Telling a Clock What You Want to Eat

Long before Karel Čapek introduced the word “robot” to the general vocabulary in his 1920 play R.U.R., people had a pretty good idea of what an “automaton” or a “mechanical man” did. They learned it from popular media. Short stories, newspaper articles, vaudeville acts, comic strips, and more toyed with the idea of humanoid mechanical servants.

Or non-humanoid one. It took a very long time for the concept of “robot” to coalesce around the human form. Not until after World War II did a robot automatically conjure an image of a mechanical human, and that was largely because a word was needed to separate robots from the computer brains that increasingly took the robot’s place in media.

Before WWII, in fact, robot was frequently applied to any automatic machine which functioned with constant human supervision. Before R.U.R. mechanical man or automaton did much the same.

When a completely automated hotel was proposed, in Paris in 1913, the natural way to explain its operation was to use on these terms.

[T]o get the highest efficiency at the lowest cost … can be effected … by the “mechanical man” in the hotel – the “man” who is prompt in action, above all, and is absolutely dependable, deft, noiseless and invisible.

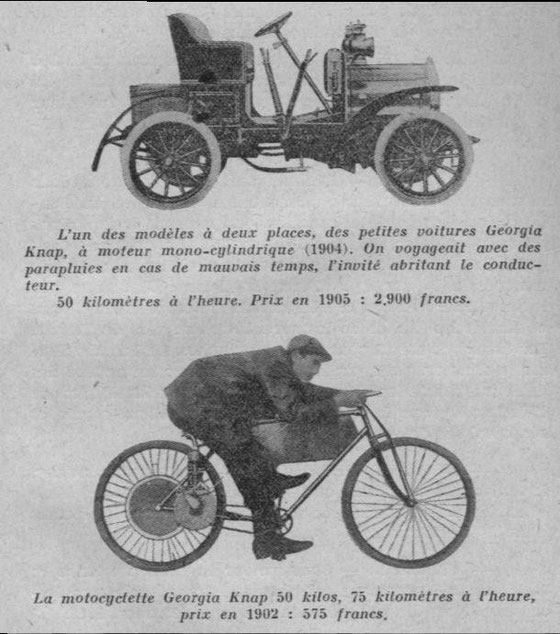

It all starts in Troyes, France, with Marie Georges Henri Knap, known as Georgi or Georgia.

Born in 1866, Knap was another of those insanely energetic and wide-ranging Victorians who made their marks in half a dozen disciplines: more in his case since he was known as “the man of 80 trades.” The first to drive an automobile in Troyes, Knap soon began manufacturing cars and motorcycles.

In 1909 he unveiled his “electric house,” his era’s equivalent of a smarthome, with pushbutton goodness at his fingertips.

M. Knaps’ villa has all the electrical appliances imaged by fiction writers to embellish the wonders of an inventor’s home, and goes the imagination one better.

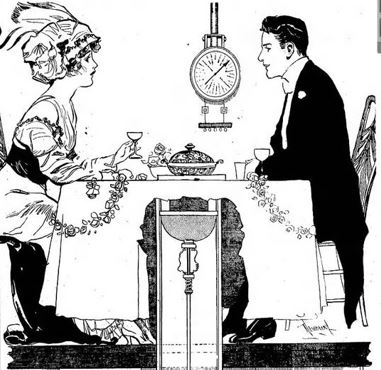

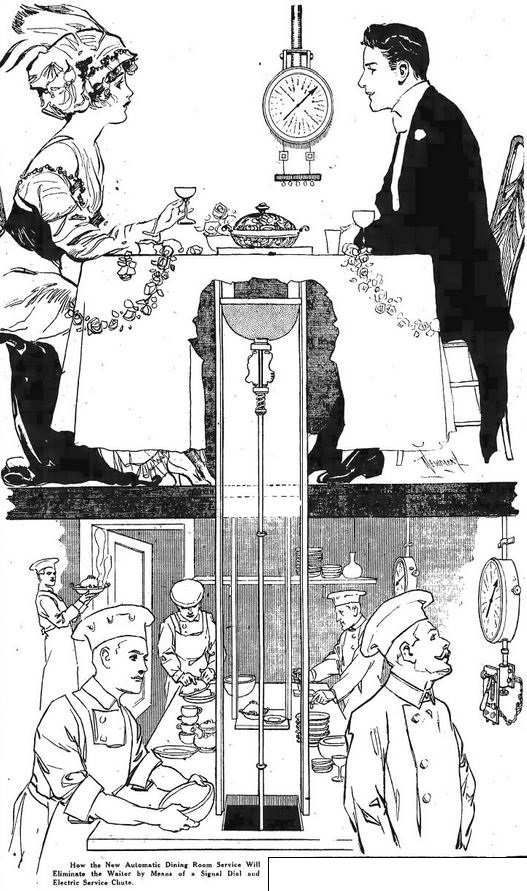

In the Feria Electra Villa, as M. Knap’s home is called, no servant ever enters the dining-room. The center of the table descends into the kitchen at the end of each course and returns with the fresh course.

The kitchen is run by electricity, which prepares the food, makes the sauces, grinds the coffee, does the cooking, and, after the meal, washes the dishes.

The outer gates of the villa open by electricity, and after the visitor has entered close by the same agency. Electric lifts take the place of dumb waiters, and in the bedroom the curtains are drawn apart and closed by electricity.

When you wish to breakfast in bed, push a button and a table, with breakfast all laid out, glides toward you.

