The Storyteller’s Voice: Basil Rathbone Reads Edgar Allan Poe

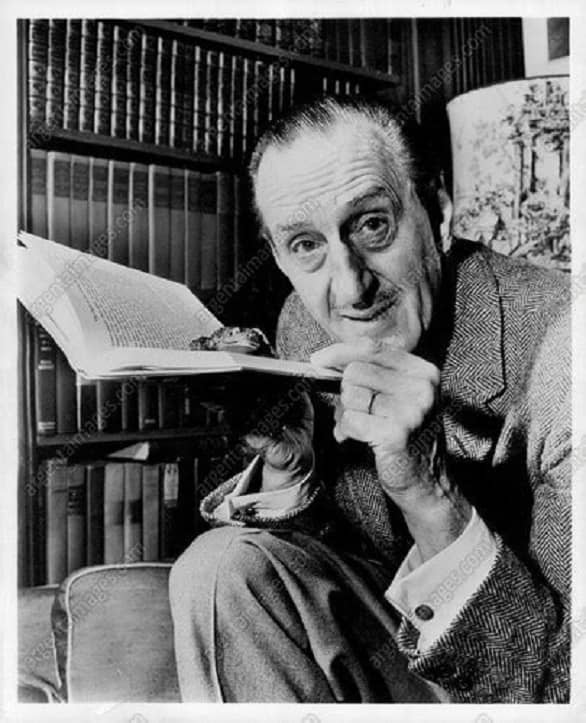

Basil Rathbone

If I say the name Basil Rathbone, I have a very good chance of guessing exactly what you’ll think (if you’re old enough, that is — if you’re below a certain age, you may only think, “Who?”); ten will get you twenty you’ll think “Sherlock Holmes,” the character that Rathbone indelibly portrayed in fourteen films from 1939 to 1946, so successfully that for many people his name has become synonymous with the character.

And if by some chance you don’t think of Holmes, you’ll almost certainly think of the greatest swordsman in Hollywood, the piercing-eyed, hawk-visaged athlete who figured in some of the screen’s most thrilling duels, most famously against John Barrymore and Leslie Howard in Romeo and Juliet (1936), Errol Flynn in Captain Blood (1935) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), and Tyrone Power in The Mark of Zorro (1940), the latter battle the most exciting swordfight in movie history, in my opinion.

In addition to these swashbuckling villains, in his almost fifty year film career Rathbone applied his singular talents to bringing many other characters to vivid life. Some of his most memorable non-action roles are his icily sadistic Mr. Murdstone in David Copperfield, his brutally indifferent Marquis St. Evrémonde in A Tale of Two Cities, his rigid, fatally conventional Alexi Karenin in Anna Karenina (all in 1935 — studio era Hollywood worked its players hard), and his witty, cynical Richard III in Tower of London (1939), with Vincent Price as his brother Clarence and Boris Karloff as his murderous, club-footed henchman, Mord; truly, they don’t make ’em like that anymore!

Rathbone and Power in The Mark of Zorro

In his prime years, Rathbone was a striking physical presence; tall and virile, with deep-set, icy blue eyes and an aquiline profile, his sharp good looks had more than a hint of cruelty about them, and when you combine his arresting appearance with a brisk, dominating manner that suggested a tightly coiled steel spring, he was more than able to hold his own in any scene, even when sharing the screen with the biggest stars in the business.

But distinctive as his looks were, Rathbone’s greatest asset may have been his voice. It was the perfect compliment to his appearance; hard yet flexible, razor-edged and rapid in delivery as his sword thrusts, the actor’s voice was an ideal instrument for that form of deadly combat known as polite conversation, especially as it was waged in the studio-manufactured castle keeps and drawing rooms of Warner Brothers and Twentieth Century Fox.

