The Lost Literature of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The New Shadow”

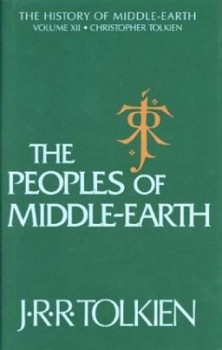

Recently, game submissions opened for Coulee Con, a local gaming convention that takes place over one weekend every August. This year I’m offering a scenario based on Tolkien’s “The New Shadow,” which is an aborted sequel to The Lord of the Rings. Christopher Tolkien collected the fragment in 1996’s The Peoples of Middle-Earth.

Recently, game submissions opened for Coulee Con, a local gaming convention that takes place over one weekend every August. This year I’m offering a scenario based on Tolkien’s “The New Shadow,” which is an aborted sequel to The Lord of the Rings. Christopher Tolkien collected the fragment in 1996’s The Peoples of Middle-Earth.

It’s an interesting piece, obviously, not least because it was intended to become another book set in Middle-earth — a book from no less than the great Tolkien himself! The snippet is maddeningly short, however. Perhaps its brevity results from a malformed conception that precluded it from ever actually becoming anything. This is overstating my view: rather, I believe that Tolkien’s “New Shadow” promises to have been an immensely profound articulation, but (as The Silmarillion that Christopher Tolkien published after his father’s death, to an ambivalent reception from Middle-earth enthusiasts) it likely would have been so different a book from The Lord of the Rings as to be misunderstood by its waiting audience.

I think it’s important to establish that Tolkien was a practitioner of many genres. He earned his living as an academic and therefore published many critical essays. The two most valuable to us fantasy enthusiasts now are “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” and “On Fairy Stories.” As a philologist he translated many epic poems into modern English; the two most visible to us are Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. He practiced poetry himself: many of Middle-earth’s early legends first were conceived in verse; he wrote the epic The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun; obviously we must mention the many songs and poems in The Lord of the Rings itself. He wrote satirical comedy in “Farmer Giles of Ham,” faerie romance in “Smith of Wootton Major.” Most importantly, he wrote in the long folk/fairy tale mode with The Hobbit, the epic novel with The Lord of the Rings, and Classical epic with The Silmarillion — a terse, condensed style that, in my youth, had me telling my friends that it was the Bible of Middle-earth.

I have heard friends joke about The Silmarillion as the bestselling book that no one ever read (for the record, I have read it many times, of course). I don’t think that “The New Shadow” would have had the same reception, though the attention given it certainly would have been ambivalent. This is because a new book from Tolkien would have occasioned yet one more genre from him. This time, it would have been a thriller.

It would appear that Tolkien abandoned this project precisely because of misgivings concerning this particular genre. In Peoples, Christopher Tolkien cites a 1964 letter of Tolkien’s. Tolkien writes of “The New Shadow,” “I could have written a ‘thriller’ about the plot [about a Satanic, Orc-cult] and its discovery and overthrow — but it would be just that. Not worth doing.”

It would appear that Tolkien abandoned this project precisely because of misgivings concerning this particular genre. In Peoples, Christopher Tolkien cites a 1964 letter of Tolkien’s. Tolkien writes of “The New Shadow,” “I could have written a ‘thriller’ about the plot [about a Satanic, Orc-cult] and its discovery and overthrow — but it would be just that. Not worth doing.”

But would it have been “not worth doing?” Not likely. By the same lights, The Lord of the Rings could have been abandoned as just another quest narrative about the finding and destruction of an object and the overthrow of a tyrannical villain. But it’s more than that, obviously, so much so that numerous books now have been written on both Tolkien and his work. I must add that much of the academic criticism is interested in what Tolkien’s work means, not merely in what Tolkien is as a popular sensation. Tolkien’s work highlights ecological concerns, the nature of evil and human friendship, and many other themes. In other words, it is literature; it can be read many times, and, with every read, the thinker again will learn something about life, nature and reality. The same, I believe, would have been said of “The New Shadow.”

The fragment begins in Pen-arduin, a suburb of Minas Tirith — indeed, the towers of the White City are descried across the waves of the Anduin River, upon whose banks the town is built. Our perspective character, Borlas, who once served as “the first Captain of the Guard of Prince Faramir,” says aloud one eventide in his garden in June, “Deep indeed run the roots of Evil.”

