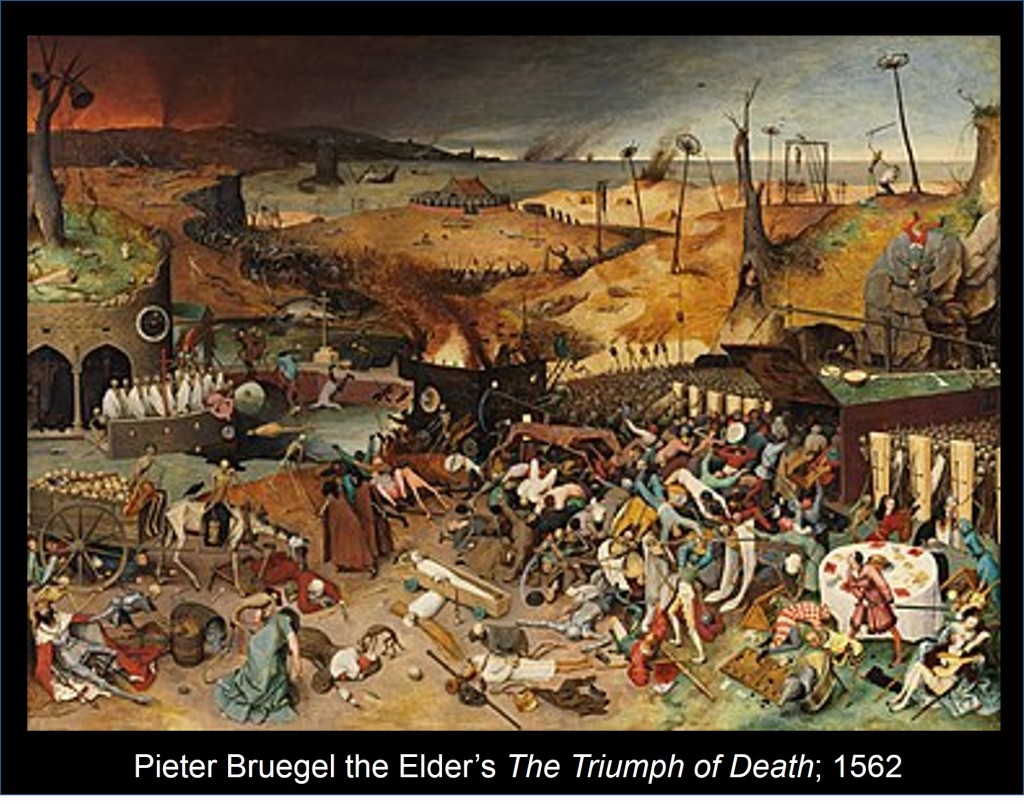

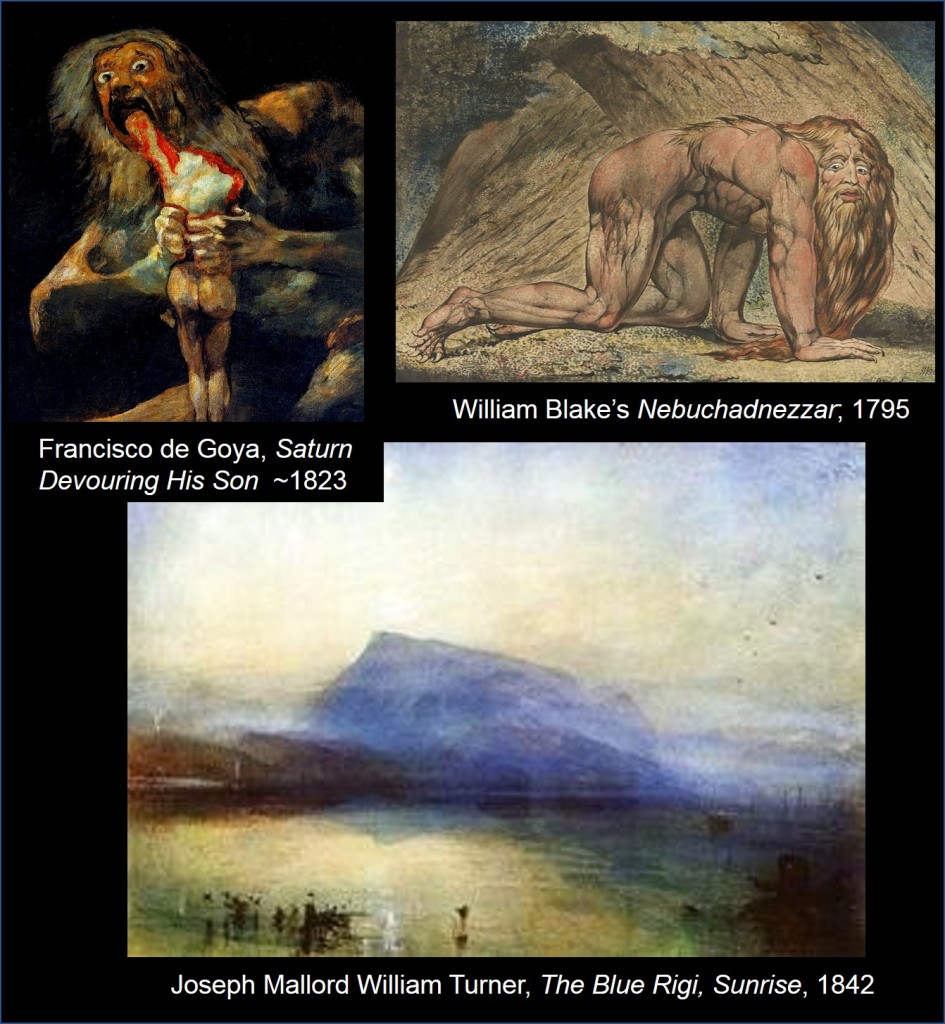

Art: Brugel’s The Triumph of Death; Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar; Goya’s Black Paintings; Schiele; Turner.

Music: Industrial folk, folk folk, goth, Leonard Cohen, The Three Penny Opera, Philip Glass, In The Nursery’s musical setting of Flecker’s Samarkand.

You can find playlists that inspired/evoke the novels on my Court of Broken Knives blog.

N) You seem to have a shoe fetish — which convention goers may witness. Any images of your feet we can share, and explanations?

The shoes thing! I love my shoes, yes. Shoes make me very happy. It’s become a bit of an albatross, now, though, because people expect to see more and more outrageous shoes when I’m at cons.

I have literally no idea how I’m going to top [the dragon shoes].

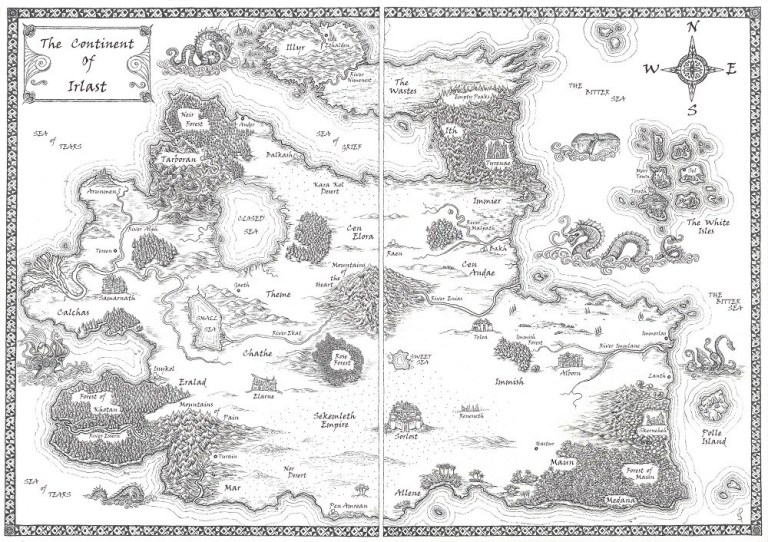

O) The world of Irast: Sophie E Tallis prepared the map for Empires of Dust. Can you describe how you partnered to create this?

When I wrote The Court of Broken Knives I didn’t have any physical map of Irlast. I didn’t world-build at all, the world just sort of unfolded itself to me, like I was really travelling through it, as I wrote. I could see the world in my head, I knew where places were, slowly I began to learn more about the history of different places in the world. The world of Irlast is a part of my subconscious, it’s formed from my deepest interests and loves. Discovering more about this world I was creating, just wallowing in exploring