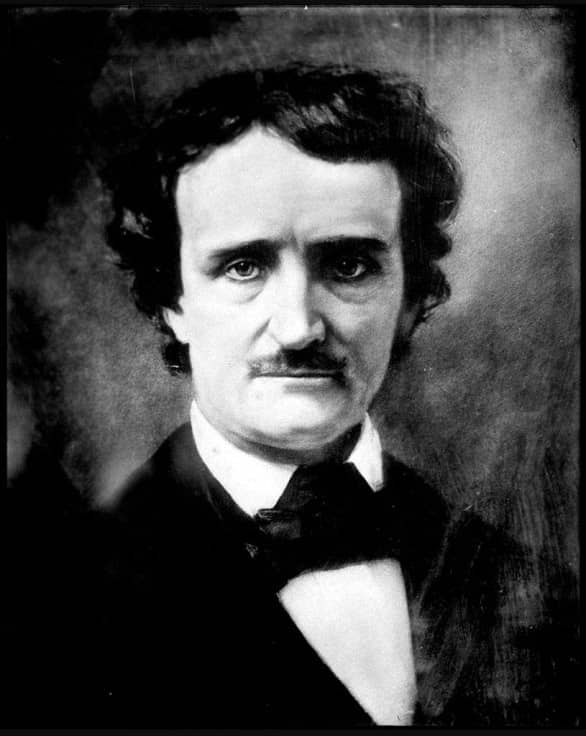

Edgar Allan Poe

But all things must end, and as the thirties, forties, and fifties all slipped into the past, the Golden Age of Hollywood went with them and roles for a man of Rathbone’s talents grew fewer and fewer. In any case, by the end of that period Rathbone (who was born in 1892) likely wouldn’t have had quite enough energy to go rushing up and down stone staircases swinging a sword over his head even if the opportunity had offered itself — though he was still able to manage a nice comic swordfight with Danny Kaye in 1955’s The Court Jester.

This meant that by the end of the fifties, Rathbone, now approaching seventy, was relegated mostly to work in increasingly inferior movies and guest appearances on television shows. But even though the swashbucklers and costume movies that made him an icon had faded into Hollywood history, Rathbone’s distinctive voice remained almost undiminished, and he used it to produce his last distinguished work, a series of three record albums on which he read some of the greatest poems and stories of Edgar Allan Poe.

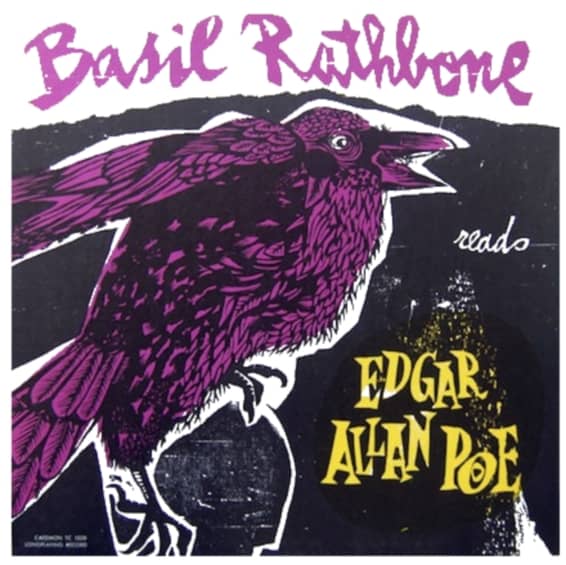

Basil Rathbone Reads Edgar Allan Poe, Volume One

The albums — all titled Basil Rathbone Reads Edgar Allan Poe — were produced by Caedmon Records, a pioneer in the field of spoken word recordings. In the first volume, which appeared in 1957, Rathbone reads “The Raven,” “Annabel Lee,” “Eldorado,” “To…,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” “Alone,” “The City in the Sea,” and “The Black Cat.”

In 1960 there was a second volume which included “The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” and “The Pit and the Pendulum.”

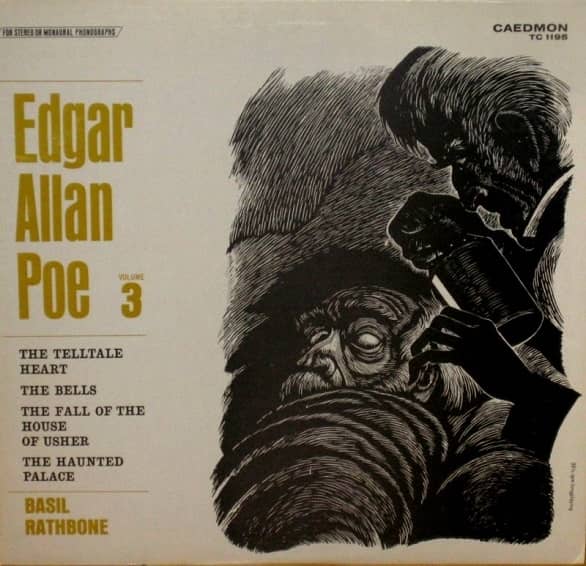

The third and final volume came out in 1965 and contains renderings of “The Telltale Heart,” “The Bells,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and “The Haunted Palace.”