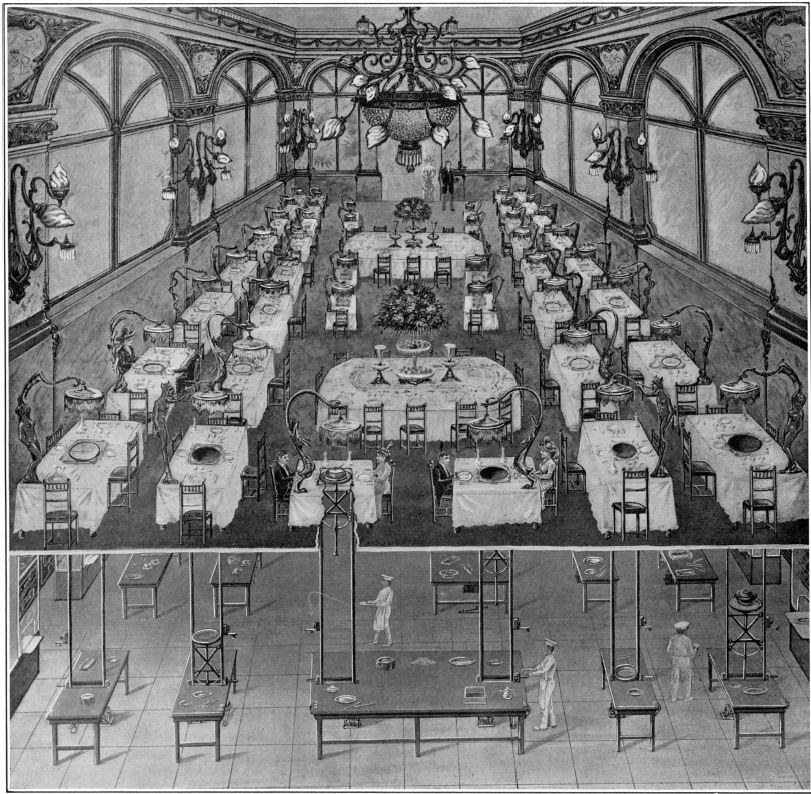

Scaling up the apparatus was the next logical course. Knap proposed to bring his inventions to a grand “Electro-Feria” hotel. Scientific American accorded his idea an entire page in its November 1, 1913 issue.

When a guest awakens in the morning his first desire is to know what time it is. Without rising he pushes a button at his bedside and immediately the time appears on a large luminous dial projected on the ceiling. … The guest, still lying in bed, calls out to the ambient air, without using a telephone: “Open the curtains and shutters. Let in the air, it is too warm. Send me a cup of coffee and my letters,” etc. … The top of a chiffonier, placed beside the bed, turns and extends itself over the bed to form a convenient table. The breakfast and the letters appear on the chiffonier, and, in less than a minute, all of your desires are satisfied, for your room is connected directly with the basement…

The restaurant is structured in the same way, with each table having a central lift which whisks your food directly from the basement below. Orders are spoken into the lampshade.

Several newspapers picked up the Scientific American report but no one ran with the idea like the editor of the Indianapolis Star Magazine, which gave it the full-page treatment on February 8, 1914. Full-page meant a lot in those days, when newspapers were more than twice the size of a magazine page.

The Electro-Feria Hotel was never built, of course, so the Star concentrated on the electro-mechanical wonders already present and in use in real-world hotels.

For instance, there is a machine that does the work of a squad of dishwashers, being absolutely careful in the handling and making breakage almost unheard of.

[T]he telautograph … transmits orders in writing, reproducing the exact chirography of the person who transmits the order or the message. … [I]t is used also in forwarding orders to distant parts of the kitchen, the waiters first giving their orders to the announcer at the entrance of the kitchen. And there is a written record from the time the order is given until the dinner bill is paid…

The housewife who prides herself on the making of deliciously smooth mayonnaise will witness with wonder and a shred of chagrin the working of the mechanism that turns out by the gallon – and a product, at that, to please the palate of the most fastidious.

The real modern hotel has thrown the book index into the rubbish heap … It has been supplanted by the monster index rack containing the names and room numbers of the guests , but different from the time-honored rack, in that it is really a card book-keeping system.

The rack is so large that the young woman who is stationed at it, equipped with the telephone and the telautograph, has to be seated on a traveling chair, in which she goes easily from one section of the rack to the other without rising.

The future rushed at dwellers in the first decades of the 20th century. No wonder they confidently expected more and greater marvels every year, a time of optimism about the future that perhaps has never been matched.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Tillie the Toiler and Rosie the Robot. His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is scheduled for a Summer release.

Fascinating. There’s a Father Brown short story circa 1911, which I’m guessing must have been inspired by Knap’s inventions? It features an inventor of automatons, (described as ‘Press a Button—A Butler who Never Drinks!’ ‘Turn a Handle—Ten Housemaids who Never Flirt!’) who is found murdered amongst his creations. These are described in some detail:

‘It opened on a long, commodious ante-room, of which the only arresting features, ordinarily speaking, were the rows of tall half-human mechanical figures that stood up on both sides like tailors’ dummies. Like tailors’ dummies they were headless; and like tailors’ dummies they had a handsome unnecessary humpiness in the shoulders, and a pigeon-breasted protuberance of chest; but barring this, they were not much more like a human figure than any automatic machine at a station that is about the human height. They had two great hooks like arms, for carrying trays; and they were painted pea-green, or vermilion, or black for convenience of distinction; in every other way they were only automatic machines and nobody would have looked twice at them.’

G.K. is suitably vague as to how these things actually work or how they get around, though.

Are you aware of Cragside House in Rothbury, Northumberland? This was built in the late Victorian period and the owner used hydro-electric power to light the building, run various machines such as a dishwasher, washing machine and a vacuum cleaner, as well as for more industrial uses such as a sawmill. Also, Arnold Bennett’s novel The Card has a description of a house which used all kinds of automation in order to keep it clean etc. to save the hero’s mother from exerting herself. I am sure that this house is based on the real one of Cragside. Neil