it, was a huge part of the writing for me. It doesn’t make coherent sense as a ‘real’ world, because of the way it emerged it’s not placed in any one period, in the same way that a lot of folklore or pre-modern historical writing is. Timelessly mythic / a hodgepodge of all my favourite historical periods flung together with no attempt to paper over the cracks.

At the end, when I decided I needed a map because all the best books have maps, I was lucky enough to know Sophie. She’s incredibly talented. I drew up a hilarious ‘cubist’ map of Irlast based on the mental map in my head, squares shaded in green for forest, yellow for desert, blue for lakes, and wrote up descriptions of the different cities. Sophie took that and created the map. (As it’s got sea all round it, she asked me if I wanted sea beasts round the edge and I was hardly going to say no.)

For The Tower of Living and Dying and The House of Sacrifice, I was then following the action on the map as it unfolded, like tracing Alexander’s route on a map of Asia. So IP could see the terrain different people were inhabiting, the difficulties they might encounter, the landscapes they would see. One of my favorite television programs is Michael Wood’s In the Footsteps of Alexander, and I was doing what Wood did there, tracing Marith’s footsteps on my map.

Bonus add on…this just in. Gencon attendees going to the Writer’s Workshop, you’ll get a live version of this at Aug 2nd; Fri 5pm, Q&A with Anna Smith Spark! See you then in Indianapolis.

Sounds great Seth!