This begins an argument with Saelon, a childhood friend of Borlas’s absent son Berelach. It appears that Saelon is rankled — still — for Borlas once describing Saelon’s childhood antics as “Orcs’ work.” Borlas caught Saelon as a child picking unripe apples out of Borlas’s orchard — merely to play with. This is why Borlas categorized the behavior with such condemnation, for it is right, natural and respectful to allow the fruit to ripen for the good use of Men, or, as Borlas says, “to misuse [fruit] unripe… robs the world, hinders a good thing from fulfillment,” and Saelon, though young at the time, in Borlas’s estimation was old enough to understand this. But from here Saelon rushes through a series of precepts to what appears to be a prepared conclusion. I shall try to summarize the argument.

Saelon “would not misuse green fruit now,” but only because, now as an adult, he doesn’t have need of this kind of use. In other words, a child has uses for unripe fruit (such as throwing them at their friends) that adults might not have, but just because they are children doesn’t mean that they are conducting “Orc-work” or behaving “unnaturally.” Saelon then claims that, to trees, all Men must be Orcs, who cut down trees. (This is a clear case of redirection, or a “but-what-about-ism.”)

But Borlas doesn’t fall for it: “A man… who tends a tree and guards it from blights and many other enemies does not act like an Orc… If he eats its fruit, he does it no injury. It produces fruit more abundantly than it needs for its own purpose: the continuing of its kind.”

But Borlas doesn’t fall for it: “A man… who tends a tree and guards it from blights and many other enemies does not act like an Orc… If he eats its fruit, he does it no injury. It produces fruit more abundantly than it needs for its own purpose: the continuing of its kind.”

Saelon carries on with his redirection, though: the cutting down of trees. To this Borlas gives an answer in perfect concordance with Christian Catholic orthodoxy, though obviously it is couched within the mythos of Middle-earth:

[T]rees are not judges. The children of the One are the masters… The evils of the world were not at first in the great Theme, but entered with the discords of Melkor. Men did not come with these discords; they entered afterwards as a new thing direct from Eru, the One, and therefore they are called His children, and all that was in the Theme they have, for their own good, the right to use — rightly, without pride or wantonness, but with reverence.

To return to chopping down trees, Borlas teaches that the action is right if warmth is needed, but the woodman “must not mar the tree in play or spite, rip its bark or break its branches. And the good husbandman will use first, if he can, dead wood or an old tree; he will not fell a young tree and leave it to rot, for no better reason than his pleasure in axe-play. That is orkish.”

Here Saelon appears to give up the argument for the authorial introduction of the plot, the “thriller.” But before continuing on with this, we must go back to the beginning of the discourse, because this work is not a simple fantasy of “Borlas is ‘right’ and Saelon is ‘wrong.’” No, this is literature, and there is more to learn.

If there is a rising Orc-cult, and if Saelon is a part of it, then he accuses Borlas of driving him there: “Orcs’ work! I was angered by that, Master Borlas, and too proud to answer, though it was in my heart to say in child’s words: ‘If it was wrong for a boy to steal an apple to eat, then it is wrong to steal one to play with. But not more wrong. Don’t speak to me of Orcs’ work, or I may show you some!’” This is a too typical childish response to correction. Someone who is accused of doing wrong desires to do yet more wrong — or even greater mischief — out of misplaced pride and a shameful need for revenge.

And now Saelon claims that Borlas’s use of the word “Orc” at that time made Saelon more interested in what Orcs might actually be:

You turned my mind to them. I grew out of petty thefts … but I did not forget the Orcs. I began to feel hatred and think of the sweetness of revenge. We played at Orcs, I and my friends, and sometimes I thought: ‘Shall I gather my band and go and cut down trees? Then he will think that the Orcs have really returned.’

Again Saelon is redirecting, but this time there is some validity to it. Saelon seems to be revealing the paradox in human nature and interaction that necessitates that “wrong” be exposed and corrected, but, at the same time, this very act of censure risks piquing the culprit to greater outrages while simultaneously promising knowledge of yet deeper sin. This would not be news to either St. Paul or Michel Foucault. St. Paul writes that awareness of the Law causes sin to enter into the cosmos. Foucalt claims that every positive declaration must by extension simultaneously contain its negation. In other words, knowledge of the good likewise begets evil.