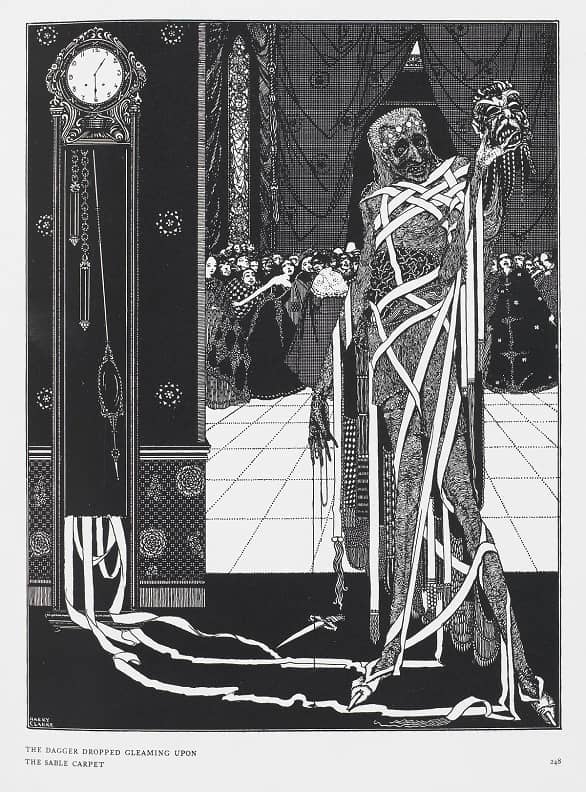

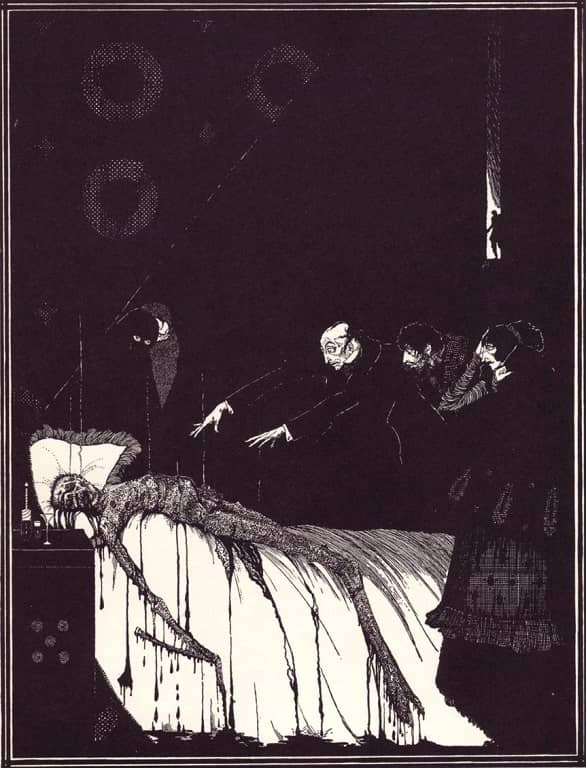

The Masque of the Red Death by Harry Clarke

Basil Rathbone was an ideal interpreter for this material; he was made to give voice to Poe’s histrionic, solipsistic narrators. There isn’t a weak effort on any of the three recordings, but on the first disc, he does especially well with the chill ironies of “The Masque of the Red Death.” Rathbone sounds as if he is the eternal voice of Time itself, looking contemptuously down at the ridiculous blindness and self-regard of human beings and sardonically rendering its verdict on the hedonistic follies of the self-deceiving Prince Prospero and his doomed guests. Rathbone’s rendition of the story’s last lines,

And the life of ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all

falls on the ear like the grim, irrevocable sentence of a hanging judge or like the final despairing beats of an expiring heart. Like the rest of his reading, it is simply superb.

Volume Two

The highlight of the second record is “The Cask of Amontillado,” which unlike either of the tales in the first volume, allows Rathbone to display his skill with dialogue in the exchanges between the murderous Montressor and his victim Fortunato. He perfectly conveys the cunning that allows Montressor to conceal his obsessive hatred beneath a veneer of ironic politeness, and his vain, peevish Fortunato is a delight. You can practically see the fool squinting and stumbling through the shadowy vaults of the Montressors as his muddled mind gropes its way through an alcoholic fog, a fog the dupe will emerge from only when he finds himself chained in his tomb. When the suddenly sobered Fortunato realizes that he has been lured into his own grave, the screams that emerge from his throat are shocking and truly terrifying.