Again Saelon is redirecting, but this time there is some validity to it. Saelon seems to be revealing the paradox in human nature and interaction that necessitates that “wrong” be exposed and corrected, but, at the same time, this very act of censure risks piquing the culprit to greater outrages while simultaneously promising knowledge of yet deeper sin. This would not be news to either St. Paul or Michel Foucault. St. Paul writes that awareness of the Law causes sin to enter into the cosmos. Foucalt claims that every positive declaration must by extension simultaneously contain its negation. In other words, knowledge of the good likewise begets evil.

So what can the good person do here? Must that person ignore wrong in the fear of begetting greater wrong, never correct a child, never in fact teach? Borlas recognizes his culpability and, perhaps, a fatalism contingent to the realities of human nature:

Alas… we all make mistakes. I do not claim wisdom, young man, except maybe the little that one may glean with the passing of years. From which I know well enough the sad truth that those who mean well may do more harm than those who let things be. I am sorry now for what I said, if it roused hate in your heart. Though I still think that it was just: untimely maybe, and yet true.

For the purpose of this analysis, I have parsed out these elements, but the text commingles them. In the argument, Borlas has the right of it, but he may have behaved in error — or Saelon’s sympathies, whatever they might be, might be determined, (as St. Paul might also say) like “vessels of wrath fitted unto destruction,” simply because of awareness of the Law. Also, the argument isn’t about reason alone, but Saelon clearly has some emotional currency at stake.

I could rest my case for literary merit right here, but there’s more. If I take you back to the beginning of the fragment, I can remind you that Borlas arrestingly — and alarmingly — compares Evil to a tree: “Deep indeed run the roots of Evil… and the black sap is strong in them. That tree will never be slain. Let men hew it as often as they may, it will thrust up shoots again as soon as they turn aside.” And these esoteric words: “Not even at the Feast of Felling should the axe be hung up on the wall!”

I must note that this is how the whole argument begins, with figurative language of an Evil tree, with unending and vain violence being done to it. It might refer to the passing of the previous Evil — Sauron — at the culmination of the War of the Ring, and how that Evil might spring up again. Sauron likewise was begot of his master Morgoth. But it also might presage how the axe that Borlas brought to Saelon’s misdeed results in yet more prodigal tendrils through Saelon’s now incited interest in Orc-work. It certainly must originate from Tolkien’s personal Catholic vision of the task of Good versus Evil never finding resolution, not till the end of time. And it is most compelling that Tolkien chooses the image of a tree, something that is wholly good (at least within the resulting argument) and entirely natural. This suggests (to glide the metaphor back to its referent) that humanity is inextricably bound up good with evil, that one never will entirely eradicate the other. If this is the theme, and if Borlas and Saelon lay out the argument, then it is a grand theme indeed and one uniquely appropriate as a follow up to The Lord of the Rings.

At this point it is worthwhile to again look at Tolkien’s reasons for abandoning this potential sequel. In the same letter of 1964, Tolkien writes, “I did begin a story placed about 100 years after the Downfall, but it proved both sinister and depressing. Since we are dealing with Men it is inevitable that we should be concerned with the most regrettable feature of their nature: their quick satiety with good.” It would appear that Tolkien was unwilling to spend his later years with natural Men, people who grow bored with Paradise and Right and whose truly good members cease their vigilance as watchmen — in other words, people who become complacent with ease. Moreover, the absolutism between Good and Evil that critics sometimes take issue with in Tolkien’s masterpiece here would become confused and blended, simply because Evil no longer could be personified as a single person (Sauron or Morgoth) but most likely would take shape as feelers inhabiting and manipulating misguided and pitiable people. Indeed, it would have been a new mode for Tolkien, much diminished — but no less momentous — from the dualistic epic of The Lord of the Rings. This is no better exemplified in “The New Shadow” than when Borlas asks Saelon if he belongs to this new cult. Before answering, Saelon responds with the like question:

At this point it is worthwhile to again look at Tolkien’s reasons for abandoning this potential sequel. In the same letter of 1964, Tolkien writes, “I did begin a story placed about 100 years after the Downfall, but it proved both sinister and depressing. Since we are dealing with Men it is inevitable that we should be concerned with the most regrettable feature of their nature: their quick satiety with good.” It would appear that Tolkien was unwilling to spend his later years with natural Men, people who grow bored with Paradise and Right and whose truly good members cease their vigilance as watchmen — in other words, people who become complacent with ease. Moreover, the absolutism between Good and Evil that critics sometimes take issue with in Tolkien’s masterpiece here would become confused and blended, simply because Evil no longer could be personified as a single person (Sauron or Morgoth) but most likely would take shape as feelers inhabiting and manipulating misguided and pitiable people. Indeed, it would have been a new mode for Tolkien, much diminished — but no less momentous — from the dualistic epic of The Lord of the Rings. This is no better exemplified in “The New Shadow” than when Borlas asks Saelon if he belongs to this new cult. Before answering, Saelon responds with the like question:

“How can you think it?” cried Borlas.

“And how can you think it?” asked Saelon.

And so it goes: Good questions after Evil, and Evil insinuates that that act itself is a product of Evil. Evil sophistry and misdirection keeps the Good self-reflecting and mired in mistrust and accusation.

With all the time I’ve spent on the argument and theme, you might be struggling to find the “thrill.” Oh, it’s here. After suddenly abandoning the debate, Saelon invites Borlas to a nighttime tryst. But Borlas must dress all in black; this appears to be a requirement of the members of the secret cult. There have been whispers of the secret name of Herumor, the name of a lieutenant of Sauron in the South during the War. Dunadan ships have mysteriously been lost at sea. Borlas himself hasn’t seen his son (who is with the Dunadan navy) for some time, and the reader wonders what news Berelach might bring, if he isn’t also lost.

Borlas — an aging man outside his time — might be our hero. Or he might not. He might have no other purpose but to set up the argument and the tone before — in true thriller fashion — being slain by a villain. He resolves to join Saelon in the tryst, alike uncertain of Saelon’s own motives and whether it’s an ambush. He decides, “Perhaps I have been preserved so long for this purpose: that one should still live, hale in mind, who remembers what went before the Great Peace. Scent has a long memory. I think I could still smell the old Evil, and know it for what it is.”

It seems that Tolkien didn’t wholly abandon his sequel. If he had had another lifetime, he might have completed it, through his usual method like waves crashing, one after the other, up a beach at high tide. In 1972 he wrote a new version of the opening, though he abandoned it again, with a letter almost precisely like that of 1964, but this time to a new recipient.

After his talk with Saelon, Borlas turns to home:

The door under the porch was open; but the house behind was darkling. There seemed none of the accustomed sounds of evening, only a soft silence, a dead silence. He entered, wondering a little. He called, but there was no answer. He halted in the narrow passage that ran through the house, and it seemed that he was wrapped in a blackness: not a glimmer of twilight of the world outside remained there. Suddenly he smelt it, or so it seemed, though it came as it were from within outwards to the sense: he smelt the old Evil and knew it for what it was.

So should we all.

Gabe Dybing’s last article for us was an interview with the creators of Sagas of Midgard.

Remember that short story by Tim Pratt, in which the protagonist wanders into a video store that has appeared from an alternate reality through some temporary temporal displacement? He is able to check out films that were never made here, that only exist in that other world, and to see films that came out differently (perhaps starring different actors or with different endings).

If I ever stumble into a bookstore that stocks such alternate books that never were written (and isn’t that also the case with the Library of Ankh-Morpork?), the first title I’d hunt for is The New Shadow by J.R.R. Tolkien.

Nick, I think what you’re looking for is Lucien’s library in the Dreaming in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman.

What an interesting post this is.

One element that might work into the story, had it been written, could have been the departure of the Elves from Middle-earth and the “fading” of those who remain. It could be that, in *some* way, this would factor into the Orc-cult business, if we take it that the Orcs were somehow derived (by Morgoth) from Elves, as Tolkien postulated.

http://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Orcs

There is the further possibility that the larger, and sun-tolerant, Uruk-hai, were somehow derived by Saruman from Orcs and Men. of course, anything explicit about a sexual breeding would be an affront to Tolkien. But it isn’t necessary to assume that some perverted form of sexual activity was involved. My own hunch is that, if Tolkien had pursued the matter farther, he might have suggested something a little bit like what Dr. Moreau (in Wells’s novel) got up to. In fact, I’ve suggested that that work was an influence on Tolkien, in my article on 19th- and 20th-century literary influences on Tolkien in Drout’s J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia.