M. Valdemar by Harry Clarke

Just as good is “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.” When you hear Rathbone’s rendition of the voice of Valdemar, held by hypnosis in a horrible state between life and death, your blood temperature will drop by at least twenty degrees. Poe describes it as

a voice — such as it would be madness in me to attempt describing… the sound was harsh, and broken, and hollow; but the hideous whole is indescribable, for the simple reason that no similar sounds have ever jarred upon the ear of humanity.

Amazingly, Rathbone does not disappoint, even after such a build-up; he manages to perfectly, chillingly convey the “vast distance” and the “gelatinous or glutinous” quality that Poe attributes to the unearthly sound that issues from Valdemar’s throat. When the narrator asks Valdemar if he is still sleeping and he replies in a hideous tone that is half rasping croak, half agonized whisper, “Yes; — no; — I have been sleeping — and now — now — I am dead,” if your flesh doesn’t feel as it’s going to crawl off your bones and go hide under the bed, then you’ll know that you’re the one who’s passed away.

Volume Three

On the final album, Rathbone’s masterful reading of “The Tell-Tale Heart” particularly stands out. As soon as he speaks the first line, “True! — nervous — very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad?” in a clipped, rapid voice that can scarcely suppress a quaver, you know that this chap has left ordinary, mere garden variety insanity far behind. His fussy pride in his preparations for his crime, the bloody murder itself, and the mounting frenzy that ends in his uncoerced confession are all conveyed with the virtuosity befitting a great actor.

In all of these poems and stories, Rathbone isn’t afraid of the emotional high notes (highs that often soar into outright hysteria), and he hits them unerringly. He knows that Poe isn’t writing real estate prospectuses or greeting cards; he’s giving us his own unique literary blend of Grand Guignol and grand opera.

Rathbone, Price, and Poe

The best news is that, old as they are, all three albums can be had from Amazon, combined with Vincent Price’s readings of several more Poe stories (“The Imp of the Perverse,” “Morella,” “Ligeia,” “Berenice,” and “The Gold Bug,” all of which Price had done on Cademon albums of his own) under the title Basil Rathbone and Vincent Price Read Edgar Allan Poe Stories & Poems. (If the title alone doesn’t get your pulse racing, come sit over here — we need to have a talk. I’ll just manacle you to the wall so we won’t be disturbed. You can sit on that pile of bricks…what are they for? Don’t worry about it.) If you have Amazon Prime you can stream the whole thing for free; it’s also available as an MP3 album for less than ten dollars — the bargain of the century, I’d say. Or, if you prefer, every track from all three Rathbone albums can be heard on YouTube.

The Storyteller

However you choose to listen to these magnificent interpretations of Poe’s tormented masterpieces, do it. Lock the doors, put away the phone, turn down the lights, and just listen. Leave the already dying present moment behind and surrender yourself to the timeless, to what those who came before us knew was the greatest, most powerful entertainment medium ever devised — the voice of a master storyteller, coming to you out of the dark.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us asked Will the Real Captain Marvel Please Stand Up, or Why Can’t the World’s Mightiest Mortal Use His Own Name?

A Basil Rathbone post. Woohoo!!

And yes, I’m one of those that sees Sherlock Holmes, as I wrote about here at Black Gate.

And some Christmas, I’m FINALLY gonna get around to writing a post here about the excellent dark Christmas comedy, ‘We’re No Angels.’

NOT that insipid DeNiro/Penn remake: the Bogart/Rathbone/Ray version.

Not to pull focus, but I don’t know if anything can top William S. Burroughs reading “Masque of the Red Death”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ko0El5pOZGY

I’m not familiar with that, Adrian. I definitely will give it a listen. The great Sydney Greenstreet also did a very fine rendition of the Cask of Amontillado, but I’ve been unable to find it online anywhere to share.

Thank you Mr. Parker, for paying tribute to a great actor, a magnificent swordsman and a soldier who fought for his country at the sharp end of the spear in World War I. (He conducted daylight recon of enemy positions.)

Rathbone’s former home was burned down by an arsonist, recently.

Also, his swordfight in “The Court Jester” is a work of genius! I mean, anybody can do a straight up swordfight, but a swordfight against an opponent alternates between a master fencer and a panicked (although inspired) amateur– that’s a feat!

Rathbone’s autobiography, In and Out of Character, is one of the best books of its sort I’ve ever read. Well worth seeking out if you’re interested in the man or in Golden Age Hollywood.