I’m not saying that these matters would or should be front and center in a continuation of The New Shadow, but I do think that, for that book to be written, Tolkien (or a fanfic writer) would probably have to pursue the matter of the origin and nature of Orcs farther than Tolkien did in the canonical writings and his letters that imparted lore to readers. (The late exploratory writings published in the History of Middle-earth probably should not be considered “canonical.”)

Dale Nelson

Fascinating. Enjoyed reading this and fantasizing about what might have been.

[…] R. R. Tolkien (Black Gate): The fragment begins in Pen-arduin, a suburb of Minas Tirith — indeed, the towers of the White […]

The New Shadow – J.R.R. Tolkien

At the beginning of the Fourth Age, after the final downfall of Sauron and after a century or more

of peace, prosperity and contentment, there seemed to be a disturbance in Men’s hearts and

minds, leading some to become restless and discontent with their lot in life and eventually

turning them to the old dark powers for answers. The Men of Gondor are not like the Elvish

peoples of old, who can live in peace and contentment for thousands of years, nor are they like

the Dwarve nation happy to live for centuries underground in their mines and tunnels. But sadly

in the Fourth Age, the Dwarves diminish and will become extinct over time and the Elves have all

left Middle-earth, emigrating over the sea to the lands of Valinor in the West. Middle-earth is

now the domain of Men, but they are a different breed and with them comes different strengths

and weaknesses with all their virtues and vices.

According to Tolkien’s own comments about “The New Shadow”, it seems that the old evil’s

influence had not gone far, even after all those years, and remembering that many of Sauron’s

supporters would have still been around generations later – brooding and plotting their revenge

with malice and spite. (It must be remembered that HERUMOR and FUINIR [Black Numenoreans

of old] were both Lords of the Haradrim from the South of Middle-earth and were devoted

followers of Sauron. They were adept of darkness and in the Fourth Age HERUMOR became the

leader of a growing cult alluded to as the DARK TREE). The old ‘evil’, it seems, lies in wait for the

most eager and corruptible minds, where revolutionary plots and satanic religions soon emerge.

It’s noted that Tolkien actually commented that the plot of “The New Shadow” was too sinister

and depressing for him to finish – maybe he thought that events in Gondor might be too similar

to the human evolution of our world. In particular, reflecting on man’s inhumanity to man – our

cruelty, injustice, wars and petty hatreds, many often conjured up by ‘dark forces’. For it is often

said that human-kind, in our world, seems to need an enemy to blame, fear and hate in order to

distract the population away from the real issues. Even if there is peace, prosperity and

contentment throughout the land, it must not flourish. Instead doubt and fear must be allowed

to fester in people’s minds.

(Echo’s of George Orwell’s 1984 seem to spring to mind here).

Back in Middle-earth, the people of Gondor soon forgot the horrors, the hard-ships and the many

deaths that had occurred, decades before, in the War against Sauron and his ‘evil’. Even

Gondorian boys are now seen playing as ‘ORCS’ – with many behaving as hooligans causing

damage. The young men of Gondor start to become bored and disillusioned with their safe and

secure lives, and some now seek new adventures and excitement, but as there is now no real

threat to their existence in Gondor, it has to be created and many now succumb to the

temptations and promises offered by the forces of the “DARK TREE”.

Of course what Tolkien really meant by stating that he felt he could not finish his new book, we

will never know. Hopefully it wasn’t for the reason offered above – but unfortunately I have this

sneaking suspicion that this might have been the reason and perhaps Tolkien didn’t like the

vision he could see of Gondor’s future and declined to explore it any further?

The book could have be a good thriller though…

Sauron may be gone, but the world is not yet mended. Morgoth’s thought still infects Arda, as it will until he bursts the Door of Night and is finally killed at the Dagor Dagorath at the end of time.

So, you know, lots of stories are possible. And the perfect way to continue at the beginning of the Age of Men, is with a political thriller, since almost all supernatural creatures have gone. Of course I’m sure there still remain at least a couple of the Nameless Things, and the paths where they gnaw the roots of the earth. Tolkien was certainly subtle enough to weave a thread of that into a political thriller tapestry. My knuckles are turning white just thinking about the possibilities.

God, I wish he’d written that book.